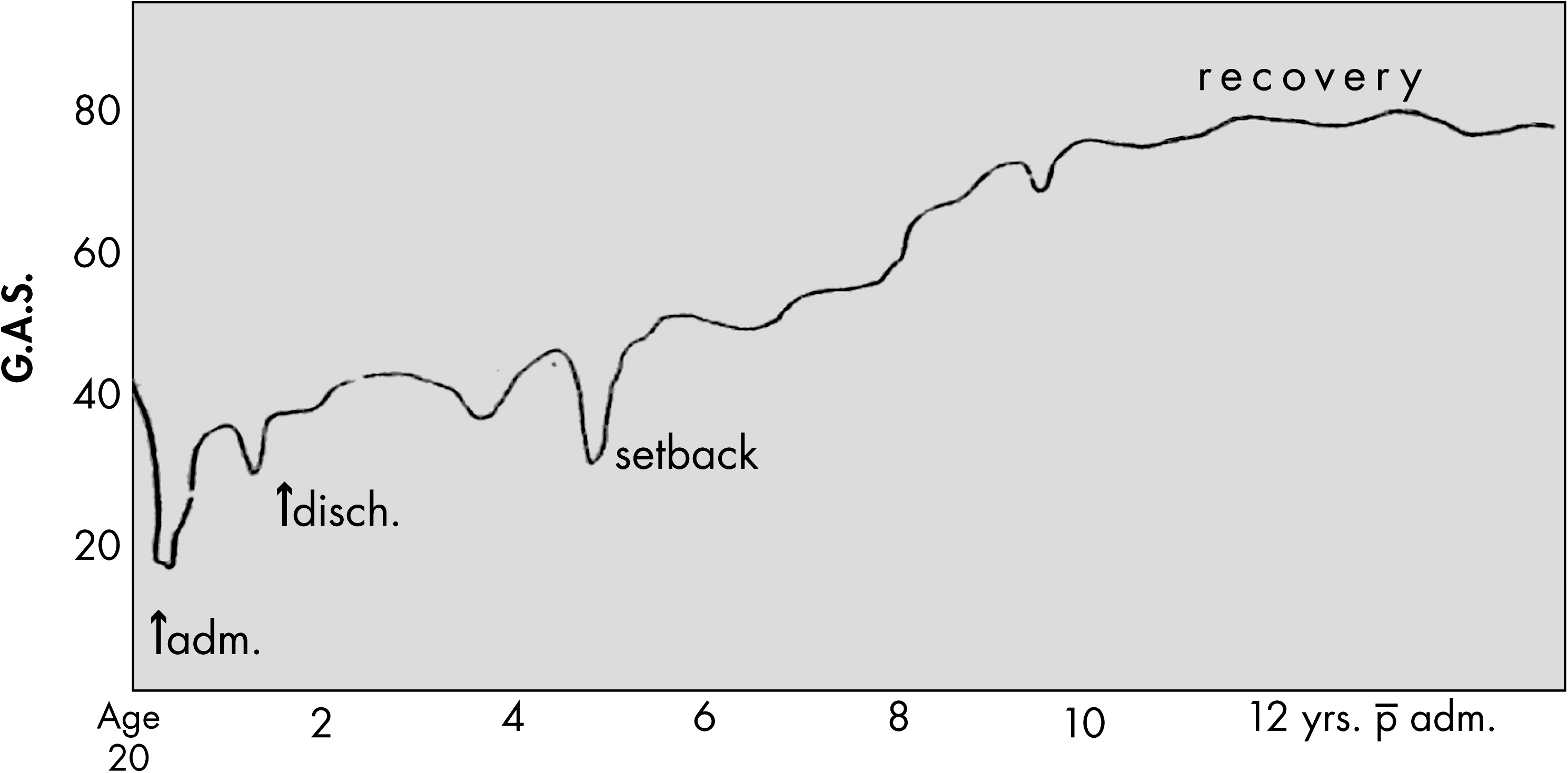

The course of BPD had been considered very gloomy until research shed light on it. One reason for this was the excessive attention given to the subgroup of BPD patients who were repeat visitors to emergency rooms and inpatient units, the so-called “frequent flyers”. This impression called into question by an original series of research studies that deployed follow-back strategies, i.e. getting in touch with patients who had previously been in treatment at a given institution (

53–

55).

