ETHICS AND PROFESSIONS

Ethics is a formal branch of philosophy that examines, evaluates, and seeks to more deeply understand the moral aspects (the right and wrong) of human nature and action. Within the profession of medicine, ethics has become an applied discipline, with a basis in emerging evidence as well as in historical concepts that have endured and evolved over many centuries. The fields of clinical and research ethics encompass the principles, virtues, values, decision-making approaches, accepted and expected behaviors, and rules of conduct that are fundamental to the modern profession of medicine, and the biomedical sciences, in our society.

A profession is a set of individuals who possess a distinct expertise and have been entrusted to serve a special role, with specific obligations, rights, and privileges (

Roberts 2016). A central commitment of a profession is to ensure that its members possess specialized knowledge and skills and that these are used to fulfill the positive role of the profession in society. In the profession of medicine, members are concerned with activities in support of the societal aim of promoting health and diminishing disease and suffering. This is a diverse endeavor that includes engaging in the practical work of clinical care and biomedical research—generating new knowledge through inquiry; imparting expertise (both cognitive and technical skill) across the field and to the next generation of professionals; evaluating the competence of professionals and professionals in training (e.g., through specialty examinations and licensure standards); providing leadership and advocacy—and recognizing, remediating, or rooting out members who are not capable of acting or, irrespective of ability, who do not act in accordance with the expectations of the field. The vitality and legitimacy of a profession rely on cultivating a membership that reflects the broader makeup of society, appointing members of marginalized groups to positions of leadership, and detecting and reducing bias and inequity through continual, honest, and robust self-analysis.

A profession itself has moral importance because of the trust and privileges conferred on it by society as a whole. Being a member of a profession has moral standing because society requires that professionals possess certain qualities and adhere to a specific set of duties. The reasons for this are self-evident: a surgeon may cut another person with a knife so long as he possesses appropriate expertise and his intent is to help the patient or to lessen the patient’s suffering. This is true even at times when consent is not possible (e.g., an unconscious trauma victim) and even if there is a poor outcome not due to negligence. Under nearly all other imaginable circumstances in everyday life, cutting another person with a knife would be considered assault. Similarly, in the course of psychotherapy, a psychologist may learn of the most deeply held private thoughts of a patient, including suicidal or homicidal fantasies or intended unlawful behavior; the psychologist in this situation is entrusted with preserving the confidentiality of the patient unless the patient expresses a specific and immediate threat to another person. A consultation-liaison psychiatrist may assess the decisional capacity of a seriously ill patient and determine that he or she is not able to decline recommended treatment. The psychiatrist, furthermore, may under certain circumstances insist that the patient undergo treatment, for example, be hospitalized or given medications against his or her preferences. These violations of the liberty of another person would not be tolerated in society under nearly all other circumstances. These violations are only tolerated because of the expectation of absolute adherence to the moral underpinnings of the profession in support of societal goals. In this case, the psychiatrist is assumed to be acting in service toward the well-being of the patient.

Medical professionals are expected to act according to an integrated set of values such as beneficence and justice and to demonstrate trustworthiness repeatedly and consistently. Distinct professional behaviors are generative of distinct types of trust, all of which are necessary in professional formation (

McCullough et al. 2020). Intellectual trust, the commitment to scientific and clinical excellence, is generated by patients’ confidence that clinicians are competent in diagnosing and treating their conditions, with mastery of the vocabulary and reasoning methods of their field. Intellectual trust also requires that patients actively rely on clinical competence. Moral trust is generated through the systematic privileging of the health-related interests of patients over the self-interests of organizations. Forms of organizational self-interest, such as financial incentives, may be necessary but must be kept secondary to patient interests. Moral trust also requires that patients rely on health professions’ moral commitments. Both intellectual and moral trust, therefore, are sustained ultimately through their utility as perceived by patients rather than by the belief or conceptual agreement of an organization.

Clinical medical ethics refers to the integration of ethical considerations into everyday medical practice (

Siegler 2017). Health professionals may apply ethical concepts in practice without being aware that they are doing so (

Siegler 2017). All health professionals have professional, legal, and personal obligations to apply ethics standards in their care of patients (see

Table 1–1).

PROFESSIONALISM

Professionalism is notoriously difficult to define, a fact that is highlighted by the numerous and evolving ways in which it has been characterized (see

Table 1–2). Standards of professionalism vary among medical specialties, and perceptions of what constitutes professional behavior are inconsistent (

Dilday et al. 2018;

Dubbai et al. 2019;

Hendelman and Byszewski 2014;

Hoonpongsimanont et al. 2018). Professionalism might be defined as the quality of being faithful to the goals of the profession, which in medicine is predicated on honoring a number of ethical obligations as well as embodying competence and exhibiting sensitivity to cultural values. A cardinal feature of professionalism is a willing acceptance of an ethical obligation to place the patient’s and society’s interests above one’s own (

Stobo and Blank 1994). Some conceptualizations of professionalism emphasize upholding the trust of patients and the public and the application of virtue to the practice of medicine (

Brody and Doukas 2014). Professionalism also encompasses the socialization of emerging professionals (e.g., during training), who learn, absorb, and emulate the aims, qualities, and behaviors that characterize the profession (

Koch 2019).

The traditional literature has outlined three distinct approaches to defining and understanding professionalism. The first identifies and lists specific elements and behaviors, the second delineates principles that guide behavior, and the third organizes these elements and principles into rubrics or themes (

Table 1–3). Regardless of the taxonomy, all of the conceptual labors surrounding professionalism trace back to the Hippocratic writings, particularly the convictions of beneficence and nonmaleficence: “. . . as to diseases make a habit of two things, to help or at least to do no harm” (cited in

Siegler 2002, p. 409).

The American Academy of Pediatrics developed one early model of professionalism, which included eight components (

Klein et al. 2003): honesty/integrity; reliability/responsibility; respect for others; compassion/empathy; self-improvement; self-awareness/knowledge of limits; communication/collaboration; and altruism/advocacy. Specific manifestations of these components include “is truthful with patients, peers and in professional work” and “puts best interest of the patient above self-interest.”

