Racialized disparities in mental health outcomes are a significant ethical issue in the United States and a systemic challenge that needs to be addressed by both clinicians and researchers. For clinicians, racial disparities in mental health represent a failure of the field to appropriately engage and equitably treat individuals suffering from psychiatric disease. For researchers, limited investigation into the causes and mechanisms of race-related differences in mental health perpetuates scientific ignorance that contributes to the inequality observed at the provider level.

One particularly concerning domain where racial disparities are observed is in psychotic spectrum disorders, which contribute to significant social and emotional strain on affected individuals and their families. Notably, the rates of psychosis diagnosis are higher in Black communities (

1). Differing rates of diagnosis may be due in part to mischaracterization of cognition and behavior in Black individuals (

2). However, these differential rates may also be related to racialized differences in exposure to psychosis risk factors. It can be argued that limited attention in the field has been given to the unique ways in which race and racial experiences are linked to psychosis risk factors. Characterizing the racialized nature of these risk factors is not only critical for addressing racial disparities in psychotic disorders but also essential for rectifying disparities across psychiatric disease.

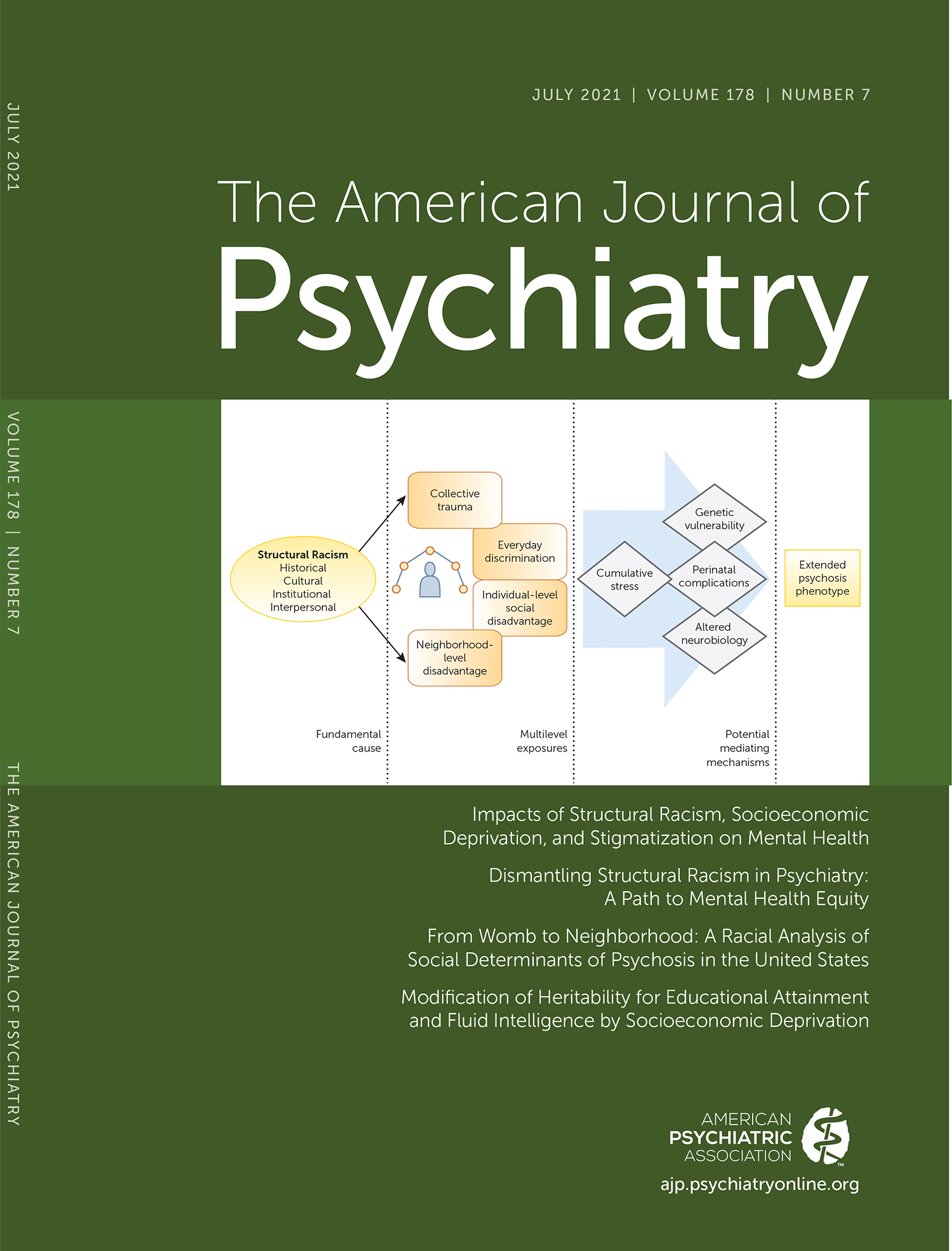

In this issue of the

Journal, Anglin and colleagues (

3) provide an important critical review of risk factors for psychosis that disproportionately burden Black and other minority group individuals. Chiefly, the review focuses on social determinants of risk, such as stress during pre- and perinatal periods of pregnancy, trauma exposure, and neighborhood characteristics, given that each of these categories is highly racialized. That is, there are evident race-related differences in these stressful experiences that likely relate to race-related differences in the prevalence of psychotic disorders.

Acknowledgment that these experiences are racialized should not be controversial, given the ample evidence reviewed by Anglin and colleagues that demonstrates that Black individuals—in general—experience more stress during pregnancy, are exposed to more childhood trauma, and reside in more economically disadvantaged and deprived areas in the United States. Although racialized experiences affect many marginalized groups, for brevity, we focus our commentary largely on disparities affecting Black individuals.

It is crucial for readers to understand, as Anglin and colleagues note, that the racialized social determinants are

systemic as they are uniquely ingrained in U.S. norms and societal practices that exist, in part, to perpetuate racial inequities. For example, the authors note the potential role of collective racial trauma in exacerbating mental health issues in the Black community, with one pertinent issue being the greater police victimization of Black men compared with White men (

