Menopause

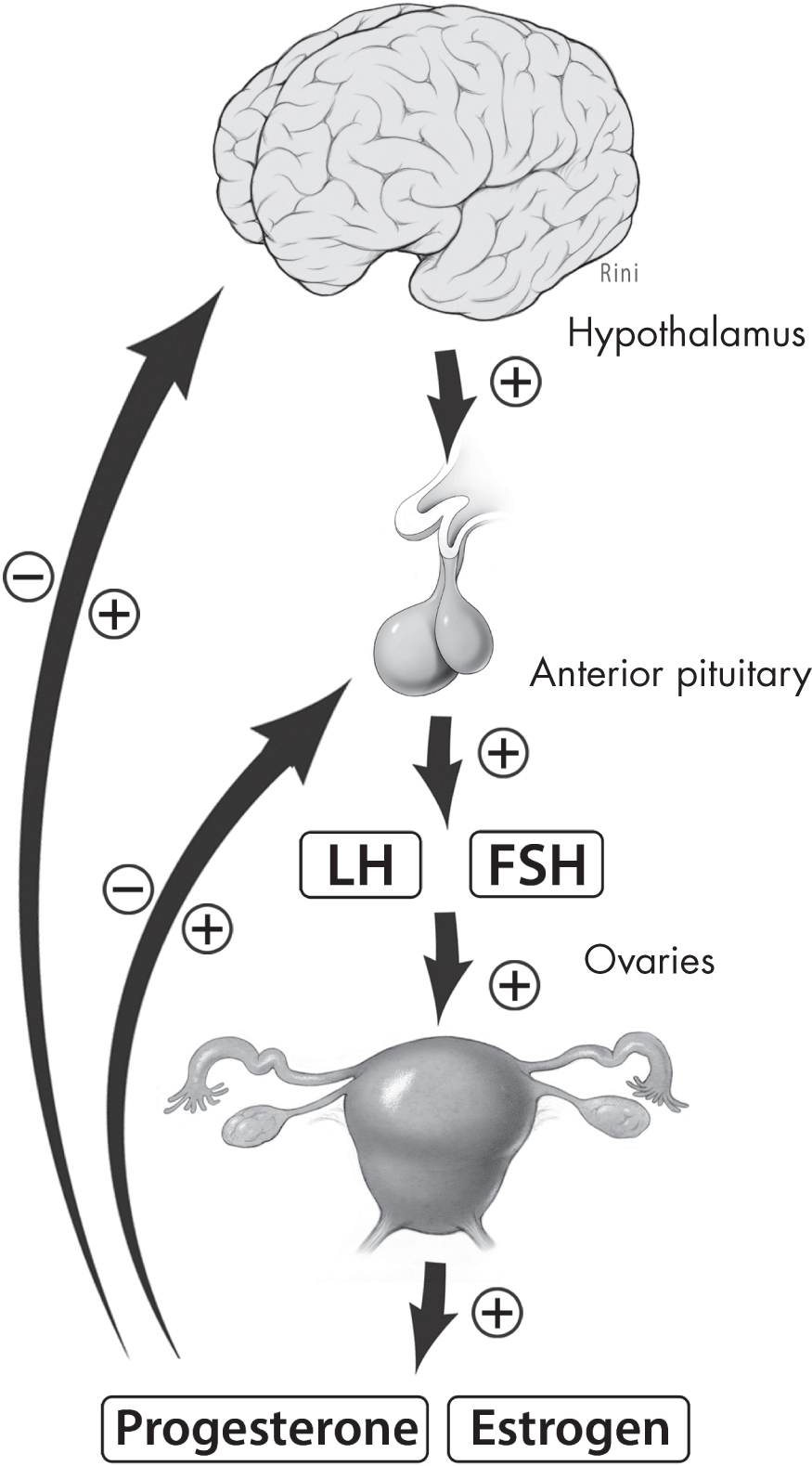

Menopause is defined as the absence of menstrual periods for a full year, and it is caused by reduced secretion of ovarian hormones, including estrogen and progesterone (

Bacon 2017). An estimated 1 billion women worldwide have experienced menopause (

Hoga et al. 2015). The average age of menopause in the United States is 51.5 years (

Hoffman et al. 2020).