A principle-based approach, the second model, evolves from the bioethical standards of beneficence, autonomy, nonmaleficence, and justice. The concept of justice is relatively recent and focuses attention on the distribution of and access to resources within a defined community.

In 2006, the American Medical Association Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs added a principle addressing this issue: “A physician shall support access to medical care for all patients” (p. lvii). Ethicists have added two additional principles to the bioethical model. Veracity is the principle of telling the truth, and fidelity is the principle of faithfully serving a patient or a positive objective (

Beauchamp and Childress 2001;

Roberts 2016). The

American Psychological Association (2017) has five principles that parallel these two additional principles: beneficence and nonmaleficence; fidelity and responsibility; integrity; justice; and respect for people’s rights and dignity.

Several theorists have analyzed the literature and clustered the various elements and principles into distinct themes, following the third model.

Jha and colleagues (2006) differentiate seven themes that capture the concepts and behaviors of professionalism: compliance to values (e.g., maintaining confidentiality); patient access (e.g., providing continuity of care); doctor-patient relationship (e.g., treating patients with respect); demeanor (e.g., being courteous and polite); management (e.g., working in a team); personal awareness (e.g., auditing one’s own practice); and motivation (e.g., protecting patients’ interests).

Van de Camp et al. (2004) elegantly distilled professionalism into three rubrics: interpersonal, public, and intrapersonal. Interpersonal professionalism pertains to a health care provider’s relationships and interactions with patients and other health care providers. Subsumed under this rubric are such concepts as altruism, honesty, compassion, appropriate use of power, shared decision-making with patients, and sensitivity to diverse populations. Public professionalism relates to fulfilling the demands that society places on the medical profession and involves elements including adherence to an ethical code, technical competence, and enhancing the welfare of the community. Intrapersonal professionalism concerns the responsibility of the individual to maintain the ability to function in the medical profession; specific responsibilities include lifelong learning, self-awareness, absence of impairment, and knowledge of limits.

The delineation of professionalism into the three rubrics of interpersonal, public, and intrapersonal professionalism is particularly pertinent to the interdisciplinary practice of mental health (

Table 1–4). Individuals who receive psychotherapeutic services place themselves in a vulnerable situation by allowing another individual to observe and evaluate their emotions, cognitions, attitudes, values, and behaviors. Mental health clinicians are expected to facilitate the growth and development of these individuals. This responsibility requires the valuing of the patient’s autonomy and integrity, respect for the patient-clinician relationship and boundaries, appreciation of power differentials, continuous focus on the needs of the patient, and sensitivity to cultural diversity and the ecological context in which patients live and function. This is especially difficult when the patient is overwhelmed by life’s predicaments and is experiencing despair, has a disabling psychiatric illness, or has been ordered by a court to receive treatment.

Interpersonal professionalism is also applicable to interactions with colleagues and other providers. Because patients function within an ecological environment, clinicians regularly coordinate care with an array of other providers, including other medical specialists, nurses, case managers, legal personnel, and advocates. This collaboration is critical for the delivery of optimal care to the patient. Another vital component to optimal care is a clinician’s ability to recognize and address ethical lapses or professional impairment in colleagues.

Public professionalism pertains to advancing the access of care to individuals with mental health problems and to populations that are typically underserved. The

New Freedom Commission on Mental Health (2003) denoted several goals that can transform mental health care: 1) to view mental health as essential to overall health; 2) to provide early mental health screening and treatment in multiple settings; 3) to eliminate disparities in services; 4) to deliver excellent care that is research based; and 5) to use information technology to improve care. Public professionalism also involves working toward the destigmatization of mental illness, creating parity in the allocation of resources between mental health and other health care, and negotiating with managed care and other social institutions to create systems of care that meet the goals of the New Freedom Commission on Mental Health.

Education is a key element of public professionalism. Senior clinicians have an obligation to teach, mentor, and act as role models of professionalism to their residents and junior colleagues. Professionals also have a responsibility to educate medical colleagues, administrators, and their communities about such issues as the relationship of mental health to physical health, lifestyle decisions (e.g., diet), and stress management.

Intrapersonal professionalism is especially relevant for mental health practitioners. Clinicians are responsible for their own self-awareness, self-care, and self-growth. Decades ago,

Bugental (1965) observed that psychotherapists need to have humility, a growth orientation, fascination with psychological processes, and an evolving set of constructs related to the self, the world, therapeutic processes, and personality. Mental health professionals cannot effectively treat their patients unless they care for themselves.

Internal medicine specialists created a charter that summarizes the concept of medical professionalism in the following way:

Professionalism is the basis of medicine’s contract with society. It demands placing the interests of patients above those of the physician, setting and maintaining standards of competence and integrity, and providing expert advice on matters of health. The principles and responsibilities of medical professionalism must be clearly understood by both the profession and society. Essential to this contract is public trust in physicians, which depends on the integrity of both individual physicians and the whole profession. (

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation et al. 2002, p. 244)

Professionalism is a multidimensional concept that encompasses ethics; relationships with one’s patients, colleagues, and community; public policy; and self-awareness.

Evaluating professionalism is extraordinarily challenging and has evolved. In the mid-1980s, a holistic concept of professionalism began to complement terms such as clinical competence in discourse about medical training. Professional boards such as the American Board of Internal Medicine (ABIM) began to add new professional attributes, such as humanistic qualities, to their concepts of ideal clinical behavior. Rapid financial and structural changes in health care resulted in an alarming increase in novel ethical challenges that were increasingly understood to be inadequately addressed in medical training.

In 1990, the ABIM began Project Professionalism, a multidecade endeavor to promulgate a unified definition of medical professionalism and “stay ahead of the wave” of its new professional challenges (

American Board of Internal Medicine 1999). The project arose from a consensus that changes occurring both inside and outside the training environment, such as relaxed evaluation criteria and “stress surges” caused by changes in the health care delivery system, were eroding professional standards. The project had three other related goals: to raise the concept of professionalism into the consciousness of all within internal medicine, to provide a way for program directors to inculcate professionalism concepts via training programs, and to create strategies for evaluating the professionalism of medical trainees.

