Differential Diagnosis

Common causes of fever include infections, noninfectious inflammatory diseases, neoplastic disease, drug-related fevers, endocrine disorders, factitious disease, and hyperthermia (

Table 1–1). The most common

infections that cause fever are pneumonia, acute upper respiratory illness, cellulitis, urinary tract infection, and superficial abscess. In general, patients with pneumonia and upper respiratory infections present with a history of fever, productive cough, and shortness of breath. Treatment is dependent on the severity of the illness, comorbid factors, and suspected organism (bacterial or viral).

Intra-abdominal infections that may require surgery, such as appendicitis, cholecystitis, and diverticulitis, should be suspected in a patient with fever, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, and/or abnormal liver function test results. These patients may require surgical consultation in the emergency department (ED) in addition to tests such as a sonogram, computed tomography (CT) scan, or hepatobiliary iminodiacetic acid scan.

Patients with altered mental status, fever, neck stiffness, photophobia, headache, and rash should be immediately suspected of having meningitis. These patients require isolation, immediate broad-spectrum intravenous antibiotics, and a lumbar puncture. Common organisms include Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenzae, Neisseria meningitidis, and viral organisms. Listeria monocytogenes and resistant S. pneumoniae must also be addressed with antibiotics. Treatment should not be delayed if lumbar puncture cannot be performed in a timely fashion in highly suspected cases.

Patients who have fever, chills, tachycardia, and symptoms of congestive heart failure (i.e., dyspnea, frothy sputum, and chest pain) may have endocarditis. A common trigger may be recent dental work. Physical examination may reveal a new heart murmur, retinal hemorrhage (Roth spots), nodules on fingers or toes (Osler nodes), and plaques on the palms and feet (Janeway lesions). These patients require evaluation in the ED. Workup includes multiple blood cultures drawn at intervals, intravenous antibiotics, and an echocardiogram. Common organisms are viridans streptococci, Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and various fungal organisms.

Sepsis is a condition in patients with suspected infection who have at least two of the following: fever or hypothermia, tachycardia, tachypnea, leukocytosis or leukopenia, or 10% bandemia. Intravenous normal saline, antipyretics, intravenous antibiotics, consultations, and additional tests will likely be needed. Septic shock is defined by sepsis with hypotension that is refractory to adequate fluid resuscitation. Patients with suspected sepsis or septic shock will need to be evaluated and treated immediately in the ED of a well-equipped general hospital.

Among febrile cases of noninfectious inflammatory diseases, clinicians must first consider the possibility of thromboembolic phenomena. Both deep vein thrombosis and pulmonary embolism can cause low-grade fevers. Collagen vascular diseases such as systemic lupus erythematosus and rheumatoid arthritis can also cause low-grade fevers with or without other infectious symptoms. Patients with temporal arteritis can present with fever with no clinical symptoms or may have some temporal tenderness. The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is usually markedly elevated (to greater than 50 mm/hour). Because blindness is a potential complication, the diagnosis of temporal arteritis should be actively pursued with arterial biopsy, preferably prior to corticosteroid treatment.

Fever is a well-recognized manifestation of malignant neoplasms. A number of mechanisms have been proposed for the cause of such fevers, including tumor necrosis, inflammation, and increased heat production from the tumor cells themselves. Lymphomas are the neoplasms most commonly associated with FUO (

Cunha et al. 2005).

Patients with neutropenia and fever should be aggressively treated, and the source needs to be actively pursued. Because of the possibility of death within 24–48 hours, these patients should be isolated and broad-coverage antibiotic therapy should be started immediately after blood cultures and urine cultures are taken. ED evaluation for hospital admission is recommended for these patients.

Drug fever is a disorder characterized by a febrile response that coincides with the administration of a drug in the absence of underlying conditions that can be responsible for the fever (

Table 1–2). Drug-induced hyperthermia is a common side effect of psychotropic drugs, and of stimulants, including amphetamine, cocaine, phencyclidine (PCP), and lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD). These effects are usually secondary to increased muscle activity, increased metabolic rate, impaired thermoregulation, and impaired heat dissipation (

Delaney 2001), which can present as NMS, malignant hyperthermia, and febrile rhabdomyolysis.

Fever is a well-known side effect of clozapine, with a reported incidence of up to 55%. It commonly occurs within 30 days of initiating treatment and lasts 2.5 days on average (

Martin and Williams 2013). Clozapine-induced fever may be dependent on the clozapine dose. This dose-related effect could be reflected by the level of C-reactive protein (CRP), with elevated CRP associated with a higher clozapine level (

Buist and Schauer 2016).

While it may be common for patients receiving clozapine treatment to have a benign fever, they are at risk of developing infections for a number of reasons. Clozapine can cause agranulocytosis, compromising the immune system with increased risk of infection. Other proposed mechanisms include drug-induced hyperglycemia, sedation or altered mental state, gastrointestinal hypomotility, and urinary incontinence or retention. There may be a relationship between elevated clozapine levels and infection, in part due to an increase in inflammatory markers leading to reduced clozapine metabolism. Patients receiving clozapine should be monitored closely, especially in the setting of infection, and dose adjustment should be considered to decrease the risk of serious side effects

(Clark et al. 2018).

