As DEI leaders at major academic psychiatry programs across the United States, we recognize the importance of these positions and advocate for increased support for our activities. Diversity improves productivity, supports recruitment and retention, fosters enhanced innovation, and promotes a more inclusive workforce climate (

1). International protests centering on the Black Lives Matter movement—triggered by the recent murders of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd, underscored by a COVID-19 pandemic with racial inequities in morbidity and mortality—have resulted in an urgent need for psychiatry departments to reexamine and commit to fully supporting these leadership positions.

Unfortunately, the case of Dr. A is not unique. DEI leadership roles are typically held by women and/or Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC) with limited resources, such as lack of salary support, discretionary funds, and administrative backing (

2,

3). As our nation publicly confronts the ongoing trauma of systemic racism, academic institutions are being called to critically evaluate and interface with racism in new ways. DEI leaders are being summoned for one-on-one and programmatic consultation, antiracist curriculum development, antibias training, and skill acquisition. However, many of these institutions do not provide the appropriate resources or support necessary to institute an effective response for cultural change (

4). This lack of scaffolding leads to an exacerbation of the “minority tax” (

3), thereby placing more duress on the very same people adversely affected by structural racism. As a result, many in DEI leadership positions have become frustrated and disillusioned with the lack of institutional and/or financial support and commitment, leading many to leave academia and organized medicine (

4–

6).

Academic psychiatry must acknowledge the role that our field has played in creating and perpetuating racist structures and ideas. From this place of recognition, DEI leaders are uniquely poised to use their expertise in understanding attitudes, emotions, behavioral changes, and trauma in order to move toward reconciliation. Implementing strategic decisions related to antiracism and DEI is critically important to promote academic excellence in research, clinical care, and education. Patients, medical students and residents, physicians, and scientists who identify as BIPOC are struggling with the weight of racism and inequity. DEI leaders are critical in guiding departments and institutions across the country to develop structural changes to promote resilience. Below, we outline the current landscape of DEI leadership within psychiatry at academic medical centers and share our vision for how this important role should be structured and compensated.

Current Landscape of Diversity Leaders

We represent DEI leaders at public and private psychiatry departments across the country. Our departments include seven of the top 10 psychiatry departments, according to the 2020

U.S. News & World Report rankings (

7). In our small sample (N=9), all are women, and eight (89%) are BIPOC. The mean age is 46 years (range, 40–51 years), seven (77%) are mothers, and four (44%) are informal caregivers of seriously ill family members. Over half of us are the primary breadwinner of their family and/or provide financial support to extended family. The majority of us are psychiatrists, with one psychologist in the sample. In academic rank, our range includes two assistant professors, four associate professors, and three full professors.

We have a wide range of DEI titles, falling into three categories: vice or associate chairs (33%), directors (22%), and diversity ambassadors/members or chairs of diversity committees (44%). Five (56%) of us sit on departmental executive committees. Only one holds a named endowed chair, and four (44%) of us received no compensation or salary support for these roles. For those of us who do receive salary support, the average compensation is $48,000 (range, $10,000–$100,000), representing approximately 18% (range, 5%−36%) of total salary. This is lower than the estimated average effort we report investing in these roles (23%; range, 10%−30%). The unpaid leaders among us estimate spending 16% effort on DEI activities, on average (range, 10%−30%). Only three (33%) of us are provided with support staff (e.g., an administrative assistant), at 25% effort (range, 5%−50%). Five (55%) of us received some discretionary support (average, $27,800; range, $2,000–$100,000), and only two of those five have these funds renewed annually.

Challenges of Limited Representation of Women and BIPOC Faculty in Leadership Positions

DEI roles are challenging for several reasons. Leadership hurdles are often higher for BIPOC women than White men and women, leading to attrition with limited representation (

8–

10). BIPOC women face additional challenges due to the influence of race and ethnicity on perceptions of leadership (

11). BIPOC women experience issues of intersectionality, meaning that they must disentangle whether to attribute workplace discrimination to gender, race, or other aspects of their identity (e.g., disability, sexual orientation) (

12).