4). The difference in police victimization is thus racialized, but it is also systemic given the history of policing in the United States. Although not the only origin, modern policing is inextricably tied to norms around the control of Black and brown people from slavery through the Jim Crow era, and thus it is part of an inescapable historic trauma for many Black individuals (

5). Systemic inequalities in the United States extend far beyond policing, however, to the point where minority communities are disproportionately exposed to pollutants generated by nonminority groups (

6). As outlined through these types of data, it is appropriate to refer to the racialized inequities that we observe as a product of structural racism. In light of contemporary events within the medical field, we highlight that “racism” is not purely an overt, motivated act perpetuated by an individual or of one group toward another. Rather, it encompasses both the overt and covert, as well as the intentional and

unintentional actions that perpetuate discrimination toward, and inequity between, racial groups.

However, potentially racialized aspects of trauma exposure are not well appreciated within the field, despite wide agreement that trauma plays a key role in the development of many psychiatric conditions, including psychosis (

7). While traumatic events can be experienced by anyone, the contexts of these events may differ between Black and White individuals, which in turn may augment the development of psychopathology. Greater emphasis is needed on understanding potential unique effects of trauma on Black individuals as well as the modulatory effects of structural racism. One of the largest studies of trauma that predominantly focuses on traumatized Black individuals is the Grady Trauma Project (∼90% Black, ∼60% Female), which has interviewed over 12,000 participants in Atlanta. In addition to seminal research characterizing dysfunction related to posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), emerging research highlights the unique and additive roles of racialized stressors in trauma-related psychopathology. Recent work from the Grady Trauma Project demonstrates that greater racial discrimination experienced by Black women exacerbates the effects of interpersonal trauma, contributing to heightened PTSD symptoms (

8). These findings are in line with a recent prospective emergency department study demonstrating that racial discrimination experienced by Black individuals is predictive of future PTSD symptoms (

9). Although these studies do not fully capture the breadth of racialized experiences for minoritized individuals, they highlight the additive effects of racism in relation to psychiatric disease, which has received limited attention to date.

