The 12-month and lifetime prevalence rates of bipolar I disorder according to DSM-5 criteria (

1) are currently 1.5% and 2.1%, respectively, in the United States (

2). Bipolar I disorder is associated with elevated functional disability (

3,

4), mortality (

5), and suicide risk (

6). The majority of individuals with bipolar I disorder present with a depressive episode as the index episode, and depressive symptoms and episodes dominate the longitudinal course of the illness (

3,

7–

9). Notably, the rates of disability, morbidity, and suicide (

10,

11) associated with bipolar I disorder are further increased during depressive episodes.

Several effective and approved pharmacologic agents are available for treating bipolar I mania (

12–

14), but there are fewer evidence-based approved treatment options for bipolar I depression. Conventional antidepressants are commonly prescribed in the treatment of bipolar I depression, but they have demonstrated limited efficacy in clinical trials (

15) and may increase the risk of mood destabilization (e.g., induction of episodes of hypomania, mania, or mixed states) when used on a long-term basis (

16,

17). Currently, treatments approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for acute bipolar I depression include the atypical antipsychotics quetiapine (monotherapy) (

18), lurasidone (monotherapy or adjunctive with lithium or valproate) (

19), and olanzapine (combination treatment with fluoxetine) (

20).

Cariprazine, a dopamine D

3 receptor–preferring D

3/D

2 and serotonin 5-HT

1A receptor partial agonist (

21,

22), is an atypical antipsychotic approved for the treatment of schizophrenia and manic or mixed episodes associated with bipolar I disorder in adults (

23). Cariprazine exhibits high affinity for and occupancy of both D

3 and D

2 receptors. D

3 receptors are highly expressed in brain regions involved in cognitive function, motivation, and reward-related behavior (

24), providing the basis for the hypothesis that pharmacologic engagement of D

3 receptors by cariprazine may have a positive effect on cognition (

25), mood, and/or measures of reward, including reduction of anhedonia (

26–

28). In preclinical studies, cariprazine exhibited antidepressant and procognitive-like effects in rodent models (

28,

29), outcomes that were partially mediated by the D

3 receptor (

29). Other receptor interactions are also implicated in cariprazine’s antidepressant effects, notably 5-HT

1A agonism (

30).

Methods

This phase 3 study was conducted from March 2016 to July 2017. Participants were screened and recruited in compliance with the International Conference on Harmonization Good Clinical Practice Guideline and the Declaration of Helsinki from 41 study centers in the United States and 31 centers in Europe (16 in Bulgaria, three in Estonia, four in Lithuania, and eight in Poland). The study was approved by institutional review boards for U.S. sites or ethics committees and government agencies for European sites. Participants provided written informed consent after receiving a complete description of the study and before initiation of study participation.

Study Design

This was a 6-week randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled, parallel-group, fixed-dose study in adult patients with bipolar I depression. A 1- to 2-week screening/washout period was followed by a 6-week double-blind treatment period and a 1-week safety follow-up with no study medication. An interactive voice/web response system was used to randomize treatment assignment (using computer-generated numbers), monitor enrollment, and allocate investigational product using a code matching the assigned medication. All patients and study staff were blind to treatment allocation throughout the study duration. The randomization ratio was 1:1:1 for placebo, cariprazine 1.5 mg/day, or cariprazine 3.0 mg/day, and all oral capsules were identical in appearance and taken at approximately the same time each day (morning or evening). All participants who were assigned to treatment with cariprazine began on 1.5 mg/day, and those assigned to the 3.0 mg/day group were increased to that dosage on day 15. Drug holidays of up to 3 consecutive days were allowed if tolerability issues occurred for the allocated fixed dosage, but participants were discontinued if a drug holiday lasted ≥4 consecutive days.

