Case Vignette Part 1: Presentation to Clinic for Returning Veterans

David is a 32-year-old married Caucasian male seeking psychiatric help following the loss of his job and stressors in his marriage. He was referred to VA mental health services by an employment counselor who identified him as a veteran of the wars in Afghanistan (Operation Enduring Freedom) and Iraq (Operation Iraqi Freedom) and who felt he needed additional assistance beyond employment counseling.

Upon arrival at the clinic for returning veterans, David expressed an interest in curbing his temper, and he attributed his marital and work-related problems to outbursts at home and on the job. He admitted to feeling depressed and unable to organize himself at work or at home. An engineer by training, David enlisted in the Army following completion of his degree in electrical engineering. An honors graduate of a prestigious university, David trained in the safe detonation of explosive devices and was assigned to an explosive ordinance division. He served three separate tours, one in Iraq and two in Afghanistan. In total, he was deployed to a warzone for nearly 3 years. He was discharged honorably from the Army in 2010 and returned to a small city in New England to begin his postmilitary life.

Upon presentation in the clinic, David spoke with pressured speech while describing his background and family history. His upbringing was largely unremarkable in that he was raised in a middle-class family by both parents whom he described as caring and conscientious people who afforded their three children a stable home in a good community with many educational opportunities. His decision to join the military was a function of deep-rooted patriotism in his family and a history of military service among the men. He was inspired to help the United States end terrorism following the attacks of 9/11.

David married his college girlfriend upon completion of his military training. She was supportive of his service, but reported considerable anxiety at the point of each of his deployments. Upon his return from a second deployment, she wanted him to return to civilian life. It was soon after this tour that his wife became pregnant and delivered a healthy daughter. At the time he sought help, his daughter was 3 years old.

Consideration Point A

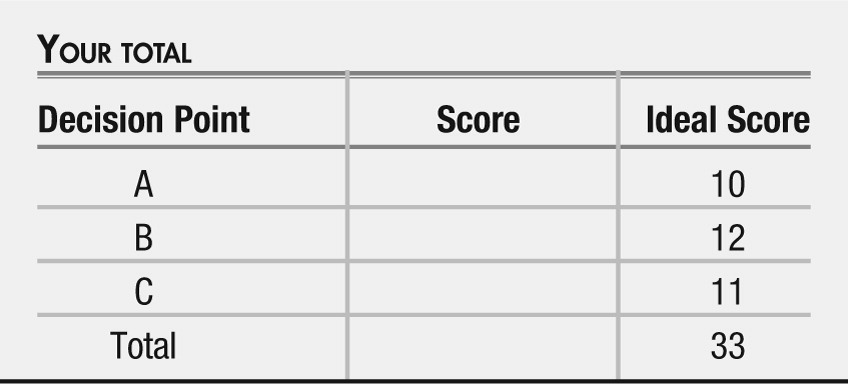

At this point in the evaluation, the diagnoses that seem most appropriate for this patient would be:

| A.1_____ | Major depressive disorder |

| A.2_____ | Posttraumatic stress disorder |

| A.3_____ | Alcohol abuse |

| A.4_____ | Bipolar disorder |

| A.5_____ | ADHD |

Case Vignette Part 2: Comprehensive Psychiatric Assessment and Gathering Further History

A comprehensive psychiatric assessment included a history of his military experiences, assignments, tours of duty, and a mental status exam. Also included in this assessment were: 1) the Deployment Risk and Resilience Inventory (DRRI) (

1); 2) the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

2); 3) the Clinician-Administered PTSD Scale (

3); and 4) psychological tests including the PTSD Checklist (PCL) (

4), the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI) (

5), the Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) (

6), and the Spielberger Anger Inventory (STAXI) (

7). This approach to assessment was supplemented by specific questions regarding suicidal ideation and exposure to blasts while in training and in the warzone with a particular focus upon assessing mild traumatic brain injury (mTBI). His wife was also interviewed by herself in order to obtain additional information about their relationship and his functioning.

Results of the evaluation suggested that David possessed a loving and supportive family; his parents and wife were deeply concerned about his postdeployment functioning and were prepared to provide any necessary resources in order to foster optimal adaptation. Examining his combat exposure and related stressor exposures, it was clear that David experienced considerable stress during each of his three tours of duty, the most difficult of which was his third tour during the period of quelling the Sunni insurgency in Iraq. He described this period as filled with a barrage of firefights coupled with many, many initiatives to detonate improvised explosive devices (IEDs). Reports of IED attacks on American troops added to the anxiety that he and others in his division experienced. His predominant mode of coping was to shut down emotionally. This conscious effort to stem his own anxiety led to a sense of emotional numbing that continued to the present.

