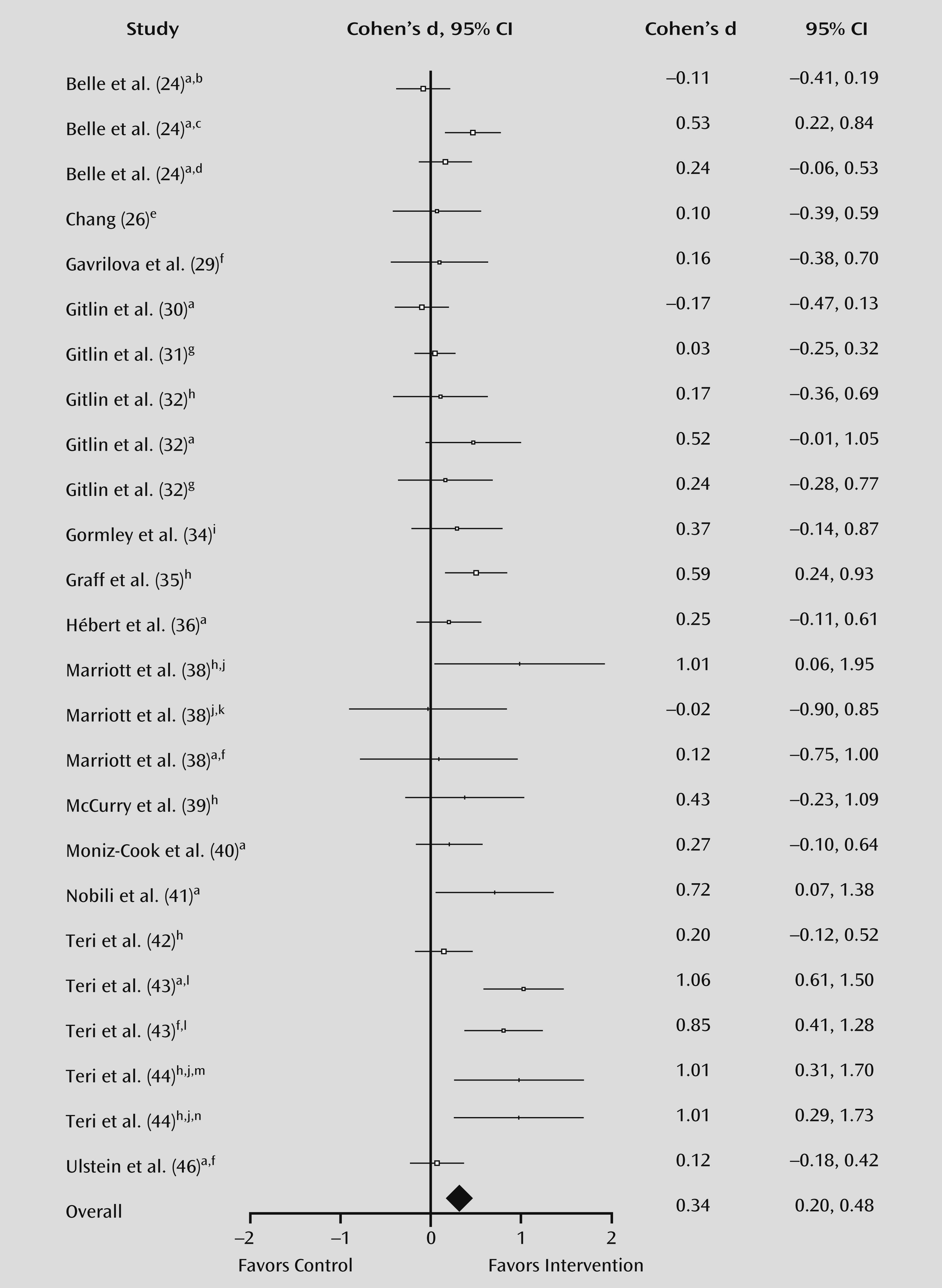

While the negative effects of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia on caregivers are well documented, there is little appreciation of caregivers’ ability to influence the occurrence and severity of these symptoms. This meta-analysis reveals that caregiver interventions can significantly reduce behavioral and psychological symptoms in the person with dementia as well as the caregiver’s negative reactions to these symptoms. Ayalon and colleagues (

