Treatment Strategies and Evidence

The “gold standard” method for evaluating the efficacy of psychotherapies is the randomized controlled trial (RCT). Yet, controlled trial research in anorexia nervosa and among children with eating disorders in general is hampered by methodological challenges. The acute prospect of mortality from anorexia nervosa and the long-term risks to growth and physical development in children preclude the use of a no-treatment or delayed treatment control group, complicating the evaluation of specific treatment effects (

11). For anorexia nervosa, high treatment drop out (∼50%) can compromise randomization, and the egosyntonicity of the illness can lead to low treatment adherence. In some RCTs, uncontrolled background treatments (i.e., inpatient care) are present (

12). To understand the current state of the evidence for psychotherapies in eating disorders, a multipronged approach that considers RCTs or other systematic research studies, clinical practice guidelines, and emerging interventions is worthwhile. This approach informs this review.

Questions and Controversy

Despite the existence of empirically supported treatments, it is important to be aware that there are wide ranges of outcomes—many fully successful and some quite chronic with multiple hospitalizations. For adults with anorexia nervosa, success at posttreatment is less than 25%, largely because of substantial drop out (

17). For bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder in adults, the symptom remission rate associated with the leading psychotherapies is around 50% (for those completing treatment) (

22,

26). About half of the young people with anorexia nervosa treated with family-based treatment remit (

40).

Few prognostic factors for treatment outcome have been reliably identified. For anorexia nervosa, a longer duration of illness and longer duration of treatment and/or need for inpatient hospitalization are associated with worse outcomes (

49). Predictors of relapse have included a lower desired body weight and treatment at a generalist (rather than specialist) clinic (

49). A wide range of dietary choices is also associated with positive prognosis in anorexia nervosa suggesting less rigidity associated with food intake (

50). For bulimia nervosa, psychiatric comorbidity and comorbid symptom severity predict poorer outcomes, and as yet, not much is known about prognostic factors for binge eating disorder (

49). Clearly, there is room for improvement of treatment outcomes and for understanding prognostic factors.

Treatment refusal among patients with anorexia nervosa is frequently encountered. Clinical decision-making in this context involves ethical and medico-legal considerations that vary from jurisdiction to jurisdiction. The vantage points are complex: on the one hand, compelling a person to treatment (i.e., through a compulsive treatment order or legal guardianship) deprives liberty and may violate confidentiality and privacy, yet it is typically a last resort to preserve life. There is a general consensus supporting the use of legal interventions if the eating disorder poses mortal danger (

14). Engaging and retaining adults with anorexia nervosa in treatment is of primary importance, although challenging given that the core treatment goal (i.e., weight gain) is the outcome that they most fear.

A robust debate within the field pertains to the degree to which FBT has become accepted as the treatment of choice for anorexia nervosa in children and adolescents. A recent debate feature captures some of these viewpoints, which the reader may find worth exploring (

51,

52).

Binge eating disorder is often associated with overweight and obesity, which leads to a question about the degree to which psychotherapy should incorporate weight loss or weight management strategies. The primary clinical outcome for binge eating disorder is binge abstinence, yet in the context of overweight and obesity, weight and BMI are important secondary outcomes. Weight losses with psychotherapy have been modest and variable, with BWL having a slightly larger effect than CBT (

53). As patients are typically on the path of gaining weight prior to treatment (

54), psychotherapy interventions appear to prevent additional weight gain at least in the short term (

53,

54). There is no evidence substantiating the concern that moderate caloric restriction in BWL triggers binge eating (

37). Although many individuals with binge eating disorder seek weight loss as a therapeutic goal, others believe that a lifelong focus on weight loss has contributed to and perpetuated their disorder, and contend that a therapeutic focus on decreasing weight stigma and healthy lifestyles is preferred (

55).

As new technologies develop and the Internet grows, technology is increasingly being used to enhance the delivery, accessibility, and cost-effectiveness of psychotherapy (

56). Internet-based therapies for eating disorders, virtual reality-based treatments, telemedicine, and smartphone applications (e.g., self-monitoring records), are examples of current applications in either research or practice. Benefits are foreseeable for individuals or health professionals with limited access to specialists, or when treatment experience can be enhanced by technology integration, such as making homework more convenient and reducing stigma around treatment-seeking.

Recommendations from the Authors

A physician should always be part of the treatment team to manage general medical issues related to an eating disorder, and pharmacotherapy may play a crucial role in some presentations, delivered by a primary care practitioner or psychiatrist when more severe or recalcitrant pathology and/or psychiatric comorbidity are present (

13,

14). The preferred setting for psychotherapy is the least restrictive setting, to reduce disruption to the patient’s family, social, academic, and work activities. However, clinical deterioration should raise attention to the need for a higher level of care.