Menopause is a normal event for women and generally signals the end of a woman’s reproductive capacity. It may be experienced as a liberating end to anxieties about childbirth and to discomfort related to one’s reproductive life, or it may be viewed negatively—particularly in Western cultures—through its association with aging (

Minkin 2019). (Some women might experience a combination or neither of these reactions.) Individual experiences of menopause vary, and at times women will seek medical or mental health attention for the management of symptoms (

Nelson 2008). In this section, we review the physiology of the menopausal transition. See

Chapter 7, “Perimenopause,” for a review of the relationship between the menopausal transition and mental health.

Menopause can be a naturally occurring event, or it can be brought about either medically or surgically as a result of—or for the prevention of—disease. Medical menopause is beyond the scope of this chapter, but it is worth noting that women with medical or surgical menopause, particularly prior to age 45 years, may have more severe and prolonged menopausal symptoms (

Rodriguez and Shoupe 2015). In addition, women experiencing medical menopause have an increased risk of depression, heart disease, osteopenia or osteoporosis, sexual dysfunction, and cognitive decline compared with women in the general population (

Rodriguez and Shoupe 2015).

The menopausal transition has several phases: perimenopause, menopause, and postmenopause.

Perimenopause, characterized by estrogen decline and irregular menstrual cycle length, is the interval of time preceding the onset of menopause (

Dutton and Rymer 2015). On average, perimenopause begins 4 years prior to the final menstrual cycle—on average, age 47—and lasts for several years (

Hoffman et al. 2020).