Consideration Point B

The methods employed to evaluate this patient included the following approaches:

| B.1_____ | Structured diagnostic interviews |

| B.2_____ | Psychological tests and questionnaires |

| B.3_____ | Military history measures |

| B.4_____ | Mental status examination |

| B.5_____ | Amytal interview |

Vignette Continues: Findings of the Evaluation

Examination of the results of the structured diagnostic interviews suggested the following: David met diagnostic criteria for PTSD, major depressive disorder (MDD), and alcohol abuse. He also endorsed several symptoms of bipolar disorder, but didn’t meet full diagnostic criteria for this condition. Using the SCID for measuring disorders other than PTSD revealed the presence of risky alcohol use, a problem that wasn’t acknowledged in the psychiatric history. It was only upon specific questioning of the patient about his use of alcohol that a pattern of risky use and abuse emerged. Scores on the BDI and the BAI were clearly elevated and confirmed the concurrent presence of a broad-based anxiety and mood disorder. The PTSD Checklist score of 62 easily exceeded the threshold for PTSD caseness. Suicidal ideation was fleeting, with little information regarding a specific plan. Exposure to many blasts, some at relatively close range (50 yards), led to further exploration of mTBI, but there wasn’t evidence that he’d ever lost consciousness or had other symptoms of postconcussive syndrome.

When the findings of the evaluation were explained to David and his wife, they were surprised. David had experienced very high levels of combat exposure even compared with others who served in these war zones. The periods in which he served were characterized by considerable contact with enemy troops and the use of explosive devices by the enemy. This comparative information surprised David as he felt that he experienced the same as others, no more or less. The issue of risky alcohol use or abuse was also notable in terms of their receipt of this information. David dismissed his drinking as normative for his peer group of returning veterans, while his wife clearly saw the alcohol use as a major problem but one about which she hadn’t yet communicated her feelings to him.

Despite all of the information about PTSD in the media, this couple was surprised by the extent and the severity of this problem for David. In his view, he was minimizing these symptoms as common ones that everyone in a war zone experiences. From her perspective, she knew that he was distant, that he didn’t sleep very well, and that he had nightmares. They actually spoke very little about his time in the war zones and she was surprised at his level of symptomatology. She saw only the ease with which he became angry and his sleeplessness. The more cognitive symptoms of reliving the war, preoccupation with the deaths of his buddies, and his sense of survivor guilt were not at all apparent to her. She noted that he was jittery and startled easily, but felt that these problems would diminish over time.

Treatment options offered to David were all outpatient-based. His highest priority was to improve his sleep and to address the nightmares he experienced several nights each week. He felt that if he could accomplish this, then he would be less angry, depressed, and more likely to be able to work. Options offered to David were the use of a selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor (SSRI), but it was explained that this might take weeks to months to exert its full effects (

8). They agreed to its use. Secondly, we offered him a trial with prazosin, an antihypertensive medication that was observed to reduce the frequency and intensity of nightmares and thereby improve sleep in patients with PTSD (

9,

10). Again, they agreed to a trial of prazosin.

Consideration Point C

For psychological treatments for patients with PTSD, there are several treatment options with substantial evidence bases. In this particular case, which treatment might be optimal given the circumstances:

| C.1_____ | Exposure therapy |

| C.2_____ | Cognitive processing therapy |

| C.3_____ | Behavioral couples therapy for alcohol |

| C.4_____ | Cognitive behavioral conjoint therapy for PTSD |

| C.5_____ | Both 3 and 4 concomitantly |

Vignette Concludes

Next, we offered the available evidence-based cognitive behavioral treatments for PTSD: exposure therapy, cognitive processing therapy (CPT), and couples therapy for PTSD. Exposure therapy has many facets that include patient education about trauma, skills training, and processing of new perspectives on the experiences associated with traumatic events. Prolonged exposure therapy is one form of exposure therapy that is easily the most well studied approach to treating PTSD (

11). Other forms include nightmare rehearsal training, imagery rehearsal, narrative exposure therapy, and written disclosure therapy (

12–

14). All possess a significant evidence base.

CPT is also extensively studied in a variety of PTSD patient types and possesses a strong evidence base (

15,

16). This therapy involves promoting cognitive reappraisals of the traumatic experiences, teaching alternative views, providing a variety of specific behavioral coping strategies, and challenging key cognitive distortions about the individual, the traumatic situation, and the future.

The third option was for couples conjoint therapy for PTSD (

16). This approach involves emotional processing in the context of couples treatment. It promotes the use of the couple as a supporting entity that can mitigate the impact of trauma. There is also considerable education contained within the treatment package. Importantly, the couple is the unit of treatment and this approach implies that it is through a couple’s communication and support that the emotional responses associated with trauma exposure can be managed effectively (

17). Importantly, there is considerable evidence to support the use of behavioral couples therapy to reduce drinking and promote sobriety (

18). Integrating these two approaches to the treatment of PTSD and alcohol abuse was viewed by David and his wife as the clear treatment of choice. The presence of a supportive and loving relationship made this option for psychotherapy a compelling choice for this couple.