Literature Review

There is compelling evidence for the intergenerational effect of depression: offspring of mothers with a history of depression are at significantly greater risk for depression and other forms of psychopathology than are offspring of never-depressed mothers (

9). Studies of twin children and their parents (

25) as well as studies of children conceived through in vitro fertilization and their parents (

26) underscore the importance of environmental factors for the intergenerational transmission of depression, with evidence for the importance of depression-related effects on parenting as a mediational mechanism (

22).

The broad relation between maternal depressive symptoms and psychosocial function, including parenting, suggests a continuous effect of maternal depressive symptoms on child neurodevelopmental outcomes. This issue was examined through a systematic review of the relevant literature, based on a search of MEDLINE on Ovid (1996 to December 2017) for studies with human subjects, published in English, using the following keywords: child, child development, depression, development, maternal, maternal depression. The resulting 124 articles were scanned for evidence of the use of maternal depressive symptom scores as a continuous variable, thus allowing for analysis of effects of symptoms on child outcomes across a continuum. (The extracted articles are summarized in an annotated bibliography in the online supplement.)

The term “maternal depressive symptoms” is used in reporting the results of studies in which “depression” was quantified by scores on an inventory of depressive symptoms, and “clinical depression” is used in studies that used confirmatory diagnostic criteria. The present review, admittedly, focuses almost exclusively on maternal depression as an index for maternal mental health. There is nevertheless clear evidence for comparable effects for symptoms of maternal anxiety (

27–

29), some examples of which are cited below. The reasons for the focus on depressive symptoms are that 1) the absence of established clinical cutoffs for relevant anxiety symptom scales precludes an analysis of categorical versus continuous effects and 2) position papers in the global health community on the topic of maternal mental health focus almost exclusively on maternal depression.

A review of the relevant studies (see the

online supplement) reveals that maternal depressive symptoms operate across a continuum to influence child neurodevelopment. This conclusion is consistent with the idea that depressive disorders should be conceptualized as a “fluid continuum” rather than as discrete syndromes (

30). This point is further underscored by recent findings on the effects of “positive maternal mental health” on parenting and child socioemotional and cognitive development.

Research Findings

There is intergenerational transmission of the risk for depression from parents, especially the mother, to offspring (

9,

31). Imaging studies focusing on neural systems implicated in affective disorders reveal significant differences between the offspring of mothers with and without a history of clinical depression. The unaffected adolescent offspring of mothers clinically diagnosed with major depressive disorder differ from offspring of mothers without mental disorders on measures of hippocampal volume (

32), the neural circuitry associated with reward processing (

33), amygdala volume (

34), and cortical thickness (

35). Children whose mothers showed persistently high levels of postnatal depressive symptoms, comparable to those exhibited during chronic mild depression, show amygdala enlargement (

35), typical of individuals at risk for mood disorders.

