THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

EDITOR

Nancy C. Andreasen, M.D., Ph.D.

DEPUTY EDITORS

Arnold M. Cooper, M.D.

Jack M. Gorman, M.D.

EDITORIAL STAFF

Managing Editor

Sandra L. Patterson

Assistant Managing Editor

Linda A. Loy

Senior Assistant Editors

Laura M. Little Jane Weaver

Assistant Editor

Marjorie M. Henry

Production Editor

Beverly M. Sullivan

Production Assistant

Michael D. Roy

Administrative Assistant

Dawn Baldwin

Editorial Secretaries

Sherill L. Johnson Alice M. Ruhling

EDITOR EMERITUS

John C. Nemiah, M.D.

ASSOCIATE EDITORS

Paul S. Appelbaum, M.D.

Dan G. Blazer, M.D., Ph.D.

Gabrielle A. Carlson, M.D.

Kenneth L. Davis, M.D.

Judith H. Gold, M.D.

John G. Gunderson, M.D.

Roger E. Meyer, M.D.

Charles F. Reynolds III, M.D.

Steven S. Sharfstein, M.D.

David Spiegel, M.D.

Carol Tamminga, M.D.

Ming T. Tsuang, M.D., Ph.D., D.Sc.

Gary J. Tucker, M.D.

George E. Vaillant, M.D.

STATISTICAL EDITORS

Stephan Arndt, Ph.D.

John J. Bartko, Ph.D.

FORMER EDITORS

Amariah Brigham, M.D.

1844–1849

T. Romeyn Beck, M.D.

1849–1854

John P. Gray, M.D.

1854–1886

G. Alder Blumer, M.D.

1886–1894

Richard Dewey, M.D.

1894–1897

Henry M. Hurd, M.D.

1897–1904

Edward N. Brush, M.D.

1904–1931

Clarence B. Farrar, M.D.

1931–1965

Francis J. Braceland, M.D.

1965–1978

The American Journal of Psychiatry, ISSN 0002-953X, is published monthly by the American Psychiatric Association, 1400 K Street, N.W., Washington, DC 20005. Subscriptions (per year): U.S. institutional $85.00, individual $60.00, student $30.00; Canada and foreign institutional $115.00, individual $90.00, student $45.00. Single issues: U.S. $7.00, Canada and foreign $10.00.

Business communications, address changes, and subscription questions from APA members should be directed to the Division of Member Services: (202) 682-6069. Nonmember subscribers should contact the Circulation Department: (202) 682-6158. Authors who wish to contact the Journal editorial office should call (202) 682-6020 or fax (202) 682-6016; Journal Calendar: (202) 682-6026.

Business Management: Nancy Frey, Director, Periodicals Services; Laura G. Abedi, Advertising Production Manager: (202) 682-6154; Beth Prester, Director, Circulation; Elizabeth Flynn, Promotion Manager; Jackie Coleman Young, Fulfillment Manager.

Advertising Sales: Raymond J. Purkis, Director, 2444 Morris Avenue, Union, NJ 07083; (908) 964-3100.

Pages are produced using Xerox Ventura Publisher, Microsoft Windows version. Printed by The William Byrd Press, Inc., Richmond, VA., on acid-free paper effective with Volume 140, Number 5, May 1983.

Second-class postage paid at Washington, DC, and additional mailing offices. POSTMASTER: Send address changes to The American Journal of Psychiatry, Circulation Department, American Psychiatric Association, 1400 K St., N.W., Washington, DC 20005.

Indexed in Abstracts for Social Workers, Academic Abstracts, Biological Abstracts, Chemical Abstracts, Chicago Psychoanalytic Literature Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing Literature, Excerpta Medica, Hospital Literature Index, Index Medicus, International Nursing Index, Nutrition Abstracts, Psychological Abstracts, Science Citation Index, Social Science Source, and Social Sciences Index. The complete text of the Journal is available on the BRS database, BRS Information Technologies, Inc., Latham, NY.

The American Psychiatric Association does not hold itself responsible for statements made in its publications by contributors or advertisers. Unless so stated, material in The American Journal of Psychiatry does not reflect the endorsement, official attitude, or position of the American Psychiatric Association or of the Journal’s Editorial Board.