It is currently unclear how structural racism may affect neurophysiological systems that mediate psychotic symptoms. As Anglin and colleagues note, components of structural racism such as neighborhood-level factors and collective racial trauma may have effects across generations. Transgenerational transmission of traumatic stress through the epigenome that modulates stress-regulation pathways has been observed (

10), and a similar mechanism may play a role in mediating the development of psychotic symptoms. Further, recent neuroimaging research has found that race-related differences in adversity may modulate activity within core emotion-related neural circuitry (

11). The emerging literature highlights potential direct biological impacts of structural racism, which are relevant both for understanding the development of psychiatric disorders and for translational efforts toward personalized treatment approaches. However, given the present dearth of research, there is a critical need for expanded research specifically investigating the impact of racialized stressors on neurobiology to enable a better understanding of race-related differences in psychosis.

In light of the review by Anglin and colleagues, and contemporary acts of racial injustice in society, as well as in psychiatry and medicine, the salient question for readers of the Journal should be, “What can be done to address racial disparities that have an impact on the development of psychosis and more broadly across other psychiatric disorders?” Rectification of these disparities within psychiatry requires effort from clinicians and researchers. For clinicians, it is necessary to adopt more culturally and socially informed practices and to develop more informed interventions, as noted by Anglin and colleagues. Structural racism encapsulates stress components that infiltrate multiple levels of life, from global neighborhood characteristics to individual traumatic events, and even to daily social interactions. Understanding how stressors are racialized and interwoven into clinical presentations and assessments is necessary for addressing race-related differences in psychosis. More generally as a field, we must acknowledge the multilevel impacts of structural racism for the development of effective individualized treatment and intervention programs to reduce racial disparities in the prevalence of psychiatric disorders.

Basic, clinical, and translational researchers must also consider the potential influence of structural racism on outcomes and moderators of interest. Current research already suggests that adversity and trauma disrupt typical brain and behavioral processes, which contributes to psychiatric disease. Limited attention, however, has been given to the fact that improper consideration of race-related differences can result in biased models or algorithms that may have deleterious effects on future policy decisions (e.g., health care policy) (

12). These biases are further exacerbated by the lack of representation of participants from Black and other minoritized groups in research studies (

13). Thus, appropriate contextualization of the racialized nature of many stressors, in addition to increased recruitment of participants from minoritized groups, is critical for future research on psychosis and on psychiatric disorders in general.

However, the task of addressing racial disparities in relation to psychiatric disorders is not simply a task for individual practitioners and researchers—it requires systemic change across academic psychiatry. As a first step toward this change, we echo a recent important suggestion by Stevens and colleagues in the journal

Cell: fund Black scientists (

14). Data from the National Institutes of Health highlight that racially minoritized scientists are funded at lower rates, yet these individuals more often focus applications toward addressing health disparities. Given the need for extramural funding for research projects and career success, lack of funding for Black and minoritized scientists likely contributes to the lack of research on racial disparities in psychiatric disease and the unfortunate attrition of these scholars from the field. Addressing this funding gap may thus facilitate enhanced research on mechanisms underlying impacts of racialized stressors on mental health while facilitating the development of a diverse pool of investigators.

In summary, the important review by Anglin and colleagues highlights a problematic knowledge gap as to how racialized structural inequities perpetuate disparities in psychotic disorders. It also provides compelling data to prioritize the consideration of the role of structural racism in mediating psychiatric diseases. Future clinical practice and research must begin to focus attention on the consequences of structural racism on psychological and physiological processes relevant to mental health. The recommendations proposed by Anglin and colleagues should be taken seriously and accompanied by a corresponding shift in funding and training priorities to address the impacts of structural racism, both on psychotic disorders and on psychiatric diseases in general.