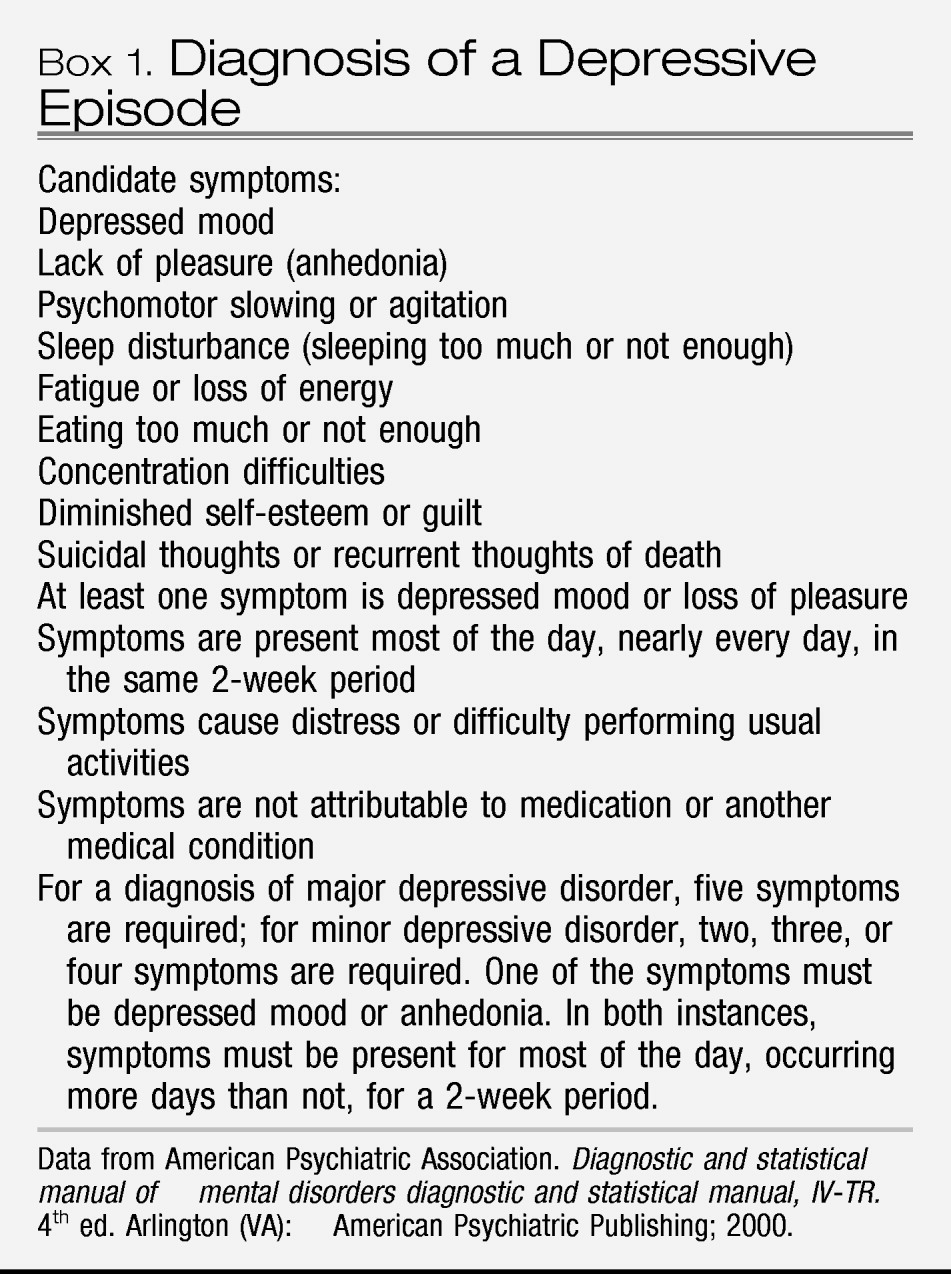

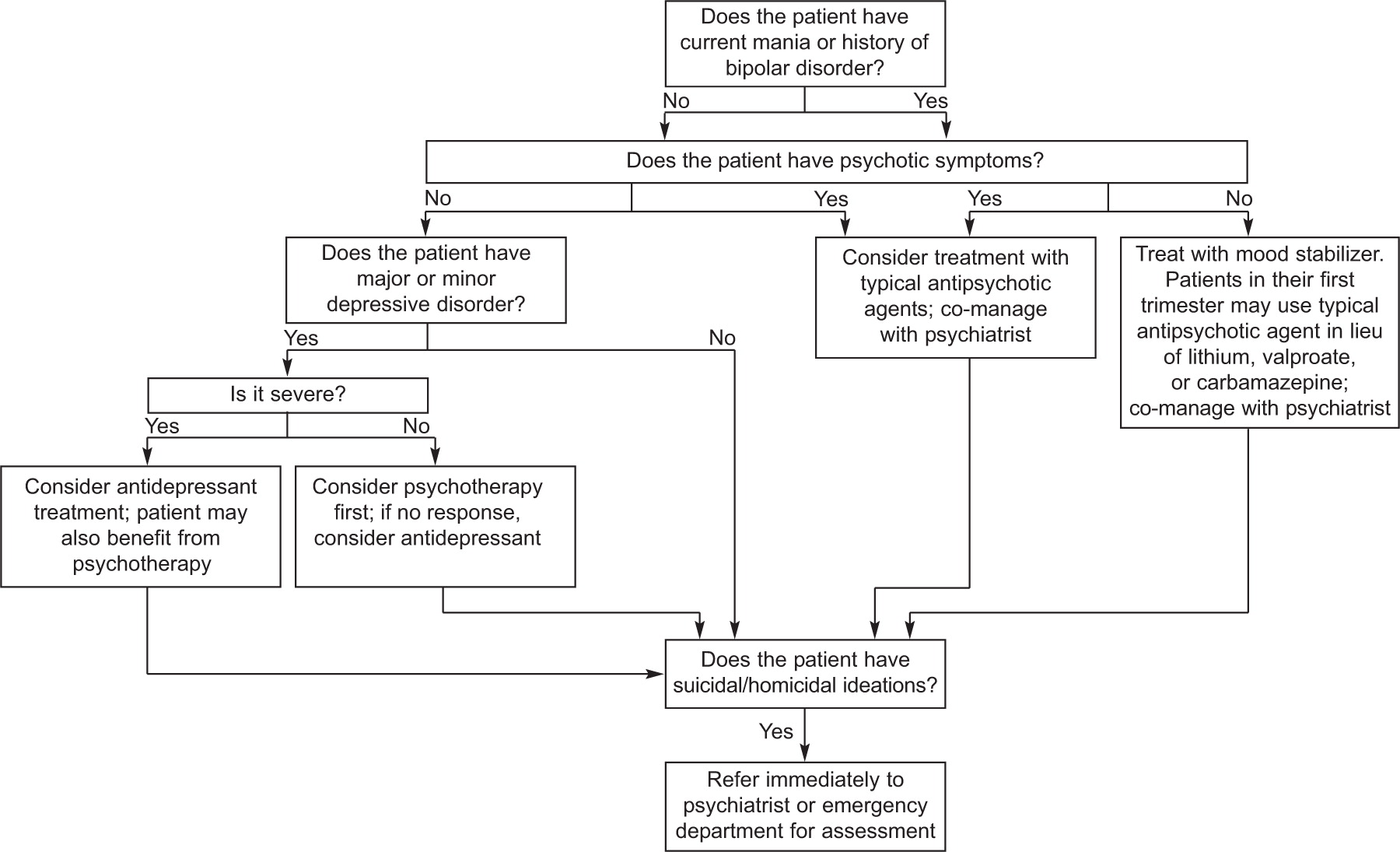

Although the general public commonly refers to “depression,” the term connotes a range of disorders that are collectively termed “mood disorders.” Classification of mood disorder subtype depends on the course of the mood disturbance, comorbidity with manic symptoms, and severity. Each subtype has treatment implications, and thus it is helpful for clinicians to be familiar with the differences between conditions. According to the

American Psychiatric Association Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition (

4), an episode of major depressive disorder (

Box 1) can occur in a woman with no history of a mood disorder (unipolar major depressive disorder, single episode) or one who has had many episodes in her life, ie, “recurrent unipolar major depressive disorder.” A major depressive episode can be classified as mild, moderate, or severe, depending on the number and severity of symptoms. In nonpregnant women, antidepressant treatment is a recommended first-line treatment for major depression of any severity and psychotherapy is recommended as first-line therapy for mild to moderate depressive episodes (

5). The greater the number of previous episodes of major depressive disorder, the higher the likelihood that another episode will occur. In general, approximately one-half of women who have one episode of major depressive disorder will have another event, whereas a history of two episodes increases the risk to approximately 80% (

6). The treatment implications are that once a woman has had at least three episodes of major depressive disorder in her life, her risk of a recurrence is sufficiently high that clinicians should consider maintenance, lifetime, antidepressant therapy (

5). Of the various types of mood disorders, “unipolar” major depressive disorder, that is depression without lifetime mania or hypomania, is the most common. Other types of unipolar mood disorders can be chronic or acute and include dysthymic disorder and minor depressive disorder. Dysthymic disorder is a mood disturbance that endures for 2 years or more and, although it is characterized by fewer and less severe symptoms of depression, the chronicity of the condition confers morbidity. Minor depressive disorder is acute and the candidate symptoms are the same as those found for major depressive disorder (

Box 1), but only two to four symptoms are required for the majority of 2 weeks, rather than the five symptoms required for major depressive disorder. Both of these disorders are associated with either clinically significant distress or functional impairment.