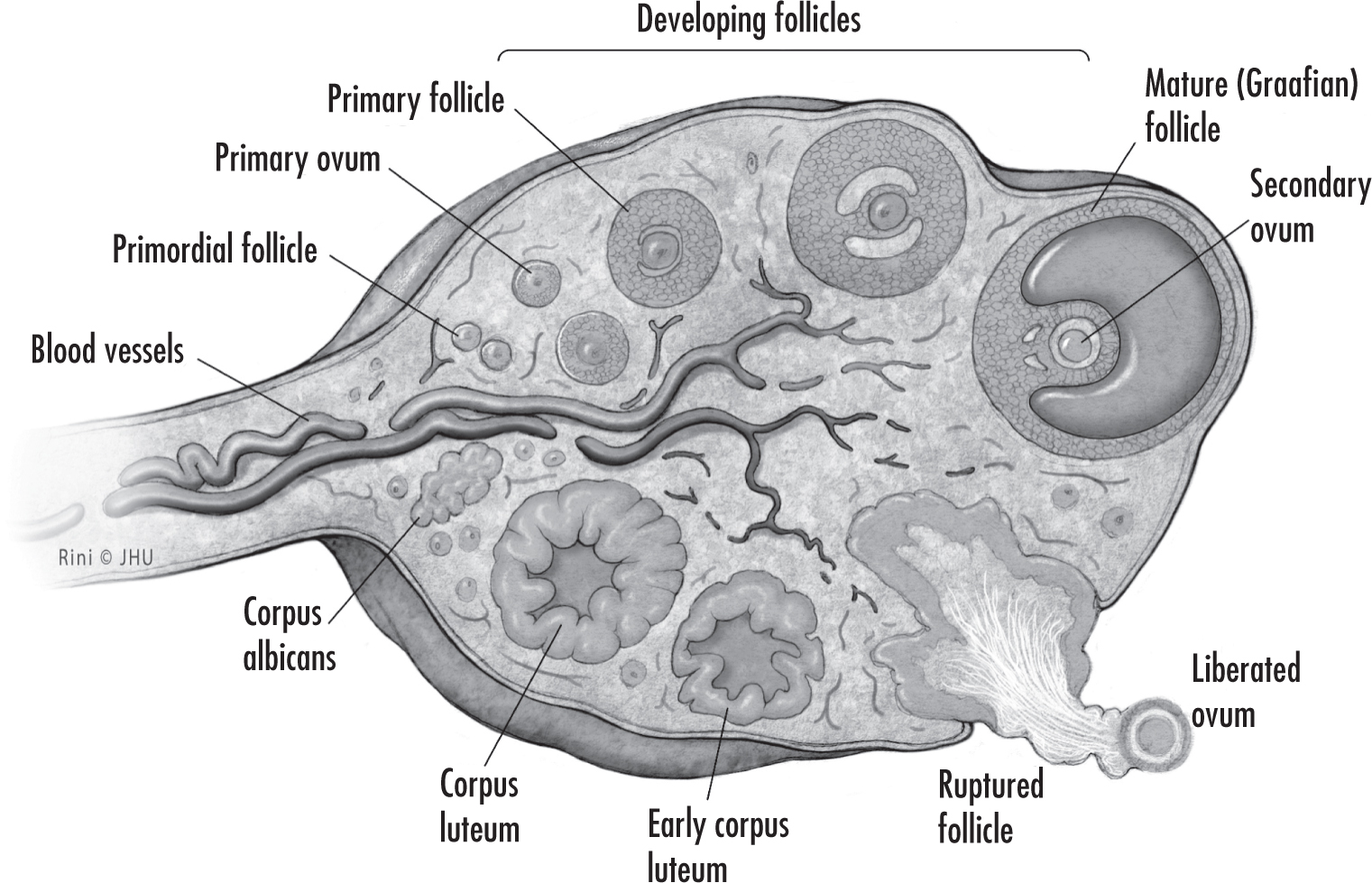

Menopause reflects the process of ovarian follicular depletion. Ovarian senescence begins in utero with programmed oocyte atresia and then continues after birth by way of follicular maturation and regression (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Beginning in a woman’s later 30s to early 40s, ovarian follicles are depleted at a more rapid rate until the eventual loss of ovarian activity by the time menopause is reached; loss of ovarian function before age 40 is termed

premature ovarian insufficiency (

Hoffman et al. 2020).