Currently, for adults with anorexia nervosa, there is no clear evidence for the efficacy of any approach, and reasonable choices include CBT, IPT, cognitive analytic therapy, or supportive interventions such as specialist supportive clinical management—bearing in mind that psychotherapy may be optimally effective after renourishment is well underway and that supportive therapy may be optimal in the underweight state. For bulimia nervosa and binge eating disorder, CBT and/or antidepressant medication are considered to be first line treatments, and IPT and DBT (and BWL for binge eating disorder) are acceptable second line approaches. For anorexia nervosa in young people, FBT or family interventions that specifically target the eating disorder are appropriate.

Beyond the specific components of the interventions, the therapeutic stance should balance empathy and therapeutic firmness. Many eating disorder behaviors are perplexing, for instance, intense and seemingly irrational anxiety regarding forbidden foods and secrecy and deception regarding binge eating. Clinicians should guard against their own preconceptions and misperceptions. It is helpful to understand the ambivalence and fears the patient holds regarding recovery, and to reframe treatment resistance as part of the illness, not part of the individual (

57). Working with people with eating disorders can be a very rewarding experience, despite being challenging at times, with treatment offering abundant prospects for the long-term physical and psychological health of these individuals. Additional resources are listed in

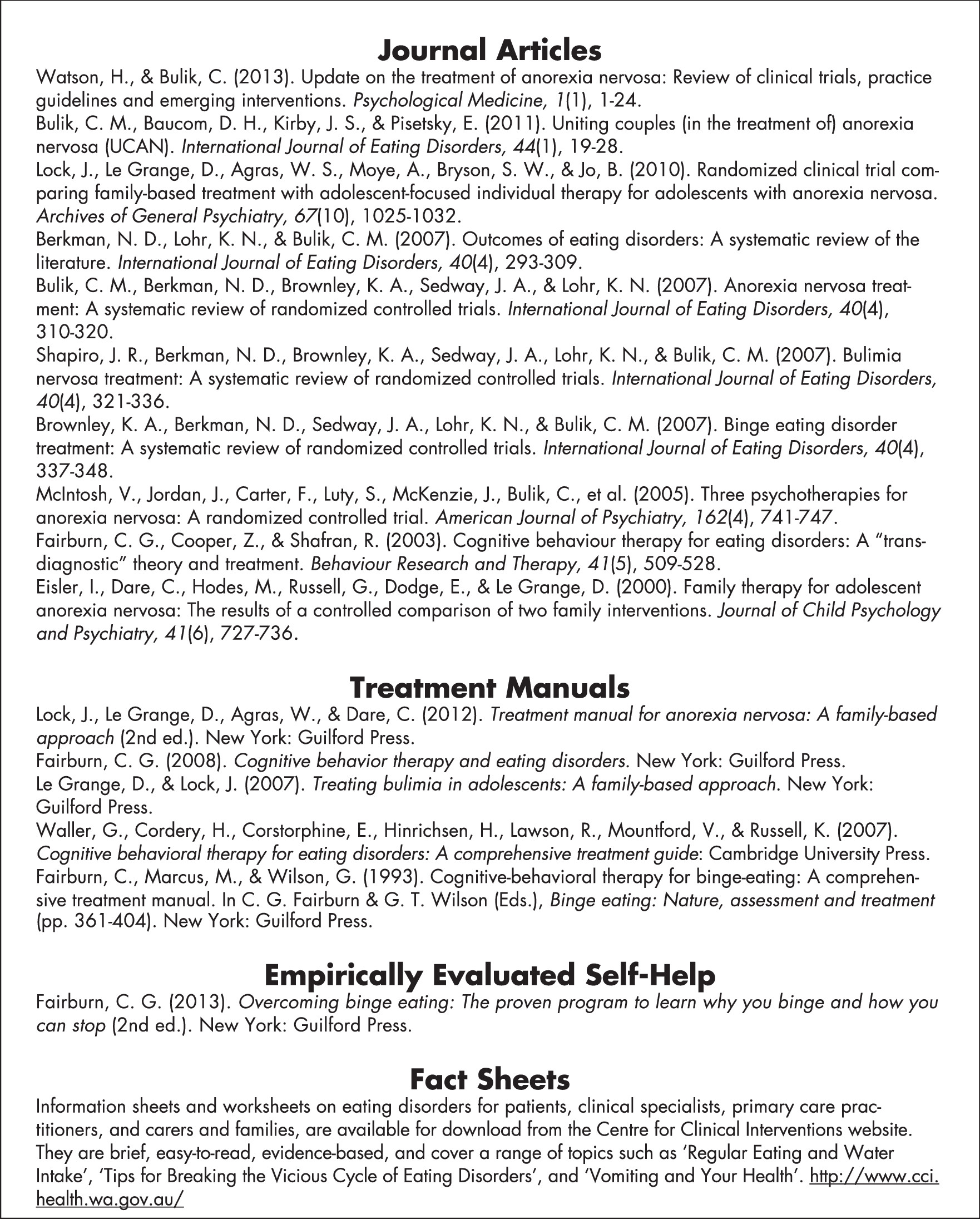

Figure 1.