Children and adolescents

Practice guidelines for the treatment of ADHD have been developed by a number of working groups, including the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry (

27), the American Academy of Pediatrics (

35), the British Association for Psychopharmacology (

36), the Canadian ADHD Resource Alliance (

37), the European Network for Hyperkinetic Disorders (

38), the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (

39), and the National Institutes of Health (

40). All of these practice parameters stress the importance of a multimodal treatment approach to patients with ADHD.

Multimodal treatment of children and adolescents with ADHD includes careful treatment planning, psychoeducation, medication, behavior management, school-based interventions, family therapy, and social competence training. While the precise combination of these interventions will vary depending upon the needs of the patient and family, it is clear that no single treatment approach is sufficient, and that in order to be effective, treatment must extend over long periods of time

Treatment planning needs to incorporate patient/family priorities and available resources and identify potential obstacles to successful treatment adherence. In addition, systems issues must be taken into consideration so that professional helpers can form constructive relationships with patient/family, school personnel, key community supports, and with one another in order to maximize chances for successful treatment.

The goal of psychoeducation and counseling is to help parents and youth cope better with the consequences of having ADHD. Patients/families need reliable information and supportive guidance when confronted with the diagnosis of ADHD. It is important that the clinician offer the patient and family sufficient time to discuss their concerns and answer their questions. Factual information should be provided in a comprehensible fashion so as to clarify any misunderstandings or confusion about the disorder. The clinician should emphasize the child’s positive traits and the parents’ strengths in order to alleviate feelings of guilt, confusion, and anger. While parents are likely to be relieved to hear that their child’s problems are not the result of inadequate parenting, they are also likely to experience grief reactions as they learn more about the implications of the diagnosis. While children may be pleased to hear their problems are not their fault, they are also likely to feel ashamed and resentful about having “something wrong” with them, and they may resist taking their medication or participating in behavioral treatment. It is important for the physician to monitor the emotional reactions of parents and children, and to be supportive of their efforts to pursue treatment. There are numerous references written for parents that are very helpful in explaining the diagnosis and treatment of ADHD, which are available on websites sponsored by the Centers for Disease Control, National Institute of Mental Health, and CHADD (Children and Adults with Attention Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder. These include resources like the Parents’ Medication Guide for ADHD, coauthored by the APA and the AACAP [see website listings in Reference section]. Support groups for parents of children with ADHD have proliferated in recent years. These groups hold meetings, sponsor lectures, publish newsletters, and offer emotional assistance to families. Clinicians should be familiar with local chapters of CHADD and similar organizations and should have their contact information readily available for patients and families.

Pharmacotherapy

At present, there are numerous FDA-approved medical treatments for ADHD (

Table 4). While medications have been shown to provide short-term benefits for children and adolescents with ADHD, longitudinal studies in-dicate that pharmacotherapy is only one aspect of treatment and that without behavioral inter-ventions, the child’s difficulties at home and at school are likely to persist. The decision to use medication is mediated by several factors, including the child’s age, severity and profile of the child’s symptoms, comorbidity, and parental attitudes. Children under 5 years of age are less likely to respond to medications and are at greater risk of having adverse side effects, suggesting that behav-ioral interventions are an important first step with this age group (

41). School-aged children with moderate to severe symptoms of inattention and distractibility (with or without impulsivity and hyperactivity) are extremely likely to benefit from medication. Children with mild symptoms are also likely to benefit, although it is usually preferable to initiate behavioral treatment prior to starting medication with this group. The presence of other disturbances such as tics, anxiety, aggression, or depression tends to influence the choice of phar-macologic agent. Finally, parental attitudes are extremely important to consider when recom-mending medication. Most parents are ambivalent about starting their child on medication, so it is best to give them ample time to consider the decision carefully. The following guidelines are suggested when instituting a medication regimen:

1.

Specify the target behaviors that the medications are intended to ameliorate. Where possible, measure the behaviors; otherwise, use parent and teacher rating scales.