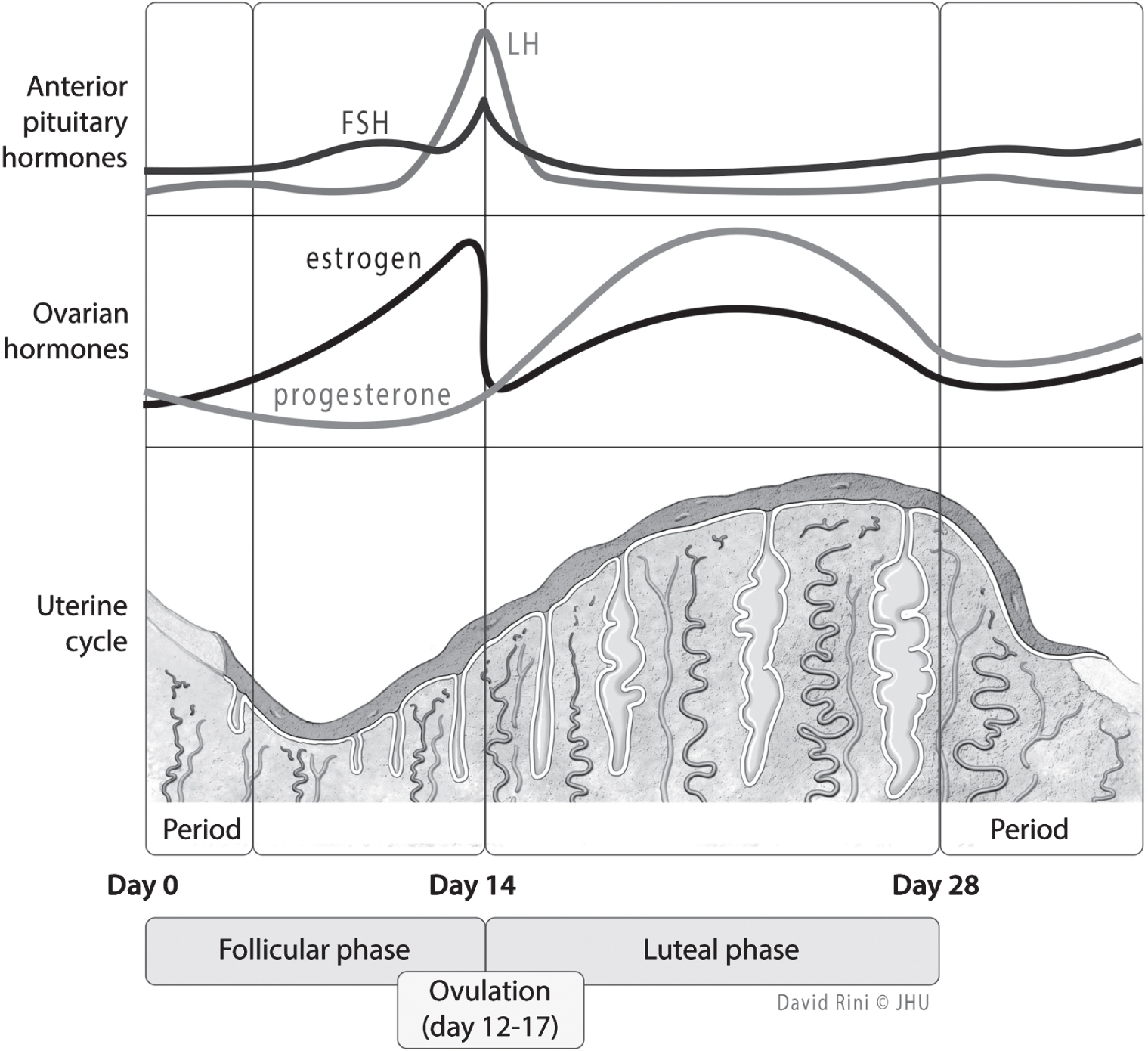

In the early perimenopausal transition stage, the length of time between menstrual cycles increases from the typical 25–35 days during reproductive years to approximately 40–50 days (

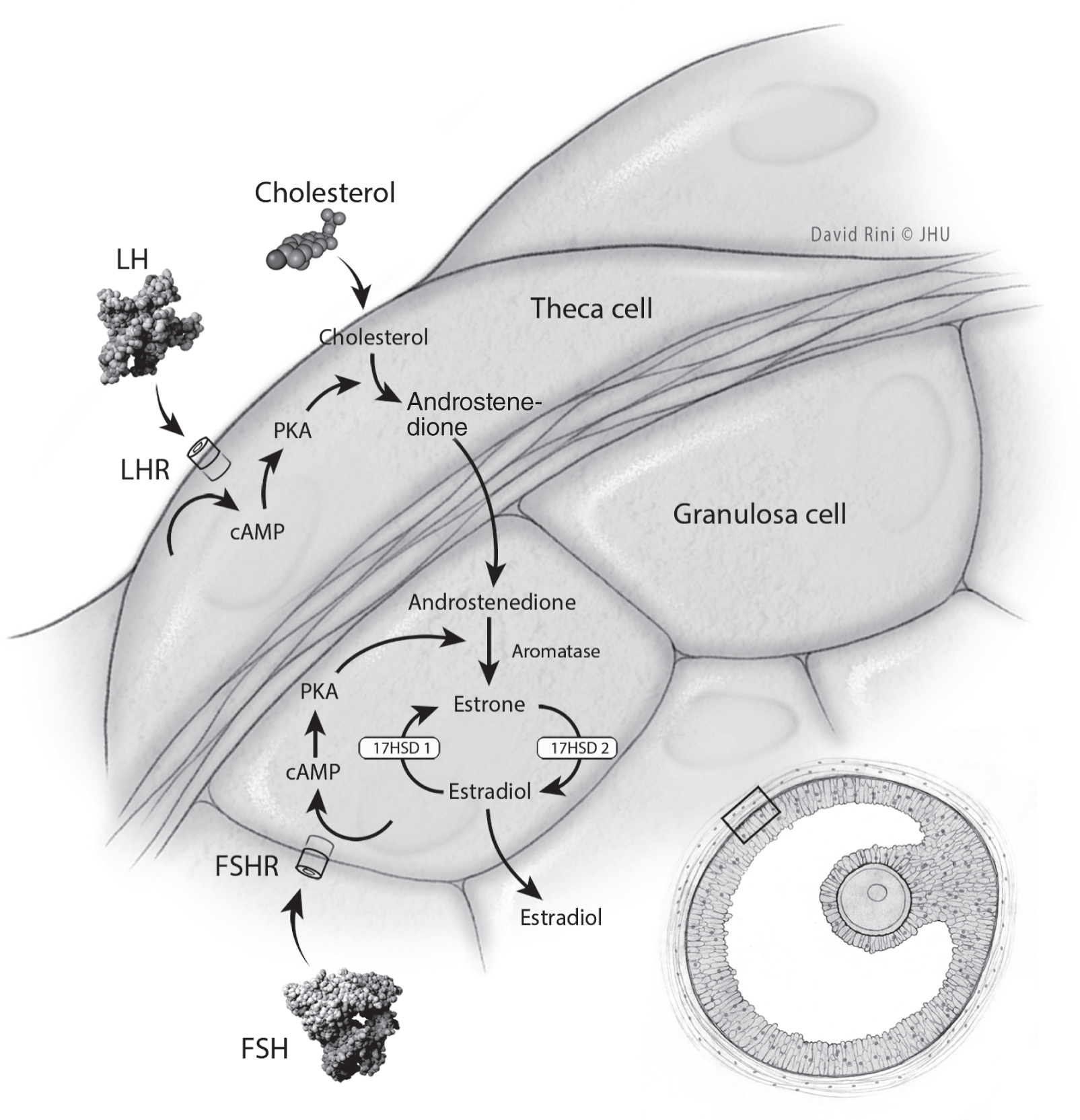

Dutton and Rymer 2015). During this time, FSH levels vary, but generally this hormone is on the rise. Estradiol levels are initially maintained steadily or, like FSH levels, are increased (

