Discussion

Corroborating prior COBY findings (

4), this study showed that bipolar spectrum disorders in youths are episodic disorders characterized most often by subsyndromal episodes and less frequently by syndromal episodes, with mainly depressive and mixed symptoms and rapid mood changes.

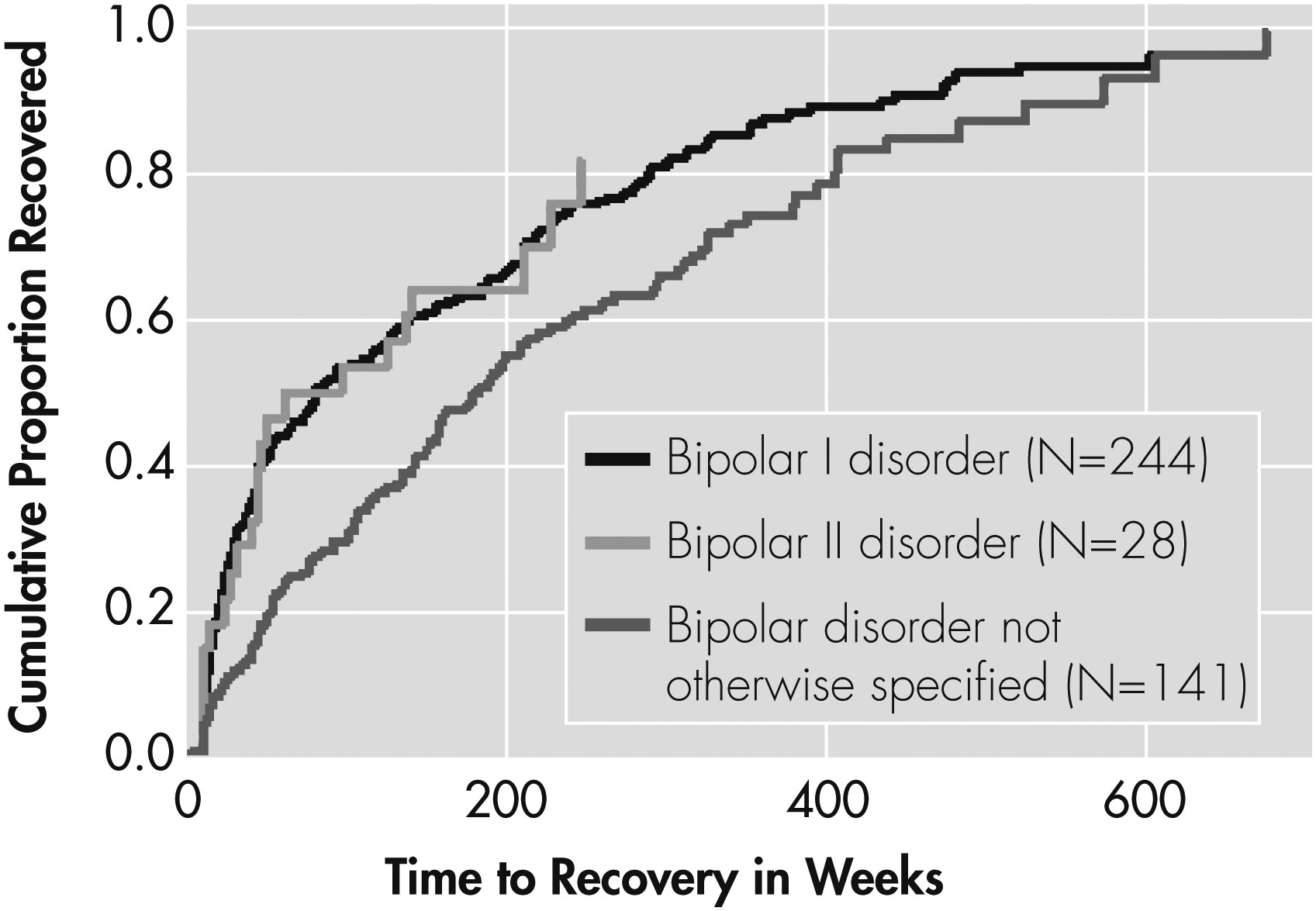

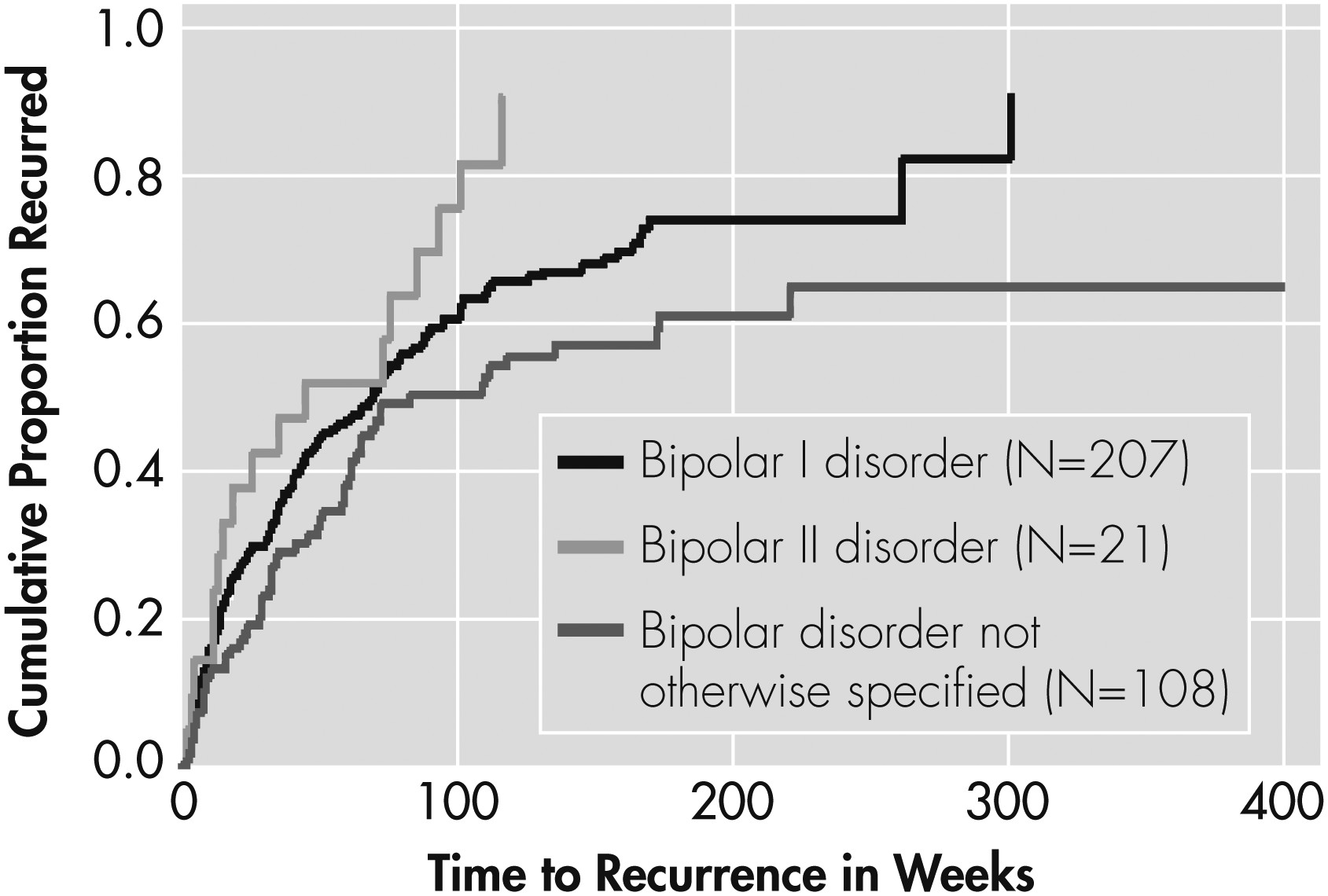

Survival analyses using the standard definitions of syndromal recovery and recurrence (based on DSM-IV and the literature) indicated that approximately 80% of youths with bipolar spectrum disorders achieved full recovery about 2.5 years after onset of their index episode. However, 1.5 years after full recovery, approximately 60% of the participants had at least one syndromal recurrence. Compared to youths with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified, those with bipolar I and II were more likely to recover but also to have a less durable recovery.

During the entire follow-up period, one-third of the participants had at least one syndromal recurrence and 30% experienced more than two syndromal recurrences. Most of these syndromal recurrences were major depressions, followed by hypomanic, manic, and mixed episodes. In general, the polarity of the index episode predicted the polarity of subsequent episodes.