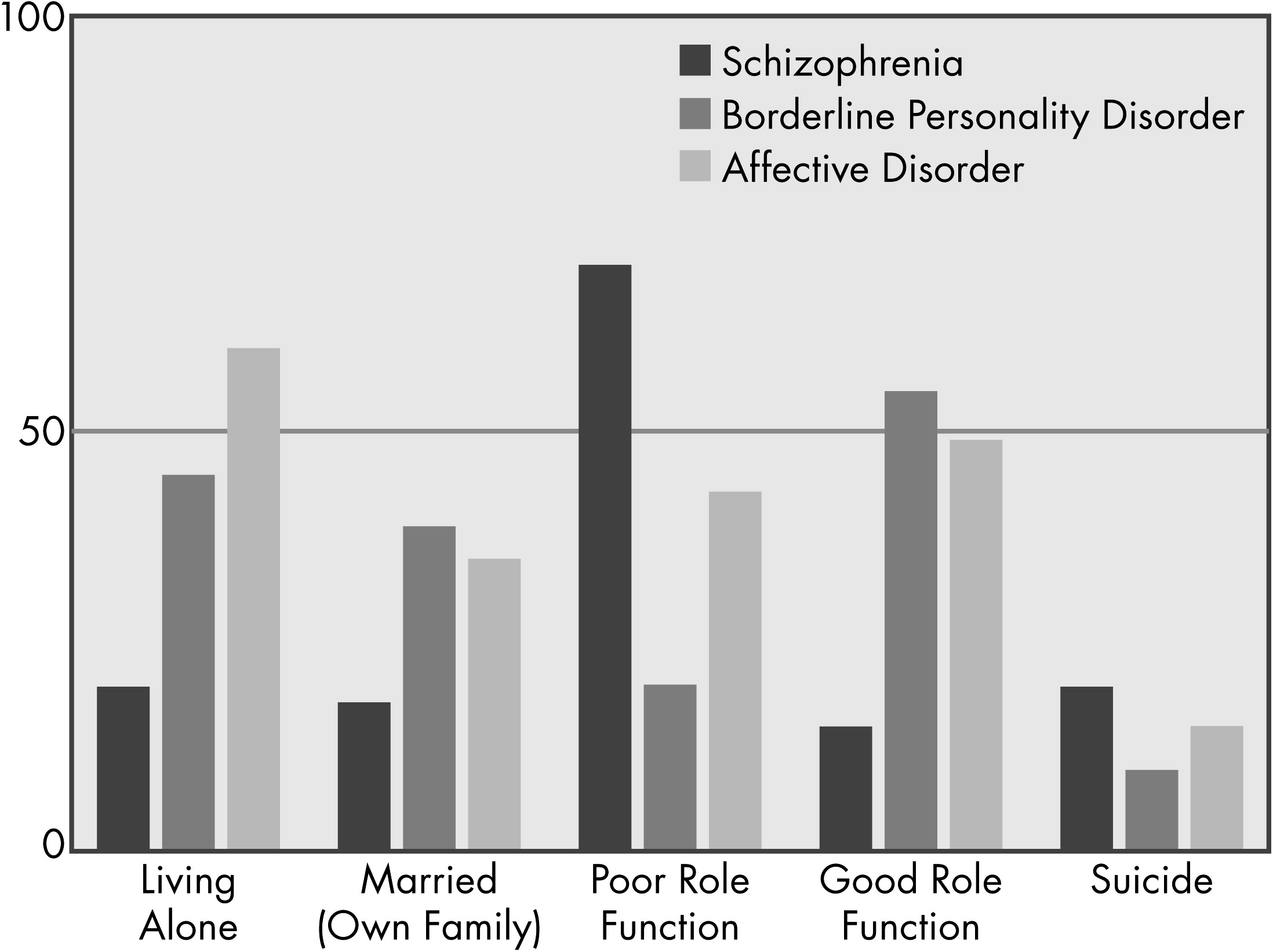

Figure 2 and

3 indicate what was found. Generally, the results showed gradual improvement in psychopathology and a better course than schizophrenia though worse than depression. Because these results were attained from high-income populations, were often from high-prestige institutions using different and sometimes unstandardized assessments and, above all, were retrospective, these results had uncertain credibility.