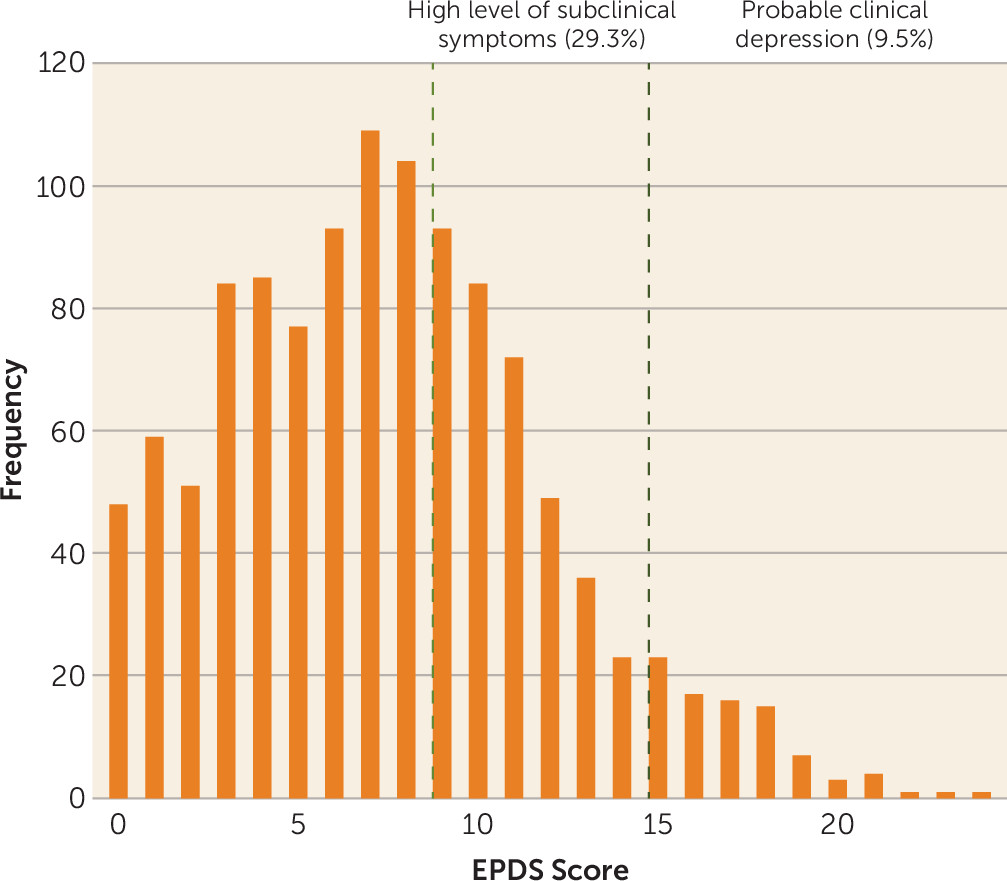

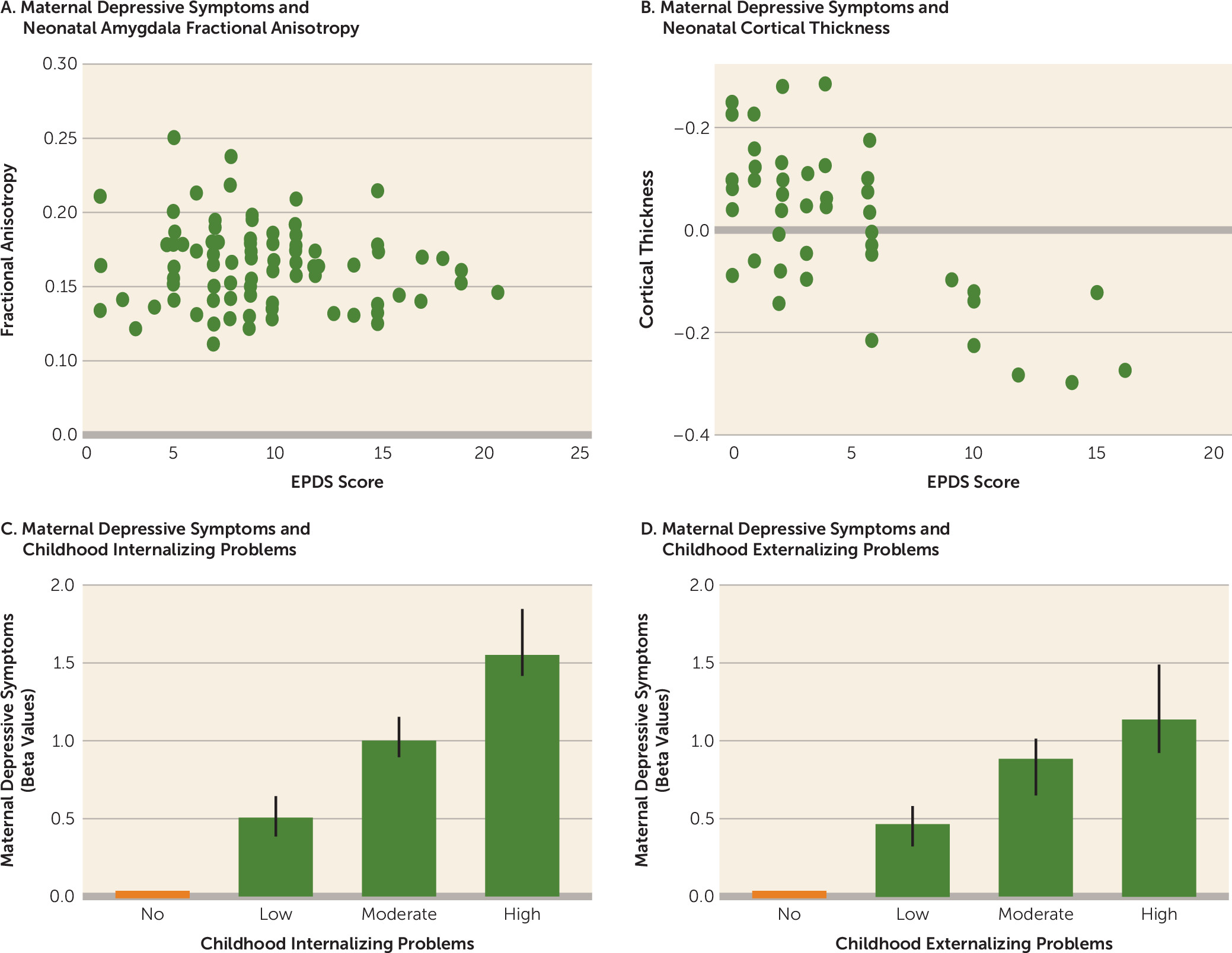

More recent studies reveal that the maternal influence on the neurodevelopment of the offspring is not limited to instances where maternal depressive symptoms exceed clinical thresholds. These studies examined neural development as a function of maternal depressive symptoms across the continuum. The reports (see the

online supplement) emerge from a number of community-based samples using number of depressive symptoms as a continuous variable. For example, in the Growing Up in Singapore Towards Healthy Outcomes (GUSTO) cohort, brain structure and connectivity were assessed as a function of antenatal maternal depressive symptoms using the EPDS. Validated cutoffs for probable depression on the EPDS (

13) are symptom scores of 13 or more for the postpartum period and 15 or more for the antenatal period, with the latter adjusted for overlap between specific symptoms and the normal conditions of pregnancy, such as sleep or appetite. The mean number of antenatal depressive symptoms on the EPDS scale in the GUSTO study was 7.5 (SD=4.5), with only 9.5% of women with scores above the antenatal EPDS cutoff (

Figure 1). Nevertheless, in studies in which offspring underwent imaging shortly after birth, the number of antenatal depressive symptoms was associated with alterations in amygdala microstructure at birth, as determined using diffusion tensor imaging (

36) (

Figure 2A) as well as at 6 months of age with functional connectivity of the amygdala with a range of prefrontal regions, including the insula (

39,

40). Individual differences in amygdala structure at birth predicted later behavioral problems, as did differences in the insular cortex (

40,

41). The association of prenatal maternal depressive symptoms with amygdala structure persisted through to 4.5 years of age.

