The natural course of borderline personality disorder and its long-term outcome following treatment are uncertain (

1). A number of well-characterized treatments for borderline personality disorder have been found in randomized, controlled trials to reduce suicidal acts, self-harm, impulsive behaviors, general psychopathology, and service use while improving affective control (

2–

7). More limited evidence exists from these trials for changes in depression, loneliness/emptiness, anger, and social and interpersonal function with little confirmation of sustained improvement in any of these domains. Follow-up after treatment was either absent or too short to assess final outcomes.

Naturalistic follow-along investigations report symptomatic improvement, particularly of impulsive symptoms, over a relatively short period of time but suggest that deficits in interpersonal and social function and vocational achievement (

8) remain over the longer term (

9,

10). But it is difficult to draw firm conclusions about either the natural or treated course of the disorder in the absence of an experimental design with well-defined interventions.

In the short term, controlled studies have found limited between-groups differences at 2 years after entrance into treatment (

6,

11,

12), implying that some treatments may achieve a more rapid natural remission. Longer-term follow-up studies suggesting that posttreatment differences are maintained have lacked adequate comparison groups (

13,

14).

We reported 18-month (end of intensive treatment) and 36-month outcomes of patients treated for borderline personality disorder after random assignment to mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization or treatment as usual (

15,

16). Mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization and treatment as usual for 18 months were well-characterized. Subsequent treatment was monitored. However, the mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization group continued to receive some outpatient group mentalizing treatment between 18 and 36 months. No treatment as usual patients received the experimental treatment during this 36-month period. Differences between groups found at the end of intensive treatment not only were maintained during 18–36 months but increased substantially. We attributed this to the rehabilitative processes stimulated by the initial mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization. But equally it might have been a result of the maintenance outpatient group mentalizing treatment even though this group had considerably less treatment than the control group.

All mentalization-based treatment ended 36 months after entry into the study. We wanted to determine whether treatment gains were maintained over the subsequent 5 years, i.e., 8 years after random assignment. The primary outcome measure for this long-term follow-up study was the number of suicide attempts. But in light of the limited improvement related to social adjustment in follow-along studies, we were concerned with establishing whether the social and interpersonal improvements found at the end of 36 months had been maintained and whether additional gains in the area of vocational achievement had been made in either group. We also looked at continuing use of medical and psychiatric services, including emergency room visits, length of hospitalization, outpatient psychiatric care, community support, use of medication and psychological therapies, and overall symptom status. This article reports on these long-term outcomes for patients who participated in the original trial.

Method

The characteristics of the subjects, the methodology of the original trial, and the details of treatment have been described (

15,

17). Both groups had access to inpatient treatment for acute crises if recommended by the primary psychiatrist. At the end of 18 months, the mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization patients were offered twice-weekly outpatient mentalizing group psychotherapy for a further 18 months, whereas the treatment as usual group continued with general psychiatric care with psychotherapy but not mentalization-based treatment if recommended by the consultant psychiatrist.

Mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization consists of 18-month individual and group psychotherapy in a partial hospital setting offered within a structured and integrated program provided by a supervised team. Expressive therapy using art and writing groups is included. Crises are managed within the team; medication is prescribed according to protocol by a psychiatrist working in the therapy program. The understanding of behavior in terms of underlying mental states forms a common thread running across all aspects of treatment. The focus of therapy is on the patient’s moment-to-moment state of mind. The patient and therapist collaboratively try to generate alternative perspectives to the patient’s subjective experience of himself or herself and others by moving from validating and supportive interventions to exploring the therapy relationship itself as it suggests alternative understanding. This psychodynamic therapy is manualized (

17) and in many respects overlaps with transference-focused psychotherapy (

18).

Treatment as usual consists of general psychiatric outpatient care with medication prescribed by the consultant psychiatrist, community support from mental health nurses, and periods of partial hospital and inpatient treatment as necessary but no specialist psychotherapy.