With the belief that professionalism entails measurable professional qualities, Project Professionalism developed new guidelines for shaping training programs. Furthermore, it advocated certification as a means of ensuring integrity across the profession. The project resulted in four recommendations for curricular requirements of professional certification programs: physician accountability, humanistic qualities, physician impairment, and professional ethics. The project brief also emphasized the importance of vignettes in inculcating professional standards and included a section explicating the “signs and symptoms” of unprofessional conduct to aid trainees in recognizing common patterns of unprofessional conduct in complex everyday scenarios.

The importance of inculcating professionalism among medical trainees is underscored by the inclusion of professionalism as one of six core competencies promulgated by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education in 2002 (Educational Commission for Foreign Medical Graduates 2012). Residents in all training programs must meet a number of professionalism milestones, although these vary according to specialty.

For psychiatry, the latest iteration of professionalism competencies, effective in 2021, comprises three domains: “Professional Behavior and Ethical Principles,” “Accountability/Conscientiousness,” and “Well-Being” (

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education 2020). The inclusion of “Well-Being” attests to the growing recognition of the vital role of provider well-being in promoting professionalism and ethical behavior. This topic is explored further in the section “Professional Well-Being” later in this chapter.

THE CENTRALITY OF ETHICS IN THE CARE OF PEOPLE WITH MENTAL ILLNESS

Ethics is fundamental to the practice and identity of mental health professionals. Mental illness, by definition, affects the most basic, human aspects of ourselves—our emotions, ideas, beliefs, capacity for relationships, and abilities to engage in meaningful activities and perform diverse roles. Opportunities for people living with mental illness are frequently constrained. Living with a mental illness—whether episodic or chronic—is often associated with social isolation, alienation from family and friends, and loss of important functions. People with mental illness across the spectrum of severity and their families must muster courage and even take risks to seek help, often confronting significant barriers to care not encountered in the treatment of physical health conditions (

Conner et al. 2010;

Fox et al. 2018;

Link and Phelan 2006). Moreover, mentally ill individuals have often struggled alone for years and are frequently misdiagnosed before receiving appropriate clinical attention. Mental illness is also often deeply stigmatizing and poorly understood, creating new sources of vulnerability (e.g., prejudicial attitudes, implicit and explicit bias) that may make some individuals more likely to experience poverty, marginalization, exploitation, neglect, and abuse (

Luciano et al. 2014;

Peris et al. 2008;

Roberts and Roberts 1999). Individuals from certain backgrounds, moreover, may experience additional concerns about stigma related to seeking mental health care (

Krill Williston et al. 2019).

Mental health professionals are expected to do what is right as healers and to regard patients as complete persons deserving of dignity and respect. Becoming worthy of the confidence and trust of people who have experienced suffering fundamentally requires that professionals develop and work to maintain a deep capacity for self-reflection and a sensitivity to the ethical nuances of their work (

Roberts 2016). In this way, ethics and professionalism can be viewed as central pillars of clinical excellence (

Chisolm et al. 2012). Psychiatrists, psychologists, and other mental health professionals learn patients’ most sensitive thoughts, hopes, and fears; those with mental illness place great trust in their caregivers.

The mental health field is composed of professionals from a wide variety of disciplines, including, but not limited to, psychiatrists, psychiatric nurses, psychotherapists, counselors, psychiatric social workers, addiction therapists, and psychologists with diverse subspecialties. Each of these disciplines has its own ethical tradition expressed in characteristic codes of ethics that continue to be expanded and refined to meet emerging challenges. In addition, primary care practitioners have increasingly been called on to perform many mental health care functions, including routine screening for depression, anxiety, and substance use disorders (

Siu et al. 2016). Mounting pressures weigh on these providers, as well as health care organizations such as accountable care organizations, to evaluate for, treat, and report on (e.g., through pay-for-performance metrics) these disorders in order to receive incentive payments, despite relatively thin evidence for the effectiveness of these incentives (

Counts et al. 2019).

Given that primary care clinicians may have received relatively little education regarding the diagnosis and treatment of mental illness and are often uncoached regarding the unique ethical and legal dimensions involved in mental health care (e.g.,

Tarasoff v. Regents of the University of California [

1976] rulings, involuntary commitment procedures, transference issues, manifestations of bias, and boundary crossings or transgressions), additional questions will be raised about the adequacy of the standards for such care provided within—and ethical safeguards incorporated into—these non–mental health care settings (

Reynolds and Frank 2016). As integrated behavioral health models are increasingly regarded as important in cost-effective approaches to address shortages of mental health care (

Woltmann et al. 2012), mental health providers may be placed in ethically challenging positions—for instance, by being asked to triage patients quickly, to parse their time differently to help manage larger panels of patients, or to provide treatment recommendations for patients whom they have not met or personally evaluated. Such scenarios involve a scarcity of individual attention and can increase clinicians’ reliance on implicit and explicit individual bias in making predictive and real-time judgments and decisions (

Saposnik et al. 2016). This effect can scale: by the same token, patterns of bias in the medical profession can serve to reinforce discrimination and perpetuate systemic mental health inequities (

Compton and Shim 2015;

Dehon et al. 2017). It is increasingly understood that many forms of bias are rooted in cognition and unconscious beliefs, and that medical professionals are just as susceptible to biased thinking as the general population (

FitzGerald and Hurst 2017). Therefore, a commitment to rooting out bias is increasingly viewed as a professional value and necessary to uphold certain bioethical principles, such as nonmaleficence and justice. How to mitigate bias in mental health care, through clinician training and other means, is thus a question of immediate concern for ethics and professionalism.