The association between maternal depressive symptoms and fetal neurodevelopment in the GUSTO cohort was observed across the normal range of antenatal depressive symptoms. This same finding was apparent in a study with a U.S. sample (

42) in which depressive symptoms were evaluated using the CES-D scale, with a clinical cutoff score of 16. The mean CES-D score in the sample was well below the cutoff score (mean=6.0; SD=4.1; see

Figure 2 in reference

42 for associations of cortical thickness across CES-D scores) and revealed significant cortical thinning in children, primarily in the right frontal lobe, that was associated with the number of antenatal maternal depressive symptoms used as a continuous variable. The strongest association was with maternal symptoms at 25 weeks of gestation, with cortical thinning in 19% of the whole cortex and 24% of the frontal lobes, primarily in the right superior medial orbital and frontal pole regions of the prefrontal cortex. The significant association between prenatal maternal depressive symptoms and subsequent child externalizing behavior was mediated by cortical thinning in prefrontal areas of the right hemisphere. Likewise, in a Canadian sample, Lebel et al. (

37) (

Figure 2B) found that antenatal EPDS scores were negatively correlated with offspring cortical thickness in right inferior frontal and middle temporal regions, an association that survived correction for postpartum EPDS scores. Postpartum EPDS scores were negatively correlated with offspring right superior frontal cortical thickness and with diffusivity in white matter originating from that region after correcting for prenatal EPDS scores. The mean EPDS score for the mothers in the study was 4.7 (SD=4.2) (for the second trimester, when the greatest effect was observed), and the association was apparent across the full range of depressive symptoms. The importance of these findings is underscored by studies revealing reduced cortical thickness as a risk factor for depression (