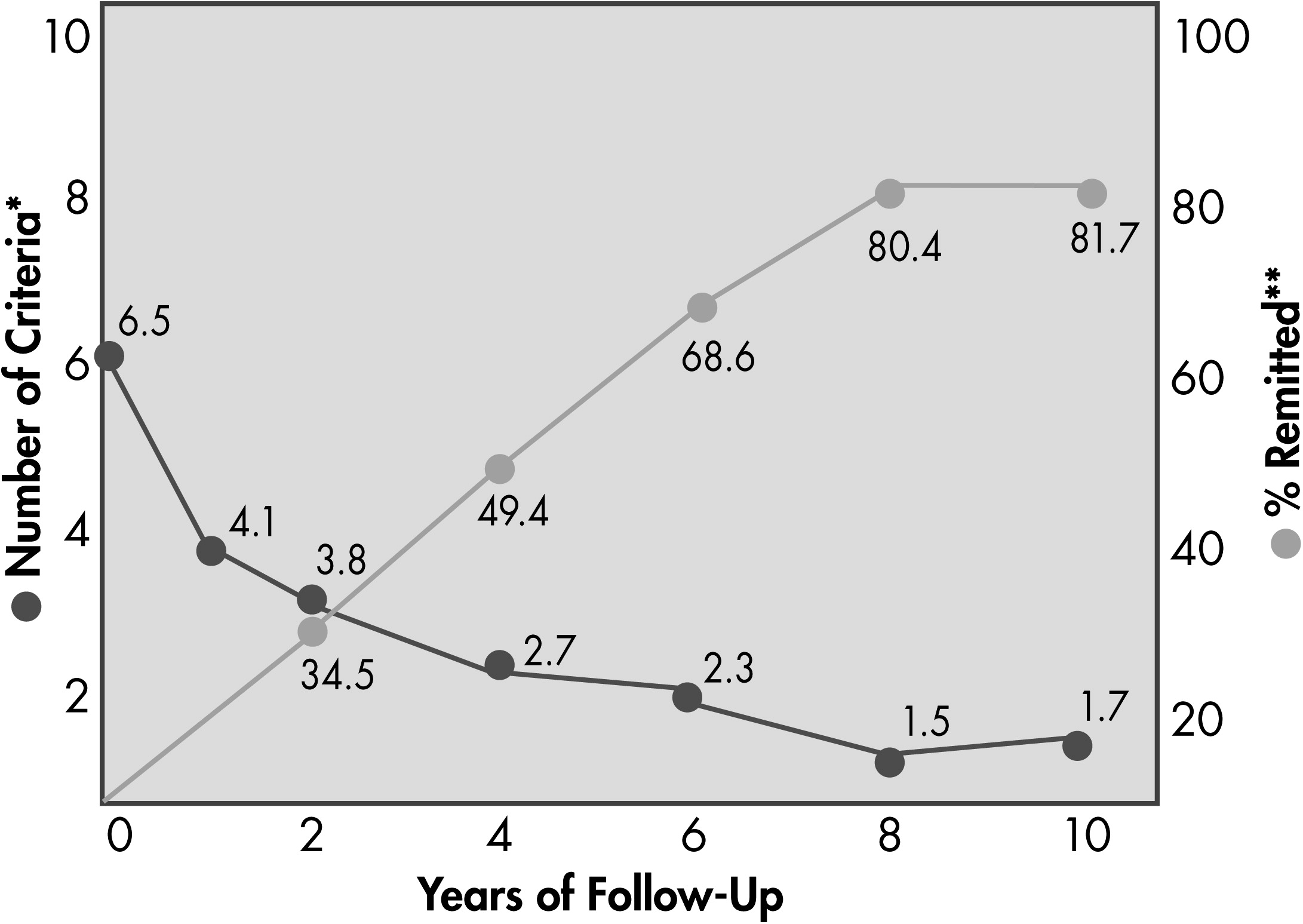

The methodological limitations of the earlier longitudinal studies were addressed in two prospective studies, the McLean Study for Adult Development (MSAD) and the Collaborative Longitudinal Personality Disorder Study (CLPS). Both were NIMH-funded and were initiated in the 1990s with many results that have been published in recent years.