We initially reported conservatively on all patients randomly assigned to the mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization/group therapy condition regardless of their duration of treatment at 36 months, including dropouts (

16). In the current study, we followed up all 41 patients 8 years after random assignment (5 years after they had ceased all mentalization-based treatment). Contact was made by letter, through their general practitioner, and by telephone. Written informed consent was obtained in person or by letter after the follow-up study had been fully explained according to the requirements of the local research ethics committee. Medical and psychiatric records were obtained for all 41 patients and relevant information extracted. The health service in the United Kingdom requires patients to have treatment in their local area. Tertiary care medical records enable tracing and estimation of health care use over long periods.

The patients in the study group were interviewed by research psychologists who remained blind to original group allocation. One patient in the treatment as usual group had committed suicide. Five patients (three in treatment as usual and two in mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization) refused a personal interview, citing schedule or travel problems. The two mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization patients accepted a telephone interview.

Assessment

The primary outcome measure was the number of suicide attempts over the whole of the 5-year postdischarge follow-up period. Associated outcomes were service use, including emergency room visits; the length and frequency of hospitalization; continuing outpatient psychiatric care; and use of medication, psychological therapies, and community support.

Secondary outcomes were 1) symptom status as assessed at a follow-up interview using the Zanarini Rating Scale for DSM-IV borderline personality disorder (

19) and 2) global functioning as measured by the Global Assessment of Functioning Scale (GAF), which has been found to show less improvement in naturalistic follow-along studies than diagnostic symptom profiles (

20).

At 6-month intervals after 18 months of mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization, we assessed treatment profiles (emergency room visits, hospitalization, psychiatric outpatients, community support, psychotherapy, medication) and suicidality and self-harm using criteria defined in the original trial for each patient by interview and scrutiny of medical records. We also collected information twice yearly concerning vocational status, calculating the number of 6-month periods in which the patient was employed or attended an educational program for more than 3 months. Patient recall for self-harm was unreliable and could not be independently corroborated from medical records and so is not reported. However, we consider the frequency of emergency room visits to be a reasonable proxy of severe self-harm in this population.

The reliability of information gained from medical records was assessed on a random subset of notes (45%), which were independently coded by two researchers. A similar proportion of recorded interviews was assessed for interrater agreement. Although interviews could be conducted blind, data extraction from the medical notes could not be performed without knowledge of treatment allocation. To reduce bias, all pertinent data (e.g., suicide attempts, hospitalization, emergency room visits, vocation) were cross-checked with other sources of information (e.g., emergency room, general practitioner, education institution records). Intercoder agreement was in excess of 90% for almost all variables used (median kappa=0.90, range=0.77–1.00, for each 6-month period). Final GAF scores were assigned independently by two blinded judges on the basis of current case notes and interview information; interrater reliability was 0.72. Aggregate scores were used in the analysis.

The primary outcome measure of suicide had an extremely skewed distribution, and so nonparametric Mann-Whitney statistics were applied to frequency data. We used the Mann-Whitney test or analysis of variance depending on the distribution for the other variables. Multivariate analysis of variance was used to contrast the two groups on the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder. For service use (outpatient psychiatry, community support, and psychotherapy), we computed the percentage of available services used for each patient for the year before random assignment and during subsequent blocks of time (mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization, 18 months), mentalization-based treatment by group (18 months), and postdischarge (0–18 months, 19–36 months, 37–60 months). For the same periods, we also computed the proportion of each group who were hospitalized, made suicide attempts, were employed or in education, attended the emergency room, and were taking three or more classes of medication. For each time block, the proportions were contrasted using chi-square statistics.

Results

Means and standard deviations of primary and secondary outcomes for mentalization-based treatment and treatment as usual groups are shown in

Table 1 covering the 5-year postdischarge period together with significant statistics and effect sizes contrasting the two groups. For frequency, data effect sizes are stated as numbers needed to treat (Newcombe-Wilson 95% confidence interval [CI]).

