PSYCHOLOGICAL TRAUMA CAN OCCUR WHEN dire events affect individuals to the degree that they experience overwhelming fear, helplessness, horror, or a need to blot out feelings and memories. Memory fragments may not adequately contextualize the actual series of events. As a result, the potential to experience states of terror with a sense of helplessness and perceptual disorientation can live on in the mind after the conclusion of the original events.

At one extreme, denial may occur. At the other extreme, intrusive memories and fearful expectations may cause social dysfunction. The self and the world may appear to have changed, and the person may report depersonalization and derealization experiences. Subsequently, the patient may experience physical health consequences such as exacerbation of preexisting medical conditions or gastrointestinal and cardiovascular symptoms (

Croft et al. 2019;

Kessler et al. 2018). Certain brain modules, circuitries, and hormonal neurotransmitter systems may be sensitized to alarm reactions or disrupted control (

LeDoux and Pine 2016;

Lehner et al. 2016).

Stress response syndromes may be diagnosed when the aforementioned denial and intrusion states of mind do not subside with time and support. The aim of treatment is both to restore equilibrium and advance coping capacities. An important aspect of treatment is support for restoration of equilibrium through reduction of entry into states of emotional turbulence.

Various degrees of cognitive processing of the meanings of the events and the consequences to the self may occur in phases (see section “Phases of Response to Traumas and Losses”). In this book, I emphasize that psychotherapy can assist individuals in making such restorative changes. In addition to symptom relief, attitudes formed during a process of working through can lead to more self-efficacy and enhanced emotional regulation. The treatment of an impacted person may help that individual achieve personality growth (

Horowitz 2016,

2019).

Memories of Trauma and Loss Events

Incompletely assimilated memories are retained in various strata and categories of storage. The intensity of potential meanings and feelings associated with the events can mark some memories for later conscious representation, review, and reappraisal. The potential for unthinking rage, anxiety, shame, guilt, and prolonged sadness may remain until the completion of that processing.

Disturbances in identity, relationships, and emotional regulation may occur and may undergo phases of resolution or return. Social connection may be disrupted just when the impacted person needs more support. Self-esteem may collapse, and self-coherence may falter.

Stress response syndromes may include a sense of being unable to rely on one’s previously learned capacities for how to solve current problems. The mismatch between the trauma and the coping skills that previously had been effective may lead to self-criticisms and blaming. Loss of coherence in self-organizing beliefs may contribute to dissociative experiences.

Extreme affective potentials may continue as disturbed states of mind. The person may have attacks of confusion, rage, or despair. An individual may experience a sense of loss of control over feelings just when he or she needs heightened capacity to regulate emotions. However, with successful assimilation and accommodation, memory systems can be integrated, and a coherent sense of past, present, and future can be achieved.

Avoidance Symptoms

Emotional blunting and dissociative states can alter patterns of social interaction. The individual may develop phobic avoidance of places and situations that remind him or her of the trauma, even inhibiting exposure to colors and odors associated with the trauma. Socially, members of an individual’s support network may take offense with what appears to them as withdrawal due to numbing of feelings and avoidance of previous levels of warm connections. Family life, friendships, and work relationships may deteriorate. If this happens, others’ withdrawal may limit support and repair of the individual’s sense of coherent self-organization.

Intrusive Symptoms

Memories tend to repeat in conscious representation in spite of avoidance maneuvers. Intrusive experiences include nightmares, bad daydreams, flashbacks, perceptual memories, and frightening expectations of “What’s next?!” Recurrent cycles of avoidance and intrusive states of mind are common (

Horowitz 1976,

2011;

Horowitz et al. 1979). Processing takes longer than most people expect. For example, when in someone is mourning, it may take a year or more before the individual feels that a new equilibrium is in place.

Individuals may maintain hyperalert attention deployment as if they were in perpetual danger even though they are not in danger. Compulsive behavioral reenactments may occur. For example, after an assault, an individual may provoke a fight with a stranger or assume the role of an aggressor instead of a victim.

Recurrent intrusive memories and imaginary elaborations can range from a minor fragment of the traumatic perceptual experience (such as a flashback to a single smell or image) or a larger complex of experiences (such as seemingly reliving a sequence of events). They can also take the form of the individual compulsively engaging in risky behavior as if to prove to himself or herself that the trauma or loss cannot recur. Intrusive trauma memories may also include imagined scenarios of what the individual wishes he or she had been able to do or would want to do should a similar event ever happen again.