Table 4 summarizes some of their design and methodology characteristics. Of note, while the CLPS stopped after 10 years, the MSAD continues to collect data with the most recent reports having 16 years of follow-up. This review will first discuss the course of BPD psychopathology, then social functioning, and then mediators/moderators.

Course of Social Functioning

A far more discouraging picture of BPD’s natural course emerged from the examination of social adaptation. The GAF scores of BPD samples remain quite low (about 65) (

60), and the rate of those receiving disability support remains quite stable (about 40%) (

61). At 10 years follow-up about 30% are married or have stable partnerships and a similar fraction have full-time vocational activities (

60). As grim as this seems, the group mean scores for the BPD sample rose significantly on subscales such as self-satisfaction, recreation, and friends. Moreover, these group means hide a considerable amount of variance within the BPD samples and within any particular individual BPD person. Zanarini found that the subsample on disability at 10 years was comprised mainly by a subsample who were not on disability originally (

61)! In a longer-term 16-year follow-up, Zanarini has recently reported that 60% of her McLean Hospital-based sample has “recovered,” a term that combines both persisting remission with sustained partnerships (

59). This report offers a more hopeful perspective about sustained and substantive changes than have prior reports.

Mediators and Moderators of Course

As described elsewhere (see the “Biopsychosocial Underpinnings” subsection), borderline patients have a neurophysiological system that is primed to make them stress responsive. The longitudinal data support this. Their remissions frequently occur when they leave highly stressful situations (

62). This explains why they can regain their composure and sociability so quickly when placed in low stress asylum-like situations. Of note, they report having more stressful events, most particularly interpersonal stressors like rejection, that precede and predict self-harm, suicidality, dissociation, and relapses (

63–

65).

Predictors of outcome were identified as well. Higher degree of BPD psychopathology, low functioning, and history of childhood sexual abuse predicted slower symptomatic recovery in CLPS (

66); older age, childhood sexual abuse, family history of substance use, and poor vocational functioning predicted slower symptomatic recovery in MSAD (

67). Some of these predictors are probable moderators (e.g., childhood sexual abuse) whereas others are probable mediators (e.g., low functioning) of the course, though more research is needed to examine these hypotheses.

Longitudinal data cannot tell us much about the effects of treatment but they do document the high utilization of health care resources and the gradual reduction of expensive resources like emergency rooms and hospitals (

68,

69). They also document the heavy utilization of medications and especially polypharmacy by borderline patients. The more medications, the worse the course. This probably reflects both overreliance on medications despite their modest effects and that a downhill course evokes more prescription of medications.

Examinations of

comorbidity are clinically instructive. Of particular importance is that while effects of MDD on BPD course seem to be negligent, BPD has a highly negative effect on the course of MDD (

70), a disorder that co-occurs in about 75% of borderline patients. On the other hand, comorbid cluster B personality disorders, notably antisocial and narcissistic types, seems to slow BPD recovery (

67). Results regarding effects of comorbid PTSD are inconclusive (

66,

71).

Biopsychosocial Underpinnings

Our understanding of the etiology of BPD has become increasingly complicated, accommodating the influences of not only biology and environment separately, but also the interaction between the two. Earlier etiological accounts of BPD, influenced by prevailing psychoanalytic theory, emphasized early environment or experiences, such as trauma, in the development of BPD. As research on BPD has specified biological factors associated with phenotypic features of the disorder, modern etiological formulations have focused on constitutional factors, associated to distinct genetic and neurophysiological characteristics. This review will consider the early developmental, genetic, and neurobiological factors implicated in the development of BPD, as well as the incorporation of these underpinnings into clinical formulations that have organized its major treatments. In each area, the recent advancements from research are impressive, yet readers should also note that while the research often differentiates BPD from healthy controls, the more demanding designs that would demonstrate specificity, vis-a-vis BPD’s major border disorders (MDD, bipolar disorder, and PTSD) usually still need to be conducted.

