Relationships matter—in health, disease, coping with stress, and recovering from illness. This is the rationale for interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) (

1), a time-limited psychotherapeutic model that focuses on relational aspects of experience and mental health. IPT treats depression across the life span (

2–

4), and has been successfully adapted for differing clinical populations, including those with bipolar disorder (

5), posttraumatic stress disorder (

6,

7), and eating disorders (

8,

9). IPT can be effectively delivered by a variety of health providers from mental health specialties such as psychiatrists, psychologists, nurses, social workers, and occupational therapists; to trained lay health workers (

10). This range of treatment providers can help to address the wide global gap between the need for, and access to, mental health care (

11,

12).

The first controlled IPT study for depression was published 40 years ago (

13). Since then, novel applications of the model have emerged, informed by research and public health needs. Evidence for its antidepressant effects, established through numerous clinical trials (

14) has led to its inclusion in expert depression treatment guidelines (

Table 1) (

16,

17,

24) including those of the World Health Organization (WHO) (

18). Consensus guidelines for the treatment of eating disorders and bipolar disorder also recommend IPT, based on level 1 evidence of at least two randomized clinical trials conducted by two separate groups of investigators demonstrating positive outcomes (

20–

22).

At the time of IPT’s genesis, Bowlby’s seminal work on attachment theory (

25,

26), Brown and Harris’ studies on the associations between bereavement and depression (

27), and the etiological links between biological and psychosocial factors were becoming influential in the discourse on illness and recovery (

28,

29). Since that time the importance of relationships for health, coping, and resilience has become well established (

30–

33). Mental illnesses are often triggered or exacerbated by relationship stressors, such as interpersonal losses, life changes, loneliness, or conflicts. IPT treatment provides therapeutic roadmaps to work through these core relationship focus areas.