35), suggesting that the intergenerational transmission of the neurodevelopmental risk for depression in offspring is not unique to clinical cases of maternal depression. The same conclusion emerges from the GUSTO study findings (

39–

41) of altered right amygdala-insula connectivity, which is strongly associated with anxiety disorders (

43). In sum, these findings reveal a continuous relation between the quality of maternal mental health and fetal neurodevelopment: the higher the number of maternal depressive symptoms, the greater the neuroanatomical evidence for vulnerability in the offspring.

The association between maternal depressive symptoms and those of adolescent offspring shows a continuous relation across the range of maternal symptoms (

44). The same pattern emerges from studies examining the influence of maternal mental health on measures of child behavioral problems. Studies of community samples commonly include mothers with a wide range of variation in self-reported symptoms of depression or anxiety. In contrast, clinical studies examine the offspring of mothers with verified disorders compared with control subjects without disorders. An extensive meta-analysis (

6) of the relation between maternal depressive symptoms and child behavioral problems revealed that for internalizing problems, the associations were somewhat stronger in clinical studies, where depression was clinically diagnosed, than in community studies relying on self-reported symptoms. In contrast, there was no such difference between clinical and community studies in effect size for externalizing problems. Likewise, effect sizes were no different between diagnosed depression and self-reported symptoms with measures of child psychopathology.

A number of community-based studies reveal significant associations between maternal mood and child behavioral problems using depressive symptom measures as a continuous rather than a categorical variable (e.g.,

45,

46; see also the

online supplement). The significant associations observed in these studies imply an effect that cuts across the population. This issue was systematically explored in a detailed analysis of the trajectories of depressive symptoms in a large community sample of mothers and children in Rotterdam, the Netherlands (Generation R) (

38). Only 34% of mothers showed no evidence of depressive symptoms over the perinatal period, revealing a distribution comparable to that observed in the GUSTO cohort (see

Figure 1). The authors report evidence for a graded increase in the frequency of child behavioral problems in association with the level of maternal depressive symptoms, with a significant increase apparent even between the offspring of mothers with low levels of depressive symptoms compared with offspring of mothers with no symptoms (

Figure 2C,D). Likewise, an analysis of data from the National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Study of Early Child Care and Youth Development (

47) showed that a continuous measure of maternal depressive symptoms in infancy predicted cognitive function in early primary school. Depressive symptoms were assessed with the CES-D (using a cutoff score of 16); the mean score for the sample was 9.2 (SD=7.2), with ∼15% of the mothers scoring above the cutoff. Self-reported levels of maternal depressive symptoms across the normal range also predicted the developmental change that occurred in emotion regulation: children of mothers reporting fewer symptoms showed improved emotion regulation between ages 4 and 7 years, an effect that was especially pronounced among children with greater physiological reactivity (

48). Similarly, antenatal maternal depressive symptoms across the normal range predicted negative emotional reactivity among infants (

49). Finally, Goodman et al. (

50) examined depressive symptoms in a cohort of mothers at high risk for depression in relation to infant neurodevelopment, using the Brazelton scales. Depressive symptom scores were significantly associated with social interaction, state organization, autonomic system, and irritability scales; however, there was no significant difference between infants whose mothers met diagnostic criteria for depression and those whose mothers had high levels of depressive symptoms but did not meet diagnostic criteria. Comparable findings emerged from the Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children, which examined cognitive abilities and found that maternal depressive symptoms were negatively associated with IQ (

51).

The graded effects of maternal depressive symptoms are consistent with extensive studies revealing that self-reported level of maternal distress in nonclinical samples is associated with measures of fetal physiology, including fetal cardiovascular function (see reference

4 for a review). Likewise, in a population-based sample, personality traits of mothers associated with increased depressive symptoms, including anger, impulsivity, detachment, and suspicion, predicted increased symptoms of depression and anxiety in the young adult offspring (

52). These studies provide compelling evidence for the importance of maternal depressive symptoms across the continuum for child health and development.