Authorization to photocopy items for internal or personal use, or the internal or personal use of specific clients, is granted by the American Psychiatric Association for libraries and other users registered with the Copyright Clearance Center (CCC) Transactional Reporting Service, provided that the base fee of $00.75 per copy is paid directly to CCC, 21 Congress St., Salem, MA 01970. 0002-953X/94/$00.75.

This consent does not extend to other kinds of copying, such as copying for general distribution, for advertising or promotional purposes, for creating new collective works, or for resale. APA does not require that permission be obtained for the photocopying of isolated articles for nonprofit classroom or library reserve use; all fees associated with such permission are waived.

Copyright © 1994 American Psychiatric Association.

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

Sesquicentennial Anniversary Supplement, 1844–1994

Editor’s Introduction N.C.A.

I. ATTITUDES AND POLICIES

Introduction Howard H. Goldman

Asylums Exclusively for the Incurable Insane (1844) Amariah Brigham

The Moral Treatment of Insanity (1847) Amariah Brigham

Gheel (1851) Pliny Earle

A Sketch of the History, Buildings, and Organization of the Pennsylvania Hospital for the Insane (1845) Thomas S. Kirkbride

Address Before the Fiftieth Annual Meeting of the American Medico-Psychological Association, Held in Philadelphia, May 16th, 1894 S. Weir Mitchell

Some Remarks on the Address Delivered to the American Medico-Psychological Association, by S. Weir Mitchell, M.D., May 16, 1894 Walter Channing

A Short Sketch of the Problems of Psychiatry (1897) Adolf Meyer

The Attitude of Neurologists, Psychiatrists and Psychologists Towards Psychoanalysis (1939) Abraham Myerson

Some Trends of Psychiatry (1944) Abraham Myerson

Benjamin Rush and American Psychiatry (1944) Clifford B. Farr

The Rôle of Psychiatry in the World Today (1947) William C. Menninger

Current Trends in German Psychiatry (1949) Kurt Schneider

Reminiscences: 1938 and Since (1990) John Romano

II. CLINICAL DESCRIPTION

Introduction David Spiegel

Definition of Insanity—Nature of the Disease (1844) Amariah Brigham

Katatonia: A Clinical Form of Insanity (1877) James G. Kiernan

The Curability of Insanity. A Statistical Study (1885) Pliny Earle

Personality Changes and Upheavals Arising Out of the Sense of Personal Failure (1926) A.T. Boisen

The Onset of Schizophrenia (1927) Harry Stack Sullivan

In Memoriam: Emil Kraepelin (1927) Adolf Meyer

The Acute Schizoaffective Psychoses (1933) J. Kasanin

Symptomatology and Management of Acute Grief (1944) Erich Lindemann

Irrelevant and Metaphorical Language in Early Infantile Autism (1946) Leo Kanner

III. RESEARCH: METHODS, MECHANISMS, AND CAUSES

Introduction Dan G. Blazer

The Importance of a Correct Physiology of the Brain, as Applied to the Elucidation of Medico-Legal Questions; and the Necessity of Greater Accuracy and Minuteness in Reporting Post Mortem Examinations (1845) N.S. Davis

Statistics of Insanity (1849) Amariah Brigham

A Review of the Signs of Degeneration and of Methods of Registration (1896) Adolf Meyer

Influenza and Schizophrenia (1926) Karl A. Menninger

The Genetic Theory of Schizophrenia (1946) Franz J. Kallmann

The Concepts of “Meaning” and “Cause” in Psychodynamics (1947) John C. Whitehorn

Cerebral Blood Flow and Metabolism in Schizophrenia (1948) S.S. Kety, R.B. Woodford, M.H. Harmel, F.A. Freyman, K.E. Appel, and C.F. Schmidt

Research and Its Support Under the National Mental Health Act (1949) Lawrence C. Kolb

IV. DEVELOPMENTS IN SOMATIC TREATMENT

Introduction Carol A. Tamminga

Observations on the Medical Treatment of Insanity (1850) Samuel B. Woodward

The History of the Malarial Treatment of General Paralysis (1935) (Comment and Translation by Walter L. Bruetsch, 1946) Julius Wagner-Jauregg

Prefrontal Leucotomy in the Treatment of Mental Disorders (1937) Egas Moniz

The Methodical Use of Hypoglycemia in the Treatment of Psychoses (1937) Manfred Sakel

Curare: A Preventive of Traumatic Complications in Convulsive Shock Therapy (1941) A. E. Bennett

Ugo Cerletti, M.D. (photograph)

The Society of Alcoholics Anonymous (1949) William W.