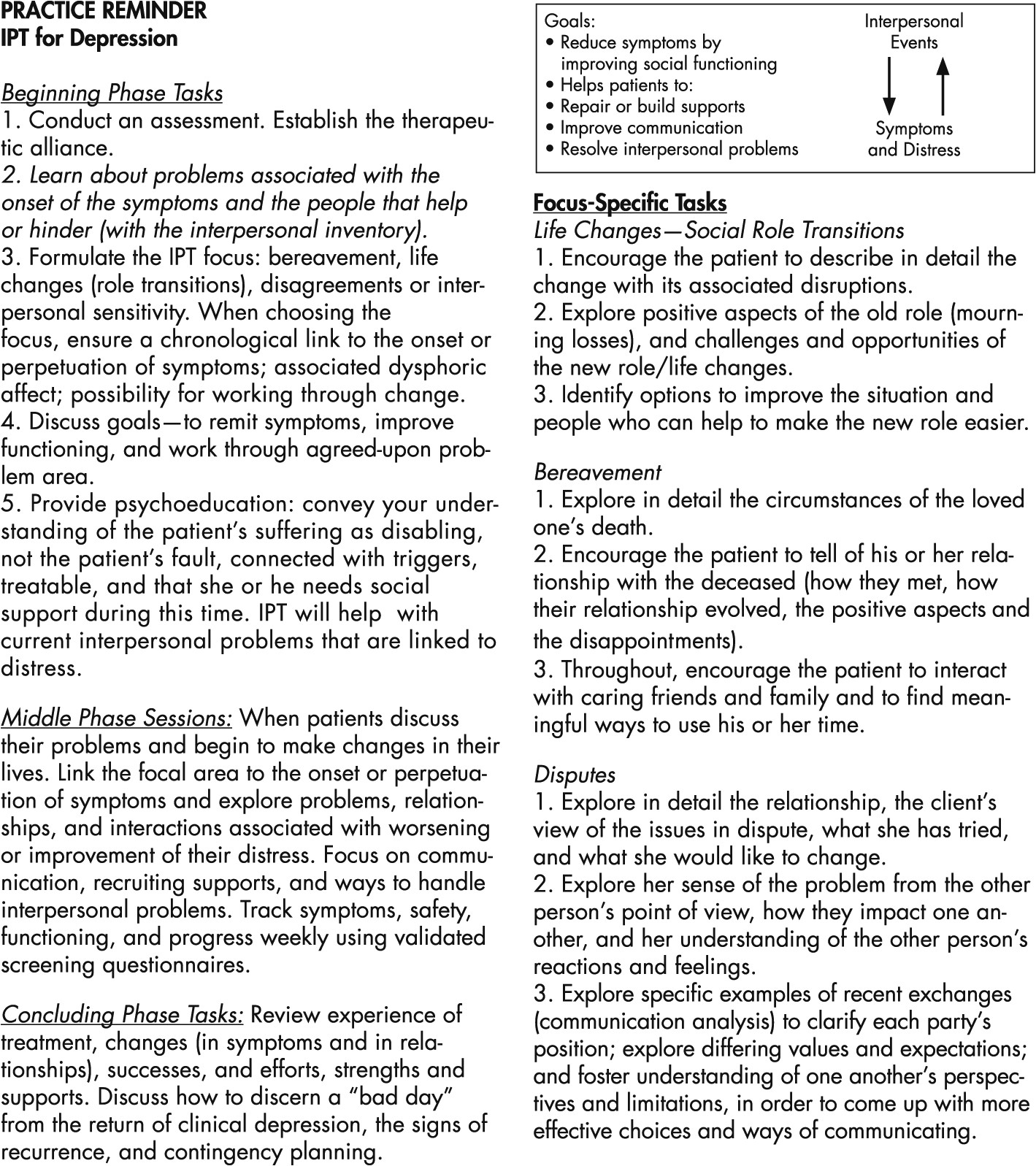

This paper provides an overview of IPT (

1) with an emphasis on the clinical guidelines as summarized in

Figure 1 (

34). It is beyond the scope of this clinical synthesis to describe all IPT adaptions in depth; however, we briefly review those included in consensus treatment guidelines (

Table 1). These include: IPT-A, for use with adolescents with depression; IPSRT, for patients with bipolar disorder; IPT, for patients with eating disorders; and IPT, for patients with depression in culturally diverse settings. We begin by describing and discussing the evidence supporting each adaptation of IPT and then review the components of the original treatment.

IPT-A

Depression poses severe risks to adolescents, including incomplete schooling, substance abuse, early pregnancy, self-harming behaviors, recurrent depressive episodes, and physical morbidity. By age 18, an estimated 20% of adolescents will have had a major depressive episode (

35). An intervention to treat, and potentially prevent the recurrence of depression, is therefore of great public health significance. Mufson and colleagues created and piloted the IPT-A model during the 1990s, when there were no published controlled trials for any individual psychotherapy for depressed adolescents (

36). Since then, IPT-A has been established as an effective treatment in numerous controlled trials (

2,

37,

38). IPT-A adheres to the core tenet that relationships are the locus of intervention and healing, but also contains important developmentally-oriented modifications. These modifications take into account the differences in life circumstances and maturation tasks that confront adolescents (

39). Aligned with the developmental needs necessary for healthy adolescent maturation, areas of therapeutic work in IPT-A include: reducing conflict in relationships, developing and using healthy communication strategies, resolving identity crises, and building and maintaining a supportive set of relationships with the family and peers.

IPT-A remains a brief psychotherapy (12 sessions) with distinct phases and the same focal areas as IPT. It also employs strategies for engaging adolescents, such as telephone contact between sessions. Another important modification of IPT-A is including parents or other primary caregivers in all phases of the therapy process. Parents join the diagnostic assessment and psychoeducation at the beginning, including conveying a “limited sick role” to the adolescent. With the adolescent’s permission, parents may attend some middle phase sessions, to orient them to the new strategies the teen will be trying at home, and where needed, to address disputes within the family. In the termination phase, both the adolescent and parents will join in a review and consolidation of gains, with discussion of early signs of relapse, and development of a plan for possible future depression recurrence.

Vignette 1: an Example of an IPT-A Case With a Focus on Disputes

Greg is a 15-year-old adolescent with a 1-year history of low mood, anergia, anhedonia, and difficulty with concentration and academic performance. He denied suicidal ideation and substance abuse. At the time of his assessment, Greg rarely attended school, which was the subject of near-daily arguments with his mother. He had stopped all extracurricular activities, including soccer and drama, which he used to enjoy. He typically stayed awake for most of the night, often playing computer games online, and slept during the day. His absences from school resulted in failing grades and increasing social isolation from his friends.

Greg was an only child who lived with his mother. When questioned about his life at the time of the onset of his depressive symptoms, he recounted a series of verbal conflicts with his parents who had separated two years ago. Greg cut off contact with his father a year ago, feeling hurt by what he perceived as a lack of support and interest.

