The American Board of Medical Specialties (ABMS) and the American Board of Psychiatry and Neurology (ABPN) are implementing multifaceted

Maintenance of Certification requirements to enhance the quality of patient care and assess the competence of physicians over time (

1). Beginning in 2013, for those applying for 2014 MOC examinations, a practice assessment component of maintenance of certification will require physicians to compare their care for five or more patients with “. . . published best practices, practice guidelines or peer-based standards of care and develop a plan to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of his/her clinical activities.” (

1)

Patients with schizophrenia commonly present to specialty mental health settings and comprise approximately 10% of all patients treated by practicing psychiatrists in the United States (

2). Although the lifetime prevalence of schizophrenia is estimated to be 1.0% (

3), schizophrenia is associated with a very high global burden of disease and disability (

4,

5). Early mortality is more common among individuals with schizophrenia, with a lifetime rate of suicide of nearly 5% (

6) as well as early death due to general medical conditions (

7–

10). Disparities in the receipt of general medical care act in concert with an increased likelihood of risk factors such as metabolic syndrome and smoking to accelerate mortality in those with schizophrenia (

9,

10). Individuals with schizophrenia are more likely to be unmarried, jobless, homeless, and incarcerated (

2,

11–

14). They are also more likely to be the targets of violence (

15) but may also become aggressive to others, particularly in association with substance use problems, psychosis or depressive symptoms, comorbid antisocial personality or childhood conduct problems, neurological impairment, history of violence or victimization (

9,

16–

20). Consequently, optimizing the care of individuals with schizophrenia is essential to reducing the considerable economic and human costs of this disorder.

Despite an extensive and robust research base on the treatment of individuals with schizophrenia, national data indicate that many individuals with the illness currently do not receive evidence-based treatments. Physician adherence to the evidence base for pharmacologic treatments is generally high, with over 90% of persons with schizophrenia in treatment receiving antipsychotic medications (

2), but patients may have difficulty accessing medications, contributing to the risk of relapse and suicidal behaviors (

21). Even among those receiving pharmacologic treatments, appropriate and timely monitoring for side-effects and treatment effects are less than optimal (

22). A much lower proportion of persons with schizophrenia receive other recommended pharmacologic treatments or evidence-based psychosocial treatments. For example, national data indicate that fewer than half (39.7%) of all individuals with schizophrenia who were treated by psychiatrists received any evidence-based psychosocial treatment, including illness education, social skills training, vocational rehabilitation, case management, cognitive behavioral or other psychotherapeutic interventions recommended by the American Psychiatric Association (APA) and the Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) practice guidelines (

2). These findings are particularly troubling, as psychosocial and psychopharmacologic interventions have been shown to help provide individuals with schizophrenia significant relief and improved opportunities to lead more fulfilling lives (

23).

Another potential gap in the care of individuals with schizophrenia relates to the identification of co-occurring psychiatric symptoms and/or disorders. Clinical heterogeneity and psychiatric comorbidities are common (

24–

26). High rates of co-occurring mood, anxiety, substance use and personality disorders have been found among patients suffering from schizophrenia (

26–

28). About half of patients with schizophrenia may have co-occurring depression; point prevalence for depressive symptoms is 50% and one-month prevalence is 30%–35% (

27,

28). Estimates for life-time prevalence of co-occurring anxiety disorder range from 15 to 29% (

27). Symptoms of depression and anxiety are considered integral to schizophrenia (

27), and have impact on the course and outcomes of the illness (

27,

29). Moreover, nearly one-half of patients with schizophrenia have a co-occurring substance use disorder (

27), not including nicotine abuse/dependence, which in and of itself has a prevalence that exceeds 50% among patients with schizophrenia (

25,

27,

28,

30–

32). In general, co-occurring psychiatric disorders and symptoms can worsen the course of illness, and are associated with poorer outcomes (

10,

27,

33–

36); thus thorough assessment, identification and management of co-occurring conditions is a significant aspect of care for schizophrenia.