Participants

Participants were outpatients 18–65 years of age who met DSM-5 criteria for bipolar I disorder with a current major depressive episode of ≥4 weeks and <12 months, without psychotic features in the current episode, as confirmed by the Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview. Participants were also required to have a score ≥20 on the 17-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (HAM-D) (

32), a score ≥2 on item 1 of the HAM-D, and a score ≥4 on the Clinical Global Impressions severity subscale (CGI-S) (

33). Physical examination, clinical laboratory, and ECG results were normal or judged by investigators not to be clinically significant, and pregnancy was excluded in women with childbearing potential with negative serum beta-human chorionic gonadotropin testing. Participants were excluded if they had a score >12 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (

34), four or more episodes of mood disturbance (depression, mania, mixed, or hypomania) within the previous 12 months, or any current psychiatric diagnosis besides bipolar I disorder or specific phobias (including personality disorders of significant enough severity to interfere with the study, as judged by the principal investigator). Participants were excluded if they had a substance use disorder (including alcohol) within the previous 6 months, suicide risk or risk of injury to self or others, a history of nonresponse in the current depressive episode to two or more antidepressant trials of adequate dosage, or treatment failure in the current depressive episode of quetiapine, lurasidone, or combination treatment with olanzapine and fluoxetine. Exclusionary concurrent medical conditions included those with the potential to interfere with study participation, confound interpretation of results, or endanger the well-being of the participant. Psychotropic drug use was prohibited except for eszopiclone, zolpidem, zopiclone, chloral hydrate, and zaleplon (for insomnia); lorazepam or equivalent benzodiazepine at a maximum dosage of 2.0 mg/day if the dosage had been stable for a month prior to screening, or rescue doses of lorazepam or equivalent benzodiazepine (for agitation/restlessness/hostility; maximum dosage, 2.0 mg/day for a maximum of 3 consecutive days); and rescue doses of diphenhydramine or benztropine (for extrapyramidal symptoms) or propranolol (for akathisia that emerged or worsened during the study).

