Chapter 1. Pediatric Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Building a Collaborative Care Bridge to Pediatrics

Professional disciplinea | Roles | Comments |

|---|---|---|

Primary team members | ||

Attending physician | Leader of pediatric team Develops diagnostic formulation and treatment interventions Has final medical responsibility for patient | May have long-established relationships with patient and family Oriented toward immediate concerns of patient Potential for ambivalent feelings toward the consultant |

Resident | Frontline clinician involved in assessment and management Has trainee status as participant in residency training program | Short-term clinical rotations with lack of continuity Frequently dealing with time constraints and excessive burden of clinical work Lack of familiarity with role of the consultant |

Nurse | Implements bedside treatment interventions Provides education of patient and family Provides psychosocial support for patient and family Serves as liaison between family and pediatric team | Most frequent, direct contact Closest exposure to physical and emotional distress of the patient Lack of continuity due to shift changes and staffing issues |

Ancillary team members | ||

Physician (including psychiatrist) consultants | Consult to primary team to provide specialty input into patient’s care | May be part of primary team in integrated/colocated care models |

Social worker | Assists with basic social services for family Serves as liaison with outside agencies, including child protective agencies in cases of abuse and neglect Provides psychosocial support for patient and family Provides individual and family therapy Oversees referral to and coordination of outpatient services | May be part of primary team in integrated/colocated care models May have long-established relationship with patient and family Has established relationship with pediatric team Potential for “turf” issues with consultant due to overlap in clinical role |

Case manager | Coordinates resources and services inside facilities, outside facilities, and between care environments Works with patients, families, and other professionals to ensure proper resources and service utilization Serves as liaison with insurance companies for authorization of medical/behavioral health services | Generally, case manager is a nurse, although behavioral health support may fall to a social worker and/or a resource specialist |

Occupational and physical therapists | ||

Provides support with activities of daily living Oversees rehabilitation of patients after surgery and medical illness Provides treatment of feeding difficulties | ||

Nutritionist | Provides nutritional counseling and assists with calculation of caloric needs | Has an important role in treatment of patients with eating disorders and pediatric feeding disorders |

Child life specialist | Helps with coping with challenges of hospitalization, surgery, and disability | |

Coordinates hospital-based play and recreation services | ||

Chaplain | Provides spiritual assessment of patients and families | |

Provides psychosocial and religious support for patient and family | ||

Source. Adapted from Fritz 1993.

Roles of the Consultant

Assessment and Management

Referral Questions

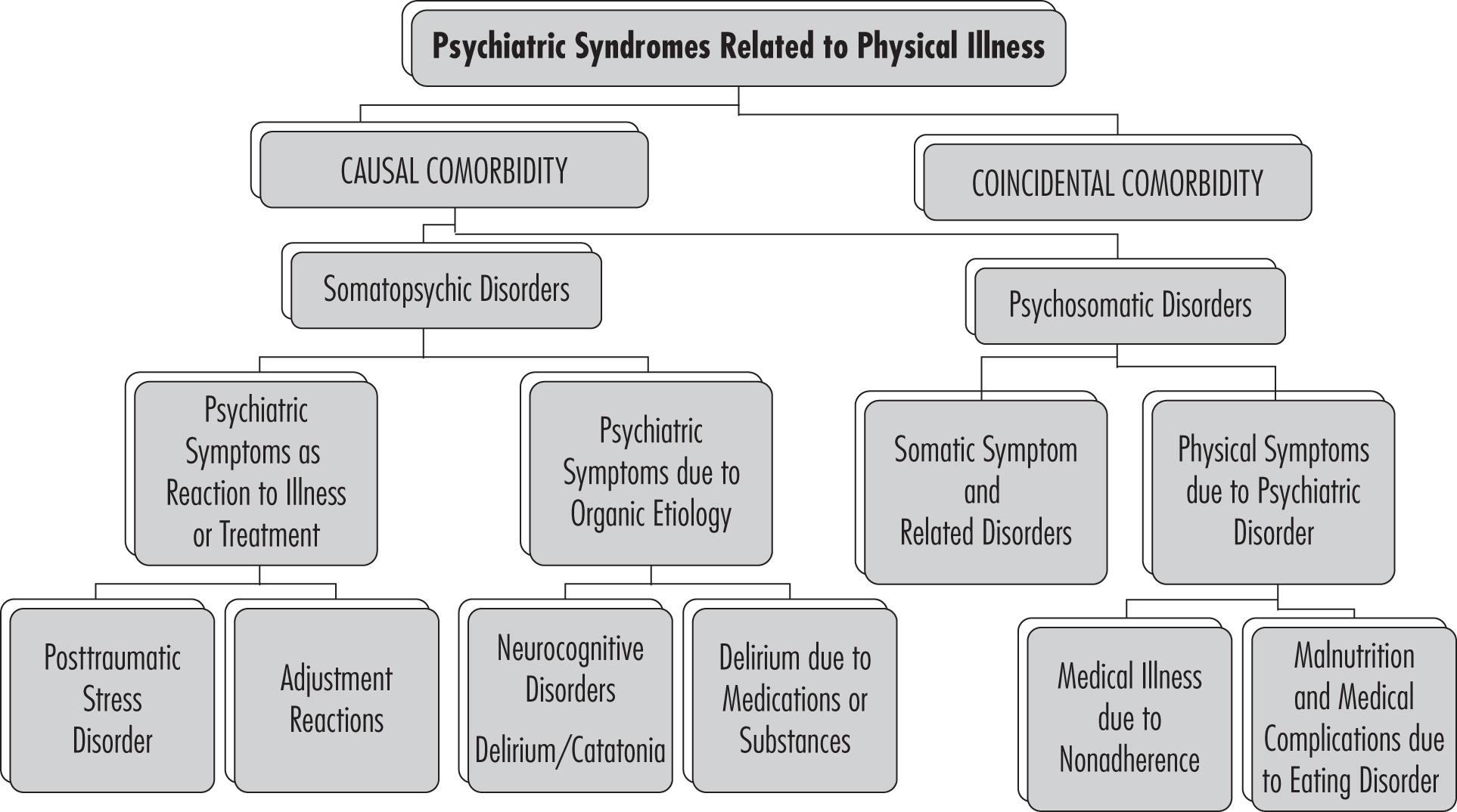

Classification Framework

Consultant Interventions

Patient and Family Advocacy

Liaison Activities With Pediatric Team

Clinical Innovation and Research

Practice Patterns in Pediatric Consultation-Liaison Psychiatry

Service Composition

Clinical Consultation Services

Service Demand

Service Funding and Challenges

Conclusion

References

Information & Authors

Information

Published In

History

Authors

Metrics & Citations

Metrics

Citations

If you have the appropriate software installed, you can download article citation data to the citation manager of your choice. Simply select your manager software from the list below and click Download.

For more information or tips please see 'Downloading to a citation manager' in the Help menu.

View Options

View options

PDF/EPUB

View PDF/EPUBLogin options

Already a subscriber? Access your subscription through your login credentials or your institution for full access to this article.

Personal login Institutional Login Open Athens loginNot a subscriber?

PsychiatryOnline subscription options offer access to the DSM-5-TR® library, books, journals, CME, and patient resources. This all-in-one virtual library provides psychiatrists and mental health professionals with key resources for diagnosis, treatment, research, and professional development.

Need more help? PsychiatryOnline Customer Service may be reached by emailing [email protected] or by calling 800-368-5777 (in the U.S.) or 703-907-7322 (outside the U.S.).