The Use of Antabuse (Tetraethylthiuramdisulphide) in Chronic Alcoholics (1950) S. Eugene Barrera, Walter A. Osinski, and Eugene Davidoff

Chlorpromazine Treatment of Mental Disorders (1955) Vernon Kinross-Wright

Pierre Deniker, M.D. (photograph)

Clinical Findings in the Use of Tofrānil in Depressive and Other Psychiatric States (1959) Benjamin Pollack

The Use of Lithium in the Affective Psychoses (1966) Ralph N. Wharton and Ronald R. Fieve

Index to Illustrations

THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

: Sesquicentennial Anniversary SupplementEditor’s Introduction

This special supplement of The American Journal of Psychiatry celebrates the 150th anniversary of both the American Psychiatric Association and its official journal. The American Journal of Psychiatry, at 150 years of age, is the oldest continuously published medical specialty journal in the United States. This commemorative supplemental issue is being distributed to all subscribers as an anniversary gift. We hope that its contents will provide resources for introspection, reappraisal, and growth. As psychiatrists know better than perhaps any other medical specialty, studying the past is the best way to understand the present and to change the future. As we take stock of our profession at its 150th anniversary, we can learn a great deal from the work of our predecessors.

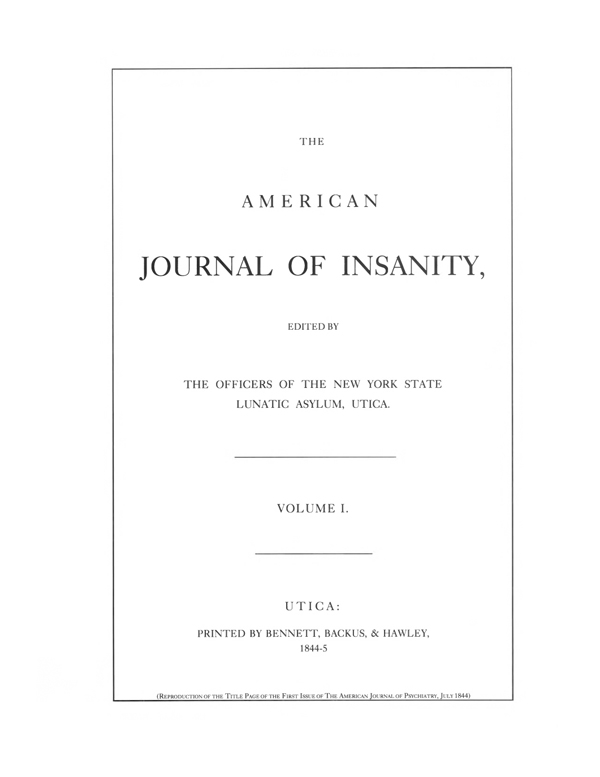

THE HISTORY OF THE AMERICAN JOURNAL OF PSYCHIATRY

When the original founders of the APA decided to join together in 1844 to share ideas about the best way to provide care for the mentally ill in our young country, they needed a way to communicate with one another on a regular basis. The American Journal of Psychiatry became that mechanism. One of the founders, Amariah Brigham, assumed responsibility for editing the new journal. Brigham was a self-made and largely self-educated man who apparently aspired from childhood to be a physician, but was nearly deprived of this opportunity through the loss of his father at age 11 and his uncle, a physician who adopted him and began training him, at age 12. He worked at a variety of jobs thereafter and eventually was able to obtain an apprenticeship and then to spend a year attending lectures at the College of Physicians and Surgeons in New York. During that year he also taught himself French! He spent a number of years as a family practitioner, but was eventually called to become superintendent for the Hartford Retreat for the Insane in 1840 and subsequently at the New York State Lunatic Asylum in Utica in 1842. He founded The American Journal of Insanity (not given its present name until 1921) while at Utica, publishing it largely at his own expense. The journal soon established itself as the premier scholarly publication in the field of mental illness in the United States.