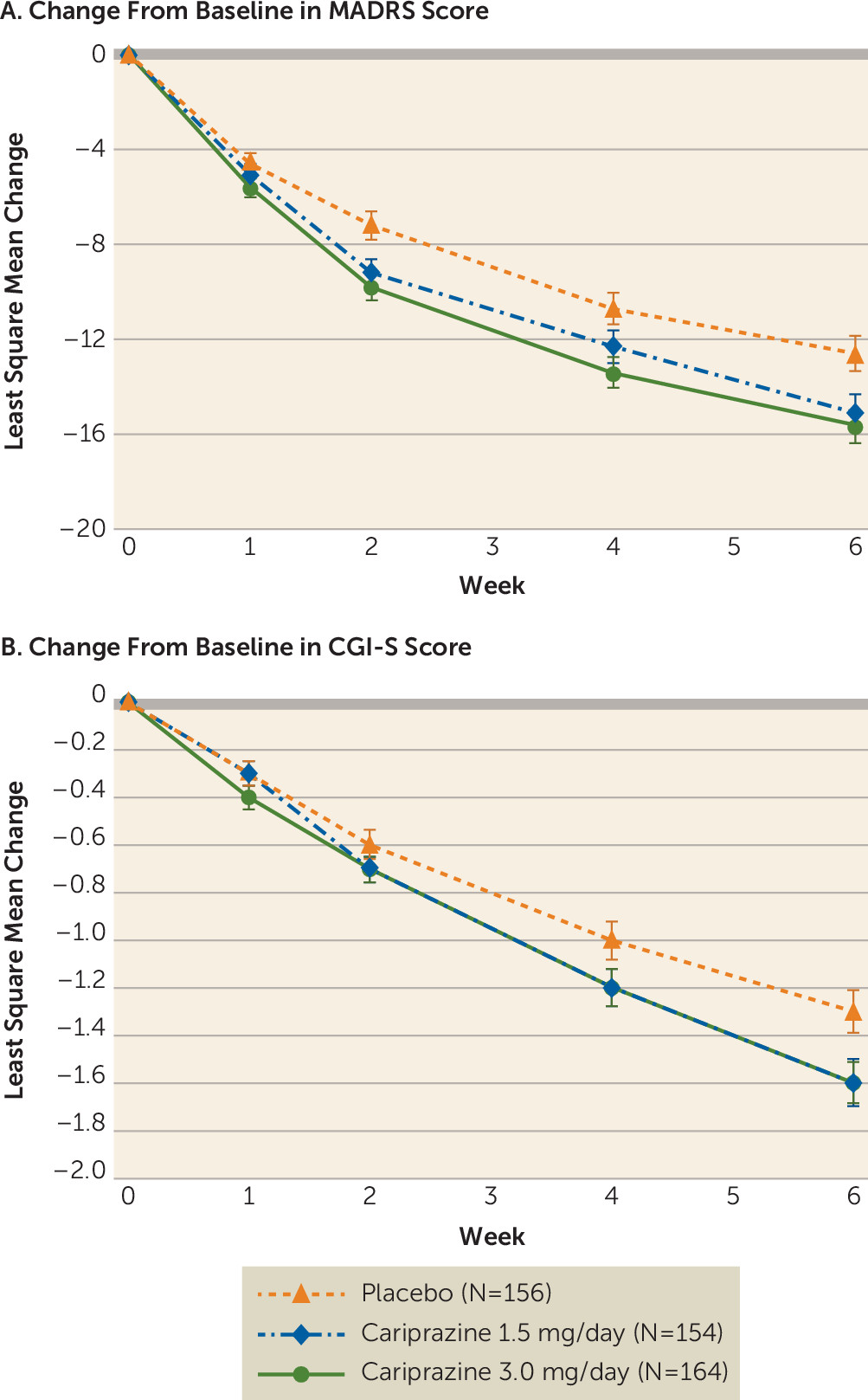

Efficacy Parameters

The primary efficacy parameter was change in score from baseline to week 6 in Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

35). The secondary efficacy parameter was change from baseline to week 6 in CGI-S score. Additional efficacy parameters included changes from baseline to week 6 in scores on the HAM-D, the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A) (

36), and the 16-item Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology–Self-Report (QIDS-SR) (

37), as well as rates of MADRS response (a ≥50% reduction from baseline score), MADRS remission (a score ≤10), and HAM-D remission (a score ≤7) at week 6. The MADRS and the CGI-S were administered at each study visit (including at screening, at baseline [randomization], and at weeks 1, 2, 4, and 6 [double-blind treatment period]), and the remaining efficacy assessments were administered at screening, baseline, and at least one double-blind visit.

Safety

Physical examination, ECG, and clinical laboratory monitoring were conducted at screening and at the end of week 6. Vital signs were recorded at every visit. Height was recorded at screening. The YMRS was administered at screening, baseline, and weeks 4 and 6. Extrapyramidal symptom scales (e.g., the Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale [

38], the Abnormal Involuntary Movement Scale [

33], and the Simpson-Angus Rating Scale [

39]) were administered at baseline and at each double-blind study visit. The Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (

40) was administered and adverse event monitoring was conducted at every visit.

Statistical Analysis

Efficacy assessments were based on the intent-to-treat population, which consisted of all randomized participants who took at least one dose of investigational product and had at least one postbaseline MADRS measurement. Safety assessments were based on the safety population (randomized patients who took at least one dose of investigational product). Changes in MADRS score from baseline to week 6 were analyzed by a mixed-effects model for repeated measures (MMRM) with treatment group, study center, visit, and treatment group-by-visit interaction as fixed effects and the baseline MADRS score and baseline score-by-visit interaction as covariates. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to model the covariance of within-patient scores, and the Kenward-Roger approximation was used to estimate denominator degrees of freedom. Sensitivity analyses were performed using a pattern-mixture model based on non-future-dependent missing value restrictions (

41) to assess the robustness of primary MMRM results. Analyses of changes from baseline in CGI-S score and QIDS-SR score were conducted with an MMRM similar to the primary efficacy analysis model.