2.

Obtain baseline laboratory measures such as CBC, serum electrolytes, and liver function tests.

3.

Begin with low doses, increase gradually, and aim for the lowest effective dose possible.

4.

Follow side effects closely, and discontinue the medication if no positive effects are seen or if side effects become severe.

5.

Discuss the child reactions to and parents’ feelings about the medication. Give support and encouragement if initial results are not as good as expected.

6.

Document beneficial and adverse effects on a regular basis.

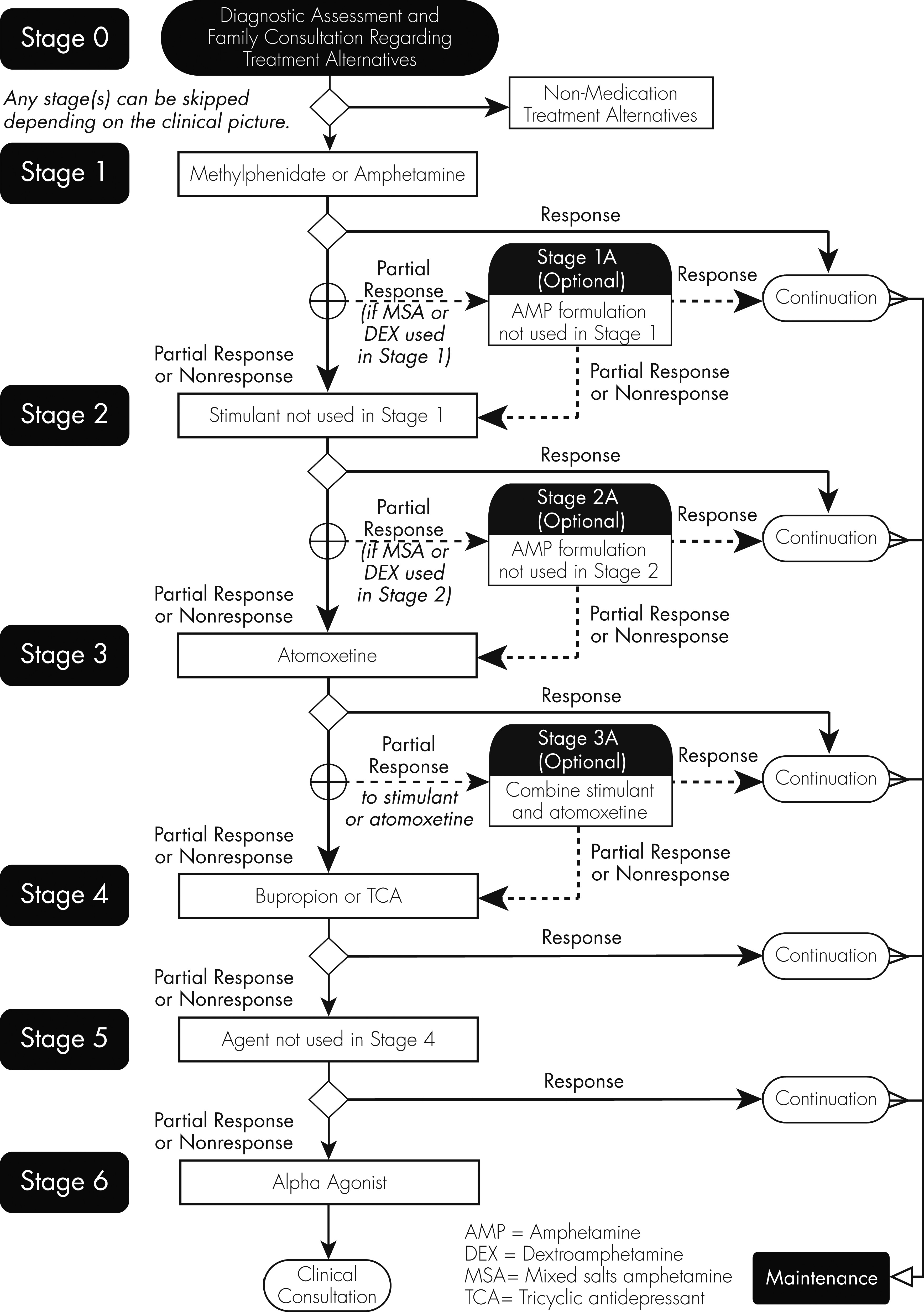

Algorithms have been developed to guide the selection of medication regimens according to best available evidence (