In the field of mental health, clinicians must work with issues of personhood and autonomy while continuously grappling with definitions of health and illness. Ethical issues of beneficence, nonmaleficence, confidentiality, altruism, justice and nondiscrimination, professionalism, trust, and related abstract concepts are very real factors in daily work. Ethical considerations may take the form of clinical care dilemmas or conflicts—for example, in deciding whether a person should be admitted to the hospital involuntarily, in assessing whether a poststroke patient is capable of the decision to decline recommended treatment, and in determining whom to inform when a patient expresses homicidal intent. Ethically rich aspects of care also serve as the basis for some of the most gratifying work—for instance, when a clinician reaches a solution to a complex series of dilemmas.

The value of ethics to the mental health professions stems also from the unique place of mental health within the larger fields of health care and social service. Mental health professionals, as well-trained observers of behavior, have developed a broad yet nuanced understanding of human nature and are often well suited to managing complex situations that require synthesizing ethical, medical, psychological, legal, and psychosocial perspectives. Mental health clinicians are thus often called on to help clarify and resolve ethical dilemmas that arise in the care of medical patients, to join ethics committees, and to reflect publicly on ethical questions arising in society (

Bourgeois et al. 2006). Mental health professionals are also frequently involved in the conduct of clinical research involving volunteers with mental illnesses. Numerous ethical challenges can arise in these studies and all deserve special attention (

Dunn and Roberts 2021).

In short, the importance of ethics is rooted in the powerful and intimate role that clinicians play in the lives of their patients who experience mental illnesses. Mental illnesses cause great suffering, are complex and often misunderstood, and may give rise to significant vulnerabilities in present-day society. Ethics is critical to mental health providers because of the diverse roles, commitments, and responsibilities they assume in their professional lives.

NEUROETHICS AND NEUROSCIENCE

Over the past few decades, neuroscience has taken up a central role in medicine as the conceptual basis for understanding and treating mental illness. Mental illness, as an illness of the brain, is perceived as having a biological basis. Yet, unlike other organs, the brain gives rise to the mind, is generative of identity, and sustains the mental activity by which people develop the morals, ethics, attitudes, beliefs, and scientific facts that shape society. The study of the brain’s functioning and the recursive application of advancements in our metacognitive understanding to influence the brain and mind therefore carry ethical questions that are not present elsewhere in the biological sciences. These questions belong to the emerging field of neuroethics.

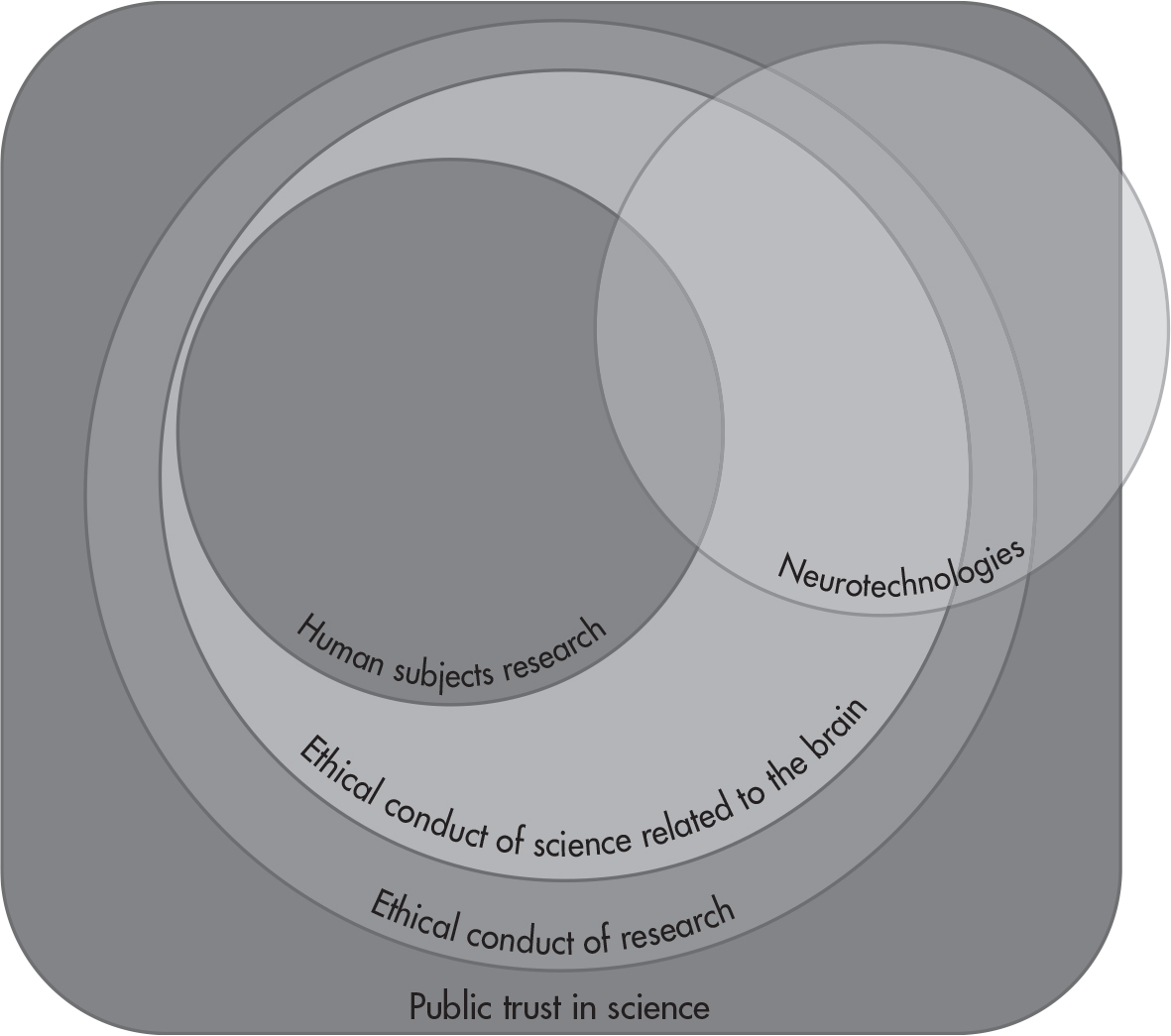

Neuroethics is a capacious and interdisciplinary field implicated both in traditional ethical domains, such as human subjects research and the active question of public trust in science, as well as emerging domains, including neurotechnologies, neurolaw, and philosophy of cognition (see

Figure 1–1).