By-visit changes from baseline were analyzed by an analysis of covariance model with last observation carried forward imputed for MADRS, CGI-S, HAM-A, QIDS-SR, and HAM-D scores, with treatment group and study center as factors and baseline value as covariate. MADRS response and remission and HAM-D remission rates with last-observation-carried-forward imputation were reported by treatment group and by visit and were analyzed by logistic model with fixed factors of treatment group and baseline score. For efficacy analyses with study center as a factor, centers with fewer than two participants (intent-to-treat population) in any treatment group were pooled to form pseudo-centers containing at least two participants in each treatment group. All statistical analyses were performed using SAS, version 9.3 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.).

The sample size was determined with an assumed effect size of 0.36; 160 participants per treatment group would have a 90% and 88% power to detect that at least one cariprazine dose was statistically significant in improving the primary and secondary efficacy endpoint, respectively, compared with placebo (with multiplicity adjustment). Adjustments for multiple comparisons were made using the matched parallel gatekeeping procedure (

42) to control the overall type I error rate (alpha=0.05). Statistical hypothesis tests for all efficacy measures were performed at a significance threshold of 5% (two-sided), and all confidence intervals were two-sided 95%. The secondary efficacy parameter could be considered statistically significant only if the primary efficacy parameter was significant (p<0.05).

Safety parameters included treatment-emergent adverse events; abnormal clinical laboratory results, ECG results, or vital signs as well as suicide risk (based on Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale score) (descriptive statistics were computed for each); mania (a YMRS score ≥16); and extrapyramidal symptom events (treatment-emergent parkinsonism: Simpson-Angus Rating Scale score ≤3 at baseline and >3 after baseline; treatment-emergent akathisia: Barnes Akathisia Rating Scale score ≤2 at baseline and >2 after baseline).

Results

Patient Disposition

Of 782 participants screened, 488 were randomly assigned to double-blind treatment with placebo (N=163), cariprazine 1.5 mg/day (N=160), or cariprazine 3.0 mg/day (N=165) (see Figure S1 in the online supplement). Completion rates were similar between groups: 85.4%, 85.4%, and 81.2%, respectively, for the three groups. Most premature discontinuations of the combined population were due to adverse events (4.2%), loss to follow-up (3.8%), and withdrawal of consent (3.5%). Premature discontinuations due to adverse events occurred in 2.5% of participants in the placebo group, 4.5% in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, and 5.5% in the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group. Adverse events that led to discontinuations for each treatment group were as follows: in the placebo group, headache (N=2, 1.3%), hypomania (N=1, 0.6%), and vertigo (N=1, 0.6%); in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, akathisia (N=3, 1.9%) and N=1 (0.6%) each for nausea, diarrhea, increased heart rate, pruritus, and sedation; and in the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group, N=1 (0.6%) each for akathisia, bipolar disorder (sites were encouraged to report worsening of the underlying condition if there was a change in severity or frequency that was deemed clinically significant by the principal investigator and did not follow the pattern expected for the disease), disturbance in attention, dizziness, insomnia, lethargy, malaise, musculoskeletal stiffness, nausea, restlessness, and suicidal ideation.

Baseline demographic characteristics, clinical history (

Table 1), and MADRS and HAM-D scores (

Table 2) were generally comparable among groups.

Primary Efficacy Parameter

Both cariprazine dosages were significantly associated with reduced depressive symptoms compared with placebo. For the primary efficacy parameter—change from baseline in MADRS score at week 6—the least squares mean difference was −2.5 (95% CI=−4.6, −0.4; adjusted p=0.033) for the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group and −3.0 (95% CI=−5.1, −0.9; adjusted p=0.010) for the 3.0 mg/day group compared with placebo (

Table 2). The effect sizes were 0.28 and 0.34 for the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day and 3.0 mg/day groups, respectively. The greater MADRS improvements compared with placebo were statistically significant at weeks 2 and 6 for the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, and at all visits between weeks 2–6 for the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group (

Figure 1).