In addition to the analyses focusing only on recovery and recurrence of syndromal symptoms, week-by-week analyses provided a more in-depth clinical picture of the course of bipolar disorder, showing that distinct periods of full syndromal mood episodes exist in youths with bipolar spectrum disorders. However, these episodes are embedded in more prevailing and longer periods of subsyndromal mood symptomatology. Youths with bipolar spectrum disorders were symptomatic during 60% of the follow-up period, during which they spent about 2.5 times more time with subsyndromal than with syndromal symptomatology. Mixed/cycling and depressive symptoms accounted for the greatest proportion of time ill. In contrast, purely manic symptomatology, especially at the full syndromal level, was less common. Rapid mood changes were ubiquitous, and psychotic symptoms were relatively common, particularly in youths with bipolar I. Chronic symptoms, defined as having any type of symptoms during 75% or more of the follow-up period, were present in 38% of the participants. Almost all of these chronic symptoms were subsyndromal and of the depressive type.

The week-by-week analyses also shed light on the similarities and differences in the longitudinal patterns of symptom phenomenology of youths with bipolar I and II and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified. Bipolar I was manifested by more time with subsyndromal than with syndromal symptoms. Most of the syndromal time was characterized by mixed/cycling or depressive symptoms, and most of the subsyndromal time was with subsyndromal manic or mixed symptoms. Youths with bipolar II spent equal amounts of time in syndromal and subsyndromal states. The syndromal episodes were most commonly depression or mixed states, but there were no significant differences in the proportion of time spent with any type of subsyndromal symptoms. Finally, bipolar disorder not otherwise specified was mainly manifested by periods of subsyndromal mixed symptoms, closely followed by periods of subsyndromal manic or depressive symptoms.

Between-group comparisons provided preliminary validation for the subtyping of bipolar disorder in youths. In general, in comparison with other subtypes, each bipolar subtype continued to show some category-specific symptomatology. For example, during follow-up, youths whose initial diagnosis was bipolar I showed more syndromal, mixed/rapid cycling, and manic/hypomanic symptoms than did those with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; youths with bipolar II spent more time in hypomania than did those with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified and more time in depression than did those with bipolar I and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified; and youths with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified spent significantly more time with subsyndromal symptoms than did those with bipolar I and II. However, there was some symptom overlap among the different bipolar subtypes, especially bipolar I and II. Moreover, 25% of youths with bipolar II converted to bipolar I, and 38% of those with bipolar disorder not otherwise specified converted to bipolar I and II.

Although there were some differences in the demographic and clinical factors associated with the outcome variables measured (recovery, time symptomatic, and changes in polarity), in general, early onset of bipolar disorder, presence of comorbid disorders, family history of mood disorders (particularly mania/hypomania), low socioeconomic status, and non-Caucasian race were associated with worse outcome. Long duration of illness was also associated with a lower likelihood of recovery, with each year of illness decreasing the likelihood of recovery by 20%.

Before continuing the discussion of COBY’s findings, it is important to note the limitations of this study. First, despite efforts to obtain precise information, the data collected through the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Evaluation is subject to retrospective recall bias. Although it appears that this instrument has adequate psychometric properties (

1,

4,

12), further studies using the methods described by Warshaw et al. (

12) and including blind interviewers are warranted. Second, although COBY used the standard definitions of course for recovery and recurrence (

1,

3,

18), the rates and duration of the mood episodes may change according to the duration criteria and symptom threshold severity chosen. Third, the results pertaining to youths with bipolar II should be considered tentative given the relatively small size of this group. However, across all bipolar subtypes, after depression most syndromal recurrences were hypomanias. Finally, as most participants were Caucasian and were recruited primarily from outpatient and, to a lesser extent, inpatient settings, the generalizability of the observations to other populations remains uncertain. Nevertheless, nonreferred adolescents with bipolar disorder have been shown to have a similar course and high morbidity (

5).

Despite methodological differences, all existing studies of the course of bipolar disorder in youths, regardless of country and source of ascertainment, show that the likelihood of recovery from the index episode is high (

1–

4). However, as with adult populations, despite the high recovery rate, the rates of recurrence, persistence of subsyndromal clinical morbidity, and rapid and frequent changes in mood polarity are also high, and most syndromal and subsyndromal recurrences are depressions (

16,

19–

23). It does appear that the polarity of the index episode predicts the polarity of the subsequent episodes (

21,

24–

28), which suggests the possibility of using specific psychosocial and pharmacological treatments based on the polarity of the index episode.