42), most of which suggest that clinicians initiate treatment with a stimulant medication and only if there is insufficient response should alternative medications be introduced (

Figure 2).

Psychostimulants

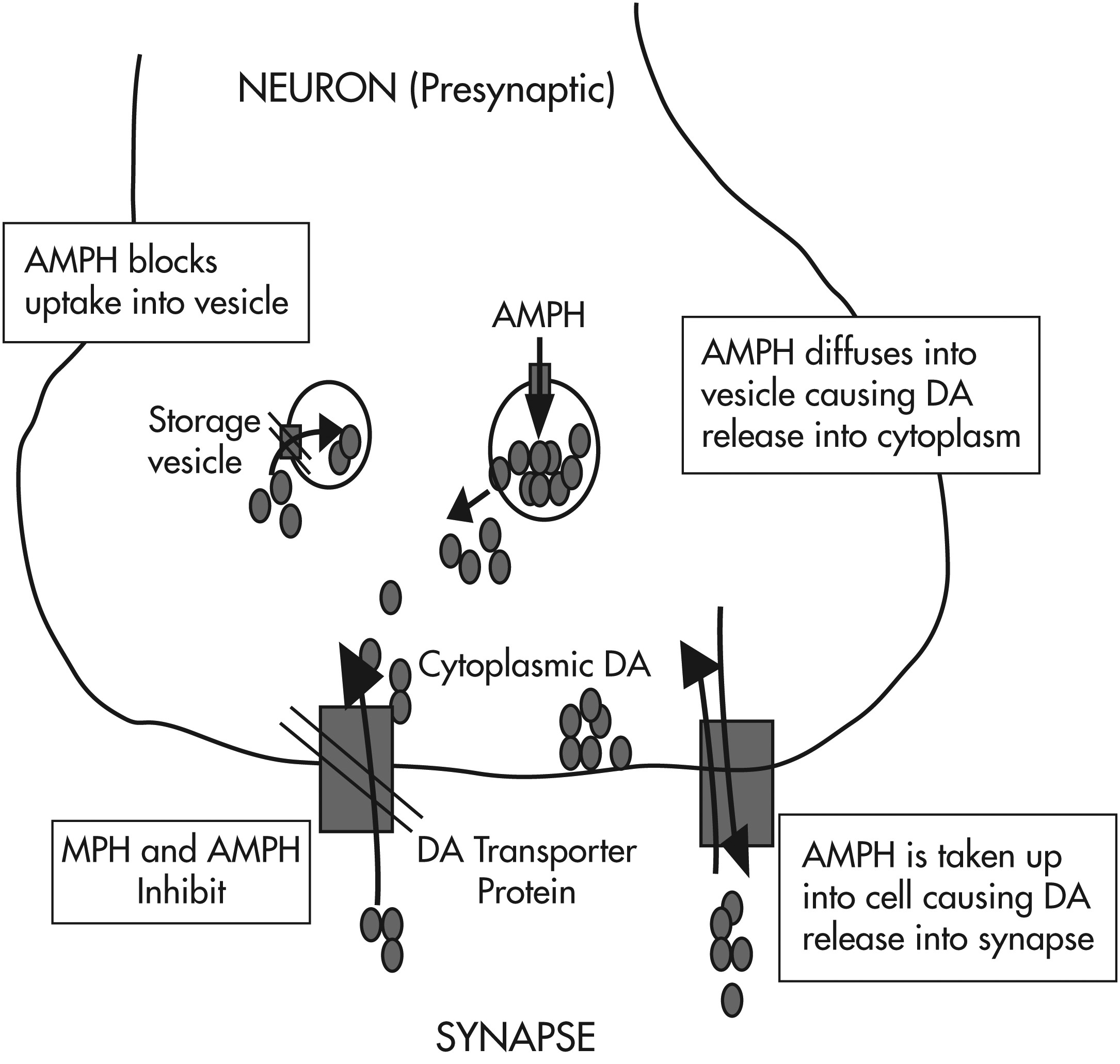

Psychostimulants have direct and indirect agonist effects on ∂-adrenergic and β-adrenergic receptors as well as on dopaminergic receptors via three mechanisms: release of stored catecholamines (dopamine and norepinephrine); agonist effects on postsynaptic receptors; and inhibition of presynaptic reuptake of released catecholamine (note: methylphenidate works primarily via mechanism 3, whereas amphetamine works via all three mechanisms [see

Figure 3]).

Over 80% of patients with ADHD demonstrate a positive response to psychostimulants, although it is impossible to predict in advance which medication will produce the best results for any given patient. Clinical effects include reduced hyperactivity and impulsivity, improved attention and concentration, improved fine motor skills (including handwriting), and improved social interactions (e.g., reduced oppositional behaviors). Behavioral measures of cognitive performance with psychostimulants demonstrate improvements in attention span, impulse control, short-term memory, and problem solving. These results are seen in both patients with ADHD and controls, so a positive response cannot be used to diagnose ADHD. In general, while cognition of ADHD patients can be optimized by the medication, this improvement can be eradicated with improper dosing.

Up to 5% of patients will experience adverse effects serious enough to warrant discontinuation of the medication. Adverse effects include appetite suppression, gastrointestinal discomfort, sleep disturbance, increased heart rate and blood pressure (clinically insignificant), tics, and minor physical complaints (e.g., headaches, stomach-aches). Irritability, dysphoria, heightened anxiety, lack of spontaneity and over-sedation may be seen, but these are often due to overmedication. It appears that a subgroup of patients who respond with intense mood lability and dysphoria may be expressing early signs of a mood disorder rather than ADHD. This should prompt a change in medication and close monitoring (

