Suicide is a major public health concern, accounting for over 47,000 deaths in the United States in 2017 (

1), and representing the 18th leading cause of death worldwide in 2016 (

2). Risk is multifactorial, attributable to genetic liability (

3–

7), environmental stressors (

8–

12), and comorbid conditions, including alcohol use disorder (AUD) (

13–

16). AUD itself is relatively common, is associated with an array of other psychiatric outcomes (

17), and carries a substantial economic burden (

18). It is also associated with increased mortality (

19–

22): alcohol consumption accounted for over 5% of deaths worldwide in 2016 (

23).

In this study, we used data from Swedish population registries to address two primary research questions. First, we tested whether AUD and death by suicide are associated, before and after accounting for psychiatric comorbidity. Second, we assessed whether the observed association is attributable to confounding familial factors, potentially causal processes, or a combination of mechanisms, through the use of co-relative control models.

Results

The selected birth cohort consisted of 2,229,880 individuals.

Table 1 presents the frequency of suicide, AUD, and other covariates. Among women, the suicide rate for those without AUD was 0.29% (N=3,062), and among those with AUD, it was 3.54% (N=1,158). The corresponding rates among men were 0.76% (N=8,079) and 3.94% (N=3,229), respectively. The mean age at AUD registration was 39.99 years (SD=11.70) for women and 39.38 years (SD=11.47) for men. Mean age at suicide death was 36.22 years (SD=11.35) for women and 35.83 years (SD=11.01) for men. Correlations (r) among non-AUD psychiatric diagnoses ranged from 0.42 to 0.87 (see Table S1 in the

online supplement), with the strongest estimates between psychotic disorders and AUD or drug abuse.

Population-Based Analyses

In preliminary Cox regressions in which AUD was the sole predictor and was time-varying, AUD and suicide were strongly associated in both women (hazard ratio=37.53, 95% CI=34.82, 40.45) and men (hazard ratio=16.33, 95% CI=15.60, 17.08). Adjusting for sociodemographic covariates did not substantially alter the effect of AUD (women: hazard ratio=37.10, 95% CI=34.26, 40.18; men: hazard ratio=16.18, 95% CI=15.42, 16.96).