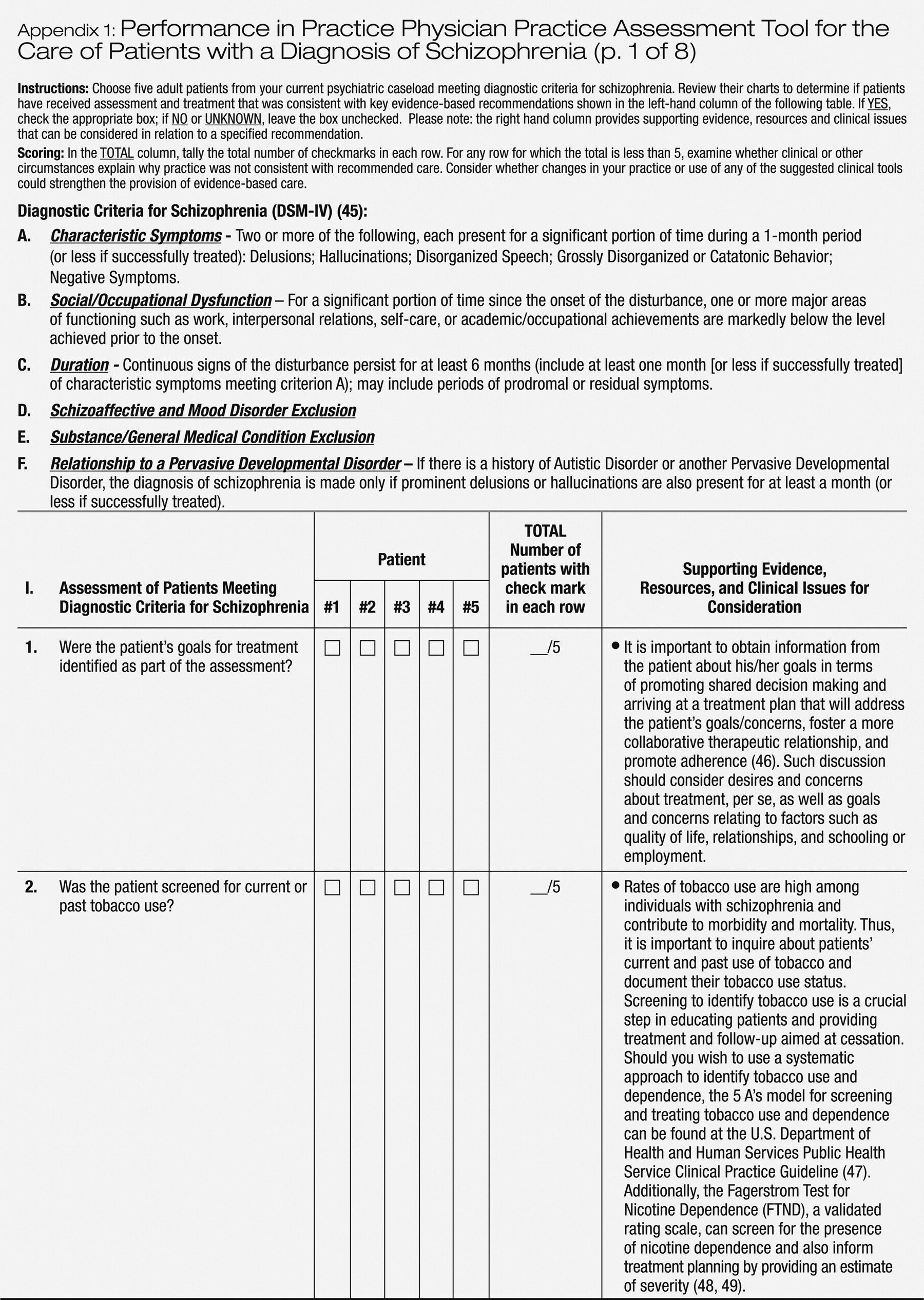

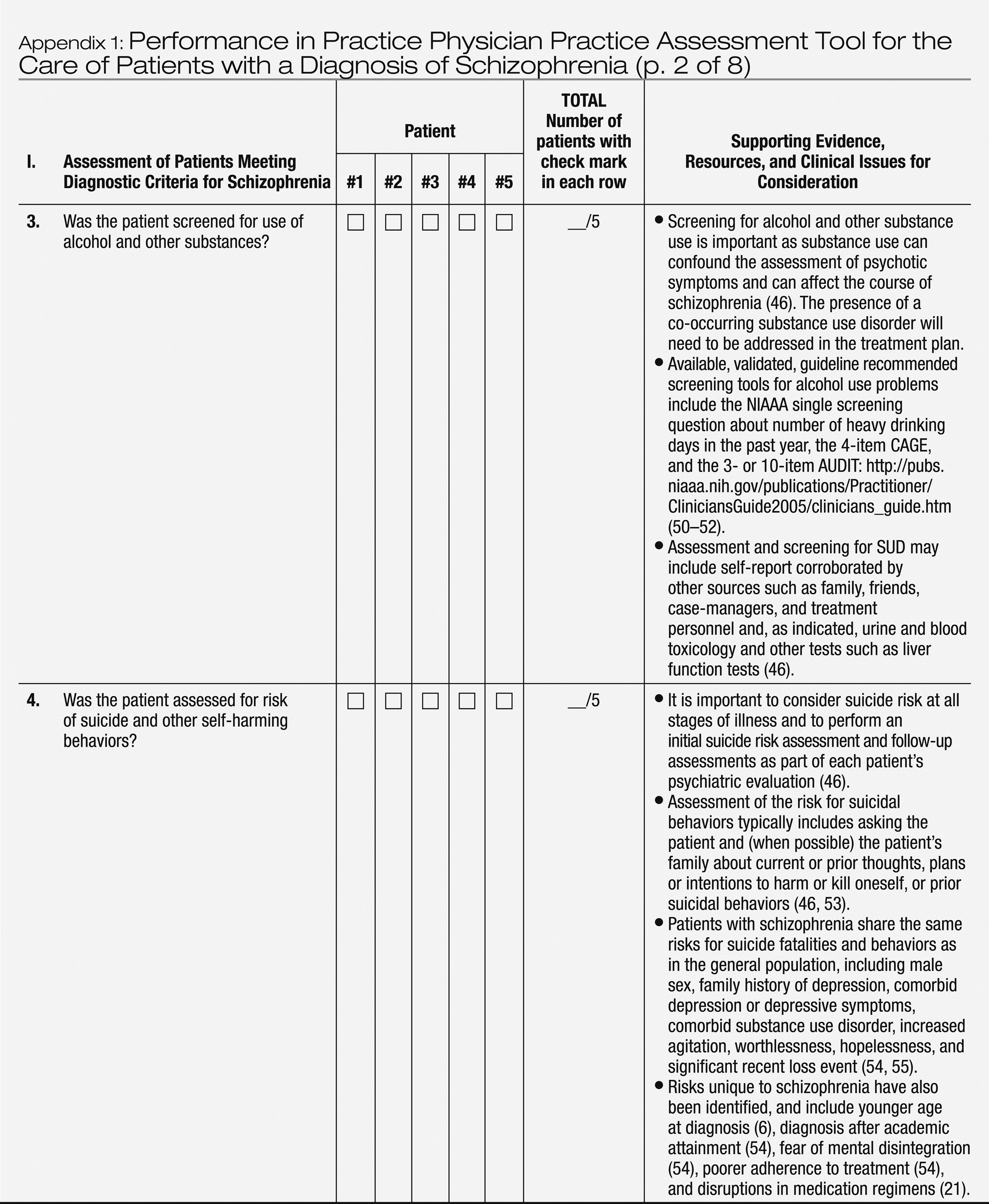

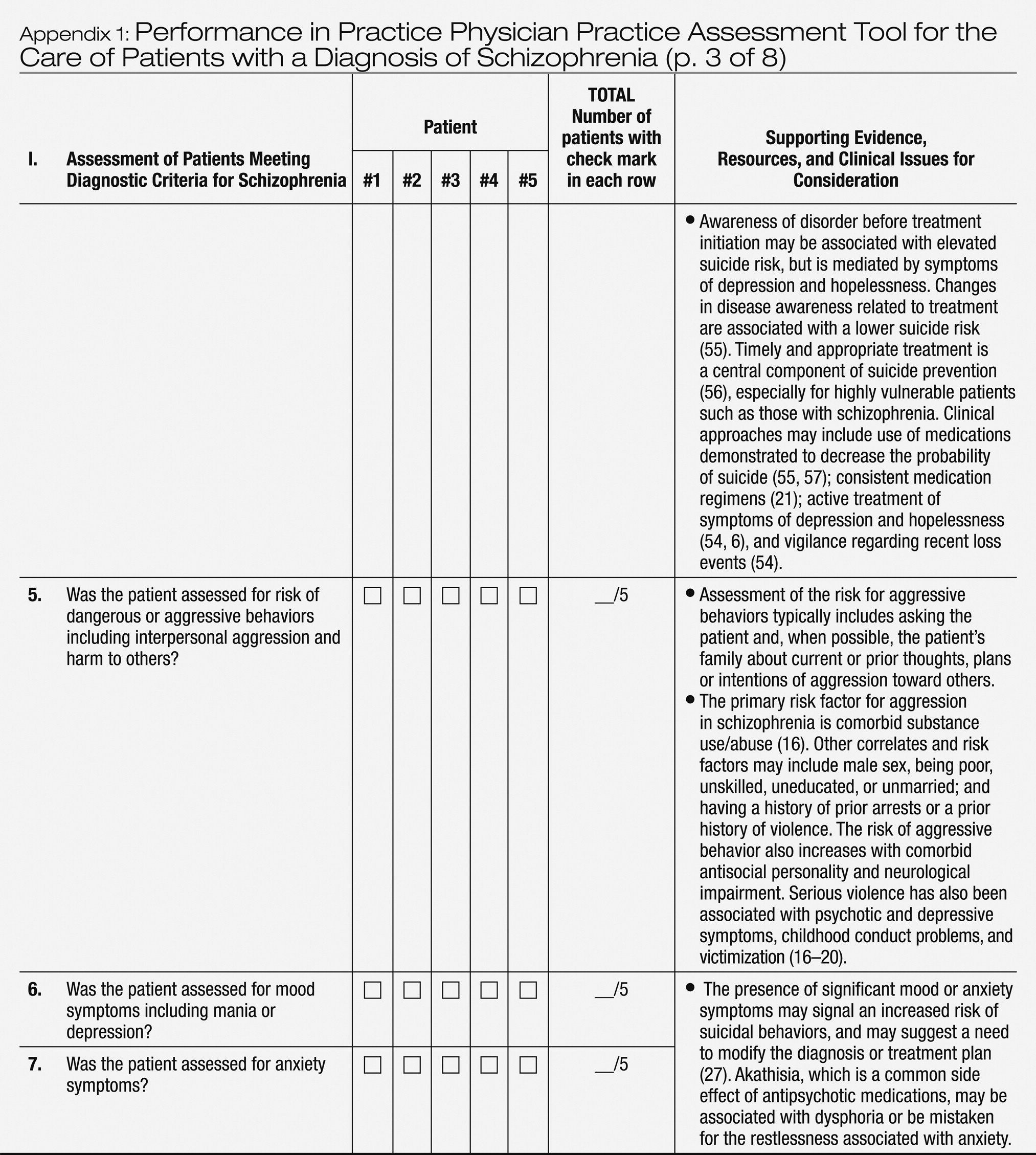

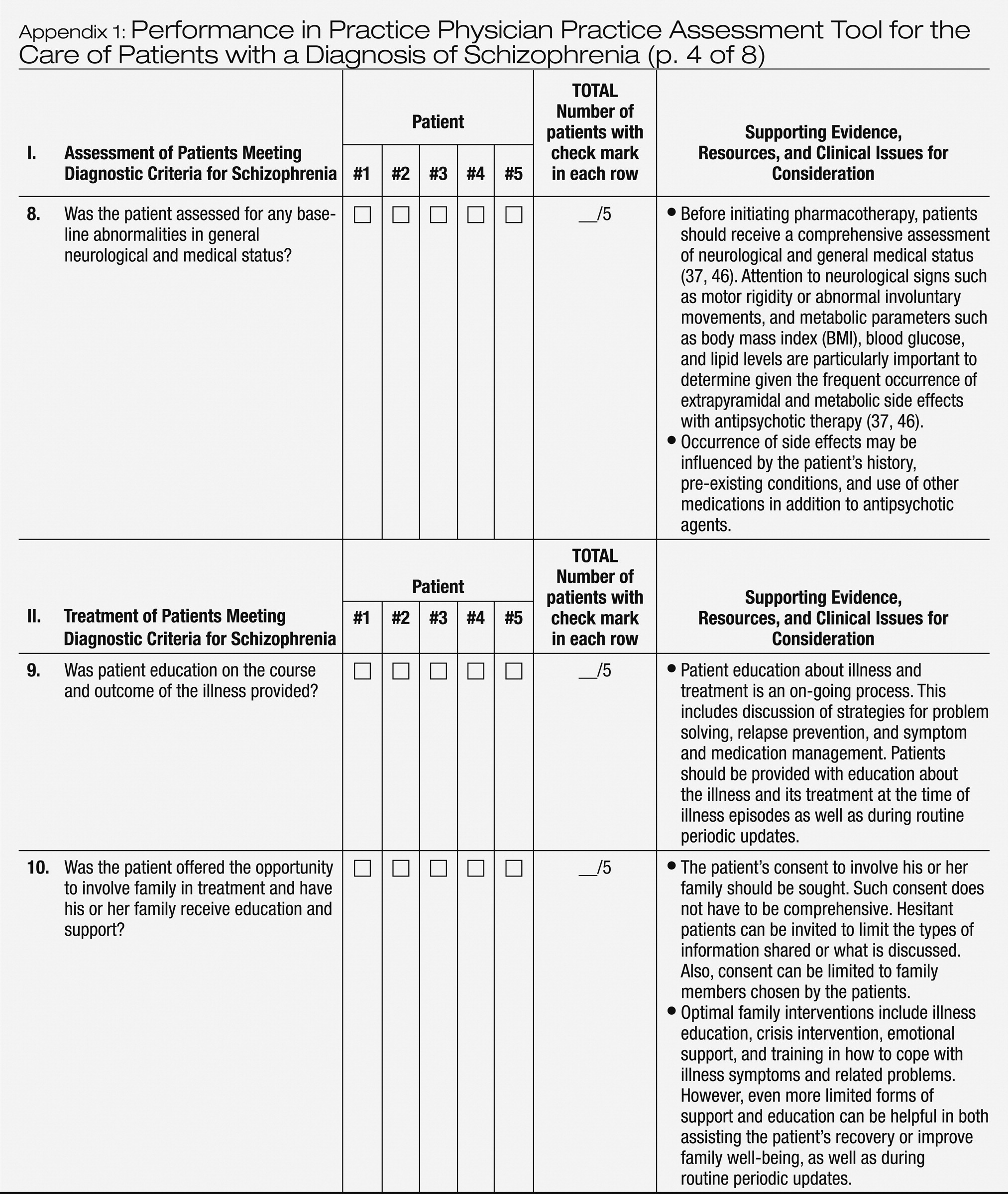

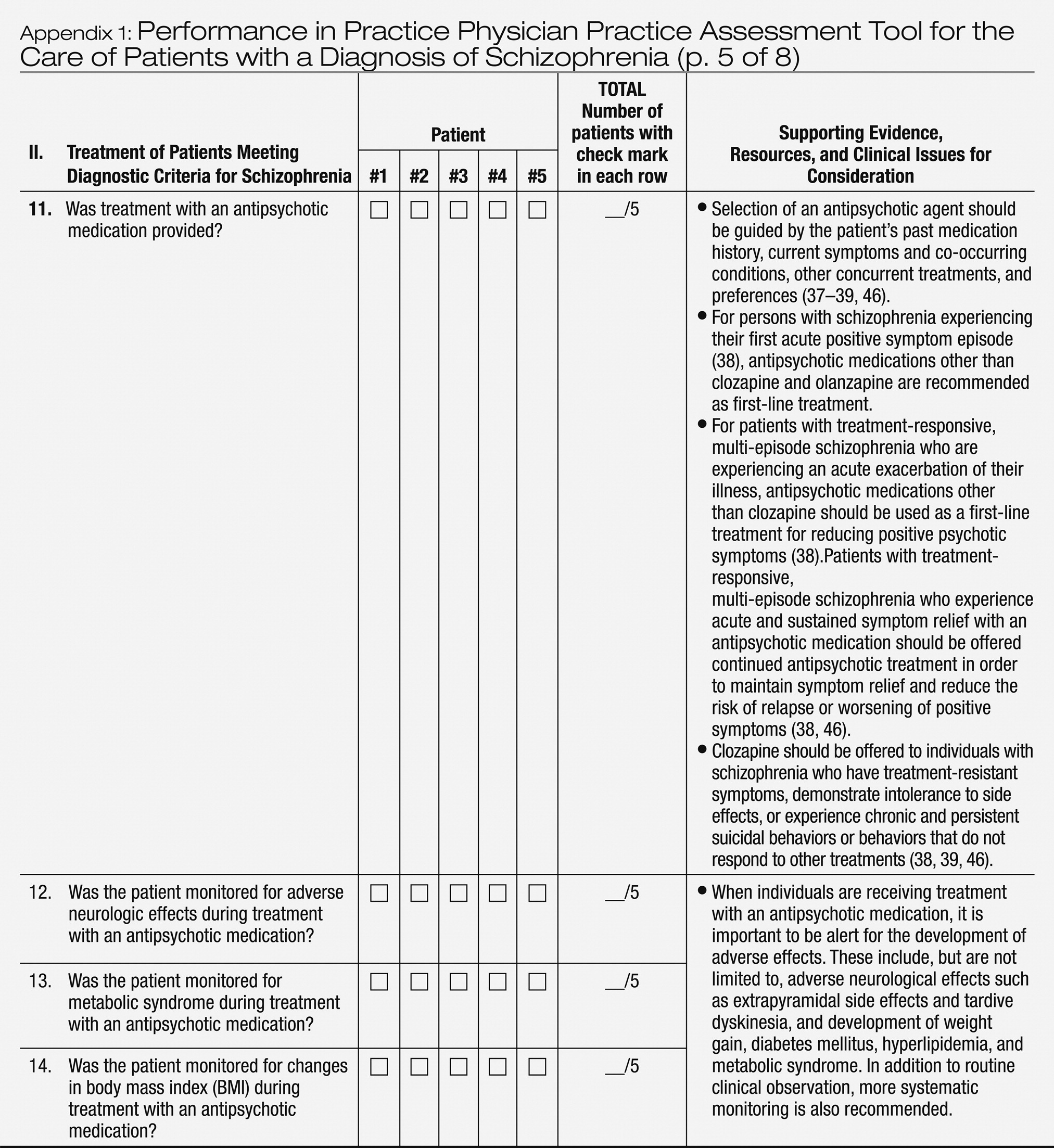