43,

44).

Extremely serious side effects such as delusions, paranoia, and frank psychosis are rare but can be seen with over-dosage and abuse of the medication. Concerns have been raised about cardiovascular side effects of stimulants, although recent reports seem to indicate that there are few, if any, serious adverse cardiac events due to stimulant use (

45,

46). Current recommendations include careful screening for cardiac symptoms in the patient (e.g., dyspnea, palpitations, and exercise intolerance), for abnormal physical findings, and for family history of premature deaths or significant morbidity from heart disease.

Clinical and biochemical predictors of nonresponse or adverse effects have not yet been identified, although there is some evidence of diminished efficacy of stimulants in ADHD children with symptoms of anxiety (

42). On the other hand, it appears that stimulants are helpful in reducing the aggressive behavior of conduct disordered ADHD children. There are also studies suggesting that stimulant treatment in childhood and adolescence reduces the risk of later alcohol or substance abuse.

Discussions with parents and teachers are helpful to identify any incipient problems with stimulant medication. It is also important to decide upon the type and frequency of medication use. For example, most long-acting medications are sufficient to improve concentration during the school day, but an additional dose of a short-acting preparation is often prescribed to help the child complete homework assignments in the late afternoon and early evening. Weekend dosing assists ADHD children with participation in team sports, social events, church activities, and instructional programs. It also enables them to complete homework assignments and study for examinations. For teenagers who drive, weekend dosing is essential to minimize the risk of hazardous driving and accidents.