Secondary and Additional Efficacy Parameters

CGI-S scores from baseline to week 6 improved in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group relative to the placebo group, but the difference fell short of significance (least squares mean difference=−0.2, 95% CI=−0.5, −0.0; p=0.071). Similarly, CGI-S scores improved in the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group compared with the placebo group, but the difference was not significant when adjusted for multiplicity (least squares mean difference=−0.3, 95% CI=−0.5, 0.0; adjusted p=0.066). The CGI-S score effect sizes for the cariprazine 1.5 and 3.0 mg/day groups were 0.18 and 0.29, respectively. Additional efficacy parameters are summarized in

Table 2.

HAM-A scores improved significantly from baseline to week 6 in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group compared with the placebo group (least squares mean difference=−1.6, 95% CI=−2.9, −0.3; p=0.014), but the improvement in the 3.0 mg/day group did not reach statistical significance (least squares mean difference=−1.1, 95% CI=−2.4, 0.2; p=0.112). QIDS-SR scores from baseline to week 6 improved in both cariprazine dosage groups relative to the placebo group, but the differences were not significant.

MADRS response rates at week 6 were significantly greater in the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group (51.8%, p=0.024, number needed to treat [NNT]=8.3), but the rate differences did not reach significance for the 1.5 mg/day group (48.1%, p=0.130, NNT=12.0) compared with the placebo group (39.7%) (

Table 2). MADRS remission rates at week 6 were significantly higher in both the cariprazine 1.5 and 3.0 mg/day groups (33.1%, p=0.037, NNT=10.0, and 32.3%, p=0.039, NNT=10.8, respectively) compared with the placebo group (23.1%). HAM-D remission rates were significantly greater in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group (p=0.036), but not in the 3.0 mg/day group, compared with the placebo group.

Safety

Adverse events.

Adverse events are summarized in

Table 3. Common treatment-emergent adverse events (those occurring in ≥5% of either cariprazine treatment group and twice the rate of the placebo group) were nausea, akathisia, dizziness, and sedation. The majority of treatment-emergent adverse events were mild or moderate in intensity (96.7% of those in the placebo group, 94.6% of those in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, and 95.8% of those in the 3.0 mg/day group). Serious adverse events occurred in two participants in each treatment group, and none were considered by the investigator to be treatment related. One patient died of suicide in the screening phase, prior to randomization or exposure to study medication. No deaths occurred among randomized participants in any group throughout the study. Rescue medication (alprazolam, clonazepam, lorazepam) use was reported in nine patients in the placebo group, nine in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, and 12 in the 3.0 mg/day group.

Rates of treatment-emergent extrapyramidal symptom events are presented in Table S1 in the online supplement; the most commonly reported were restlessness and akathisia. Restlessness was reported in six patients in the placebo group (3.8%), two in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group (1.3%), and 12 in the 3.0 mg/day group (7.3%), and akathisia was reported in five patients in the placebo group (3.2%), 10 in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group (6.4%), and nine in the 3.0 mg/day group (5.5%). When restlessness and akathisia were excluded, rates of treatment-emergent extrapyramidal symptom events were generally low: <5% of the placebo, cariprazine 1.5 mg/day, and cariprazine 3.0 mg/day participants.

In the double-blind period, suicidal ideation occurred in 8.2%, 10.8%, and 7.9% of the placebo, cariprazine 1.5 mg/day, and cariprazine 3.0 mg/day groups, respectively. No suicidal behavior was reported.

Clinical parameters.

Changes in laboratory and clinical parameters were generally comparable among treatment groups, and differences between groups were not clinically relevant (

Table 4). The mean weight change at week 6 was −0.27 kg for the placebo group, 0.48 kg for the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, and 0.45 kg for the 3.0 mg/day group. Weight increases ≥7% of body weight occurred in three participants in the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group and none in the placebo or cariprazine 1.5 mg/day groups. The proportions of patients in both cariprazine dosage groups with treatment-emergent significant changes in cholesterol, glucose, and triglyceride levels were generally similar to those in the placebo group (see Table S2 in the

online supplement). No evidence of transaminase alteration that comports with Hy’s law was recorded. Treatment-emergent mania occurred in 1.3% of the placebo participants, 0.7% of the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day participants, and none of the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day participants.