The advancement of the empirical basis of neuroscience depends on the ethical participation of diverse individuals in research, including individuals with mental illness. Neuroscience research upholds the principle of beneficence by seeking to reduce the immense global disease burden represented by mental illness. Secondary interests of neuroscience research are related to concepts such as the intrinsic value of knowledge about the self and the entrusted role of basic science in making discoveries that can enable broader epistemic value for humanity. As treated by

Illes (2017) in greater depth, topics in neuroethics include emerging biomedical technologies, emerging neuroimaging technologies, wearables and mobile health technology, neuromodulation, neurotechnology research, the role of technology in the lives of young people, brain death and the definition of death, ethical issues in neurodegenerative conditions, environmental neuroethics, the neurobiology of addiction, and neuroscience in the law, among other topics, which go beyond the scope of this book.

ETHICS EDUCATION: IMPARTING ETHICS KNOWLEDGE AND PROFESSIONAL VALUES

Ethics education, including ethics education in psychiatry and the related mental health professions, has evolved over the last four decades. Initially, ethics instruction was felt to be inappropriate, as it was believed that one’s morals were learned early in life and were not necessarily teachable (

Pellegrino et al. 1985). Ethics curricula have advanced from formal didactic and cognitive models of instruction to a growing recognition of the need for a developmental approach that also encompasses affective aspects of decision-making (

Christakis and Feudtner 1993). Early on, ethics education emphasized rule-based codes of conduct and then the clinician-patient relationship. More recently, increasing attention is given to public health and to community obligations and responsibilities, such as those expressed in the widely adopted Professionalism Charter (

American Board of Internal Medicine Foundation et al. 2002). Similarly, the need to attend to all voices—including individuals with lived experience of mental illness, consumers of mental health care services, and underrepresented populations—as full partners in clinical care represents a departure from prior, more hierarchical and paternalistic models (

Institute of Medicine 2001). This shift has led mental health professionals and their teachers to encounter new ethical dilemmas, such as expanded authority and scope of practice for non-doctoral-level practitioners and the empowerment of patients in clinical decision-making expressed through novel tools like psychiatric advance directives (

Murray and Wortzel 2019). To successfully negotiate this new moral territory, mental health professionals will require a different skill set from their predecessors, such as the ability to mediate disputes, negotiate power sharing, manage ever more complex legal situations, and participate in struggles for social justice and political parity, without which adequate mental health care and its funding cannot be achieved.

Cultivating an understanding of ethics is vital to providing competent and compassionate mental health care and to fulfilling mental health professionals’ diverse, socially vital, yet complicated roles and obligations. Furthermore, ethical behavior is a core feature of what it means to be a health care professional. Interest in teaching, modeling, and assessing professionalism in health care includes a commitment to ensuring that professionals understand and can reason through complicated ethical issues and hold themselves to the highest ethical standards. The reinvigorated interest in ethics and professionalism derives, in part, from the perception that over the last several decades, health care providers have lost some of the moral stature historically afforded them. Another reason for the emphasis on professionalism and ethics in health care education is the rapidly changing health care environment, with numerous emerging and complex health care advances in terms of methods of care, modes of delivery, and systems of care. Concurrently, the demographic and sociocultural contexts of health care delivery demand that future clinicians be trained to attend to cultural and other dimensions of care that, although previously underappreciated and untaught, now sit squarely in the domain of professionalism.

Every professional must learn and abide by the regulations and laws governing his or her behavior; this is a fundamental commitment of a profession and a basic part of professional education. For example, regulations surrounding research involving human volunteers or participation by living human “subjects” in studies must be overseen by an appropriate institutional review board and oftentimes, in addition, by a data and safety monitoring board. These oversight bodies must be engaged prior to the initiation of research by the professional who proposes to perform the research work. The law requires that physicians and other clinicians, under nearly all circumstances, obtain a patient’s informed consent prior to initiating a procedure or treatment or research participation. It is important to emphasize, however, that legal behavior is not the same as ethical behavior. The law sets parameters around choices, delimiting the acceptable options under a given set of circumstances (

Roberts and Dyer 2004). In most cases, however, the law does not tell providers what to do. In other words, the law rules out certain options, providing negative imperatives; in contrast, ethical analysis helps us to construct positive imperatives, thereby “ruling in” one or more ethically defensible options. In the case of informed consent, for example, the law does not tell providers what to do when a patient refuses a recommended treatment or will not adhere to treatment recommendations. Providers must have a solid grasp of ethical aspects of care to resolve such dilemmas. These dilemmas are often evolving, dynamic situations, not easily encapsulated as a specific set of circumstances to which a single law could apply.

Professionalism expectations or standards, when interpreted as a restricted set of normative beliefs and behaviors, have come under criticism for contributing to a narrow and inflexible view of what is “acceptable” in medicine and the health professions. Professionalism has also been “weaponized” in certain situations, as noted in the literature (

Frye et al. 2020;

Roberts 2020), when it is used to create an unwelcome environment for individuals who identify as nonmajority. Implicit expectations of professionals defined by societal biases (e.g., around whiteness, around heteronormative identity, around hair, weight, age) also contribute to skepticism toward old-fashioned views of professionalism (

Frye et al. 2020). We suggest that professionalism is intrinsically grounded in the ideals of a profession (e.g., truthfulness, respect for dignity of patients, humility), although the understanding of how such ideals are expressed at any given moment in history, society, and culture will change. A working understanding of the ideals of the profession and how they translate into professional practices and actions is crucial in informing ethical decision-making.