The results of this and other emerging pediatric studies suggest strong general similarities in the longitudinal course of bipolar disorder in youths and adults, which is mainly manifested by subsyndromal symptomatology and rapid mood changes (

1–

4,

29). However, there is evidence that very early onset confers greater liability for a more chronic and fluctuating course, mixed/cycling episodes, high rates of comorbid disorders, and increased rates of mood disorders in families (

1,

3,

30–

32). Converging with these accounts are reports indicating that adults whose onset of bipolar disorder dates to childhood have a more severe and chronic course, lower quality of life, and more episodes, changes in mood polarity, suicidality, and comorbidity (

33–

35).

Comparable with other findings in the literature (

1–

4,

6), we found that childhood-onset bipolar disorder, comorbid disorders, positive family history for mood disorders, and low socioeconomic status were associated with poorer outcome. Moreover, the probability of recovery was inversely related to duration of illness, which further underscores the importance of early detection of illness and rapid implementation of stabilizing treatments. Such efforts may be of even greater urgency for youths with bipolar disorder who have risk factors associated with poorer outcome.

Similar to findings in the literature on major depression (

36), it appears that there are some differences in the factors associated with the various indices of clinical outcome (recovery, recurrence, and amount of time symptomatic). Moreover, as the polarity of the index episode was shown to convey different prognostic characteristics, it may be that these observations will be informative to clinical practice. For example, since youths with depression were seen to have more depressive recurrences, they may require more aggressive and specific therapies to reduce the risk of future depressive episodes.

To our knowledge, COBY is the first naturalistic, prospective study of this affective subtype in youths—an important avenue of research given the modal age of onset of bipolar II illness during adolescence (

18,

27,

37). Consistent with adult data on high levels of morbidity associated with this subtype, youths with bipolar II had a greater overall risk of recurrence and more depressive morbidity compared to youths with bipolar I, and had rates of nonaffective comorbidity, suicidality, nonsuicidal self-injurious behaviors, functional impairment, and family history of bipolar and other mood disorders comparable to those with bipolar I (

6,

7,

32,

38–

40). Also, bipolar II in youths appears to be a far less stable phenotype than in adults; in this cohort, 25% of the bipolar II youths converted to bipolar I, a rate higher than that reported in adult studies (

41). Since this disorder is mainly characterized by episodes of syndromal and subsyndromal depression across the lifespan, it is well appreciated that periods of hypomania can be misconstrued as normal fluctuations in mood or as erratic behavior, and perhaps more so in adolescents (

27,

42), resulting in a high risk of misclassification as recurrent unipolar depression or other, nonaffective disorders.

Bipolar disorder not otherwise specified is characterized by rates of comorbidity, suicidality, functional impairment (except hospitalizations), and family history of mood disorders equivalent to those in youths with bipolar I and II (

6,

7,

32,

38–

40). These findings, together with the high rates of conversion to bipolar I or II, provide preliminary validation of its nosological affinity with bipolar I and II disorder. It should be emphasized, however, that our classification relied on the presence of an affective phenotype that differed from bipolar I or II due to failure to meet the DSM-IV duration requirements for these subtypes. Thus, our findings are in accord with studies in the adult literature (

18,

42,

43) emphasizing the existence of clinically relevant episodes of mania/hypomania that last for less time than required by DSM criteria. These episodes are often overlooked because of the predominance of syndromal depression and subsyndromal manic/mixed symptoms of short duration in its expression. Results from COBY suggest that bipolar disorder not otherwise specified is an

episodic illness, albeit one that often comprises subsyndromal episodes that should be considered distinct from the symptomatology of youths with behavior disorders and “severe mood dysregulation” (

44).

In summary, although distinct episodes of full syndromal mood symptomatology as well as durable periods of euthymia can be identified in youths with bipolar disorder, the course of bipolar spectrum disorders in children and adolescents is predominantly characterized by subsyndromal and, much less frequently, syndromal episodes. Rapid mood changes are evident during these episodes, which are mainly of depressive and mixed polarity. During follow-up each bipolar subtype showed some distinct clinical characteristics and course, but there was overlap in their symptoms and substantial conversion from bipolar II and bipolar disorder not otherwise specified into other bipolar subtypes. The course of bipolar disorder, the relative infrequency of syndromal DSM manic episodes, the effects of development in symptom manifestation, and the high prevalence of comorbid disorders may account, at least in part, for the difficulties in recognizing and managing this illness in youths. The recurrence, chronicity, and psychosocial morbidity associated with this illness in critical developmental stages call for its prompt recognition and the development of more efficacious treatments, particularly since each year of illness appears to decrease the likelihood of recovery.