18) reported that nonpharmacological interventions that addressed behavioral issues and included caregivers were more likely to be efficacious for managing behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia, but the authors stressed the need for confirmatory studies. The present review found significant benefits for behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia from high-research-quality interventions that targeted these symptoms and included the family caregiver. The availability of 23 high-quality trials from just the past two decades effectively delivering a wide range of interventions in the community indicates how the field has advanced. These effects are at least comparable to those of antipsychotics. From a report by Yury and Fisher (

47) on behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia treatment, a net effect size of 0.13 can be calculated from their findings of 0.45 (95% CI=0.16–0.74) for atypical antipsychotics and 0.32 (95% CI=0.10–0.53) for placebo. Similarly, Schneider and colleagues (

48) reported an effect size of 0.18 (z=3.43; p=0.0006) in favor of antipsychotics in the treatment of behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia. Unlike with antipsychotics, however, caregiver interventions had no adverse effects on caregivers or persons with dementia. In the only study with negative effects, behavior deteriorated over time but to similar degrees in the intervention and control groups (

26). The three studies with no treatment effects on symptoms still had other positive outcomes for caregivers, namely, a reduction in caregiver depressive symptoms (

28), a decrease in caregiver burden (

29), and an increase in caregiver general well-being (

25). Of these three studies, one (

25) had a behavior management component in both the intervention and control groups and found improvements in both groups in the measure “bother associated with care recipient behaviors.”

Limitations

Our findings are subject to several limitations. First, the use of multicomponent strategies and omnibus behavior rating scales prevented identification of which specific elements of interventions were effective for which behaviors. Second, not all interventions targeted behaviors; for example, Chang (

26) focused on care generally. Third, the choice of instruments may have mitigated demonstration of effects. For example, about a third of the items in the Revised Memory and Behavior Problem Checklist concern activities of daily living, a third depressive symptoms, and a third other behaviors. Even if interventions had significant benefits for nondepressive behaviors, these effects would have been diluted by the nonbehavioral items. Fourth, caregivers’ variability in knowledge, skills, and supports prior to intervention affect their capacity for improvement. Where outcomes were adjusted for caregivers’ scores on these variables at baseline, those with the lowest scores benefited the most (

37). For example, in phase 2 of the Resources for Enhancing Alzheimer’s Caregiver Health study of three different ethnic groups, the Latino-Hispanic group may have benefited significantly more because the intervention was provided in Spanish and may have been the first time participants had received such assistance (

24).

Fifth, the quality of research and sample sizes varied. While there is clearly room for improvement, the cost of such trials and the difficulty in recruitment of representative samples of caregivers and people with dementia are considerable. Sixth, nonpharmacological intervention studies appear to recruit patients with less severe behavioral disturbances than do drug trials and usually exclude psychotic patients. Seventh, a limitation of nearly all pharmacological and nonpharmacological studies is the reliance on reports of behaviors, which may be biased, rather than on direct observation. Finally, for many of the interventions, we were unable to calculate the effect size or the sustainability of outcomes. Of the 10 studies that reported follow-up (

29,

35,

37–

39,

41–

44,

46), symptomatic and/or related caregiver improvements were maintained in eight studies (

35,

37,

39,

41–

44,

46).

