Reducing Suicidal Ideation Through Insomnia Treatment (REST-IT): A Randomized Clinical Trial

Abstract

Objective:

Methods:

Results:

Conclusions:

Methods

Participants

Randomized Assignment and Masking

Clinical Measurements

Secondary Outcome Variables

Sleep metrics.

Depression severity.

Hopelessness.

Health-related quality of life.

Overall status and treatment response.

Antidepressant treatment resistance.

Adverse events.

Actigraphy.

Statistical Analyses

Results

Baseline

| Characteristic | Controlled-Release Zolpidem (N=51) | Placebo (N=52) | Overall (N=103) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Age (years) | 39.7 | 14.5 | 41.2 | 12.0 | 40.5 | 13.2 |

| Body mass index | 28.3 | 6.4 | 28.2 | 5.6 | 28.2 | 6.0 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Female | 32 | 63 | 32 | 62 | 64 | 62 |

| Clinic | ||||||

| 1 | 23 | 45 | 27 | 52 | 50 | 49 |

| 2 | 15 | 29 | 15 | 29 | 30 | 29 |

| 3 | 13 | 25 | 10 | 19 | 23 | 22 |

| Race or ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 30 | 59 | 33 | 63 | 63 | 61 |

| African American | 12 | 24 | 16 | 31 | 28 | 27 |

| Hispanic | 4 | 8 | 1 | 2 | 5 | 5 |

| Other | 5 | 10 | 2 | 4 | 7 | 7 |

| Antidepressant trials in current episode | ||||||

| Zero | 29 | 57 | 30 | 58 | 59 | 57 |

| One | 14 | 27 | 12 | 23 | 26 | 25 |

| Two or more | 8 | 16 | 10 | 19 | 18 | 17 |

| Lifetime suicide attempt(s) | 15 | 29 | 16 | 31 | 31 | 30 |

| Posttraumatic stress disorder | 13 | 25 | 16 | 31 | 29 | 28 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 2 | 4 | 3 | 6 | 5 | 5 |

| Generalized anxiety disorder | 20 | 39 | 21 | 41 | 41 | 40 |

| Panic disorder with agoraphobia | 9 | 18 | 8 | 15 | 17 | 17 |

| Panic disorder without agoraphobia | 10 | 20 | 7 | 14 | 17 | 17 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Scale for Suicide Ideation: suicide ideation score | 12.2 | 5.3 | 11.8 | 5.3 | 12.0 | 5.3 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| Scale for Suicide Ideation: suicide attempts | ||||||

| Never | 36 | 71 | 36 | 69 | 72 | 70 |

| Once | 8 | 16 | 8 | 15 | 16 | 16 |

| Two or more times | 7 | 14 | 8 | 15 | 15 | 15 |

| Scale for Suicide Ideation: death wish | ||||||

| No suicide attempt | 36 | 71 | 36 | 69 | 72 | 70 |

| Low | 3 | 6 | 3 | 6 | 6 | 6 |

| Moderate | 6 | 12 | 4 | 8 | 10 | 10 |

| High | 6 | 12 | 9 | 17 | 15 | 15 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) past-week ideation intensity | 1.71 | 1.03 | 1.58 | 1.02 | 1.64 | 1.02 |

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| C-SSRS: a lot of difficulty or inability to control thoughts | 6 | 12 | 12 | 23 | 18 | 18 |

| C-SSRS: deterrents probably or definitely stopped suicide attempt | 43 | 86 | 35 | 67 | 78 | 76 |

| Clinical Global Impressions Scale, severity scale | ||||||

| Mildly ill | 3 | 6 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Moderately ill | 33 | 65 | 32 | 62 | 65 | 63 |

| Markedly ill | 13 | 25 | 18 | 35 | 31 | 30 |

| Severely ill | 2 | 4 | 2 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Mean | SD | Mean | SD | Mean | SD | |

| Hamilton Depression Rating Scale score | 28.7 | 4.7 | 29.6 | 7.0 | 29.1 | 5.9 |

| Insomnia Severity Index score | 20.7 | 4.0 | 21.0 | 4.3 | 20.9 | 4.1 |

| Beck Hopelessness Scale score | 13.4 | 4.8 | 12.7 | 4.6 | 13.1 | 4.7 |

| Disturbing Dream and Nightmare Severity Index score | 10.5 | 8.8 | 10.2 | 7.7 | 10.3 | 8.2 |

| Dysfunctional Beliefs and Attitudes About Sleep Scale score | 6.7 | 1.6 | 6.7 | 1.5 | 6.7 | 1.6 |

| Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale 32, daily living and role functioning score | 2.4 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.6 |

| Behavior and Symptom Identification Scale 32, relationship to self and others score | 2.5 | 0.6 | 2.2 | 0.7 | 2.3 | 0.7 |

| Mini-Mental State Examination score | 29.6 | 0.8 | 29.3 | 1.0 | 29.4 | 0.9 |

| Epworth Sleepiness Scale score | 7.9 | 5.0 | 8.5 | 4.7 | 8.2 | 4.9 |

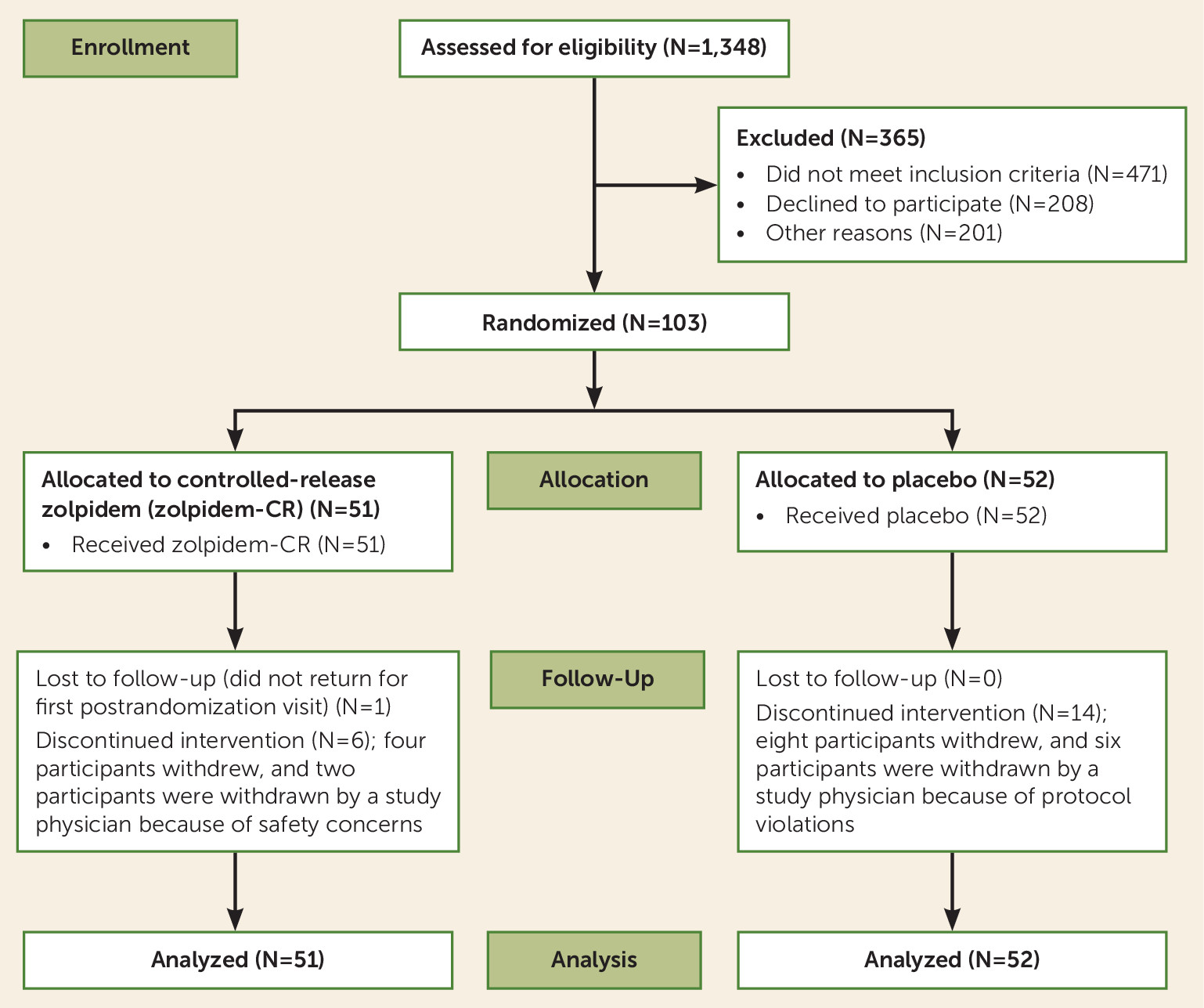

Randomized Treatment

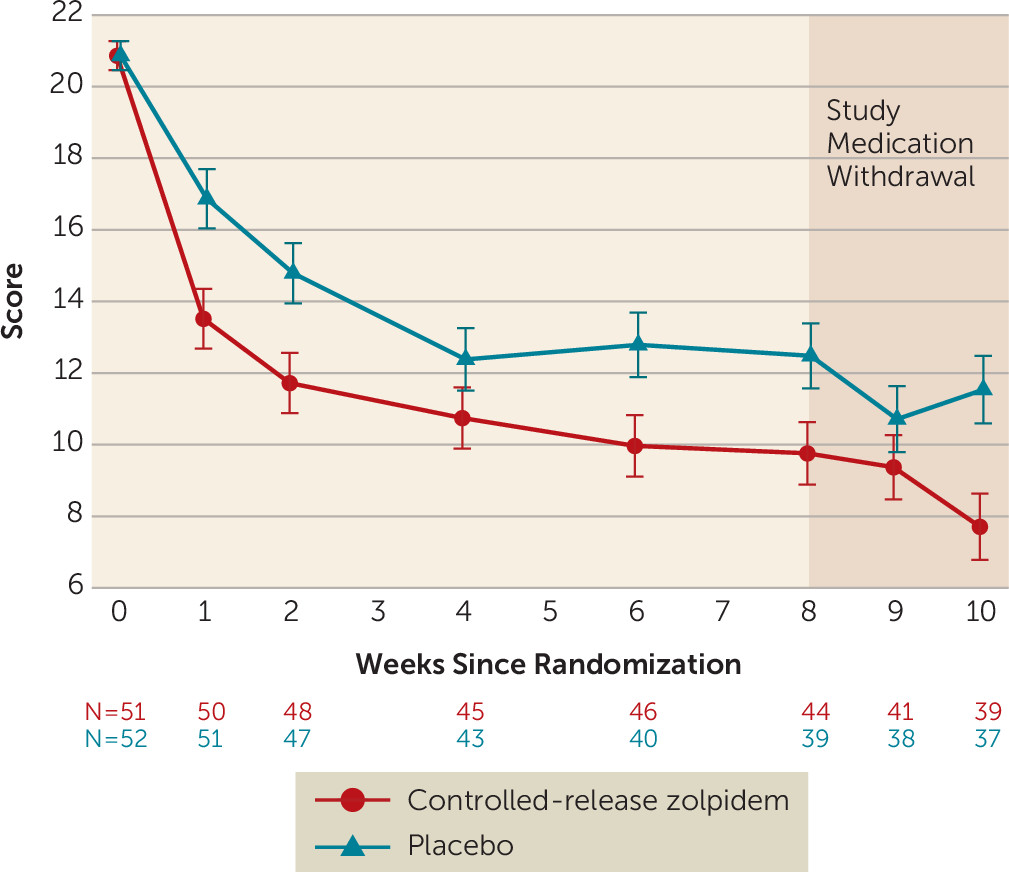

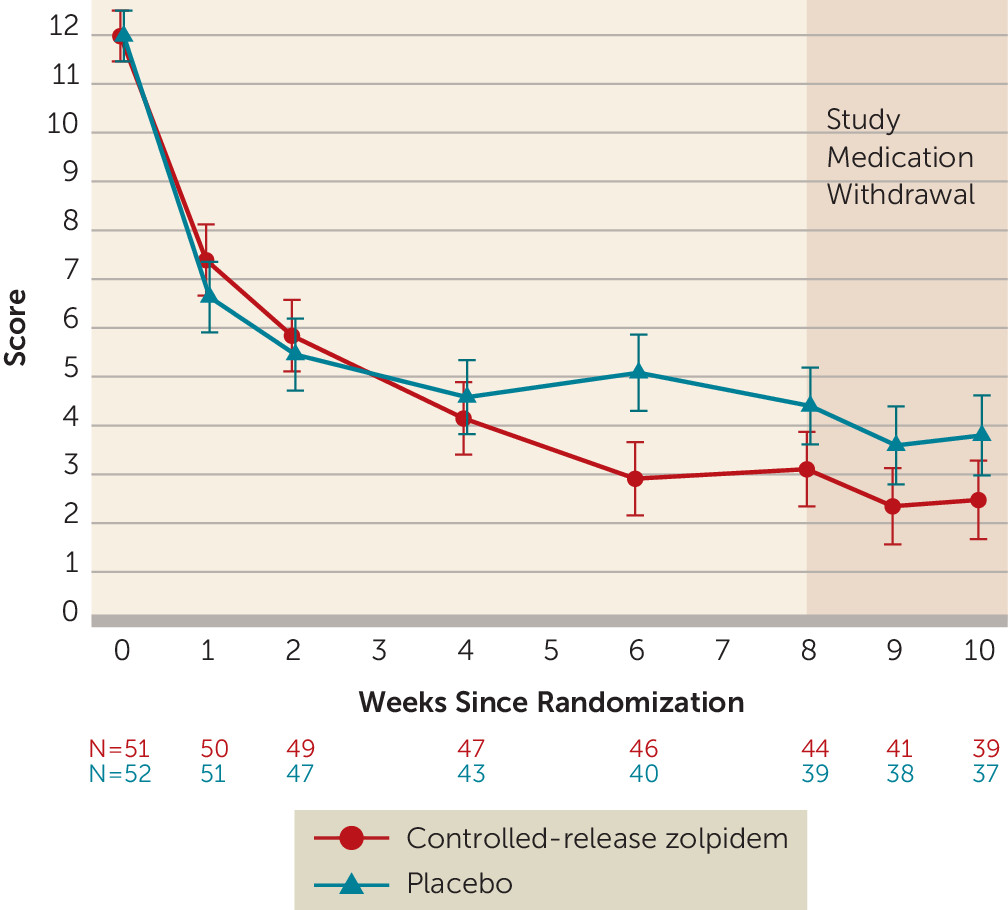

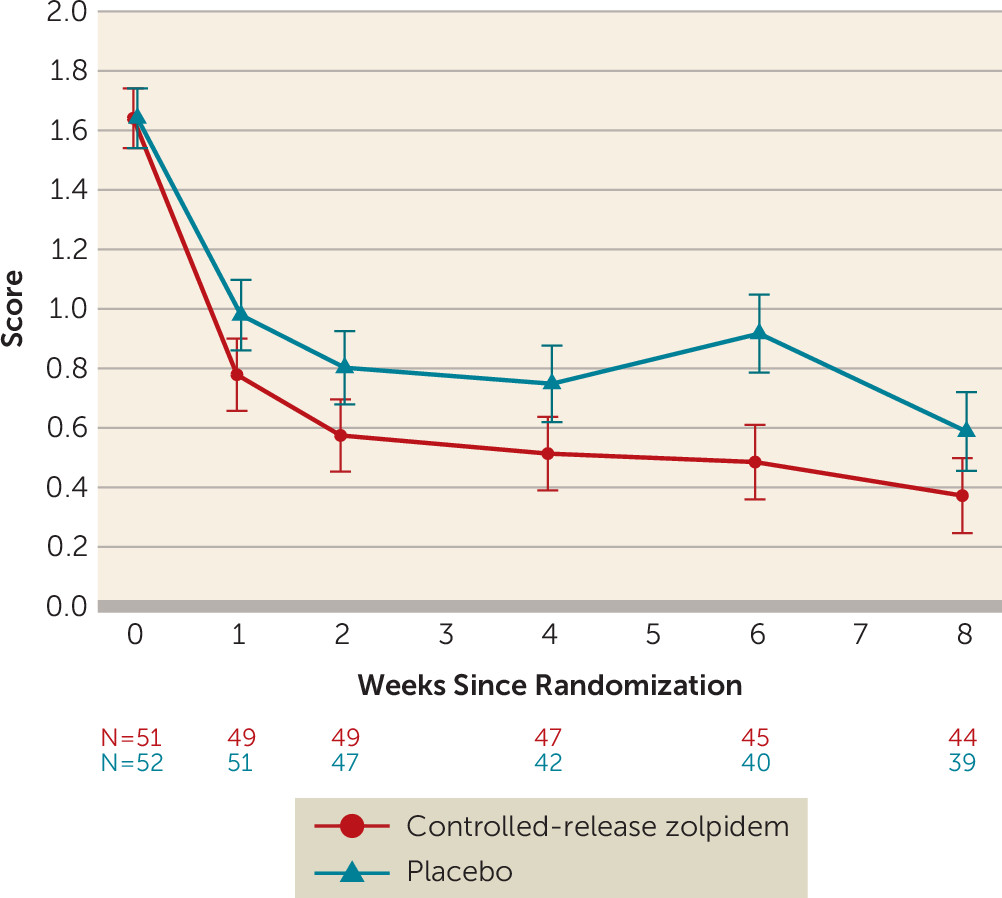

Outcomes

Follow-Up

Adverse Events

Discussion

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

Footnote

Supplementary Material

- View/Download

- 46.15 KB

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Keywords

Authors

Competing Interests

Funding Information

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

Export Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).