After several weeks on a steady dose and schedule, it may be necessary to increase the dose slightly. The goal of treatment should be symptom remission, which often necessitates steadily titrating the dose upward until either symptoms improve or significant adverse effects emerge. If there is no clear positive response to the initial stimulant chosen, or if side effects emerge that might interfere with adherence as the dose is increased, it is advisable to introduce other stimulant preparations before additional pharmaceutical agents are introduced. Using parent- and teacher-report rating scales to track symptom response to medication can be very helpful. Above all, it is important to continuously monitor progress toward target goals and to adjust the medication regimen accordingly.

For the most part, children can be maintained on the same dose for up to 6 to 12 months. It is important to monitor clinical and adverse effects on a regular basis. Height, weight and blood pressure measurements and a brief physical examination should be conducted approximately every 2 months if things are going smoothly. If the child begins losing weight, the dose and schedule should be revised in order to optimize appetite around mealtimes. Growth delay, although rarely seen with current dosage recommendations, is an indication for stopping the medication for several weeks to allow “catch up” growth to take place.

One of the most common problems seen with stimulants is referred to as “rebound.” This is generally seen in the late afternoon as the medication wears off. Typically, the child becomes restless, hyperactive, inattentive, irritable, and prone to temper tantrums and emotional outbursts. It is often helpful to add an additional slightly lower dose when the child returns from school. Parents should be advised to allow the child to do something enjoyable and to avoid making too many demands on the child during this time. If the rebound period becomes extremely difficult for the child and family to handle, it may be necessary to switch medications or introduce longer acting preparations.

Atomoxetine

Atomoxetine is the first nonstimulant medication to be FDA approved for the treatment of ADHD. A norepinephrine (NE) reuptake inhibitor, it has been shown to have a moderate effect size (0.4 – 0.6) in numerous studies involving children, adolescents and adults with ADHD (

47,

48). The advantages of atomoxetine are its milder side effects profile (compared with stimulants), and the absence of potential for abuse or misuse. Increased CNS NE levels resulting from this medication are associated with downstream increases in dopamine (DA) levels in the frontal cortex without concomitant changes in levels found in the nucleus accumbens or the basal ganglia (

49,

50). Recent studies suggest that atomoxetine may be helpful in patients with comorbid anxiety (

51), and/or tic disorders (

52). An open trial of atomoxetine in children and adolescents with dyslexia showed improved reading task performance (

53). Side effects include: dizziness, high blood pressure, headache, irritability, nervousness, abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, loss of appetite, weight loss, dry mouth, constipation, urinary hesitancy, decreased sexual desire and a very slight chance of reversible hepatic insufficiency.

Alpha-adrenergic agents (Clonidine, Guanfacine)

Alpha2 adrenergic agonists were first introduced as antihypertensive agents over 40 years ago but were supplanted by other medications (e.g., calcium channel blockers) with fewer side effects. Their effects on the CNS include modulation of the tonic and phasic activity of the locus coeruleus (major source of NE in the brain) and enhanced adrenergic activity in the prefrontal cortex. Their effects on NE neurotransmission occur via up-regulation of intracellular cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP) which, in turn, improves signal conduction along the axon (

54,

55). Clonidine works on alpha2A, 2B, and 2C re-ceptors (which are located throughout the CNS, including the brain stem), leading to its producing more hypotensive and sedative effects than guanfacine, which is selective for the alpha2A receptors. Extended release clonidine has been found to help ADHD symptoms either alone (

56) or in conjunction with psychostimulants (

57). Clinical trials of extended-release guanfacine have shown it to be effective as monotherapy for ADHD in children and adolescents (

58–

60). Recent studies have shown guanfacine can be combined with stimulants to produce enhanced clinical effects in children and adolescents with suboptimal response to stimulants alone (

61,

62).

Clinical experience with these agents suggests that they are especially useful in reducing irritability, overarousal, emotional lability, and explosiveness in patients with ADHD. They are also helpful in controlling tics and managing high blood pressure. The most common side effects seen with alpha2 adrenergic agonists are sedation, fatigue, dizziness, syncope, cardiac rhythm disturbances, dry mouth, indigestion, nausea, nightmares, insomnia, anxiety, dysphoria, and depression. In addition, hypertensive crises can be induced by sudden discontinuation of these medications.