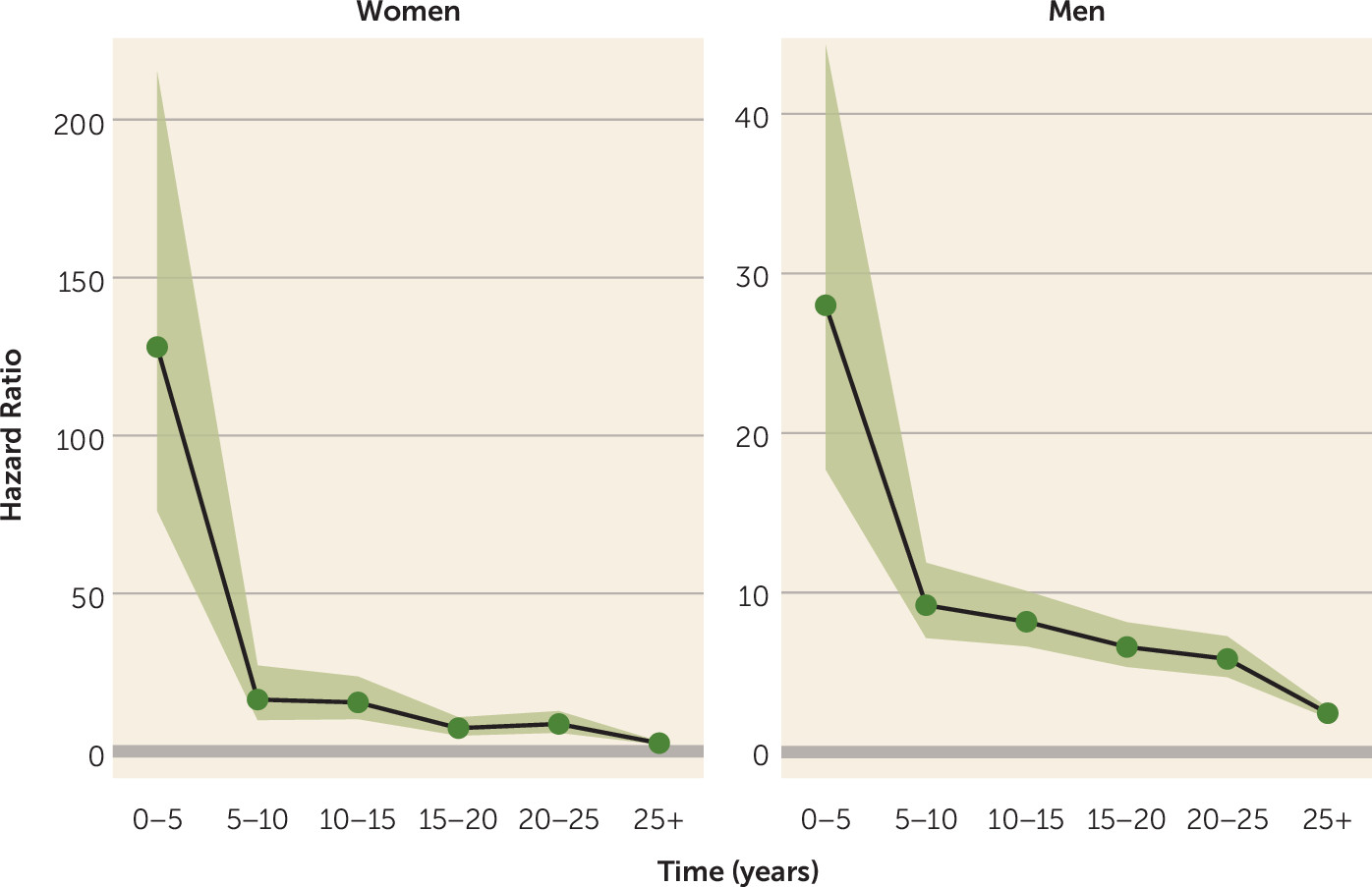

We tested the proportionality assumption by estimating the hazard ratio for AUD, adjusted only for sociodemographic covariates, across individuals for whom the length of observation time differed in 5-year increments. The impact of AUD onset for risk of suicide declined rapidly over time (see Table S2 in the online supplement). We therefore constructed a full model, adjusted for both sociodemographic and time-varying psychiatric covariates, allowing for different hazard ratios across observation periods.

In these full models, AUD was the strongest predictor of suicide death in the first 5 years of observation for both sexes (

Table 2). Hazard ratios declined precipitously between the first and second 5-year increments, declining more gradually thereafter (

Figure 1). The risk associated with AUD remained comparable to, and sometimes exceeded (although with overlapping confidence intervals), risks associated with psychotic and affective disorders. After 25 years of observation, AUD remained significantly associated with suicide for both women (hazard ratio=2.62, 95% CI=2.16, 3.14) and men (hazard ratio=2.44, 95% CI=2.15, 2.79).

Because of concerns about data sparseness, and because of the relatively modest changes in risk associated with AUD beyond the first 5 years after a registration, secondary analyses estimated hazard ratios averaged across observation time. We tested the association between AUD and suicide among individuals without a registration for other psychiatric diagnoses (944,378 women, 7,701 with AUD; 1,002,880 men, 23,823 with AUD), including sociodemographic covariates, and AUD as a time-varying predictor. The associations were strong, with hazard ratios of 73.74 (95% CI=63.68, 85.37) for women and 20.69 (95% CI=19.07, 22.46) for men.

We then tested whether age at onset of AUD was associated with suicide risk. In a Cox proportional hazards model accounting for birth year, parental education, and time-dependent psychiatric comorbidity, we estimated the effect of age at AUD onset, binning into 10-year increments beginning with <25 years of age. We observed steady decreases in risk, relative to an age at onset <25, for ages 25–35 and in each subsequent age bin (see Table S3 in the online supplement).