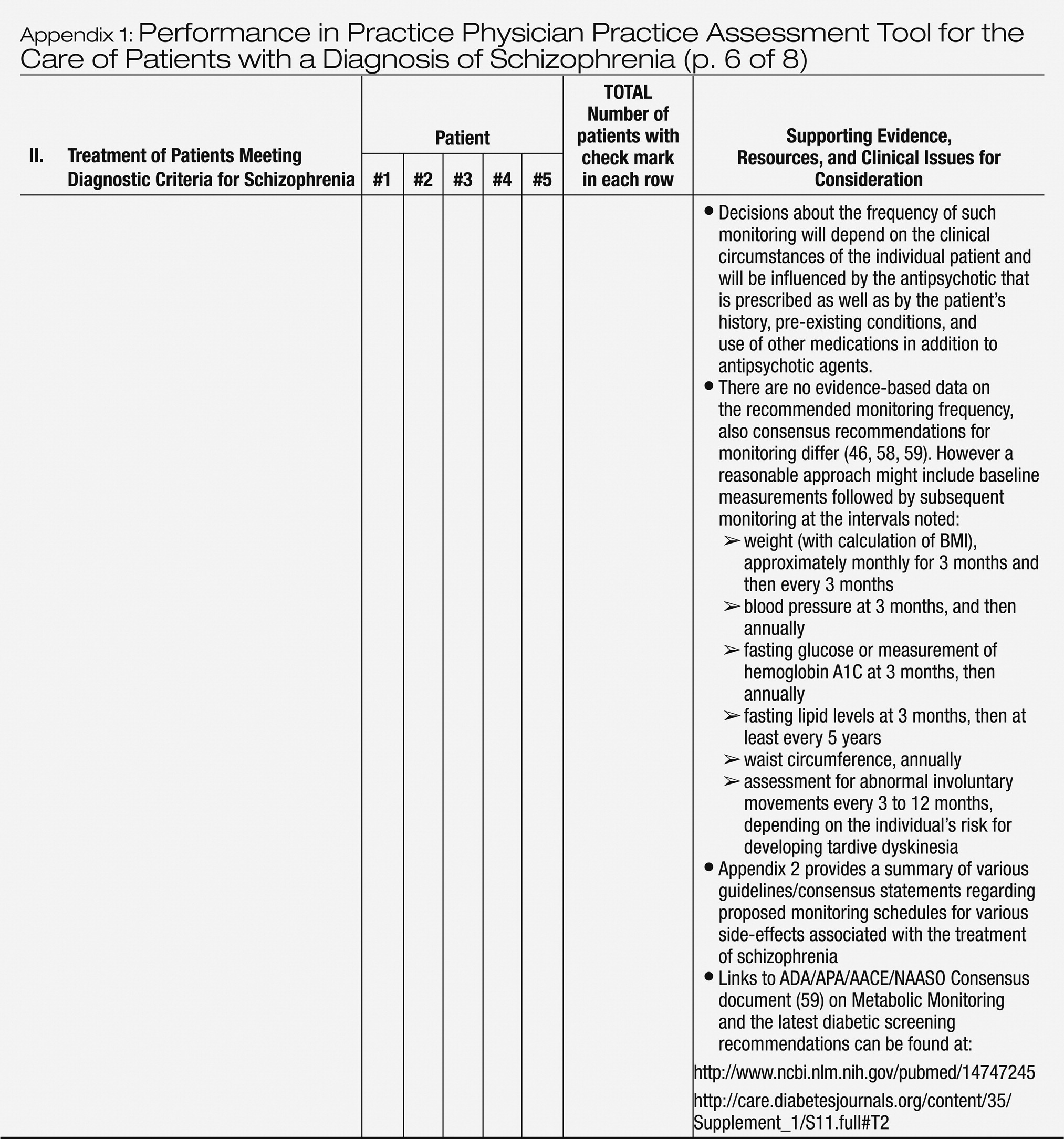

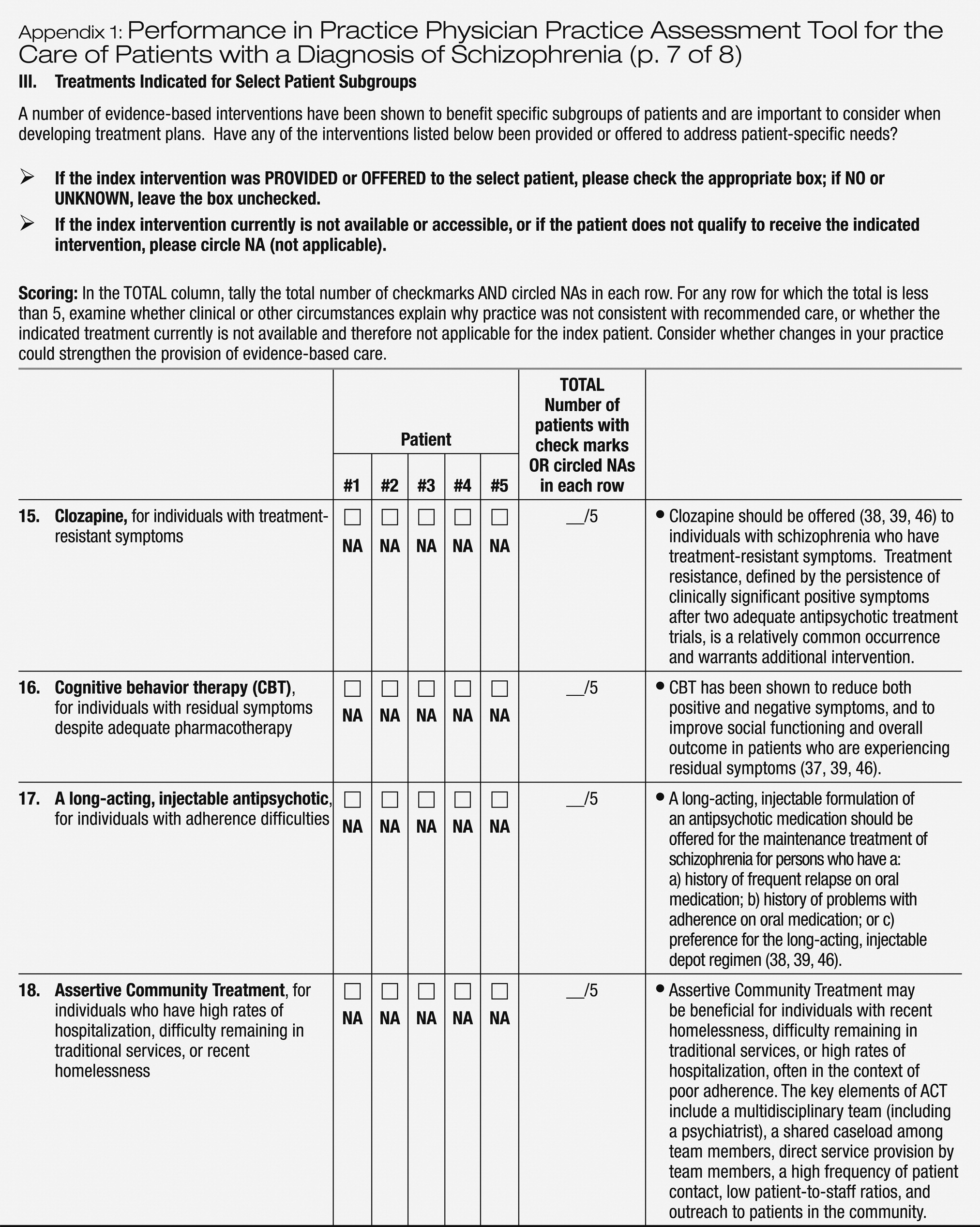

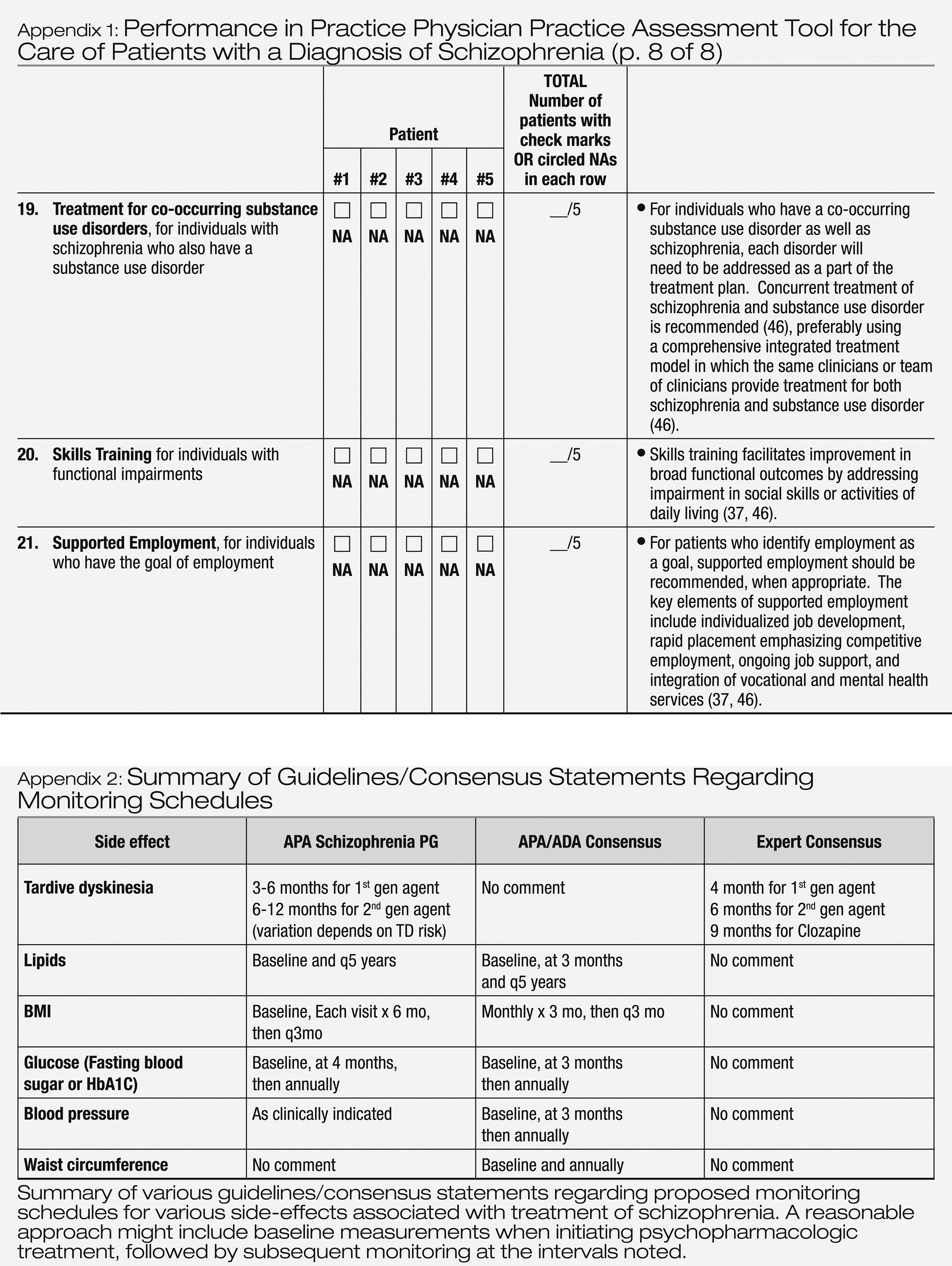

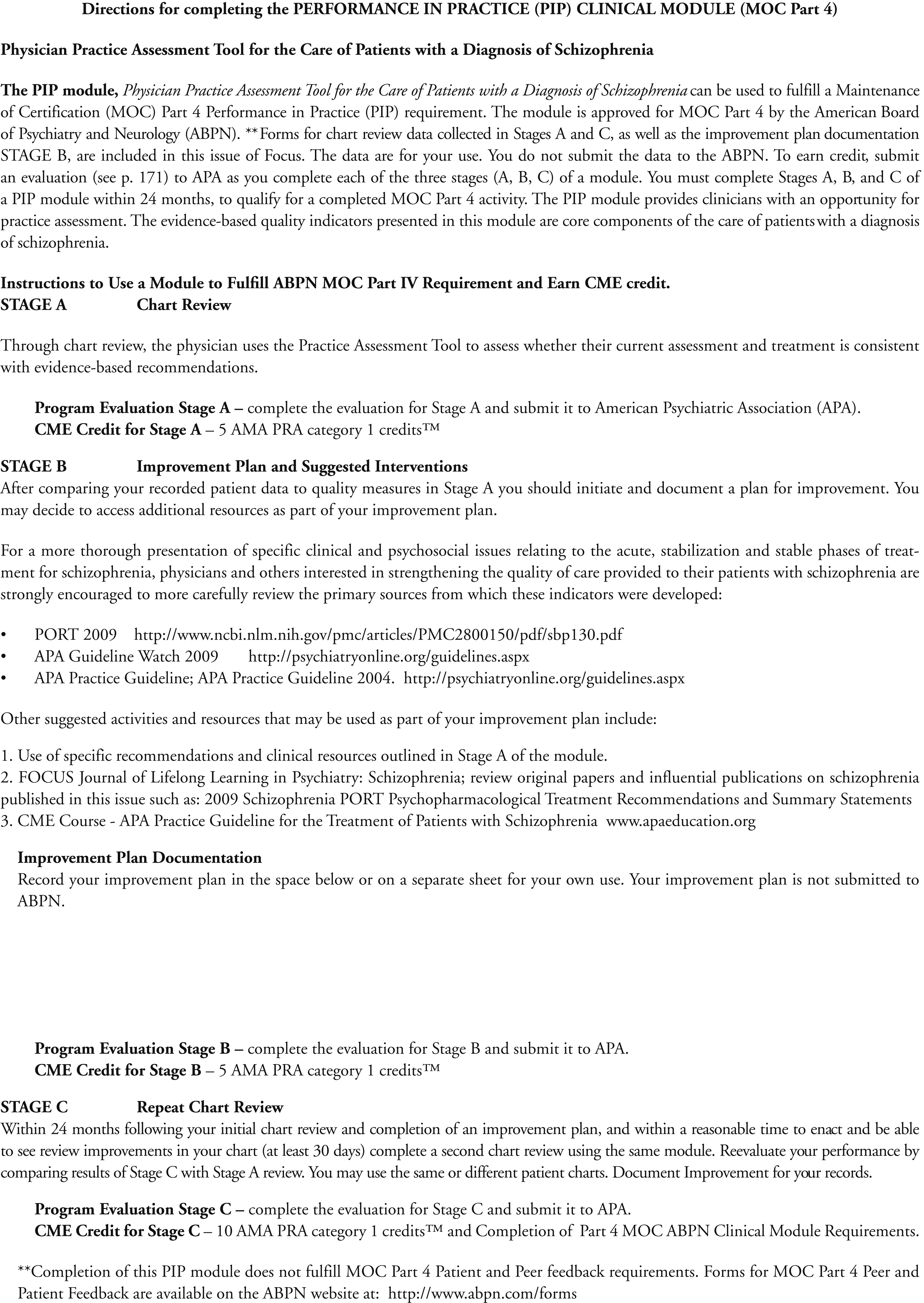

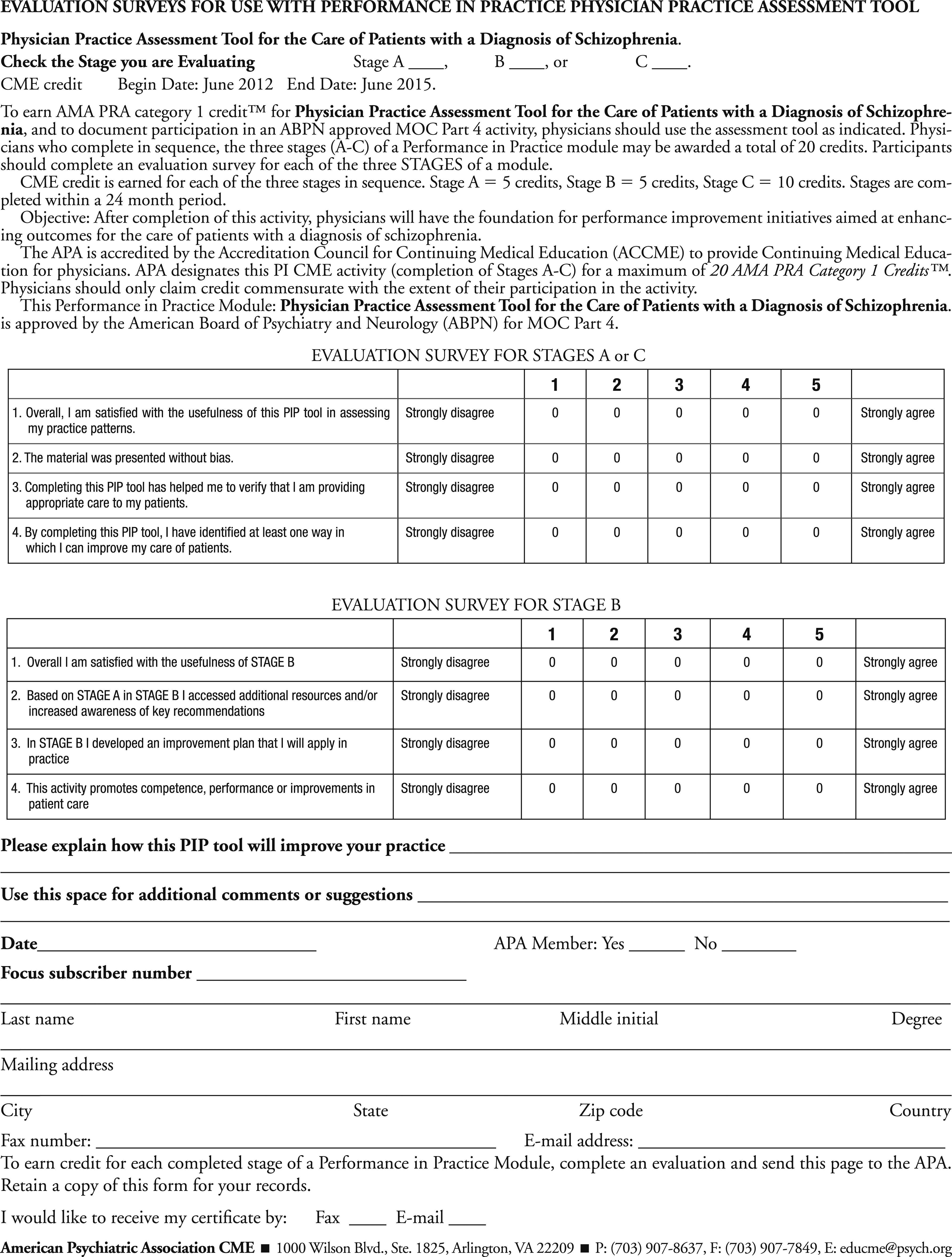

Given the high levels of morbidity, mortality and social burden of disease and suffering associated with schizophrenia, the Performance in Practice (PIP) Physician Practice Assessment Tool for the Care of Adults with Schizophrenia presented in Appendix 1, was developed to help meet the new ABMS and ABPN MOC requirements and to assist psychiatrists in optimizing care to patients. This PIP tool is also intended to: 1) Provide a simple retrospective chart review tool for physicians to examine the care provided to adult patients with schizophrenia to determine whether the clinician’s current assessment and treatment practices are consistent with the latest evidence-based recommendations; and 2) Offer key evidence-based recommendations and valuable clinical resources related to screening, assessment, treatment interventions, and possible ways to improve clinical practice.