Cognitive Processing

In nonpathological reactions to stressor events, individuals can expect to see a decrease of intrusive, avoidance, and alarm states of mind over time. This is due to a combination of automatic mental processes that include habituation (getting used to the safety of a somewhat similar situation in which the threat does not repeat), extinction learning (learning that the perceptual stimuli associated with the trauma are no longer associated with traumatic probabilities), and desensitization (the body learning to remain calm in similar perceptual situations).

In psychopathological syndromes, alarmed reactions in response to trauma-associated percepts may be intense, frequent, and prolonged. For example, a person mugged in a dark garage may feel his or her heart race and stomach clench when driving into the same garage years later or even any dark place with cars. The goal of adaptation is the controlled review of experiences with cognitive reappraisals until acceptance occurs, coping strategies are fully mobilized, and new schemas are formed. The revised schematization affects the person’s sense of identity and connectivities to significant others as well as beliefs about attachments to social communities.

Reactions to stressor events can take several forms. Clinicians should look for the five Ds: dissociation, disavowal, denial, depersonalization, and derealization. Dissociation can reduce terror by effectively telling one’s mind, “I am not really here.” Disavowal of aspects of traumatic experiences can be used to lessen negative emotions that otherwise threaten to disorganize thought. Denial can include misappraisal of the meanings of the event. Depersonalization can be a sense of no longer being the same person as before the event, and derealization can be a sense that current perceptual reality is unreal or somehow dreamy. The five D experiences are maladaptive and distressing when the individual reflects on them, but they are part of defensive coping because emotional flooding may be reduced for a time.

Phases of Response to Traumas and Losses

Patients often seek a first clinical evaluation long after the conclusion of a stressor event and perhaps midway in the phases of reaction. The prototypical phases of reactions after a stressor include the following (

Horowitz 2011):

•

Outcry—The first emotional response is often intense and uncontrolled.

•

Denial, numbing, and avoidance—Excessive emotional regulation strategies may be used in the phase that follows initial emotional expressions.

•

Intrusions, pangs, and repetitions—Memories of and associations with conscious representations emerge, giving rise to more sorrow, anger, remorse, or fear than was felt in the previous phase of denial and numbing.

•

Working through—The trauma story is renarrated, the meaning of the trauma to the self is reappraised, and attitudes are revised. Swings between intrusion and avoidance may occur and gradually attenuate as new coping skills are acquired.

•

Restoration of equilibrium—A person who has regressed under stress may progress to a pre-event level of functioning. Some people may exhibit an increase in self-coherence, self-esteem, and confidence as signs of posttraumatic personality growth (

Horowitz 2016).

These general phases of stress response syndromes may seem similar to the five stages of grief described by

Kübler-Ross (1969) as denial, anger, bargaining, depression, and acceptance. However, control of thought and regulation of emotion are emphasized in the phases of reaction of stress response syndromes, whereas the ideational and emotional content is emphasized in the progression through the Kübler-Ross stages of resolving grief. In addition, in psychotherapy, patients move in and out of the different phases of stress response syndromes, and each of these phases is worked through while taking into account the patient’s preferences, cultural beliefs, and social supports.

Personality Factors

Individuals experience trauma in terms of their prior life experiences and personality characteristics. Appraisals and reappraisals are influenced by patients’ identity and schematic structure of relationships between self and various others, including ethnic and spiritual communities. In addition, their experience of prior stressor events will have left enduring and only slowly changing attitudes. Adverse childhood events may have inscribed a sense of excessive vulnerability (

Caspi and Moffitt 2018;

Herman 1997;

Horowitz 2002). These are reasons why recovery from trauma often involves reorganizing narratives about the self in the world in the time frames of past, present, and future (

Classen et al. 2006;

Cloitre et al. 2009).