In IPT-A, meetings with a parent are held in the beginning phase, and in this case the therapist met Greg and his mother to discuss the diagnosis of depression, instill hope, and provide psychoeducation on depression, IPT, and the impact of depression on Greg’s willingness and ability to succeed at school. They discussed that Greg’s social isolation, frequent conflicts with his mother, and alienation from his father might be driving his depression. The therapist explained that Major Depressive Disorder was a treatable condition and that Greg would feel and function much better as his depressive symptoms began to remit.

Middle phase sessions focused on the disputes with Greg’s parents and included some joint sessions with his mother; however, he did not wish his father to come in. Greg and his mother collaboratively devised communication strategies for their arguments. After a number of sessions exploring wishes and expectations, doing role plays and problem-solving, Greg’s relationships with both parents improved, and he restored contact with his father. Over time, Greg contacted friends and began to re-engage in his social life. By 8 weeks of IPT-A, his depressive symptoms remitted and he was functioning well at home and at school. At the termination of therapy, Greg acknowledged, with relief, the significant improvements in his mood and close relationships, and his therapist emphasized that Greg now had a set of communication tools and relationship strategies that he could use whenever he experienced low mood.

Interpersonal Social Rhythm Therapy (ipsrt)

Bipolar disorder is a chronic psychiatric illness characterized by alternating depressive and [hypo]manic mood episodes that can cause serious negative consequences to the patient and his or her family if left untreated. Rates of conversion from unipolar to bipolar disorder are relatively low. However, bipolar disorder is commonly misdiagnosed as unipolar depression; and treatment-refractory depression may, in some cases, represent occult bipolar disorder, with its attendant greater severity and functional impairment. Although bipolar disorder is much less prevalent than major depressive disorder, it is challenging to treat and often impacts upon the life circumstances and relationships of patients and their families in debilitating ways such that bridges are burned, and social development is derailed (

5). Frank, Swartz, and colleagues created IPSRT for this patient population, based on the findings that radical changes in daily routines precede circadian rhythm instability, which can lead to affective episodes (

40,

41). IPSRT utilizes the Social Rhythm Metric (SRM), a behavioral tool (

42) developed to help stabilize circadian and social rhythms during manic or depressive phases of bipolar illness and to provide patients with skills that will help prevent the onset of future episodes (

43,

44). The SRM tracks five distinct activities: the times they get out of bed; have first contact with another person; start meaningful activity such as work, school, housework or volunteering; have dinner; and go to bed. Patients also record whether they were alone or with others when they participated in each daily activity. Finally, patients rate their mood and energy level each day. Therapists use the SRM to identify links between fluctuations in mood and regularity of routines. Over time, unstable social rhythms that negatively impact mood or energy are identified as targets for change, moving toward a balance of rest, activity, and personal contacts that promote mood stability.

Frank et al. suggest combining mood stabilizing medication, IPT, and the simple SRM behavioral tool to restore circadian and social rhythms during the acute and maintenance phases of treatment, helping to stabilize symptoms and decrease the risk of relapse (

45). Compared with intensive clinical management, patients with bipolar disorder treated with IPSRT have reduced rates of relapse and higher regularity of social rhythms at the end of acute treatment. Additionally, IPSRT is shown to be effective in reducing suicidal behavior in patients with bipolar disorder (

46). As IPSRT has been shown to delay relapse, speed recovery, and increase both occupational and psychosocial functioning (

43), it has been recommended in consensus treatment guidelines for bipolar disorder (

21).

IPT for Eating Disorders

Eating disorders such as bulimia nervosa, anorexia nervosa, and binge-eating disorder represent a public health concern due to their increasing prevalence (

47) and association with elevated mortality rates (

48). IPT has been studied with patients who have these eating disorders, with the target of treatment being the interpersonal difficulties that maintain symptoms (

8,

9,

49). Randomized controlled trials have indicated that, for patients with bulimia nervosa or binge-eating disorder, IPT takes longer than Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT) to achieve recovery; however, both models of treatment are equally effective.

Both models, despite having differing emphases—for CBT to modify distorted thinking about shape and weight, and for IPT to modify interpersonal functioning—have been shown to effect changes in both cognitions and relationships (

49). Long-term recovery rates for patients with anorexia nervosa hover around 49%, whether treated with CBT or IPT, which suggests that supplementary or longer treatment approaches may be needed for anorexia nervosa (

50).