Early Development

Early psychoanalytic conceptualizations of BPD identified difficulties with separation from caretakers as a central developmental failure in BPD (

72). Both insecure attachment and traumatic separation experiences were theoretically implicated as pathogenic factors contributing to the clinical observation of abandonment fears in BPD (

73). These clinical theories prompted empirical investigations that confirmed the association between early caretaking experiences, such as more frequent separations and parental over- or under-involvement, and the diagnosis of BPD (

74–

76). Subsequent studies specifically demonstrated higher prevalence of sexual abuse in subjects with BPD compared with subjects without BPD, leading to a theory that sexual abuse specifically—and childhood trauma more generally—was a main etiological factor in the development of the disorder and that BPD may be better conceptualized as a chronic or complex form of posttraumatic stress disorder (

77,

78). While studies continued to confirm the increased prevalence of childhood trauma among individuals with BPD, they also showed that childhood trauma is neither “necessary or sufficient” for the development of BPD (

79), nor accounts for much of the amount of variance in the etiology of the disorder (

13,

80,

81).

Prospective longitudinal studies have now clarified that while abuse is significantly associated with personality disorders in general (

82) and BPD in particular (

83), other environmental and parental factors also contribute significantly to BPD’s development. These include low socioeconomic status, family disruption, life stress, maternal inconsistency in the presence of over-involvement, aversive or hostile parental behaviors, and low parental affection (

82–

84).

In addition to discrete environmental and parental factors contributing to the etiology of BPD, the nature of transactional process between individuals and caretakers, as codified in attachment styles, have been implicated in the development of BPD. Multiple cross-sectional studies of adult samples with BPD and at least one prospective study have documented the predominance of insecure attachment styles, particularly a combination of preoccupied, disorganized, and fearful styles (

83,

85–

87). The preoccupied aspects of this combination of styles confers the needy, over-involved, angry, and passive qualities to interactions between individuals and caretakers, whereas the disorganized or fearful aspect captures the contradictory, confused, mistrustful, and disoriented qualities of such interactions. Taken together, these two styles interact to both perpetuate attachment interactions through high levels of involvement as well as potentiate distress and emotional challenge. It is likely that the interaction between these styles heightens vulnerability to adverse caretaking interactions and impairs use of attachment for its regulatory effect.

Genetics - In establishing the genetic basis of BPD, a number of family studies of BPD demonstrated a degree of familiality of the disorder (

88). They indicate that the mean prevalence of BPD in first-degree relatives is 11.5%, much higher than in the general population (see Epidemiology section). However, these family study findings could not in themselves differentiate the proportion of etiological variance contributed by genetic and environmental factors (already outlined above). Torgersen and colleagues used twin samples to establish concordance of 35% in monozygotic (MZ) twin pairs and 7% in dizygotic (DZ) pairs, with genetic modeling suggesting additive genetic effects ranging from 0.57 to 0.69 and shared-in-family environmental effects ranging from 0–0.11 (

89). Another twin study examined the heritability of component traits of BPD indicated heritability of 45% for affective lability, 49% for cognitive dysregulation, and 48% for insecure attachment (

90,

91). Since then one large family and two twin studies assessed the heritability of the component sectors of BPD and used multivariate modeling to determine whether there is a single common latent genetic factor in BPD. They found a range of heritability from 44%–60%, with the remaining variance contributed by individual specific environmental factors (

18,

60,

92). This level of genetic influence exceeds the heritability of anxiety disorders and depression, but is less than that of bipolar affective disorder or schizophrenia.

Findings from the limited research on

molecular genetics of BPD indicate associations between polymorphisms in genes relevant to the serotonergic and dopaminergic system (see Chanen & Kaess [

84] for review). Because polymorphisms in the serotonin transporter gene (5-HTTLPR) have previously established a relationship with affective lability (

93), impulsivity (

94), and suicide (

95) it has been of most interest. However, there remains only limited evidence of the relationship between this polymorphism and BPD, and positive results are inconsistently replicated (

84).