Overall, 46% of the patients made at least one suicide attempt (one successfully), but only 23% did so in the mentalization-based treatment group, contrasted with 74% of the treatment as usual group. There was a significant difference on the Mann-Whitney U test in the total number of suicide attempts over the follow-up period.

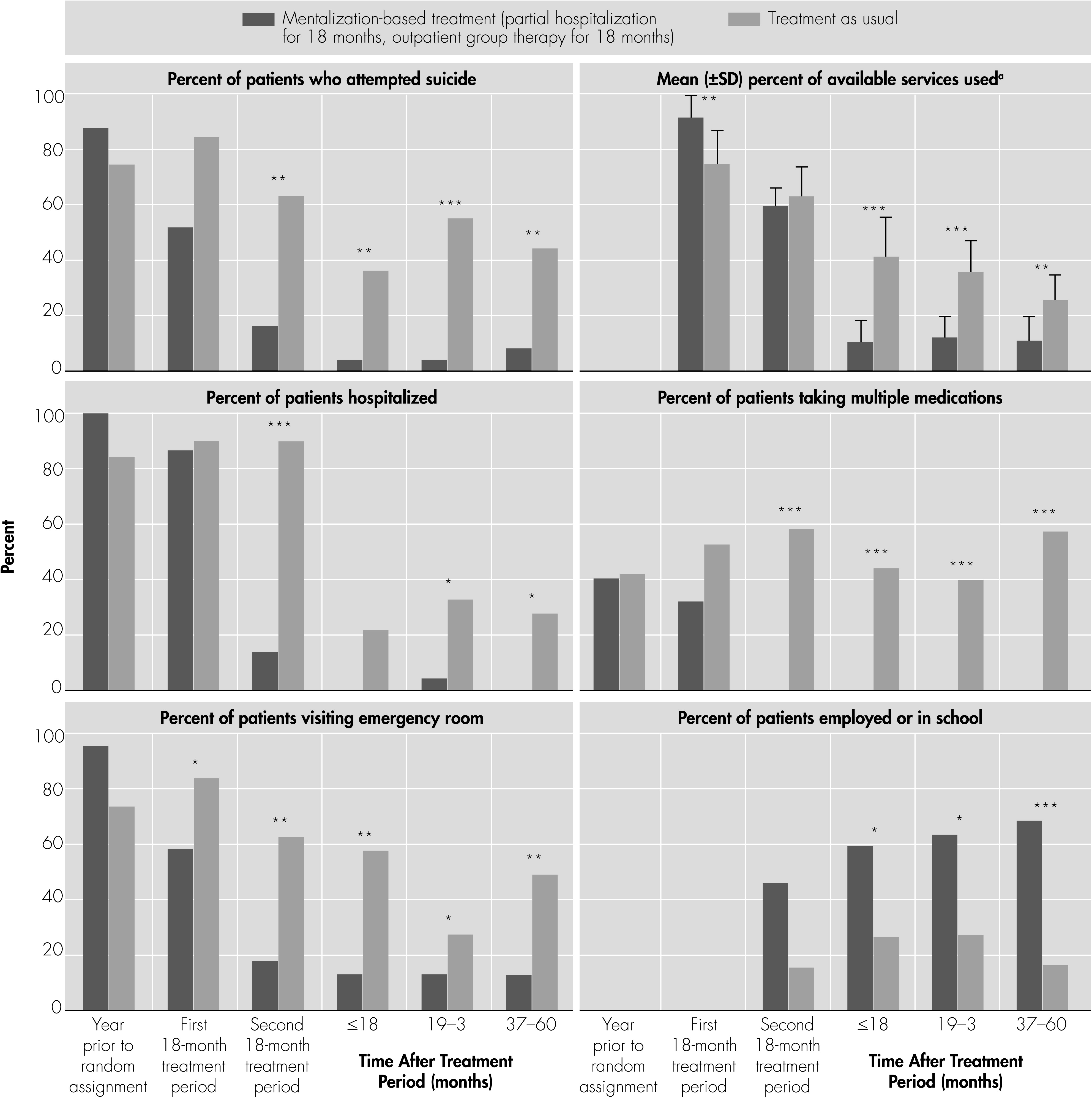

Figure 1 shows the percentage of each group that made a suicide attempt during each block of time. Significant differences between the groups were apparent during the mentalization-based treatment group therapy period and remained significant in all three postdischarge periods.