A key feature that differentiates drug-related fever, or drug fever, from fever of other causes is that it generally disappears once the offending drug is stopped. The patient’s temperature may return to near normal within 48–72 hours after discontinuing the medication in drug fever. Furthermore, drug fever is usually characterized by a temperature greater than 102°F (38.9°C), but the severity can fluctuate from a low-grade temperature to an extremely elevated temperature with relative bradycardia. If fever is unexpected, particularly in a situation when a patient is otherwise clinically well or improving, then drug fever should be considered in the differential diagnosis. Drug fever, however, remains a diagnosis of exclusion, often suspected in patients with otherwise unexplained fever. Transient elevations of serum transaminase levels and peripheral eosinophilia may be suggestive of drug fever. Other findings include rash, hemolysis, or bone marrow suppression. Some patients may present with a serum sickness–like syndrome with rash, lymphadenopathy, arthritis, nephritis, and edema along with fever. Others may present with a systemic lupus erythematosus–like syndrome characterized by fever, arthralgias, and positive findings on the antinuclear antibody test.

Factitious fever is commonly produced by thermometer manipulation involving the use of external heat sources or substitute thermometers. Some people have induced fever by self-administering pyrogenic agents, mostly consisting of bacterial suspensions. This practice is usually done for secondary gain. Patients with factitious fever are generally women, and approximately 50% are in health-related fields (

Taylor and Hyler 1993). Generally, patients with factitious fever appear nontoxic. They are unresponsive to antipyretics, and their laboratory test results are normal.

Heat-related illness (hyperthermia syndrome) progresses as follows: heat cramps, heat exhaustion, and then heat stroke. This process usually begins in hot weather with high humidity. People who are elderly and obese are at higher risk, as are individuals who take multiple medications (i.e., β-blockers, diuretics, neuroleptics, phenothiazines, or anticholinergics) or who consume excessive alcohol. Prolonged and excessive exercise and wearing tight-fitting clothing or too much clothing relative to the weather are also factors in heat-related illnesses. All phases of heat-related illness are emergency situations. If treatment is not administered immediately, the patient is at risk of death (

Dinarello and Gelfand 2005).

Neuroleptic malignant syndrome is an idiosyncratic, life-threatening complication of treatment with antipsychotic drugs that is characterized by fever, severe muscle rigidity, and autonomic and mental status changes (

Strawn et al. 2007). The signs of autonomic dysfunction in NMS include tachycardia, labile blood pressure, diaphoresis, vasoconstriction, and pallor. Signs of motor dysfunction include tremors, myoclonus, dystonia, dyskinesia, dysphagia, and dysarthria. Mental status changes can range from agitation to stupor to coma (

Delaney 2001;

Dinarello and Gelfand 2005).

Malignant hyperthermia is usually the result of inhaled anesthetics or the use of succinylcholine. Early recognition of malignant hyperthermia and its immediate treatment are essential for a patient’s survival. The cascade of events leading to malignant hyperthermia is rapid and may occur during or shortly after anesthesia has been administered (

Glahn et al. 2010).