Implications

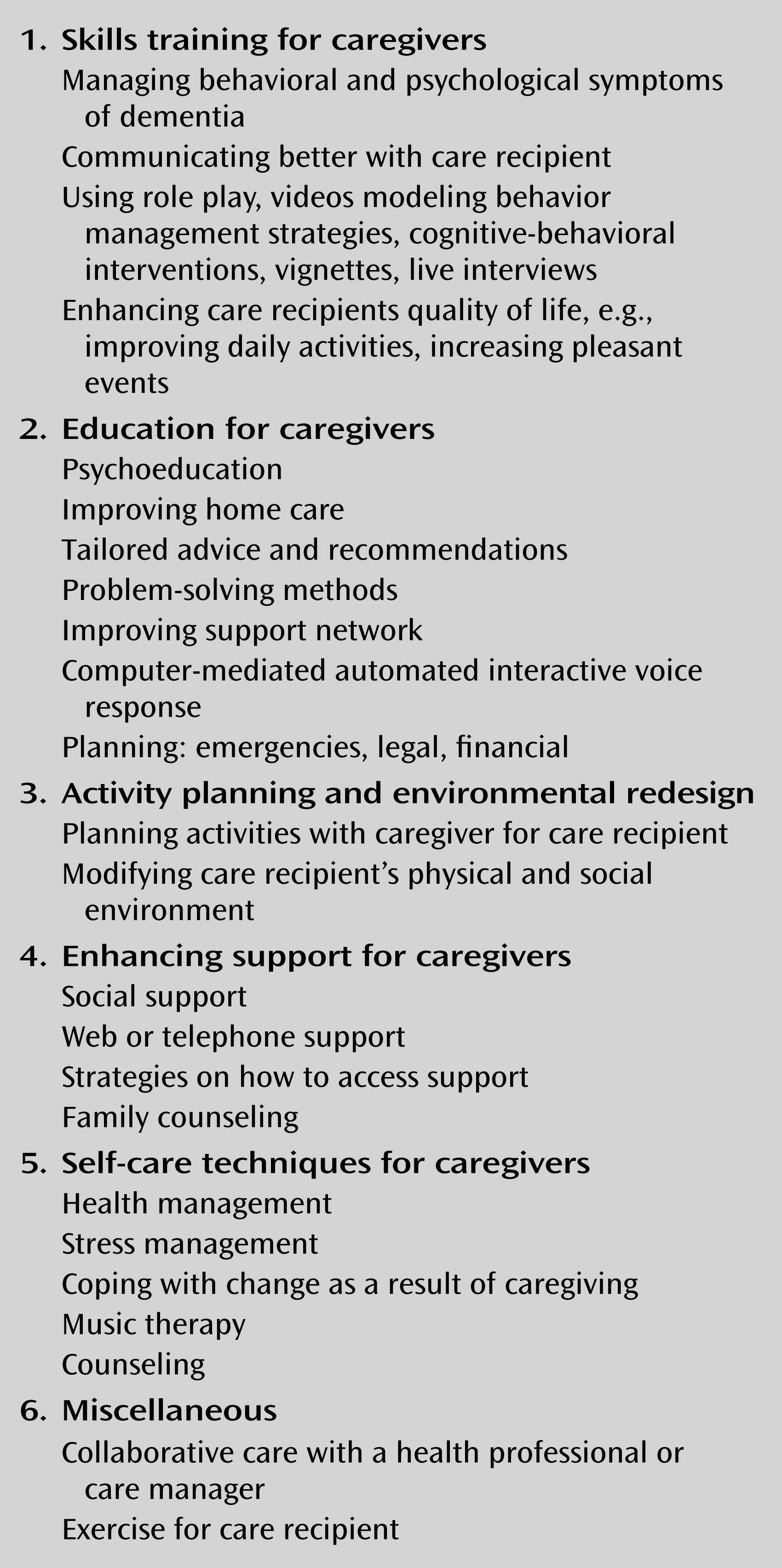

Fine-grained questions regarding which elements of interventions are effective for which behavioral and psychological symptoms of dementia delivered by which caregivers to which persons with dementia require further attention. Questions about the optimal duration, frequency, and setting of interventions cannot be answered empirically from these data. Successful interventions included approximately nine to 12 sessions tailored to the needs of the person with dementia and the caregiver and were delivered individually in the home using multiple components over 3–6 months interspersed with telephone sessions and subsequent individual or group telephone follow-ups. Behaviors more likely to respond to such interventions appear to be agitation, aggression, disruption, shadowing, depression, and repetitive behaviors rather than psychosis. From the emerging pattern for success, we recommend adopting interventions that are multicomponent, tailored to the needs of the caregiver and the person with dementia, and delivered at home with periodic follow-ups.