Table 1 shows that the mean number of emergency room visits and hospital days highly significantly favored the mentalization-based treatment group, as did the continuing treatment profile.

Figure 1 shows the percentage of patients in each group who made an emergency room visit and were hospitalized at least once during the study periods. Emergency room visits were significantly reduced in all periods of treatment and postdischarge. The percent hospitalized was significantly lower during the last two postdischarge periods.

During mentalization-based treatment group therapy, all of the experimental group but only 31% of the treatment as usual group received therapy (χ

2=21, df=1, p=0.0000005). Over the 5-year postdischarge period, both groups received around 6 months of psychological therapy (n.s.). For all other treatments, the treatment as usual group received significantly more input postdischarge—3.6 years of psychiatric outpatient treatment and 2.7 years of assertive community support, compared with 2 years and 5 months, respectively, for the mentalization-based treatment group. The mean percent of available services used throughout the period of the study is shown in

Figure 1. The differences favored the treatment as usual group only in the initial treatment period (mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization) and were significantly less for the mentalization-based treatment group for all three postdischarge periods.

Differences were also marked in terms of medication (

Table 1). The treatment as usual group had an average of over 3 years taking antipsychotic medication, whereas the mentalization-based treatment group had less than 2 months. Somewhat smaller but still substantial differences were apparent in antidepressant and mood stabilizer use. The treatment as usual group spent nearly 2 years taking three or more psychoactive medications, compared to an average of 2 months for the mentalization-based treatment group.

Figure 1 shows that around 50% of the treatment as usual patients but none of the mentalization-based treatment group were taking three or more classes of psychoactive medication during mentalization-based treatment group therapy and the three post discharge periods. At the end of the follow-up period, 13% of the mentalization-based treatment patients met diagnostic criteria for borderline personality disorder, compared with 87% of the treatment as usual group (

Table 1). The contrast between mean total scores for the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder yielded a large effect size favoring the mentalization-based treatment group, albeit with a wide confidence interval. Multivariate analysis of variance across the four symptom clusters also reflected the better outcome for the mentalization-based treatment group (Wilks’s lambda=0.55, F=6.4, df=4, 32, p=0.001). The largest differences favoring mentalization-based treatment were in terms of impulsivity and interpersonal functioning.

Table 1 shows there was over a 6-point difference in the GAF scores between the two groups, yielding a clinically significant moderate effect size of 0.8 (95% CI=–1.9 to 3.4). Forty-six percent of the mentalization-based treatment group compared to 11% of the treatment as usual group had GAF scores above 60. Of importance, vocational status favored the mentalization-based treatment group, who were employed for nearly three times as long as the treatment as usual group.

Figure 1 shows a gradual increase in the percent of mentalization-based treatment patients in employment or education in the three postdischarge periods.

Discussion

The mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization/group therapy group continued to do well 5 years after all mentalization-based treatment had ceased. The beneficial effect found at the end of mentalization-based treatment group therapy for borderline personality disorder is maintained for a long period, with differences found in suicide attempts, service use, global function, and Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder scores at 5 years postdischarge. It is consistent with the possible rehabilitative effects that we observed during the mentalization-based treatment group therapy period. This is encouraging because positive effects of treatment normally tend to diminish over time. The treatment as usual group received more treatment over time than the mentalization-based treatment group, perhaps because they continued to have more symptoms. However, in both groups, GAF scores continue to indicate deficits, with some patients continuing to show moderate difficulties in social and occupational functioning. Nevertheless, when compared to the treatment as usual group, mentalization-based treatment by partial hospital/group therapy patients were more likely to be functioning reasonably well with some meaningful relationships as defined by a score higher than 60.