Assessment and Management in Psychiatric Settings

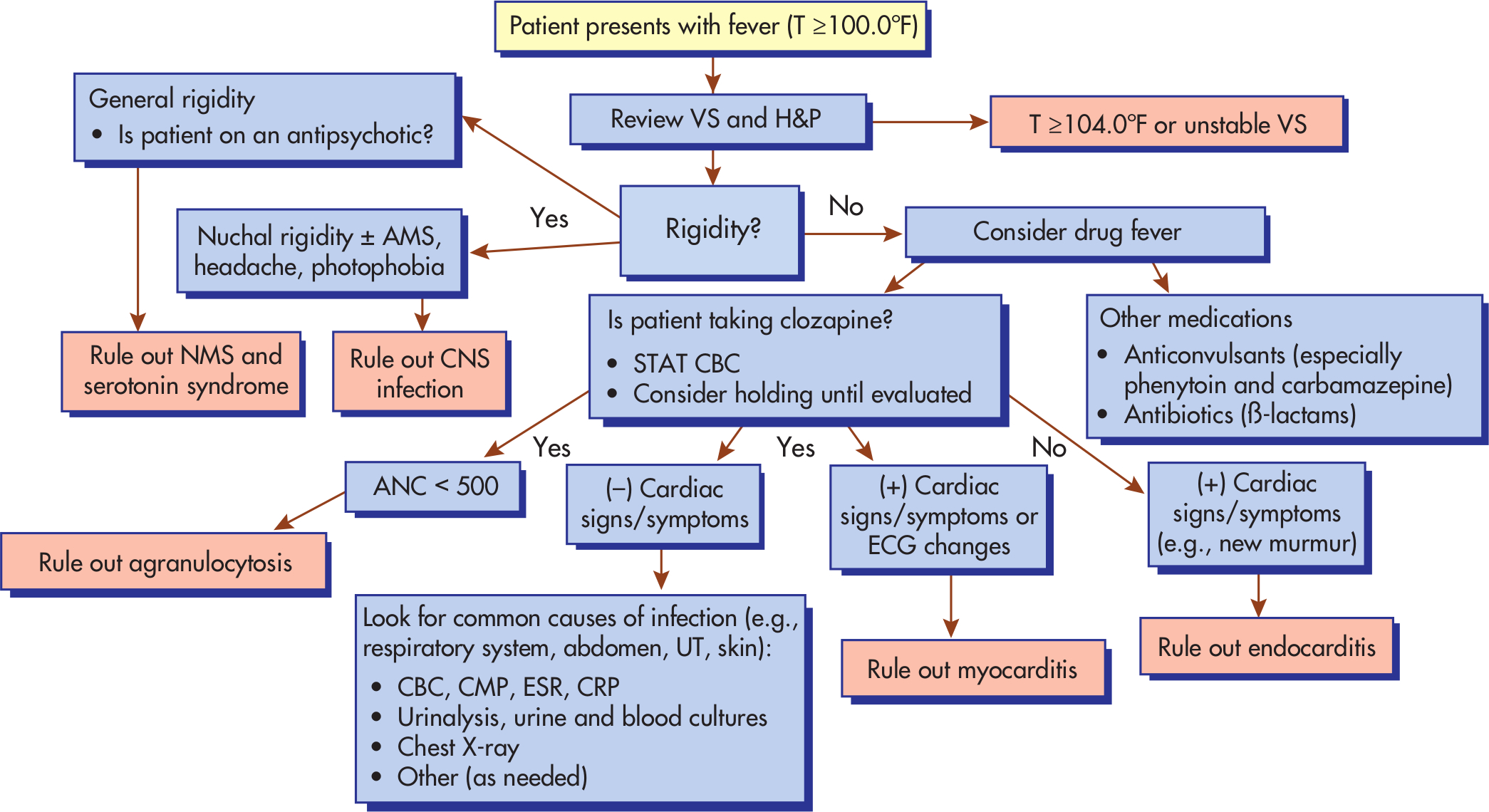

An algorithm that outlines the steps in assessment and management of fever is shown in

Figure 1–1. The approach is somewhat different in psychiatric settings because of the possibility of NMS and that of psychotropic drug–related fever, agranulocytosis, and myocarditis. In the majority of cases of fever, the etiology may be determined by means of a history and physical examination. Important historical facts are travel, social occupations, medication history, and social history. The timing and pattern of fever may add additional information. It is also important to ascertain the risk of serious illness in a patient according to his or her age or comorbid factors. The patient’s temperature, blood pressure, heart rate, respiratory rate, and pulse oximetry measurement must be obtained, and a finger-stick test and thorough physical examination must be performed. Basic laboratory tests—including complete blood count with differential, complete metabolic panel (including liver function tests), ESR, CRP, blood cultures, and urinalysis and urine cultures—should be conducted.

The need for ED referral and hospitalization will depend on the critical nature of the illness. A fever higher than 104°F (40°C) in any patient must be evaluated and treated in the ED. Patients who present with bacteremia or sepsis require hospitalization. In general, elderly patients, immunocompromised patients, and patients with comorbidities may require hospitalization. Patients for whom outpatient therapy failed also require hospitalization. Antipyretics should be given to the patient to address the fever, and antibiotics should be given if a bacterial infection is identified or suspected in high-risk patients.

Antipyretics do not affect the underlying illness but are given for the patient’s comfort while diagnostic testing is done to determine the etiology of the fever. For certain patients, such as those with temperatures higher than 104°F (40°C), aggressive treatment of fever is needed. Additionally, patients with myocardial ischemia, those predisposed to seizures, and pregnant women may require aggressive treatment with antipyretics because they may have increased complications and/or poor outcomes.

Key Points

•

Fever is a temporary increase in the body’s core temperature due to disease or illness.

•

Common causes of fever include infections, noninfectious inflammatory diseases, neoplasms, drugs, endocrine disorders, factitious disease, and hyperthermia.

•

Sepsis is a clinical syndrome in patients with suspected infection and requires prompt recognition and treatment.

•

Clozapine-induced fever may be a benign phenomenon, but caution should be taken to rule out infection and other serious side effects such as neuroleptic malignant syndrome, agranulocytosis, and myocarditis.

•

Patients receiving clozapine treatment should be monitored closely because they are at increased risk of infections and there may be a relationship between infection and elevated clozapine level with associated adverse events.

•

Febrile patients who are elderly, diabetic, immunocompromised, pregnant, or in a postoperative state should be evaluated and treated with high priority.

•

A thorough history and physical examination and basic laboratory tests are important steps in evaluation of fever.

Suggested Readings

Driver DI, Anvari AA, Peroutka CM, et al: Management of clozapine-induced fever in a child. Am J Psychiatry 171(4):398–402, 2014

Jamshidi N, Dawson A: The hot patient: acute drug-induced hyperthermia. Aust Prescr 42(1):24–28, 2019