Co-Relative Analyses

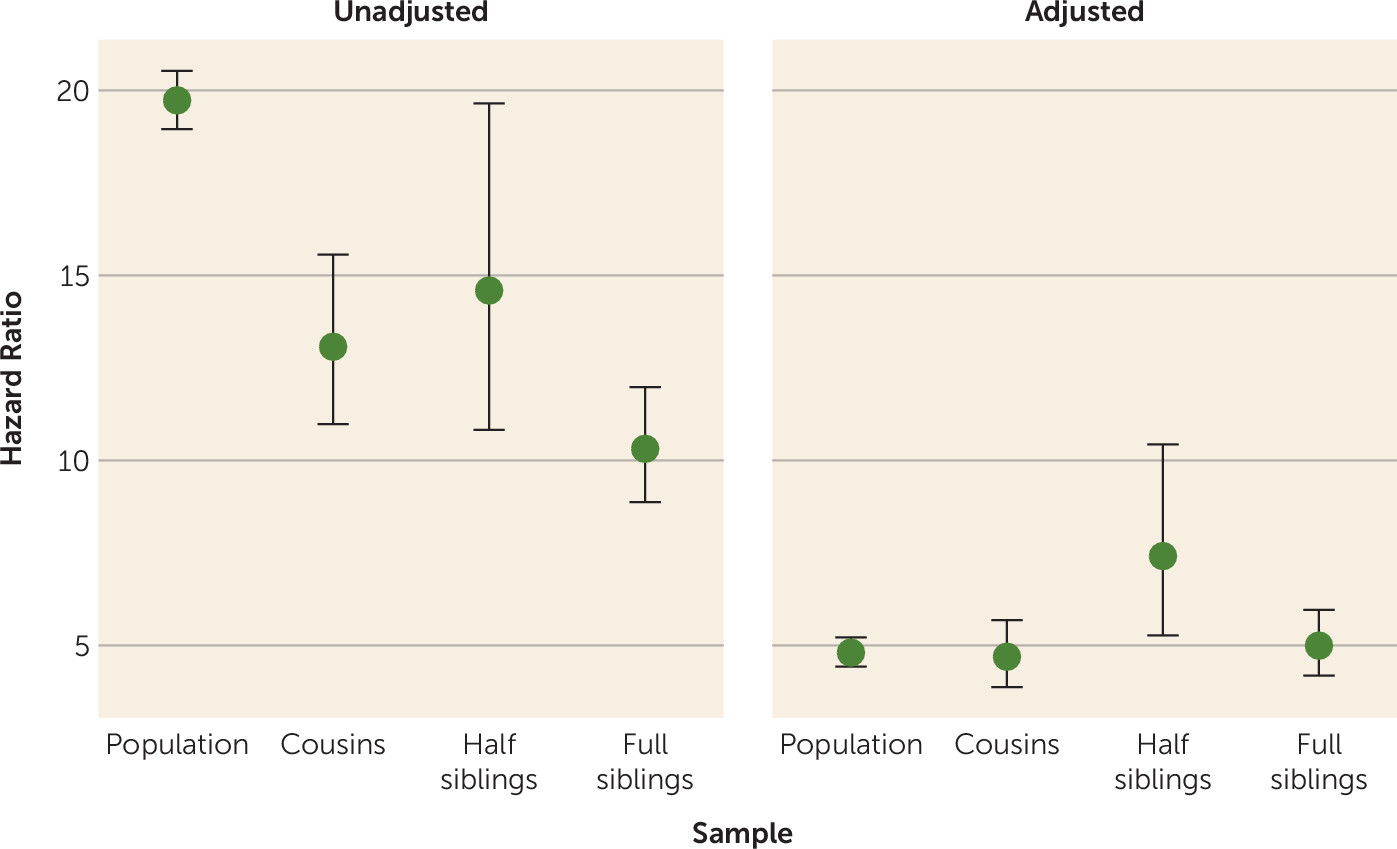

We next ran parallel models within data sets consisting of same-sex relative pairs of varying levels of genetic resemblance—cousins, half siblings, and full siblings. The results are depicted in

Figure 2 and

Table 3. In unadjusted models, as the degree of genetic relatedness increased, the magnitude of the AUD-suicide association decreased, although half siblings deviated from this trend, suggesting that familial confounding contributes to the observed association between AUD and death by suicide. In models adjusted for time-dependent psychiatric comorbidity, a markedly different pattern was observed. The estimates were consistent across groups of varying relatedness, suggesting little or no additional familial confounding of the association between AUD and suicide. Half siblings were again outliers, although estimates are known imprecisely; confidence intervals overlapped with all estimates except that from the population-based adjusted model. In a supplemental model in which the hazard ratio for monozygotic twins could be extrapolated, the hazard ratio declined further but remained significantly greater than 1 (hazard ratio=3.69, 95% CI=2.77, 4.90; see the supplemental text and Table S4 in the

online supplement).

Discussion

For Swedish individuals born between 1950 and 1970, AUD was associated with a substantially increased risk of death by suicide. In models accounting for psychiatric comorbidity and shifts in risk across observation time, hazard ratios for AUD were 128 for women and 28 for men in the first 5 years after a registration. While risks associated with AUD were substantially attenuated beyond that time frame, they remained elevated (hazard ratio>2 for both sexes) even 25 or more years later. These findings are comparable to those of previous studies of AUD and suicide in Denmark and the United States (

16,

31) and with a recent meta-analysis that included samples of diverse national origins (

32). They are similarly in line with Swedish studies examining the increased suicide risk associated with eating disorders (

33) and obsessive-compulsive disorder (

28). We observed a markedly higher initial risk among women, although this difference was reduced in adjusted models. Critically, co-relative analyses indicated a complex etiology underlying the AUD-suicide association: Familial factors that increase risk for both AUD and death by suicide, in conjunction with a pronounced and potentially causal pathway, likely contribute to the observed association.