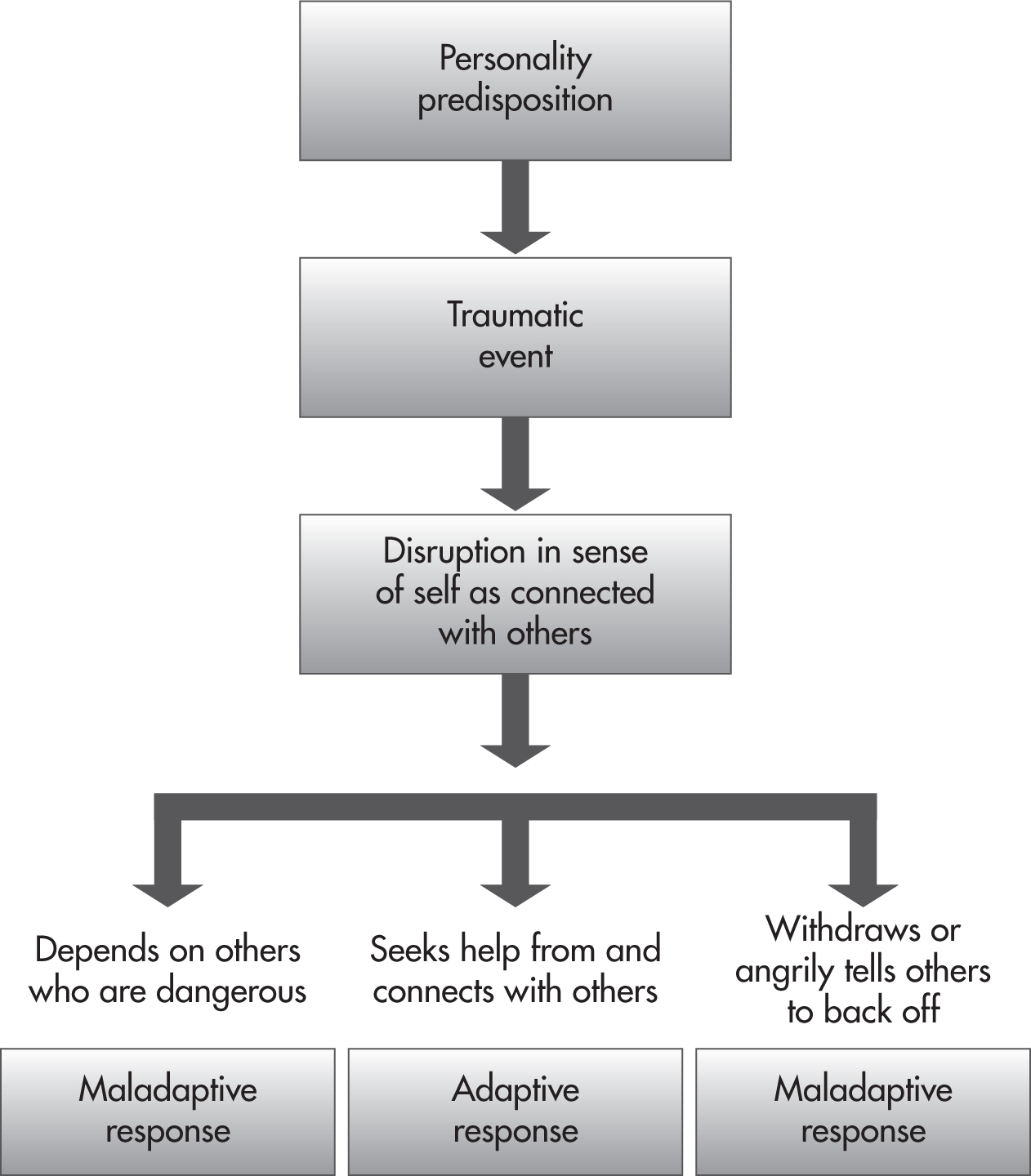

Schemas for relationships develop throughout life and build toward wisdom with life experiences. Various personality configurations can lead to adaptive responses to trauma and loss, such as seeking help and building self-supportive connections with others. Preexisting personality problems can lead to maladaptive responses, as shown in

Figure 1–1. The individual may seek risky, exploitative supports for self-coherence or react too negatively to possible helpers.

The next case example illustrates how a stressor event can become entangled with preexisting personality issues.

Pathological Syndromes

Treatment stages are described in this book in terms of syndromes that are simple, comorbid, or complex.

Table 1–1 depicts these typologies.

Treatment

Psychotherapy is an effective treatment for stress response syndromes. The patient in psychotherapy goes through various phases of change, and the therapist uses various teachings in each phase. These phases are described in the ensuing chapters and are summarized in

Table 1–2. Formulation and therapy techniques are typically revised as the treatment proceeds.

Summary

Stress response syndromes are characterized by intrusive mental experiences and avoidant behaviors with psychological numbing and inhibitory operations. These signs and symptoms may be prolonged in individuals who have comorbid conditions or predisposing complications from personality configurations. The use of phase-oriented therapy techniques and individualized formulations will lead to symptom amelioration and even personality growth. The goals of treatment are providing sufficient support, helping cognitive and emotional processing, and providing ways to learn how to enhance capacities for coping and reflective reasoning.