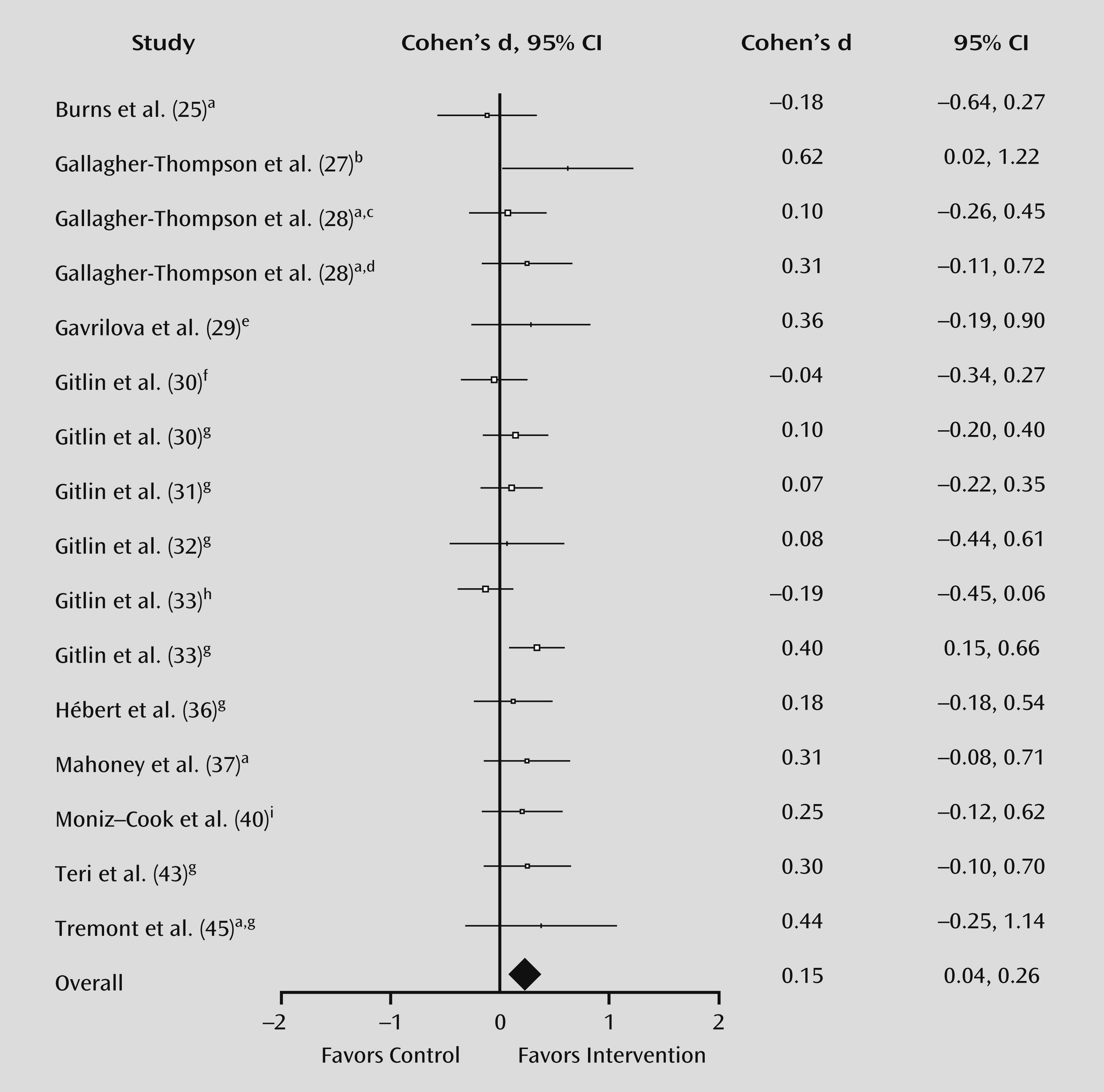

The implications from this meta-analysis are extensive. For policy makers, our findings suggest that supporting programs to work with caregivers would be an efficient and potentially sustainable model. For clinicians, caregivers, and persons with dementia, there is a preference for trying nonpharmacological approaches first and avoiding or delaying the use of medications, which have the potential for serious adverse effects and high attrition (

9). Despite the onus assumed by caregivers in these interventions, caregivers reported significant benefits to their own psychological health (

24–

28,

30–

33,

35,

37,

38,

40,

43,

44), general health (

35,

38), general well-being (

25,

31,

33), overall quality of life (

24,

35), caregiving burden (

29,

33,

43,

45), and caregiving skills (

30–

32,

40,

41). For researchers, our findings suggest numerous questions that require investigation; in addition to those outlined above, information about cost-benefit and delay in institutionalization will be persuasive in advocating for funding for such interventions. Systematic reporting of sufficient data to allow comparative analysis should be complemented by at least one follow-up to test sustainability.