IPT in International and Trans-Cultural Settings

Underdetected and untreated mental illness has been identified by the World Health Organization as a severe global problem (

51), for which many global mental health initiatives are now underway. IPT has been at the forefront of efforts to increase access to culturally appropriate psychotherapy for common mental disorders. Adaptations of the IPT model with far-reaching public health scope have been developed for a number of international and transcultural settings. Over the past decade, IPT has undergone significant cultural and methodological reworking, for implementation in settings such as Uganda, Rwanda, India, and Ethiopia (

52–

58) and for use among specific cultural populations in North America (

59,

60). These studies addressed the intersection of culture, illness, and healing. Significant changes were made to diagnostic instruments in these studies, with piloting and cultural validation of the language and concepts used (

61,

62). Local health-care workers were trained to deliver IPT, increasing the capacity for ongoing local service provision once the studies were complete. Treatment groups were chosen to reflect the local reality and public health needs, rather than “pure” depression cases; such as the work done with internally displaced youth in northern Uganda, who presented with ongoing severe psychosocial stressors and numerous psychiatric comorbidities (

53).

These international IPT studies have contributed to the advancement of global psychotherapy research through their innovative methods. The Uganda IPT trials, for instance, began by developing mechanisms for the cross-cultural adaptation and validation of assessment instruments. This ensured that the diagnostic category of depression, which varies in meaning across cultures and social contexts, was a valid measurement category (

54). These studies were also groundbreaking as they were the first published controlled clinical trials of psychological interventions in sub-Saharan Africa, and they provided an early evidence base for the feasibility of future psychotherapeutic interventions in this region (

54,

58). Given the 2004 WHO findings that 76−85% of the individuals with serious mental illness who lived in less-developed countries received no treatment in the preceding year, studies that demonstrate the validity and feasibility of an effective treatment provide an essential public health service. These studies provide a rationale for resource allocation and systemic effort for treatment of these disorders. This is particularly important in resource-poor and underserviced countries where the physical and mental health needs are great and the spending constraints are severe.

IPT Formats

IPT can be delivered in differing formats and doses. For group IPT, additional therapeutic processes to capitalize on the dynamic therapeutic elements of group, such as cohesion, universality, group learning, and receiving constructive feedback from other members, are integrated into the treatment (

63). In addition, there are ultra-brief versions of IPT, one which focuses on screening, support, and triage (

64), and another, called Interpersonal Counseling (IPC) that with as few as six sessions, using the same core principles as IPT, has been shown to be helpful in primary care settings (

65). Having outlined the background and several variations of IPT, we will now describe the clinical guidelines that apply regardless of dose (4–16 sessions) or format (individual or group therapy).

IPT Clinical Guidelines

Like all time-limited psychotherapy treatments, IPT has beginning, middle, and termination phase tasks. The IPT guidelines must still be delivered with attention to good therapeutic processes such as using empathy, mentalizing, and reflection with positive regard and respectful engagement to foster a strong therapeutic alliance.

Beginning Phase of IPT

The beginning phase, akin to all psychiatric and psychotherapeutic treatments, entails getting to know your patient, establishing a therapeutic alliance, and clarifying the goals that will guide the treatment. A psychiatric assessment is done to learn about the individual patient, his or her suffering, symptoms, and important close relationships. We suggest adding cultural formulation questions (

66) to learn about the meaning of symptoms or illness, current practices of coping, and expectations for care. Explicitly inquiring about the cultural aspects of the presentation will serve to increase the therapist’s understanding of the patient, reduce misrecognition of symptoms, and likely improve the therapeutic alliance (

67).

An important goal of the initial phase of IPT is establishing the interpersonal problem area. In IPT’s standard formulation, the therapist chooses among four possible problem areas: 1) grief (difficulty mourning the death of an important person in the patient’s life, 2) role transitions (change in major social roles such as graduation, divorce, retirement, and job promotion), 3) role disputes (nonreciprocal role expectations between the patient and a significant other), or 4) interpersonal sensitivities (long-standing impoverished or contentious relationships).

If symptoms and functional impairment are high or chronic, then adjunctive antidepressant pharmacotherapy should be considered and discussed with the patient. The beginning phase involves gathering and communicating much information, including delivering psychoeducation about the mental disorder and its treatment, the rationale and description of IPT, and the instillation of hope for recovery.