Leadership Hurdles and Lack of Representation

BIPOC psychiatry faculty typically endure discrimination and lack peers who look like them to provide support. In 2019, inequities in retention and promotion of psychiatric faculty at U.S. medical schools were prominent. White male psychiatrists were promoted to full professor rank at a full-professor-to-assistant-professor ratio of 0.74 (

13). For White women, the ratio lagged far behind at 0.26, similar to Black men at 0.24. For BIPOC women, the full-professor-to-assistant-professor ratio was 0.14, and, concerningly, the ratio for Black women was 0.08. A similar imbalance is seen at the highest levels of leadership, with White males comprising 61% of psychiatry department chairs, compared with 17% for White women, 3.9% for Latino men, 1.9% each for Latina women and Black women, and 0.6% for Black men. Finally, there is an absence of mentors and sponsors who can identify meaningful roles and advise DEI leaders on how to reduce less rewarding tasks and successfully advance in academia. Frequently, their work is devalued, which contributes to isolation and burnout (

14).

Minority Tax

Because of the limited numbers of BIPOC women in psychiatry faculty positions, many DEI leaders face isolation, excessive time burdens, and additional “taxes” on their time. This double minority tax (gender and racial/ethnic underrepresentation in medicine) limits their ability to be effective (

2). In order to demonstrate institutional diversity, BIPOC faculty are frequently asked to serve on committees, liaise with community groups, and mentor students, but such work is not compensated or part of promotional activities (

15). DEI leaders are also often asked to oversee cultural humility and antiracism courses and serve as “supermentors” of trainees, also uncompensated. This results in unique harms, including decreased pay, uncompensated labor, and scholarship that is not recognized or is devalued, resulting in moral injury.

Family Caregiving Responsibilities

A large proportion of our DEI leader sample are also mothers, informal caregivers, and/or provide financial support to extended family members (common for BIPOC women earners [

16]), exemplifying both the vulnerability and the resilience of these leaders. Studies have shown that physician mothers experience discrimination at work and are at risk for burnout and mental health issues (

4,

8).

Essential Community Support Needed for DEI Leadership

To consider next steps in alleviating the challenges facing BIPOC women in DEI positions within psychiatry, a small group of DEI leaders convened at the annual meeting of the American Psychiatric Association (APA) in San Francisco in May 2019. DEI leaders shared common concerns and challenges. The group agreed to meet regularly for support, scholarship, and the promotion of equity in academic medicine. This group not only provides a space for sharing lived experience but also offers a respite for the trauma endured by oppressive structures within academic psychiatry. The space is liberating in that it allows BIPOC DEI leaders to speak openly about hurtful, discriminatory experiences without feeling forced, as they do in other settings, to minimize the impact of these experiences. In short, this is a place for disagreement, tears, support, and processing of sexist and/or racist experiences.

Additionally, this group provides critical peer mentorship through sharing of different institutional cultures and the ingredients for success and pitfalls in leading diversity efforts. Given the limited numbers of BIPOC women among senior faculty, finding mentors can be challenging. Peer support and mentorship are critical ingredients to success. In addition to mentorship, these communities provide an “old girls” network, which can lead to an increase in sponsorship and opportunities.

Supporting BIPOC Women in DEI Leadership in the Face of Two Pandemics

As our nation faces two national pandemics—COVID-19 and racism—we believe this is the ideal time to reenvision DEI leadership positions in psychiatry. During the COVID-19 pandemic, women are at risk for adverse psychological impacts, and early evidence shows productivity declines among women in academia (

17–

19). The financial toll of the COVID-19 pandemic has also resulted in heightened stress for many DEI leaders who are the primary breadwinners in their household. Although the increased attention that has been given to structural racism is an outstanding step forward for our country, the case vignette exemplifies the rush to quickly address long-standing and complex racial inequities, with departments hastily creating DEI positions only to check a box as having “done something” (

4). Such performative responses may set up new DEI leaders for failure, and may thus provide fodder later for claims that DEI efforts were not effective. Furthermore, research shows that leaders point to the existence of DEI structures as proof that there is equity and fairness, while ignoring information about continued discrimination—despite the necessity for white people with institutional power to address structural racism (

15).