Ethics education, therefore, is strongly linked on conceptual grounds to the development and preservation of professionalism in trainees. For mental health providers, the special privileges and obligations accompanying their roles make ethics education a crucial component of training and lifelong learning.

Modern curricula have placed greater emphasis on both formal didactic and experiential methods—including structured ethics instruction, group discussions of real cases, and written reflections—directed at the goal of having learners acquire essential ethics-related skills as outlined above. The educational approaches used have been varied, and few data are available enabling comparison of different educational strategies. Early work conducted among medical students indicates that case-based and discussion-oriented approaches (

Roberts et al. 2004b,

2005,

2007) and participant-oriented, empathy-focused approaches (

Roberts et al. 2007) may be effective methods for teaching about clinical and research ethics, although much more empirical work is needed.

In addition, increasing recognition is being paid to developing ethics skills among students who are actually working with patients clinically (i.e., as opposed to those attending lectures, such as medical students in their preclinical years). Thus, ethics educators may ask students to describe cases they have encountered, given that applying ethical analytic skills to real-life situations may have more resonance for learners. Several studies have examined the content of students’ reflections on ethical dilemmas they have encountered. For instance,

Kelly and Nisker (2009) reported that students frequently felt that an ethical issue had arisen, but they nevertheless hesitated to bring it to their supervisors’ attention, out of concern about how their performance would be evaluated. Moreover, the most commonly described dilemmas noted by students involved informed consent or inadequate care. Such findings suggest that despite trainees’ attunement to ethical issues, the nature of the supervisor-trainee relationship may negatively affect students’ willingness to raise these important issues.

In a survey of over 200 psychiatry residents’ perspectives on ethics education, respondents affirmed the importance of ethics education, but also expressed a need for more training in core ethical concepts and issues (

Jain et al. 2011a,

2011b;

Lapid et al. 2009). Residents also desired educational approaches grounded in clinical practice, role modeling, and teaching by experts. Topics related to conflict of interest are also of great concern to psychiatry residents. Given that the pharmaceutical industry spends $20 billion marketing to health care professionals (

Schwartz and Woloshin 2019), residents must be aware of the ethical considerations of receiving gifts from the pharmaceutical industry and how to ethically handle relationships with the pharmaceutical industry in general (

Jain 2007,

2010).

Another priority for ethics-related education for mental health professionals is the goal of training clinicians who will be culturally attuned to their patients. Just as learning to identify ethical dimensions and issues in their work comprises a fundamental skill set for developing mental health professionals, gaining a working knowledge of and facility with key cultural aspects of care is also vital to upholding professional obligations. As articulated in the

Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (2018) competency of professionalism, residents must “demonstrate a commitment to professionalism and an adherence to ethical principles” (see

Table 1–5). The National Association of Social Workers’ Code of Ethics places great emphasis on cultural sensitivity, situating it solidly within the framework of social workers’ set of core values as part of striving for social justice:

Social workers pursue social change, particularly with and on behalf of vulnerable and oppressed individuals and groups of people. Social workers’ social change efforts are focused primarily on issues of poverty, unemployment, discrimination, and other forms of social injustice. These activities seek to promote sensitivity to and knowledge about oppression and cultural and ethnic diversity. Social workers strive to ensure access to needed information, services, and resources; equality of opportunity; and meaningful participation in decision-making for all people. (

National Association of Social Workers 2017)

PROFESSIONAL WELL-BEING: ITS FUNDAMENTAL ROLE IN ETHICS AND PROFESSIONALISM

Although, in years past, the concept of professional well-being has not frequently been encountered in the theoretical and empirical ethics literature, it is now widely acknowledged that providers’ well-being is crucial to their ability to enact the virtues, knowledge, and skills that comprise ethics and professionalism. Threats to provider well-being are also threats to ethics and professionalism. As a corollary, opportunities to enhance well-being provide avenues to improving providers’ capacities to practice ethically and with professionalism.