During the beginning phase, the therapist gathers an expanded psychosocial history called the “Interpersonal Inventory.” The Interpersonal Inventory consists of a careful review of the people in the patient’s current relationships and life circumstances who are close, or with whom there are distressing conflicts. This is done in order to identify those who help or hinder in times of need. In the process of conducting the Interpersonal Inventory, a clinician gains an appreciation of a patient’s significant past and present relationships. Losses, tensions, disagreements, trauma, and patterns of relating are revealed through the Inventory, helping to highlight relationships that may be appropriate for therapeutic focus. For example, a patient might become tearful, or less coherent with a reduced capacity to be clearly descriptive of specific relationships during the Inventory process, signaling possible unresolved trauma. The beginning phase ends when an IPT focus is collaboratively chosen for the middle phase. This requires transparent discussion between the therapist and the patient about which interpersonal focal area and which relationships will comprise the focus of treatment. Getting agreement on the IPT focus sets the stage for doing work on the interpersonal problem area most saliently linked to the current illness episode. Although a relatively discrete and specific interpersonal issue is chosen as the focus of IPT treatment (see below), the IPT problem area is often the proverbial tip of the iceberg. The problem area may be indicative of more pervasive interpersonal difficulties such as chronic relationship disputes or maladaptive patterns of coping with stress. The time-limited intervention of IPT does not profess to bring about significant character change; however, the discoveries and changes made over the course of therapy, although brief, can be generalized beyond current circumstances.

In the middle phase, the IPT therapist facilitates reflection, making links between distress or symptoms, relational experiences, and the interpersonal problem area. The early middle phase involves fostering a deepened understanding of current relationships, interpersonal problems, and experiences; whereas in the latter middle phase there is a push for change as patients generate ideas for problem solving, interpersonal activation, and engagement with supports.

Middle-Phase Focus Specific Therapeutic Guidelines

Grief

In the case of bereavement, during the early middle phase, the details of the death, burial, and acute period of grieving are reviewed. The guidelines provided by Klerman, Weissman, and Markowitz provide a powerfully helpful therapeutic roadmap for therapists to guide patients through the process of working through emotionally painful losses (

1). The therapist guides the patient to reflect on the lost significant other and this relationship, returning with greater depth of exploration than when first described during the Interpersonal Inventory. For relationships in which there were ambivalent feelings and conflict, it is important to pace the exploration slowly, so that there can be emotional processing to integrate traumatic aspects of the loss. In the latter middle phase of working with grief, ways to “move on,” and to replace aspects of what has been lost from this relationship through other social supports are discussed.

Role Transitions

The notion of social roles provides a helpful conceptual idea for the multiplicity of expectations in relationships that are held in differing contexts and with differing levels of intimacy. These include relationships within families, romantic connections at work or school, and in community or religious groupings. Social roles define expectations in relationships, and inevitably change over time. Life changes, with their accompanying social role changes, are called “role transitions” in IPT. Role transitions are situated both externally and internally—in their impacts upon relationships, and the patient’s sense of self. Transitions can be planned or unplanned, wished for or dreaded. Examples of role transitions include: becoming a new parent; marrying or divorcing; migrating; becoming medically or mentally ill; and changes in vocational status such as becoming promoted, unemployed, or retired. Role transitions, with their demands and stresses, can precipitate or worsen states of mental illness such as depression. IPT techniques for addressing role transitions include exploring the change with its losses, challenges, and opportunities. For instance, there may be positive aspects of an “old role” that could be carried forward in some way. Opportunities presented by the new role include changes in appreciation, perspective, relationships, and behaviors to better align with a patient’s values, sense of well-being, and meaningful engagement.

Vignette 2

The next example is of an IPT case with a focus on role transitions. Patricia is a 37-year-old married mother of a healthy 4-week-old baby boy. She was referred by her family physician for IPT treatment of postpartum depression. This was a planned pregnancy and there were no complications. Patricia worked as an accountant but was currently on maternity leave. Although she had been excited to become a new mother, she was surprised to find herself tearful and sad most days, with a diminished sense of self-esteem. Though she was highly accomplished as an accountant, she had trouble breastfeeding and felt incompetent, out of control, and overwhelmed as a new mother. She also felt guilty that she experienced little pleasure or connection with her newborn son. She was not suicidal and had no thoughts of harm to her child.