Dutton and Rymer 2015). Such changes reflect diminished ovarian reserve: fewer follicles are present to secrete inhibin, a hormone that exerts negative feedback on FSH secretion (

Dutton and Rymer 2015;

Hoffman et al. 2020). Initially, increased FSH levels result in greater follicle recruitment and therefore an increase in estradiol; this transition period correlates with a variability in menstrual cycle length, increased amenorrhea, and more frequent anovulatory cycles (

Dutton and Rymer 2015). Eventually, cycle lengths shorten and anovulatory cycles become more frequent, although unpredictably so (

Hoffman et al. 2020). In addition to changes in estrogen levels, progesterone levels start to decline (

Hoffman et al. 2020). As the perimenopausal period progresses and menopause is reached, FSH continues to rise and estradiol levels fall, whereas in the postmenopausal period, FSH and estradiol levels initially stabilize and eventually both decline (

Dutton and Rymer 2015).

The most common physical symptom of menopause is the development of hot flashes, reported by up to 50% of menopausal women (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Classically, hot flashes last 2–4 minutes and are described as a sudden sensation of heat beginning on the chest and face and then progressively spreading throughout the body. They can occur several times in a day and can be associated with perspiration, palpitations, chills, anxiety, and irritability (

Hoffman et al. 2020). The proposed physiology surrounding both hot flashes and night sweats (vasomotor symptoms) reported by menopausal women is related to changes in central thermoregulatory functioning due to decreased estradiol (

Dutton and Rymer 2015). Skin temperatures can increase, particularly in the fingers and toes, due to peripheral vasodilation, whereas core temperatures may slightly decrease (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Recent studies estimate that hot flashes last for 7 years on average (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Significant differences in the prevalence of vasomotor symptoms in women of different racial backgrounds have been reported, with Black women experiencing the highest prevalence and longest duration of all groups studied (

El Khoudary et al. 2019).

Additional symptoms noted during menopause include vaginal dryness and an increase in urinary tract infections, which are functions of decreased estradiol and progesterone in the urogenital tract (

Dutton and Rymer 2015). Specifically, depleted estrogen levels lead to the thinning of the epithelial lining of the vagina and subsequently, in the long term, to vaginal atrophy (the vagina shortens, narrows, and becomes less flexible) (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Women may first notice a decline in vaginal lubrication during sexual activity; however, as the decreased estrogen state progresses, discomfort may be noticed during daily activities. Vaginal dryness and associated discomfort are likely among several factors in the decreased sexual function associated with menopause. Studies have shown racial differences in postmenopausal sexual functioning; compared with white women, Asian women report lower sexual desire and lower importance of sex, and Black women report lower levels of arousal and greater importance of sex (

El Khoudary et al. 2019).

Estrogen depletion can also affect other organ systems and can be associated with cardiovascular disease, metabolic syndromes, and osteopenia or osteoporosis. Estrogen deficiency is proposed to play a role in the increased risk of cardiovascular disease after menopause and may be impacted in part by shifts in lipid profiles during perimenopause (

Derby et al. 2009). There are also proposed shifts in body composition in the postmenopausal period, including increased fat content and decreased lean muscle. In terms of bone health, it is postulated that decreased estrogen levels lead to excessive bone resorption (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Ultimately, this results in osteopenia (a condition that occurs when the body does not make new bone as quickly as it reabsorbs old bone), which is the precursor to osteoporosis, a progressive reduction in bone mass and strength that contributes to fractures (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Approximately 40%–50% of postmenopausal women will experience a fracture related to osteoporosis in their lifetime (

Hoffman et al. 2020). Racial differences in postmenopausal fractures have been described—rates among Black and Asian women are approximately half of those in white women—however, the physiological differences that underlie this pattern are not well understood (

El Khoudary et al. 2019). For a detailed discussion of these clinical features and their relationship to mental health, see

Chapter 7, “Perimenopause.”