As will be evident from the selections from Brigham’s work that are republished in this supplement, Brigham was an excellent writer, a thoughtful physician, and a compassionate human being. Many of the articles that he wrote in order to help the fledgling journal take flight are models of clinical thinking that would grace any era. They are still fresh and interesting now, 150 years later. After his death in 1849, Brigham was succeeded by T. Romeyn Beck (1849–1854) and subsequently by John P. Gray (1854–1886). Gray was particularly interested in the physical causes of mental illness, took a strong stand against those who argued that mental illnesses were due to sin and more properly treated by the clergy, established the first neuropathology laboratory in the United States at Utica, and published many articles that explored the biology of the brain. His successor, G. Adler Blumer (1886–1894), had a strong interest in rehabilitative therapy, the elimination of the use of restraint, and the creation of a good therapeutic milieu. Blumer was the last of the “Utica editors.” In 1894 the journal was sold to the American Medico-Psychological Association (forerunner of our APA) for the sum of $944.50, thereby becoming its official journal. Since its original founding, only 11 individuals have served as editors of The American Journal of Psychiatry. The other editors are Richard Dewey (1894–1897, Henry M. Hurd (1897–1904), Edward N. Brush (1904–1931), Clarence B. Farrar (1931–1965), Francis J. Braceland (1965–1978), John C. Nemiah (1978–1993), and myself.

THE CONTENTS OF THE COMMEMORATIVE ISSUE

As the sesquicentennial year approached, the editorial staff of the journal began to address the question of how to honor the long history of the journal and its past editors. After considerable discussion, it was decided that the best way would be to republish some selected examples of its prior contents from the past 150 years. Many of the early articles that were published in the journal, particularly those from its very early years, are available only in a few special libraries and therefore are inaccessible to most subscribers. Reprinting them in a commemorative issue would make them widely available.

But what to choose? A journal that is 150 years old has published thousands of manuscripts in thousands and thousands of pages. While most contributors no doubt viewed their submissions as gems, finding the highest quality diamonds and placing them in the best setting required both thought and effort. Should we sample one article per decade to try to ensure equal representation? Should we stratify by topic? Should we choose a particular topic and trace its history? Should we focus on recent accomplishments and stress the extraordinary progress that has occurred in diagnosis and treatment during the past several decades? Or should we reflect the long sweep of our history, with all its strengths and weaknesses?

Your current editor long ago passed from the healthy state of bibliophilia to the diseased but exhilarating condition of bibliomania. (The diagnostic criteria involve features such as spending large sums on books, buying more than are really necessary, experiencing the aroma of library dust as pleasurable, and endorsing the delusional belief that reading books or scholarly articles is better for the brain than watching television.) She concluded that the best gift to the membership would be to share the inaccessible treasures of the earlier issues by selecting a limited number of especially interesting older articles. This approach would not provide “continuing medical education” about what to do in the here and now, nor would it convey a Panglossian message that we are steadily getting better and better in our progress toward the best of all possible worlds. But it would reveal the recurrent themes that have perplexed psychiatrists as they have struggled with defining the structure and purpose of their specialty, both as it relates to other medical disciplines and as it relates to the care of patients. And it would also identify some notable peaks in the broad landscape of a broad medical specialty.

Most of the articles reprinted in this issue are drawn from the first 100 years of The American Journal of Psychiatry, since they are least accessible to the average reader. They are reprinted in their original form, including the quirks of language and spelling, as well as the occasional social and cultural biases, that characterize earlier eras. (Lest we feel too smug, we should realize that readers will also find us strange and insensitive 150 years from now, in ways we could not currently predict.) They are divided into four broad categories: Attitudes and Policies, Clinical Description, Research Methods: Mechanisms and Causes, and Developments in Treatment. Each of these four sections is introduced by an overview, written by one of the current members of the journal’s Editorial Board.