The Interpersonal Inventory, conducted in session 2 after the assessment, revealed that she felt estranged from her spouse and, unaccustomed to asking for help from others, felt quite isolated. Prior to becoming a mother, both she and her husband worked very long hours and socialized mainly with their single friends who were not parents.

In keeping with the middle phase tasks of IPT for role transitions, the therapist explored how Patricia’s life had changed, her sense of having lost the positive aspects of her life before the birth, when she had more flexibility and a lessened sense of responsibility at home. She also voiced confusion about managing her new social role, feeling overloaded with responsibilities and the need to master child care, breastfeeding, and emotionally connecting with her baby. Patricia worked on giving herself permission to gradually learn the many new skills she needed, including breastfeeding, and to recruit support from her extended family, who were happy to help. Over the latter middle phase, as her depression remitted, she became more comfortable asking for help from others, especially her spouse. She came to embrace and enjoy the opportunities of her new role and of her relationships with her spouse and their son.

Role Disputes

There is a sequence of therapeutic tasks in the focal area of disputes. The first of these is to engage, through detailed exploration, with the relationship with the disputed other. The core issues in the dispute, such as transgressions of trust, disparate values, or nonshared expectations, are identified, with a focus on promoting reciprocal understanding. This goes hand-in-hand with improving communication via unpacking upsetting interactions (see Communication Analysis below) and behavioral experiments of interacting from a place of better understanding. Interpersonal expectations are explored and sometimes adjusted toward what is both reasonable and realistic, considering the capacity and perspectives of the other. By working on a current dispute, problematic patterns of relating in which a patient inadvertently “fuels the fire” of the conflict, or creates interpersonal distance, can be helpfully addressed and may often be generalized to improve relationships more broadly.

Interpersonal Sensitivity, also known as

deficits in earlier descriptions of IPT, is a problem area that is sometimes left out of adaptations of the manual. Considered a default category by some, this focus is chosen when there is an absence of life events or close relationships. In cultural adaptations of IPT used in low and middle income countries with communal societies, deficits in social supports are not usually a focus of treatment; however, recruiting of social supports is a pan-focal task used with all IPT patients. In process research, this focal area has not been implicated as having worse outcomes (

68).

For the focal area of interpersonal sensitivity, rather than striving for full “resolution” of the problem area, the goal is to “lessen” it. An IPT strategy for interpersonal deficits is to review negative and positive aspects of past significant relationships (e.g., friendships, romantic relationships, and even past therapeutic relationships). This can reveal patterns of relating that are interpersonally distancing, and that may be recapitulated in the current therapeutic relationship. Unlike other IPT focal areas, the therapeutic relationship can be psychodynamically explored in conjunction with an active focus on expanding social supports.

Vignette 3

A 41-year-old male consultant who presented with chronic depression that had recently worsened in the context of being rejected by an online dating site described having no close relationships. During sessions, he was averse to expressing or identifying emotions and was quite sophisticated in drawing the therapist into intellectual themes. He spoke with frustration of his past experience of psychotherapy in which he felt unhelped, and said that his therapist “didn’t get to how I felt.” This statement provided leverage to collaboratively explore his emotional experience of the current therapy session. The patient identified his use of his intellect to engage with people, yet found the friendships distant and unsatisfactory. In becoming more expressive of his inner, emotional experience of relationships in the here-and-now of the session, the patient felt understood and helped. Roles plays, communication analyses, and brainstorming were used to help improve his interactions with others. Over the remaining course of IPT sessions, his depressive symptoms lessened, he became more in touch with his own emotions, and as well, he became involved in a community-based project, volunteering his skills in a hobby he enjoyed that decreased his social isolation.

In the case of social deficits, as illustrated in the case above, brainstorming with the patient on ways to reduce social isolation and engage with others who share the patient’s interests or values can help to alleviate depressive symptoms. Empathic exploration of internal and external experiences, such as emotions, thoughts, reactions, behaviors, communication, and interactions, is combined with judicious exploration of interpersonal dynamics that may emerge in the therapeutic relationship itself. “Plain old therapy” techniques as elaborated in psychodynamic (

69) and mentalizing-based treatments (

70,

71) can be helpfully integrated within the time-limited structure of IPT for patients with social deficits, comorbid personality disorders, and interpersonal sensitivity (

72).