This is, to our knowledge, the largest population-based study examining the association between alcohol use disorder and death by suicide, accounting for psychiatric comorbidity, and further clarifying the potential familial confounding of the observed association. Previous studies in Scandinavian countries have explored complementary research questions, reporting evidence of familial aggregation of AUD and suicide (

34) and comparable magnitudes and patterns of association (

31,

35). In the context of the extant research, the present findings provide insight into the potential consequences of AUD on a broad scale.

The effect of AUD was substantially higher among women in unadjusted models, although this discrepancy was attenuated in adjusted models, suggesting that psychiatric comorbidity differentially affects AUD-based risk across the sexes. This may reflect the higher threshold for AUD among women and the higher prevalence of internalizing disorders. Women die by suicide at lower rates than men overall (

36); however, data regarding the relationships among AUD, suicide, and sex are relatively scarce, and many studies have been insufficiently powered to directly examine the AUD-suicide association in women given their lower prevalence of both outcomes. This likely contributes to inconsistent findings. Some studies have reported that women have higher alcohol-related risks of suicidal behavior (

14,

15), while others have not detected moderation by sex (

37). Our findings indicate that psychiatric comorbidity attenuates the AUD-suicide association, particularly among women. Inclusion of these factors in analytic and theoretical models is thus critical in order to accurately estimate risks specific to AUD.

In this study, hazard ratios were even more pronounced among individuals with AUD who did not have registrations for other psychiatric conditions. In those without a registration for other psychopathology, a group that constituted the majority (87.3%) of the full sample but only 27.5% of those with AUD, the very large increase in suicide risk associated with AUD makes these individuals an obvious focus for interventions in what might mistakenly be considered a low-risk group.

The co-relative models demonstrate two key findings. First, familial confounders account for a substantial proportion of the association between AUD and suicide. As increasing degrees of familial factors are accounted for across co-relative pairs, the association between AUD and suicide declines in the unadjusted models. This suggests that AUD is indexing a variety of dispositional features that influence risk of both AUD and suicide. Second, even after adjusting for psychiatric comorbidity, a likely source of the familial confounding described above, there remains a substantial risk of suicide following an AUD registration. The relative stability in hazard ratio estimates across relative pairs (

Figure 2, adjusted panel) indicates that this residual association is consistent with a causal mechanism (

26). Thus, the pronounced associations observed in the preliminary model unadjusted for psychiatric comorbidity and averaged across observation time, where we observed 16- to 37-fold increased risk, may in part be due to an array of correlated factors indexed by AUD (e.g., propensity toward impulsiveness, genetic loading for mental illness, etc.) and to a causal effect of AUD. The latter may take the form of stressful circumstances or events attributable to the disorder (

9,

10,

38), substance-induced depression (

39,

40), social isolation (

41), acute intoxication (

14), or other factors, many of which we are unable to address using registry-based data. Overall, our findings are consistent with previous evidence of familial confounding in related outcomes, such as drug abuse and mortality (

42) and AUD and mortality (

22).

We note an elevated suicide risk among half siblings discordant for AUD (or timing of death by suicide), which deviates from the otherwise consistent hazard ratios across co-relative pairs. Relative to full sibling and cousin pairs, members of these pairs have more often been exposed to parental marital disruption, and rates of externalizing psychopathology are substantially higher in their parents (

43,

44). The rate of suicide is higher among half siblings in this sample (1.2% for men, 0.52% for women). There are likely to be confounders relevant to risk among half siblings that are not relevant, or are less relevant, to other co-relative pairs. Although identifying those factors would be speculative using only registry data, previous evidence suggests that children of divorced parents are at increased risk for depression recurrence (

45), smoking (

46), suicidal behavior (

47), and alcohol misuse (

48), as well as measures of social functioning such as lower educational achievement (

49) and adult socioeconomic status (

50).