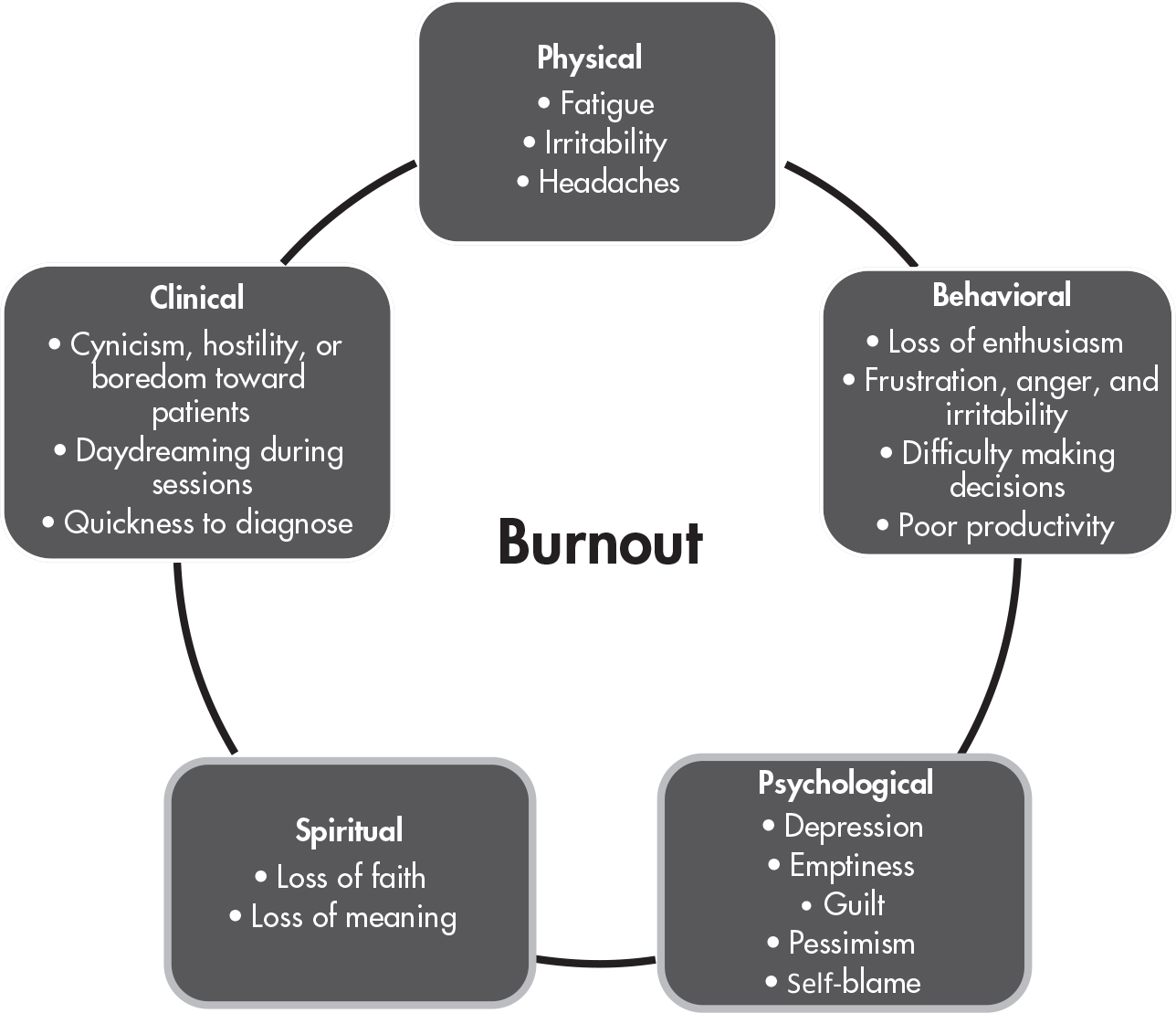

Dramatic changes over the last 30–40 years in the health care system and the practice of medicine—changes that seem to have accelerated in the last 10 years—have profoundly affected the landscape in which providers now find themselves. These changes—including significantly greater rates of clinician employment by large health care systems (vs. private practice), the proliferation of electronic health records, decreases in clinician autonomy, an emphasis on productivity, the weakening of traditional confidentiality protections, and the replacement of many licensed positions with less trained staff—are often cited as primary causes of provider “burnout” (see

Figure 1–2).

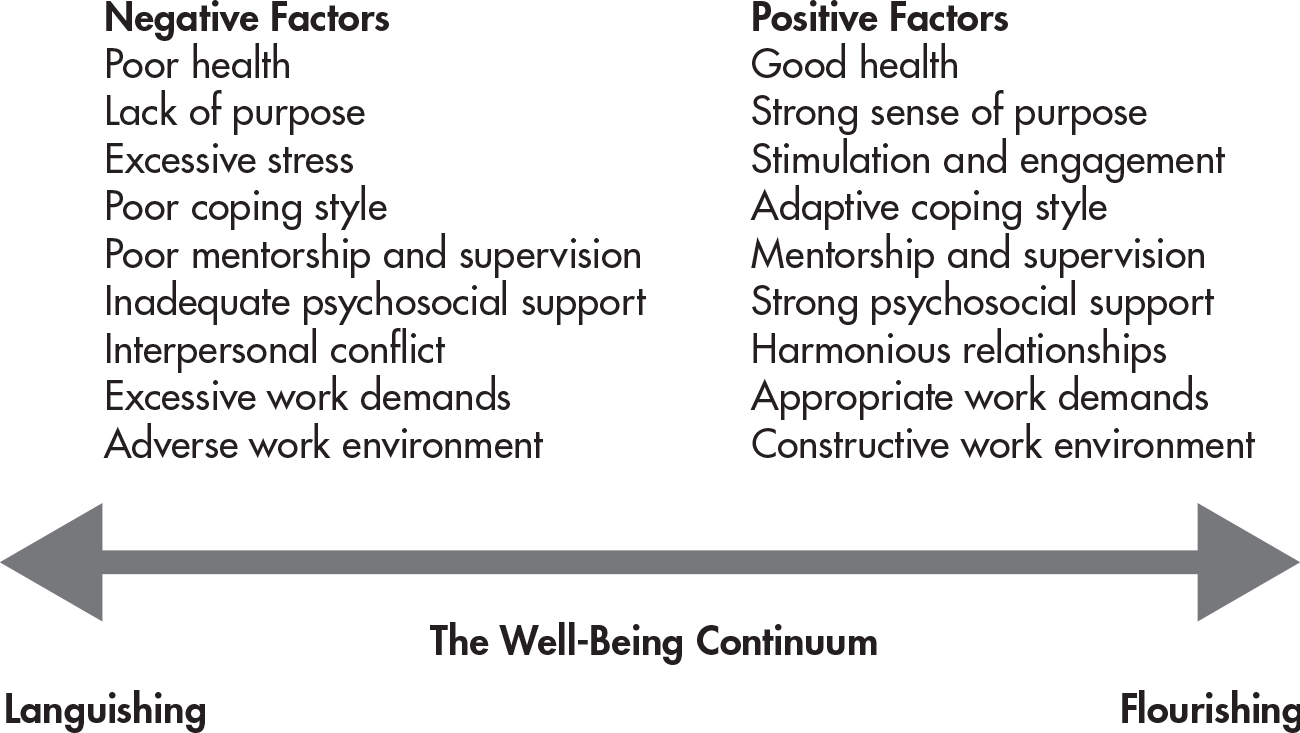

Burnout, however, is not an all-or-none category (i.e., in terms of whether a provider is or is not “burned out”). Rather, it is more productive to think of burnout as residing along a continuum—from well-being and personal and professional fulfillment on one end of the spectrum, to personal and professional impairment, significant distress, and to mental illness on the other end of the spectrum (see

Figure 1–3). We all have both risk and protective factors for the development of burnout. Mental health professionals may be at elevated risk, by virtue of the “secondary traumatization” that can occur by working with individuals who have experienced severe histories of mental illness, abuse, or trauma (

Maslach and Leiter 2016). Additional risk factors for burnout among mental health providers are listed in

Table 1–6.