Psychosocial Interventions

Whereas youth with ADHD have trouble controlling their impulses, focusing their attention and following rules, parents need to learn basic methods of managing these challenging behaviors. Using techniques such as positive reinforcement, rewards, response cost, pun-ishments, contracts, token economies, extinction procedures, environmental manipulation and stimulus controls, parents can be taught to exert a positive influence on behavior.

The first step in developing a behavior management program is to specify which behaviors are acceptable and which ones need to be modified. It is important that parents learn to focus more of their attention on the child’s positive behaviors, and to “catch them being good” as often as possible. By shifting more energy and attention to the child’s “good” behaviors, parents and teachers will inevitably spend less time harping on the “bad.” Next, parents choose a specific behavior (or behavior sequence) that they would like to change. They should describe the behavior in ways they can observe and measure. It is generally best for parents to begin by focusing on a relatively simple behavior which is easy for the child to perform and for the parents to observe and quantify. Behaviors like getting ready in the morning, doing homework, putting toys away, completing chores, temper tantrums, and getting ready for bed are good for starters. It is also important for them to consider factors that prevent the child from successfully completing tasks.

Once a target behavior is chosen, parents will need to identify ways to increase the child’s motivation to cooperate. Rewards should be given for successful efforts, and penalties should be given for overt resistance or major oppositional behavior. An accounting system must be set up to keep track of the child’s performance and to distribute the rewards and penalties in an impartial fashion. It is important that parents not get angry or upset with the child when they are administering a penalty. After parents have decided upon the rewards and penalties, it is advisable for them to draw up a contract. The contract should include the date on which the agreement begins, the specific behaviors that are being targeted for change, the types of rewards and penalties that will be used to enforce the contract, the accounting system that will be used to keep track of rewards and penalties, the time and frequency of rewards, the start and duration of penalties, and the schedule for reviewing the contract. The contract should be written in a language that the child can understand, and should be posted in a prominent place in the home. Once it has been discussed and reviewed, the contract should be signed by everyone who will be involved in its enforcement (including other adults).

After the contract becomes operational, its efficacy will need to be closely monitored, and its terms will need to be refined and corrected in order to ensure that it is helping the child to achieve desired behavior changes. The child should succeed at the desired behaviors 80% of the time. If s/he is succeeding more often, the task should be made more difficult; if less, it should be made easier.

It should always be kept in mind that the purpose of any behavior management system is to help the child learn to follow rules and to complete important tasks. This is a major challenge for most children with ADHD, and parents will need to work very diligently to keep a behavior management program running. Although it takes a great deal of patience, resourcefulness and perseverance, parents can look forward to modest rewards for the child and the family. If the program succeeds in improving the child’s ability to care for him/herself and in increasing his/her self-control, it will have the added benefits of reducing stress and improving the emotional climate of the family.

Classroom behavioral interventions have been developed to improve both classroom deportment and academic performance. The best studied have been daily report cards and contingency management programs with effect sizes in the range of 1.44 (

63). Classroom academic interventions seem to have moderate beneficial effects, although these are not as well studied and sample sizes are small. The most common interventions include task and instructional modification, homework assistance, peer tutoring, computer-assisted instruction, and strategy training (for an excellent review, see (

64)). More recent innovations include family-school interventions that promote close collaboration between parents and teachers in order to achieve improved academic performance and classroom behavior (

65).

Recently, computer-assisted programs have been introduced to enhance cognitive functioning in children and adolescents with ADHD. The best studied of these, CogMed, is a software program developed by Klingberg and colleagues at the Karolinska Institute. It entails web-based training on a series of rotating exercises designed to enhance visuospatial and verbal working memory, five times per week for 30-40 minutes. Initial results of randomized controlled trials show modest improvements in these domains (

66,

67).