The first step in developing this PIP tool involved identifying clinically significant evidence-based assessment and treatment recommendations from the following sources: the American Psychiatric Association’s (APA’s)

Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia (

9); the APA’s “Guideline Watch: Practice Guideline for the Treatment of Patients with Schizophrenia” (

37); and the Schizophrenia Patient Outcomes Research Team (PORT) (

38,

39). The evidence-based guidelines were developed through systematic medical literature reviews and critical evaluation of the scientific research by experts in the assessment and treatment of schizophrenia. The Guideline Watch (

37) is a more recent review of the literature that provides an update for the published APA guideline (

9). The PIP tool presented here is based on a synthesis of information from these sources and provides evidence-based measures that relate to the assessment and treatment of schizophrenia.

The PIP tool presented in Appendix 1 includes three sections related to: 1) patient assessment; 2) general treatment approaches; and 3) treatments that are indicated for specific patient subgroups. Each section highlights aspects of care that have significant public health implications, or for which gaps in guideline adherence are common, for example, use of long-acting injectable antipsychotics for individuals with antipsychotic adherence difficulties, or use of cognitive behavior therapy for individuals with residual symptoms despite adequate pharmacotherapy. The core assessment and treatment recommendations highlighted in sections 1 and 2 of Appendix 1 generally can be managed by individual psychiatrists and applied as a part of their routine practice, rather than relying on other health care system resources. The last column of the tool provides guideline-supported recommendations and clinical resources to assist in practice improvement efforts.

This PIP clinical tool has been designed to be relevant across different clinical settings; is straightforward to complete; and is usable in a pen-and-paper format to aid adoption. In addition to its value as a self-assessment tool, this form could be also used for retrospective peer-review initiatives. Although the ABPN Maintenance of Certification program requires review of at least 5 patients as part of each PIP unit, it is important to note that larger samples will provide more accurate estimates of quality of care within a practice.

After using the PIP tool to assess the pattern of care provided to patients, the physician should determine whether specific aspects of care need to be improved. Through such practice assessment, the physician may determine that deviations from the quality indicators are clinically appropriate and justified, or he or she may choose to acquire new knowledge and modify his or her practice to improve quality. For example, if patients with schizophrenia in the physician’s current psychiatric caseload are not routinely screened for tobacco or alcohol use, then an area for improvement could involve implementation of systematic screening for alcohol and tobacco use, which are especially common among patients with schizophrenia.

It is important to note that while this tool is intended to highlight current evidence-based assessment and treatment recommendations for patients with schizophrenia, justifiable variations from recommended care may occur. Assessment and treatment recommendations provided in the practice guidelines are generally intended to be relevant to the majority of individuals (

40,

41). However, patients vary widely in their preferences for treatment, clinical presentation, history of treatment and prior response, presence of comorbid physical and psychiatric conditions, and other factors that may influence clinical decision making. Because patients with schizophrenia often have high levels of complex symptomatology and co-occurring psychiatric and other general medical comorbidities, divergence from evidence-based recommendations may occur. Deviations from guidelines may also arise because of treatment nonresponse to adequate trials of antipsychotics, a relatively common occurrence in clinical practice due to the limited efficacy of the antipsychotics that are currently available (

42,

43). In addition, practice guidelines and quality indicators are often derived from findings of efficacy and effectiveness trials in which stringent enrollment criteria are used; thus individuals in clinical trials often differ in important ways from those seen in routine clinical practice (

44).

For a more thorough presentation of specific clinical and psychosocial issues relating to the acute, stabilization and stable phases of treatment for schizophrenia, physicians and others interested in strengthening the quality of care provided to their patients with schizophrenia are strongly encouraged to more carefully review the primary sources from which these indicators were developed:

The APA guideline in particular presents a treatment approach emphasizing that, as a chronic illness affecting all aspects of a person’s life, treatment planning for patients with schizophrenia should have three goals: 1) reduce or eliminate symptoms, 2) maximize quality of life and adaptive functioning, and 3) promote and maintain recovery from the debilitating effects of illness to the maximum extent possible. The source guidelines highlight critical issues related to these treatment goals which are not fully reflected in the quality indicators presented here, including the importance of establishing a therapeutic alliance in order to identify barriers to the patient’s ability to participate in treatment and engage the patient’s family members and other significant support persons.

The PIP tool in Appendix 1 provides clinicians with an opportunity for practice assessment in preparation for the new 2014 ABPN Maintenance of Certification program requirements. Because the evidence-based quality indicators presented here are considered core components in the care of patients with schizophrenia, use of this tool can serve as a foundation in developing a systematic approach to practice improvement for the assessment and treatment of patients with schizophrenia. Use of the PIP tool will likely highlight potential treatment services gaps, which may include, for example, lack of availability of cognitive behavioral therapy, Assertive Community Treatment, substance abuse treatment services, or Supported Employment programs. It is hoped that this tool, together with the evidence-based guidelines underlying these clinical recommendations, may be useful in advocating for increased availability of critically needed core services to help improve the lives and functioning of individuals with schizophrenia. With Health Care Reform (i.e., the 2010 Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act) bringing promising new services delivery models and systems such as Accountable Care Organizations and Health Homes, it is an opportune time for clinicians and advocates to draw attention to the importance of availability of the full array of evidence-based services and treatments for care of patients with schizophrenia as well as other psychiatric disorders.