In general, these categories reflect the contents of The American Journal of Psychiatry during its long history. The earliest paper is from the first issue of this journal and was written by Amariah Brigham (1844), while the most recent describe the therapeutic efficacy of lithium (1966) and the reminiscences of John Romano as he contemplated the upcoming sesquicentennial (1990). Some document landmarks in our history, such as the report of methods for measuring cerebral blood flow by Kety (1948), the foundation of the National Institute of Mental Health (1949), and the development of new treatments such as insulin coma (1937) or chlorpromazine (1955). Some reflect the emergence of new nosological conceptualizations, such as catatonia (1877) and schizoaffective disorder (1933). Some describe the desperate cures that were developed to improve patient care in the prepharmacologic era, such as malarial treatment for general paresis and prefrontal leucotomy for psychosis. It is notable that the two Nobel prizes that have been awarded in physiology or medicine for achievements in psychiatric treatment were given to Wagner-Jauregg and Moniz for these two desperate cures, while the achievements of developing antipsychotics, antidepressants, antianxiety agents, and lithium have not been honored, nor have the forward-looking techniques of measuring cerebral blood flow (Kety), nor the introduction of elegant designs for examining gene-environment interactions (Kallman). As we read these works from the past and reflect on the occasional follies of our field, we can take comfort in the fact that we have been far from alone in embracing treatments or ideas that are later recognized as suboptimal.

WHAT CAN WE LEARN FROM OUR HISTORY?

The contents of this issue indicate that many of the struggles we currently confront in psychiatry have been with us throughout most of our history. Many of the themes presented in these articles have been replayed repeatedly.

In one of the earliest articles to appear in the journal, Amariah Brigham discusses the issue of isolation versus mainstreaming of psychiatric patients (and their physicians). Brigham comes down on the side of integration, and Pliny Earle’s description of Gheel is an illustration of the benefits and problems of “community treatment” from a mid-nineteenth century perspective. On the other hand, Kirkbride devoted a career to developing ideal designs for hospitals devoted to the exclusive treatment of the mentally ill. Weir Mitchell gives psychiatry a scathing criticism for its isolationism at the time of the 50th anniversary of APA, while Meyerson reflects on our boundaries with neurology and psychology and the special position of psychoanalysis. Plus ça change, plus c’est la même chose.

Lest we think that our forefathers represented immutable archetypes of extreme positions, we are also given reminders of their intellectual flexibility. Adolph Meyer wrote repeatedly about the importance of biological approaches to understanding mental illness and even proposed methods for measuring physiognomy (1896). Karl Menninger proposed an infectious disease theory for schizophrenia many years (1925) before the current viral theories became fashionable again.

There are also many indications of the wisdom and prescience of our forefathers and the editors who accepted their articles for publication. (Alas, there were no foremothers in these early years.) Both Brigham and Earle, in a pre-statistical and pre-epidemiological era, argue for the importance of carefully collecting accurate data. Before contemporary health care reform and the emphasis on measuring the “bottom line,” they stress the importance of valid measures of outcome and the foolishness of counting patients as “cured” on discharge when they often return again for repeated “cures” on multiple occasions. Davis argues for the value of sound and accurate post-mortem brain data. Boisen and William W. present insights about mental illness based on a patient’s personal experience; these reports advocated for the patient’s perspective and the value of patient support groups before advocacy became widely organized.

The contents of this issue also serve to remind us that we may be both bigger and better than we sometimes think. Our playing field is large, and we should not forget how large it has historically been. Psychiatrists have traditionally cared for a broad range of patients and illnesses. For example, psychiatrists were the primary physicians to treat general paresis before the development of penicillin. A psychiatrically oriented scientist developed the methods and models that form the foundation for modern techniques for measuring brain metabolism with positron emission tomography or single emission photon computed tomography. (Although not documented here, psychiatrists also developed EEG, the Nissl stain, and Brodmann’s maps of brain cytoarchitectonics.)

We also see that major contributions can arise from practicing clinicians and small medical centers, not just from large and powerful research institutions. The best early report of the efficacy of antidepressants in the journal was done by a clinical practitioner at Rochester State Hospital, and the value of curare for modifying ECT was discovered in Nebraska rather than New York or Boston.

Reviewing the contents of The American Journal of Psychiatry over the past 150 years in order to select the contents of this issue, while inhaling library dust into the wee hours of the morning, was in fact a source of considerable pleasure. The contents of this issue represent a distillation of that pleasure, chosen to give the gems of wisdom produced by our predecessors back again to our readers. Enjoy.

N.C.A.