More striking than how well the mentalization-based treatment group did was how badly the treatment as usual group managed within services despite significant input. They look little better on many indicators than they did at 36 months after recruitment to the study. A few patients in the mentalization-based treatment group had made at least one suicide attempt during the postdischarge period, but this was almost 10 times more common in the treatment as usual group. Associated with this were more emergency room visits and greater use of polypharmacy. However, although the number of hospital days was greater for the treatment as usual group than the mentalization-based treatment group, the percentage of patients admitted to the hospital over the postdischarge period was small (25%–33%). This pattern of results suggests not that treatment as usual is necessarily ineffective in its components but that the package or organization is not facilitating possible natural recovery.

Naturalistic follow-up studies suggest spontaneous remission of impulsive symptoms within 2–4 years with apparently less treatment (

21,

22). In line with these findings, all patients showed improvement, although not as much in terms of suicide attempts as might be expected. The lower level of improvement observed in this population may represent a more chronically ill group. Most patients had a median time in specialist services at entry to the trial of 6 years. Although this study does not indicate the untreated course of the disorder, the results suggest that quantity of treatment may not be a good indicator of improvement and may even prevent patients from taking advantage of felicitous social and interpersonal events (

23). It is possible that treatment as usual inadvertently interfered with patient improvement as well as mentalization-based treatment accelerating recovery.

There is an anomaly in the results in that there is a marked difference between the size of the effects as measured by the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder and the GAF in terms of social and interpersonal function. One possible explanation for this is that the scales offer a slightly different metric to different aspects of interpersonal function. In the GAF, suicidal preoccupation and actual attempts have a large loading, and even presence of suicidal thoughts reduces the score substantially. This was the case for a small number of patients in the mentalization-based treatment group and accounts for their larger variance on GAF scores. In contrast, the interpersonal subscale of the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder covers two symptoms in the interpersonal realm of borderline personality disorder, namely, intense unstable relationships and frantic efforts to avoid abandonment, that showed marked improvement in the mentalization-based treatment group. A GAF of greater than 60 clearly marks a change back to improved function, and more patients in the mentalization-based treatment group achieved scores above this level. A strong correlate of improvement in the mentalization-based treatment group is vocational status. It is unclear whether this is a cause or consequence of improvement. It is likely that symptomatic improvement and vocational activity represent a virtuous cycle. Although we have no evidence to this effect, we suggest that mentalization-based treatment may be specifically helpful in improving patient ability to manage social situations by enabling individuals to distance themselves from the interpersonal pressures of the work situation, anticipate other people’s thoughts and feelings, and be able to understand their own reactions without overactivation of their attachment systems (

24,

25).

The strengths of this study lie in the presence of a long-term control group, in the reliability of care records, and in our data collection for suicide attempts, which used the same rigorous criteria as at the outset of the trial. Other follow-up studies have been confounded by a lack of controls or treatment as usual patients being taken in to the experimental treatment at the end of the treatment phase. However, the long-term follow-up of a small group and allegiance effects, despite attempts being made to blind the data collection, limit the conclusions. In addition, some of the measures we used at the outset of the trial were not repeated in this follow-up. We considered the Zanarini Rating Scale for Borderline Personality Disorder to be a more useful outcome measure that would reflect the current state of the patients better than self-report questionnaire methods. Finally, the original mentalization-based treatment by partial hospitalization intervention contained a number of components in addition to psychological therapy. It is therefore unclear whether psychodynamic therapy was the essential component. In order for mentalization-based treatment to be accepted as an evidence-based treatment for borderline personality disorder, larger trials using core components of the intervention are necessary. These are now being undertaken. Although this study demonstrates that borderline patients improve in a number of domains after mentalization-based treatment and that those gains are maintained over time, global function remains somewhat impaired. This may reflect too great a focus during treatment on symptomatic problems at the expense of concentration on improving general social adaptation.