As DEI leaders at major psychiatry departments across the country, we have thrived in academia not despite but because we are BIPOC women, mothers, informal caregivers, and breadwinners. In this piece we intentionally highlighted the intersectional experiences of women in diversity roles. In addition to being from two historically excluded groups (gender and racial/ethnic minorities), many of us hold responsibilities in our households that have an impact our leadership roles. This focus was necessary, given how little emphasis is placed on the experience of women in leadership roles, especially those from racial/ethnic minority backgrounds. We do think, however, that understanding the male perspective is an area worth pursuing in the future, as data on these experiences will likely provide a valuable comparison.

In conclusion, DEI efforts should not be isolated from the power structures within a department, but instead should be integrated into the highest levels of decision making to ensure a presence and active voice in any setting where real power is wielded.

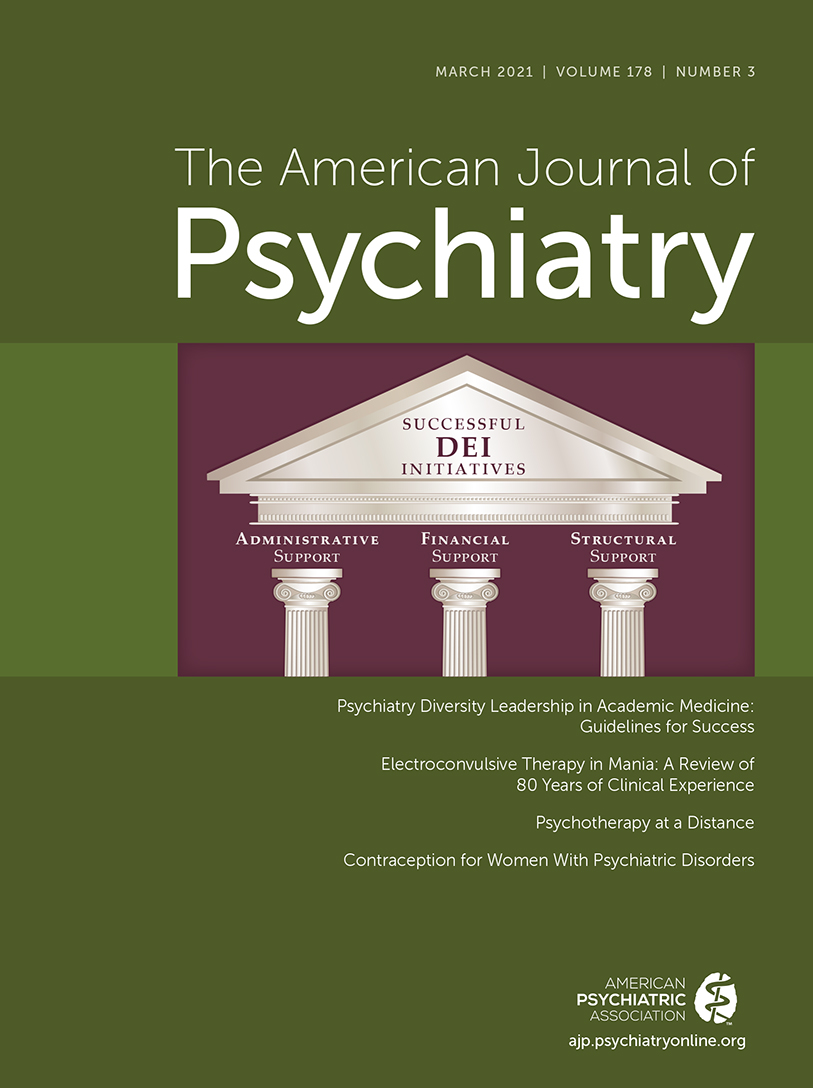

Box 1 provides recommendations for the necessary support for the success of DEI leadership. Only through adequate financial, administrative, and structural support can inclusive excellence begin to be infused into all departmental activities.