Extent of exposure.

The mean treatment duration was 39.3 days (SD=8.7) for the placebo group, 38.6 days (SD=9.1) for the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group, and 38.5 days (SD=9.0) for the 3.0 mg/day group.

Discussion

The results of this phase 3 study demonstrate that cariprazine is effective in treating acute bipolar I depression, as indicated by significantly greater improvements in depressive symptoms on the primary efficacy measure (MADRS score) compared with placebo. The efficacy was observed for both fixed dosages of cariprazine assessed in this study (1.5 mg/day and 3.0 mg/day). These findings are consistent with the results of a previously reported, similarly designed phase 2 study (

31), thus replicating the antidepressant effects of cariprazine in the treatment of bipolar I depression. The cariprazine-treated groups exhibited 2.5- and 3-point greater reductions in MADRS score compared with the placebo group, a magnitude of improvement similar to that reported with other atypical antipsychotics approved for the treatment of bipolar I depression (

8,

31,

43–

50). Additionally, the rate of MADRS response was significantly higher compared with the placebo group in the cariprazine 3.0 mg/day group but not in the 1.5 mg/day group, but the rates (48% and 52%) were comparable to those reported for other FDA-approved treatments in nonactive comparator trials for bipolar depression: 58%−65% for quetiapine (

43,

46); 52% for lurasidone (

44); and 39%−56% for olanzapine (as monotherapy and combined with fluoxetine) (

48,

49). A possible explanation for lack of significance in MADRS response for the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day group compared with the placebo group may be the relatively high placebo response rate (39.7%) compared with the aforementioned studies (30%−43%) (

43,

44,

46,

48,

49). MADRS remission rates were significantly higher for both cariprazine dosage groups compared with the placebo group.

The improvement in CGI-S score from baseline to week 6 was 1.6 points for both cariprazine groups, which was consistent with the 1.1- to 2.2-point improvement reported in published trials of atypical antipsychotics for treatment of bipolar I depression (

8,

31,

43,

45–

50). Neither cariprazine dosage group experienced significantly reduced CGI-S scores compared with the placebo group, which contrasts with the phase 2b study results, in which cariprazine 1.5 mg/day was significantly associated with improved CGI-S scores compared with placebo. The CGI-S score least squares mean differences in this study were −0.2 and −0.3 for cariprazine 1.5 mg/day and 3.0 mg/day, respectively, and the previous study reported least squares mean difference values of −0.4 and −0.3 for these dosages (

31). The lack of CGI-S score change significance in the present study may be due to the higher placebo response observed (placebo group CGI-S score change, −1.3) compared with the previous study (−1.0).

Mean weight increases were relatively low (less than 0.5 kg) for both cariprazine groups, and rates of participants who experienced weight gain ≥7% of their body weight were also low. Mean changes in metabolic parameters and shifts into abnormal ranges were small and not thought to be clinically relevant. The absence of clinically relevant changes in metabolic parameters is of high significance in this population because individuals with bipolar I disorder and individuals treated with atypical antipsychotics have an increased risk of diabetes, cardiovascular disease, metabolic disorders, and clinical overweight or obesity (

51). The proportions of patients in both cariprazine dosage groups with clinically relevant shifts in glucose and lipid levels were generally similar to the placebo group. These findings are important because weight gain and metabolic disruption can lead to reduced adherence to atypical antipsychotic treatment in patients with bipolar I depression (

52), and obesity in individuals with bipolar disorder is associated with substantially worse cognitive ability, independent of symptom severity (

53).