The violation of the proportionality assumption highlights the dynamic nature of suicide risk and indicates that it decreases as time elapses from the first AUD registration. In addition, this finding supports the assertion that AUD causally affects risk: If the observed AUD-suicide association were merely attributable to stable confounding factors (e.g., personality, genetic liability to psychiatric disorders), we would not expect to observe such a marked dissipation of risk over time. While the goal of testing this model was to provide context for our primary findings, these results raise the possibility that the time frame shortly after AUD registration may represent a critical period during which risk of suicide is most pronounced. A previous study of suicide risk in the wake of a nonfatal self-harm incident provides further support for this possibility (

51). Another possibility is that the observed association of declining risk over time is due in part to individuals whose AUD remits after their initial registration, among whom risk of suicide may then diminish.

In addition, we observed that earlier onset of AUD—which is posited to be an indicator of severity, propensity toward externalizing behavior (

52,

53), and genetic liability (

54–

56)—is associated with increased suicide risk. The implications of these findings are twofold. First, prevention and intervention efforts may be most effective when directed toward individuals facing a relatively recent AUD-related incident. Second, these efforts may be especially fruitful for those with early onset of AUD. Further studies aimed at dissecting the time-sensitive nature of risk are essential.

Our findings must be considered in the context of our use of registry data. AUD registration corresponds to a high threshold for AUD, as it requires that an individual come to the attention of the medical or criminal justice system. Some individuals who meet diagnostic criteria will escape detection. Therefore, conservatively, the present findings should be considered most relevant to severe AUD. The mean age at first AUD registration is somewhat older than mean onset ages reported in studies that do not rely on registry data and is in part a function of cohort selection: As earlier cohorts are observed later into life, they present more opportunities for late-stage AUD-related registrations (e.g., those derived from alcohol-related medical conditions) to be identified. Our previous study of Swedish adoptees, which included those born as late as 1993, found a mean onset age of 33.9 years for AUD (38.2 years among women, 32.3 years among men) (

27). Given that the mean age at death by suicide precedes the mean age at first AUD registration in the present cohort, it is possible that some suicide decedents suffered from as-yet-unrecognized AUD. Such a misclassification error could lead to an underestimation of the risks associated with AUD. Despite these drawbacks, the registry-based approach we used here is objective and not subject to self-report bias; furthermore, a high degree of correspondence among AUD registration sources (odds ratios, 9.6–74.8 [

27]) indicates that the measure is valid.

There are several notable limitations to this study. First, the start date of data availability differs across registries. We made every effort to select a cohort to maximize coverage; however, data will be consistently available across all registries for younger cohorts, and as these cohorts age into risk periods for AUD and suicide, our ability to further elucidate the mechanisms underlying observed associations will improve. Our use of registries also reduces our ability to identify less severe cases of AUD; relatedly, we may miss episodes of relapse that are not recorded in registers but that contribute to suicide risk years after the initial AUD diagnosis as individuals proceed through remissions and relapses. Second, exclusion of deaths of undetermined intent reduced the adjusted effect of AUD (see Table S5 in the

online supplement); this may be due to difficulties determining whether alcohol-related deaths were intentional, particularly given the relationship between alcohol misuse and impulsive behavior (

12,

57–

59).

While co-relative analyses account for a range of potential familial confounders, including genetic liability shared by AUD and suicide, they do not account for individual-level environmental factors that may jointly influence risk of both AUD and suicide. Such influences may contribute to increased risks attributed to AUD in co-relative models, leading to an overestimation of AUD’s putatively causal effect.

Finally, the findings may not be generalizable to other populations: Native-born Swedes may represent a more homogeneous culture than exists in more ethnically diverse countries such as the United States. However, as a robust association between AUD and suicidal behavior has been observed in the United States (

16), any discrepancies may be quantitative rather than qualitative.

This study represents a well-powered analysis of the relationship between AUD and suicide, which is of substantial public health relevance. We present evidence, using complementary population-based, longitudinal, and co-relative analytic designs, that is consistent with the hypothesis that a substantial component of the association between AUD and suicide risk is potentially due to a causal mechanism, even after accounting for psychiatric comorbidity. Notably, this relationship is more prominent among women, among individuals with a recent AUD registration, and among those with an earlier onset of AUD. Our results have potential clinical relevance, as they indicate that AUD, even outside the context of psychiatric comorbidity, is a potent risk factor for suicide. While this association is strongest during the period close to an AUD registration, the effect persists for decades. Women, among whom death by suicide is less common overall, exhibit AUD-related risk comparable to men. These findings underscore the nuanced role of AUD in suicide risk and have implications for efforts aimed at reducing suicide and characterizing risk potential as a function of coexisting conditions.