Specific predisposing early environmental factors in the etiology of BPD combine with genetic factors to confer varying degrees of vulnerability to the development of BPD. As described above, early childhood adversity in a number of forms, constituting “life stress” in general, contribute to the development of BPD. Recent genetic studies have considered the gene-environment interactions of sensitive genotypes and predisposing environments related to a number of disorders. Functional length polymorphisms of the serotonin transporter gene has been shown to moderate the depressogenic effects of stressful life events (

96,

97). In studies of BPD, this short allele polymorphism appears to moderate the effects of stressful life events by decreasing impulsivity (

98). Moreover, the genetic influences that contribute to the development of BPD also increase the likelihood of exposure to specific stressful live events (

99). In addition, genetic influence effects stress reactivity (

100), making some people more likely to develop symptoms following traumatic stress (

101). Therefore, while important to distinguish the unique contributions of environmental and genetic forces contributing to the etiology of BPD, it is critical to consider interactional effects between the two.

Neurobiology

Neurobiological research has begun to elucidate specific brain and neurohormonal features that underpin the phenomenological characteristics of BPD. Neuroimaging studies of BPD have primarily focused on examining the neural basis of the distinct emotional dysregulation characteristic of the disorder. The early wave of these studies documented hyperreactivity in limbic structures, primarily the amygdala (

102,

103), while later studies began to describe distinct dysfunction in prefrontal and frontolimbic activity as the larger mechanism behind emotional dysregulation in BPD (

104–

106). These data support the notion that emotional intensity and dysregulation in BPD is the manifestation of failures of top-down frontal control processes that should modulate the effects of the bottom-up hyperreactive limbic structures. Ruocco and colleagues meta-analyzed the existing neuroimaging literature, concluding that BPD subjects show: 1) activation of a diffuse network of structures in negative emotion processing extending from the amygdala, anterior cingulate cortex, medial and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, superior temporal gyrus, posterior cingulated, and cerebellum; 2) decreased activation of regions extending from the amygdala to the anterior cingulate and dorsolateral prefrontal cortex; and 3) increased activation of greater insula and posterior cingulate cortex (

107).

The specific finding of reduced activation of the anterior cingulate cortex in negative emotional processing distinguishes BPD from MDD (

108), suggesting an important distinction between these disorders. Also, the activity of the insular cortex may underpin a range of symptom sectors in BPD, as this region of the brain has been shown to be involved in the processing of emotional and physical pain, self-awareness, and social cognitive processes involved in empathy and adherence to or violation of social norms. Differences in neural activity in the insular cortex have been demonstrated in the context of difficulties among BPD subjects to sustain and repair cooperation during social exchange (

109). Further research is needed to clarify the overlap of dysfunction in the brain areas implicated in negative emotion processing and interpersonal vulnerabilities in BPD, as these two sectors are most defining of the disorder.

Neuropsychological tests that assess actual brain functioning complement the localization results from imaging studies. They have confirmed dysfunction in such areas as prefrontal (primarily) and additionally, in temporal and parietal cortex (

110,

111). Interestingly, brain lesions in these areas do not produce BPD symptoms (

112), suggesting that brain abnormalities in BPD patients are more related to abnormal function of these areas.

While neuroimagining research has focused on mechanisms of abnormal emotion processing, research on neuropeptides has shed some light on the stress and interpersonal sensitivity of BPD. As discussed above, individuals with BPD commonly experience more early and adult life stress, which may both interact with and be potentiated by genetic factors, in the context of unstable and insecure attachments. As noted earlier (see “Natural History” and “Treatment and Outcome” subsections) many features of BPD are stress reactive. Biologically, elevated cortisol responses to psychosocial stress and dysregulated feedback responses in BPD subjects suggest overall impaired physiological management of stress (

113). Neuropeptide systems involving opioids and oxytocin also effect stress responses show altered functioning in BPD (see

Table 5). Both opioids and oxytocin also facilitate prosocial tendencies. Oxytocin administration is associated with enhanced performance on “mind-reading” or interpreting mental states from social cues (

115) and collaboration in social exchange tasks in normal subjects (

116). Strikingly, the administration of oxytocin to subjects with BPD actually increased mistrust and decreased cooperation in a social exchange paradigm (

116). This suggests that the BPD’s oxytocin system may produce a paradoxical tendency toward mistrust and interpersonal instability in social activity rather than the kind of affiliation that normal oxytocin responses cause.