The risk of treatment-emergent manic or hypomanic switch and mood destabilization is a concern associated with commonly used treatments for bipolar I depression, such as antidepressant medications. In this study, the occurrence of treatment-emergent mania was low in both cariprazine groups, and rates were similar to that of the placebo group, suggesting that cariprazine is not associated with mood destabilization or manic switching in patients with bipolar I disorder. Given the efficacy and FDA approval for treating manic and mixed episodes of bipolar I disorder with cariprazine, the lack of manic switch risk in a previous study (

31) and in the present study (the occurrence of treatment-emergent mania did not increase in the cariprazine-treated patients during the study, and mean MADRS scores decreased), and no evidence of depressive switch risk in previous studies of cariprazine for mania (

54–

56), cariprazine demonstrates efficacy in treating both manic and depressive phases without causing mood destabilization.

Common adverse events were similar to those observed in previous trials of atypical antipsychotics for bipolar I depression. Akathisia occurred in 6.4% and 5.5% of patients in the cariprazine 1.5 mg/day and 3.0 mg/day groups, respectively. These rates were comparable to those reported in other atypical antipsychotic bipolar I depression trials: 5.0%−9.8% for quetiapine at 300 mg/day and 600 mg/day (

43,

45,

50), 7.9% for lurasidone at 20–60 mg/day, and 10.8% for lurasidone at 80–120 mg/day. The rates of akathisia in this study were lower than those observed in cariprazine bipolar I mania trials (∼19%−22%) (

55,

56), which is believed to be related to the lower dosages used for treatment of depressive episodes (1.5–3.0 mg/day) compared with manic episodes (3.0–12.0 mg/day) and a slower titration method used in the bipolar depression trials compared with the mania trials; patients in the present trial were given 1.5 mg/day for 2 weeks before any dosage escalations. Cariprazine was generally well tolerated, and this study had greater rates of completion (81%−85%) than many other atypical antipsychotic bipolar I depression studies, which have reported completion rates in the range of 48%−80% (

8,

31,

43–

49). The high completion rates are particularly compelling given the outpatient status of the participants. The greater rates of completion may be attributable to the more gradual titration method used in this study, in which participants in the 3.0 mg/day group reached that dosage on day 15, compared with on day 1 in a cariprazine bipolar I mania phase 3 pivotal trial (

54), which may have led to increased tolerability. Reasons for discontinuation rates >3% in either cariprazine group included adverse events, loss to follow-up, and withdrawal of consent.

In comparison to cariprazine use in bipolar mania (approved dosage range, 3.0–6.0 mg/day), the slower titration and lower dosage used in the bipolar depression program appear to result in an improved tolerability profile. For example, rates of extrapyramidal symptoms and akathisia in the approved dosage range of 3.0–6.0 mg/day for mania were 26% and 20%, respectively, whereas rates of extrapyramidal symptoms and akathisia were 4.3% and 6.4%, respectively, for the 1.5 mg/day dosage and 4.2% and 5.5%, respectively, for the 3.0 mg/day dosage.

Limitations of the study include lack of an active comparator, short treatment duration, and an inability to assess cariprazine efficacy and tolerability at dosages other than 1.5 mg/day and 3.0 mg/day. The exclusion of participants with suicidality prevented the assessment of this subpopulation of patients with bipolar I disorder, who have an elevated risk of suicide (

6,

57). Participants with other comorbid psychiatric conditions or bipolar II disorder were also excluded, preventing the generalizability of the results to these populations.

In conclusion, the efficacy and safety results of this study are generally consistent with those of the previously reported phase 2 trial (

31) and a second phase 3 trial (NCT02670538) of similar design that was completed recently (the results of which are to be published separately). In the present study, both 1.5 mg/day and 3.0 mg/day of cariprazine met the primary efficacy endpoint compared with placebo, and CGI-S scores were lower compared with placebo. Cariprazine at both dosages also had favorable tolerability profiles, low discontinuation rates, and non–clinically significant metabolic changes and weight gain.