Women with unipolar major depressive disorder who present either in pregnancy or after delivery commonly have difficulties with sleep, energy, and appetite. To differentiate these symptoms from typical experiences of pregnancy or being postpartum, obstetricians are advised to rely on assessment of cognitive symptoms that occur in depressed individuals. Mothers with depression are often anxious and worried about the health of their infants, but they may be despondent and strikingly uninterested in either their pregnancy or the activities of their infants. It is typical for women to express guilt and feelings of worthlessness that can spill over into concerns about their capacity to be an adequate mother. Whereas reassurance can be helpful to women who have mild depressive symptoms, a patient with major depressive disorder typically does not respond to support and encouragement and will require a therapeutic regimen such as medication, psychotherapy, or both of these.

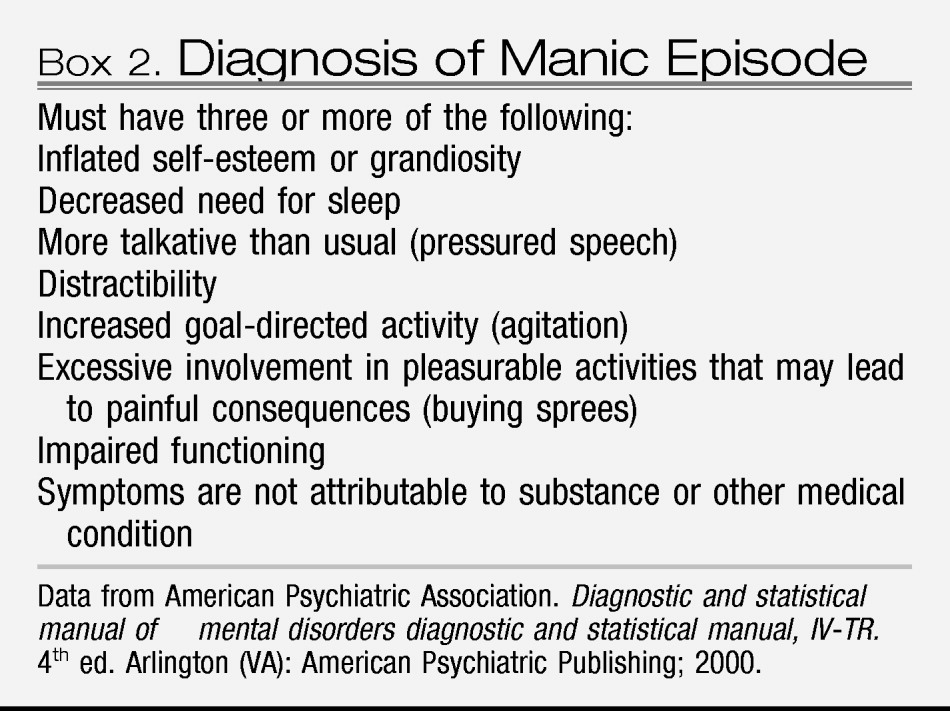

If a woman with major depressive disorder also has a history of mania or has experienced manic symptoms with depression (

Box 2), then her illness is bipolar disorder rather than unipolar major depressive disorder. Manic symptoms may have occurred in temporal proximity to major depressive disorder or may have occurred years earlier. A first-degree family member with a history of mania should alert clinicians to the possibility of bipolarity in the patient with major depressive disorder. The familiality of bipolar disorder is strong in that the rate of a bipolar spectrum disorder is increased 14-fold for offspring who have a parent with bipolar disorder. In actual percentages, approximately 5% of children will have bipolar disorder develop and 10% will have a related spectrum disorder if a parent has bipolar disorder (

7). Mood stabilizers (ie, lithium, various anticonvulsant medications, and atypical antipsychotic medications) are the optimal therapeutic choice for individuals with bipolar disorder because antidepressant treatment alone can trigger or worsen manic symptoms. There is increased likelihood of underlying bipolar disorder among women who have a severe and sudden onset of major depressive disorder soon after delivery (

8).

Postpartum psychosis is a term that is used to describe postpartum women with a variety of psychiatric illnesses that do not map onto a single

Diagnostic and Statistical Manual, fourth edition, diagnosis. Women who become psychotic during or immediately after pregnancy may experience any of the following: a single psychotic episode, schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, unipolar major depressive disorder, or bipolar disorder. Studies that have conducted long-term follow-up find that mood disorders predominate in women who become psychotic near the time of delivery (

9–

12); among women with mood disorders and psychosis after delivery, the majority express a clinical course consistent with bipolar disorder over the ensuing years (

9–

12). Given the preponderance of mood disorders among those with postpartum psychosis, we do not specifically discuss postpartum psychosis but instead unipolar and bipolar disorder with psychosis.