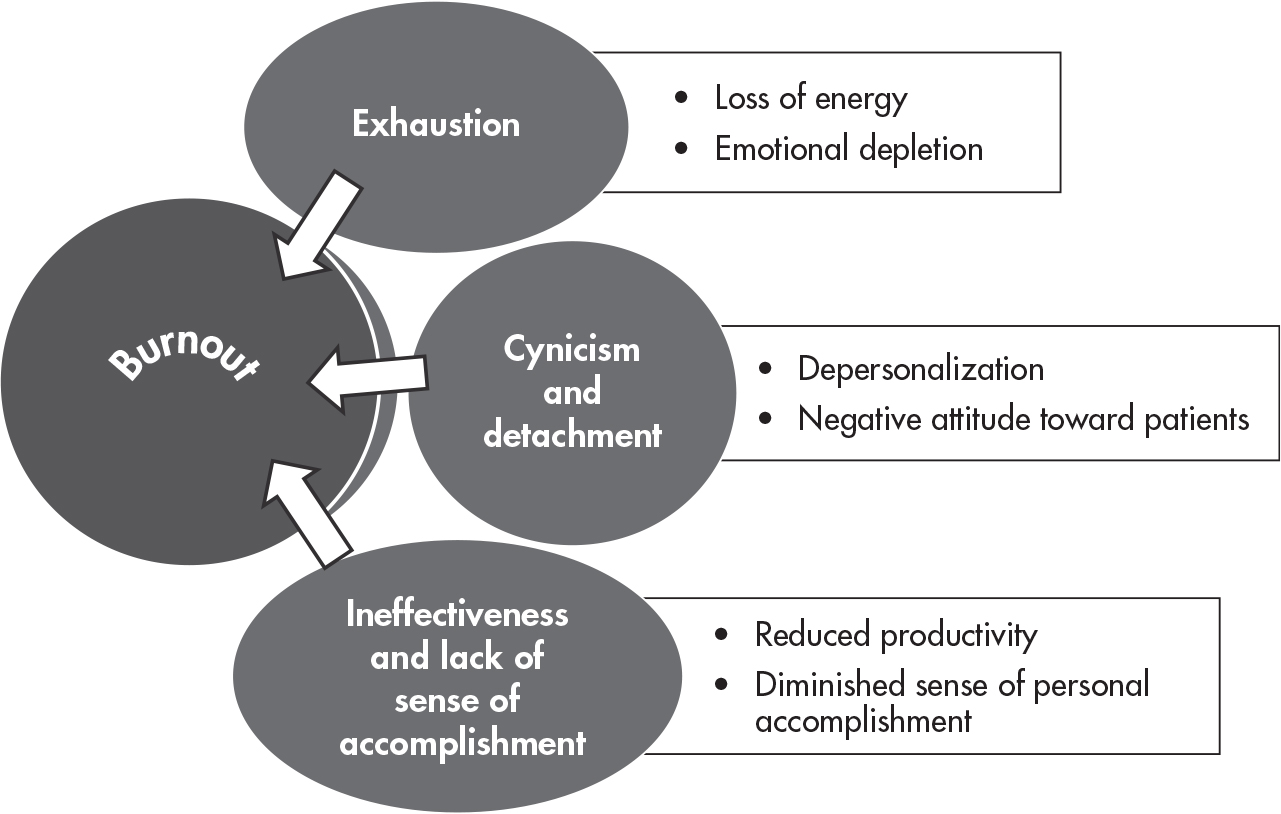

Definitions of “burnout,” it should be noted, continue to evolve. Although initially described as having three cardinal features—emotional exhaustion, depersonalization, and a decreased sense of personal accomplishment (

Maslach and Jackson 1981)—these features have been more recently elaborated on as “dimensions” (see

Figure 1–4):

The exhaustion dimension was also described as wearing out, loss of energy, depletion, debilitation, and fatigue. The cynicism dimension was originally called depersonalization (given the nature of human services occupations), but was also described as negative or inappropriate attitudes towards clients, irritability, loss of idealism, and withdrawal. The inefficacy dimension was originally called reduced personal accomplishment, and was also described as reduced productivity or capability, low morale, and an inability to cope. (

Maslach and Leiter 2016, p. 103)

In the field of mental health care, an additional and perhaps less discussed source of distress is the enormous moral pressure of feeling constantly that one or one’s team is being “asked to do more with less.” For example, a social worker on an inpatient psychiatric unit may be asked by a resident to find apartment housing for an individual with serious mental illness whom the social worker knows cannot survive without intensive case management, which is unavailable; or a psychologist may be told he can only provide six sessions of psychotherapy for a profoundly depressed adolescent and must submit detailed session notes if he wishes to receive payment from an insurance company.

Yet another pressure affecting professional development is the pressure to conform. Professionalism is both a set of discernible qualities and an embodied social construct that relies, in part, on images and narratives selected according to specific norms and preferences. Many images of the physician overlap in the history of medicine; the overwhelming majority of these images are white and male. Physicians continue to hold an implicit white preference (

Sabin et al. 2009). Members of the profession must guard against normalizing privileged, racist, and arbitrarily constrained forms of professional identity and behavior. Conforming pressures can cause inequity and distress for individuals who do not see any room for themselves in their field—many of these individuals may already face compounded inequities due to race, gender identity, religion, cultural background, or other factors. For individuals whose identities remain underrepresented in medicine, professional self-discernment may be stifled by perceived “necessary behavior” (

Babaria et al. 2009). Microaggressions, othering, and belittlement are examples of derivative forms of harm based in implicit and explicit bias that increase risk for burnout and prevent equity in our professional fields.

Fostering one’s own well-being, as well as the well-being of one’s colleagues and trainees, will remain critical to maintaining and promoting professionalism and ethics within the field of mental health care. Professionals with a greater sense of well-being will not only experience greater personal and professional fulfillment but will also be better able to practice the essential ethical skills of mental health professionals.