Other IPT Therapeutic Strategies

Communication Analysis is a helpful therapeutic strategy used in all focal areas to explore distressing interactions that are associated with worsening symptoms. By unpacking specific examples of conversations and exploring an interaction, communication analysis creates the space to reflect and identify problems such as misunderstandings, communicating in ways that inadvertently fuel tensions, or having a lack of empathy. Using role plays or exploratory questions, such as asking a patient, “What would you like this person to understand?” can generate insight and ideas for change. In the process of communication analysis, a patient can discover and express more clearly his or her feelings and expectations. These can then be validated by the therapist, further explored, and sometimes revised. In this way, communication analysis is a collaborative means to improving communication behaviors, not just of recollecting troubling interactions.

Recruiting and Utilizing Social Supports

Regardless of the focal area, IPT promotes patients’ recruiting and utilizing helpful psychosocial supports, such as family members, friends, colleagues, or community members. The goal is to help patients to gain comfort, understanding, and help from others, as the association of interpersonal support and psychological well-being has been well established (

73).

Termination Phase of IPT

The IPT concluding phase guidelines can be generalized to many therapeutic contexts (e.g., outpatient clinic or discharge from an inpatient or day hospital setting) and can provide a helpful set of therapeutic actions to consolidate gains and plan for the event of possible relapse. In the final 1–2 sessions, the therapist invites the patient to reflect on his or her experience of treatment and what he or she is taking away from the therapy. This reflection might include reviewing strategies to understand and cope with future stressors and use social supports, and perspectives on how the patient or his or her situation may have changed. Early signs of relapse are reviewed, and a contingency plan for intervention is created. By explicitly attending to this process of “saying goodbye” in treatment, acknowledging the work a patient has done and feelings or worries about ending therapy, the termination phase tasks provide therapeutic opportunities to empathically support the patient’s self-efficacy and improved coping strategies.

As with all therapeutic treatments, it should be noted that IPT does not work for all patients. Research about “what works best for whom” (

74), and meta-analyses on the effects of therapist, patient, therapeutic relationship, and treatment factors on outcomes (

75) highlight the importance of psychotherapeutic common factors, especially the therapeutic alliance. IPT process research has begun to examine what mitigates the response to treatment, including factors such as motivation, chronicity, attachment patterns of relating, and interpersonal problems (

76–

83).

To improve IPT outcomes, simple modifications that attend to individual patient differences have been recommended. For patients with panic symptoms, these modifications include focusing on emotions, especially fear, and somatic symptoms as cues of interpersonal distress. For patients with chronic or severe depression symptoms, the course of treatment may be extended, and medication concurrently used. Other modifications include an expanded bio-psycho-social etiological case formulation, to include attachment style, culture, and self-definition (

84).

Common factors exist among all effective therapies, related to the therapeutic alliance with empathy, rapport, positive regard, genuineness, and responsiveness (

85). However, there are differences between psychotherapies—in their goals, frame, and techniques. Cognitive Behavior Therapy, also time-limited with goals of remitting symptoms of mental illnesses such as depression, differs from IPT in its focus on the links among thoughts, emotions, and behaviors with a high level of structure, and assigned between-session homework, for example, using automatic thought records, behavioral activation, and graded exposure (

86). Psychodynamic Therapy is usually open-ended in its time frame, and informed by psychoanalytic theories that privilege how the past can influence our experience of the present. During sessions, rather than choosing a specific focal area, the therapist focuses on affect and expression of feelings, identifying distressing or self-defeating patterns, with exploration of associations, dreams, and transference dynamics (how we may project expectations from past relationships into present ones including within the therapeutic alliance). The goals of psychodynamic therapy include personality change and improved intimacy in relationships (

87,

88). Supportive Therapy differs from IPT in that it does not have a specific focus on relationships or interpersonal problems, but rather on coping, building self-esteem, and reducing anxiety (

89).

In conclusion, IPT is a powerfully helpful time-limited treatment for depression, across the lifespan and in differing cultures. It provides a clear structure with phase and focus-specific guidelines. IPT has been successfully used to treat depression, bulimia, and binge-eating disorders, and as an adjunctive treatment for bipolar disorder. There is growing evidence for its effectiveness in addressing other psychiatric problems, such as posttraumatic stress, and its use in differing formats, such as by telephone or Internet. Even with complex and chronically ill patients, such as those frequently seen in community-based “real world” settings, IPT’s relationally-focused principles and guidelines are easily integrated and modified to improve outcomes in mental health care.