As summarized in the companion article for this report (

1), bipolar disorder is common, chronic, and associated with substantial morbidity and health care costs. As in the management of other chronic medical illnesses, the cornerstone of bipolar management is evidence-based pharmacotherapy (

2). However, there is a substantial gap between the efficacy of interventions seen in clinical trials and their effectiveness in real-world practice (

3–

10). Modest response rates in recent large effectiveness trials suggest that medication strategies alone will not be sufficient to close this gap for bipolar disorder (

11), schizophrenia (

12), or depression (

13,

14).

Chronic care models for medical illness improve clinical and functional outcome by emphasizing continuity of care over episodic response to acute symptoms (

15). They reorganize services to enhance patient self-management skills, support provider decision making, and improve system responsiveness to patient needs (

15–

17). For depression treated in primary care, such models improve acute (

18) and long-term (

19,

20) outcome and are cost-effective (

21).

However, these models are virtually unstudied for chronic mental illnesses. Assertive community treatment programs have been the predominant model for such illnesses, proving effective and cost-effective (

22–

24). However, organizational complexity and high start-up costs limit their dissemination (

25–

27). For bipolar disorder, cognitive-behavioral therapy (CBT) (

28–

31), family therapy (

32), or psychoeducation (

33,

34) added to pharmacotherapy have shown benefit in maintenance trials, and CBT may be cost-effective (

35). However, not all studies have shown effects on primary outcome measures (

30,

31), and effects are particularly attenuated among more impaired individuals (

31).

Conceptually, chronic care models share with assertive community treatment programs and psychotherapeutic interventions an emphasis on patient empowerment and self-management skills. Operationally, however, these models are distinct from assertive community treatment programs by being exclusively clinic based, with more easily attainable patient-to-staff ratios (

5,

15–

17,

36). These models are operationally distinct from psychotherapeutic interventions by explicitly reorganizing health care services (

5,

15–

17,

36). An open study in a Veterans Affairs medical center (VAMC) (

37) and a concurrent trial in a staff-model health maintenance organization (HMO) (

38) indicate that such models might be feasible and effective in treating bipolar disorder.

This report describes primary outcomes of a three-year randomized controlled single-blind trial. A collaborative chronic care model is compared with usual care for bipolar disorder across 11 VAMCs for a severely ill, frequently hospitalized sample with high rates of current psychiatric and medical comorbidity. We hypothesized that the intervention would improve clinical and functional outcome, with benefits accruing over three years—consistent with social learning theory (

16,

36)—and would reduce total direct all-treatment costs from the VA perspective. The trial, described in detail in the companion article (

1), was structured from the outset to emphasize effectiveness components in order to maximize the generalizability of results for dissemination (

5–

9).

Methods

Site Selection, Intake, Randomization, and Baseline Assessment

Between January 1, 1997, and December 31, 2000, all patients with suspected bipolar disorder admitted to 11 sites’ acute psychiatric wards were screened as described in part I of this report (

1). Intake assessment included informed consent approved by appropriate institutional review boards followed by administration of the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV (SCID) (

39). Participants were randomly assigned at discharge to a three-year follow-up with the intervention or with usual care. Randomization was accomplished with a concealed computerized telephonic system used in blocks of two to four participants within site, stratified by presence or absence of assisted living support (see

Figure 1 of the companion article in this issue) (

1).

Outcome Measures

Clinical variables were derived from the Longitudinal Interval Follow-Up Examination (

5,

40) administered every eight weeks, during which participant recall remains intact (

41). This semistructured interview uses timeline follow-back methodology to provide weekly psychiatric symptom ratings (PSRs) for mania and depression based on the number of

DSM-IV criteria endorsed: no or minimal symptoms (PSR 1 to 2), subthreshold symptoms (PSR 3 to 4), or episode (PSR 5 to 6). Twenty interviews quantified manic and depressive symptoms for each of 156 weeks.

Social role function was measured by the Social Adjustment Scale–II (

5,

42) administered every eight weeks. This interview scores impairment for each period for overall function and for five specific roles (work, social and leisure, marital, parental, and extended family). Possible ratings of impairment are none, rated 1; minimal, rated 2; moderate, rated 3; severe, rated 4; very severe, rated 5. Twenty eight-week ratings covered 156 weeks.

Mental and physical quality of life were assessed at 24-week intervals with the Medical Outcomes Study 36-item Short Form Health Survey mental component score (MCS) and physical component score (PCS) (

43). (For comparison, the U.S. population has a mean±SD of 50±10 for each.) Treatment satisfaction (

44) was also assessed with a validated instrument at 24-week intervals (score range of 12 to 72). Intensity of bipolar-specific pharmacotherapy was determined by an adaptation of the National Institute of Mental Health Collaborative Study instrument (

45), which was updated for current practices in treatment of bipolar disorder (

36). This measure was completed every 24 weeks with the best available data (participant’s report plus chart review) to determine the maximal levels and doses of antimanic, antidepressant, and mood-stabilizing medications that the participant received. The index range is 0 to 5, with 3 or higher considered adequate (

36).

Intervention

The Bipolar Disorders Program intervention is described in detail in part I of this report (

1). Briefly, the intervention uses a specialty team (

17) consisting of a nurse care coordinator and a psychiatrist functioning in the outpatient clinic. They provide care via regular appointments, which are supplemented as needed by phone and clinic contact. The intervention is clinic based and staffed with a .5 full-time-equivalent (FTE) nurse and a .25 FTE psychiatrist managing 45 to 50 patients (including additional patients with bipolar-spectrum disorders not randomly assigned). After-hours care and mobile community outreach are not part of the intervention. The three specific components include enhancement of patients’ skill in self-managing their illness via group psychoeducation (

46–

48); support to providers by distilling to a single algorithm and reference manual the VA Bipolar Practice Guidelines (

36,

49), with the goal of enhancing evidence-based pharmacotherapy; and staffing a nurse care coordinator to enhance access to care and continuity of care according to procedures outlined in a manual that details the intervention. The care manager also facilitates information flow to the psychiatrist (laboratory results, clinical assessments, and to-do lists).

No other care was changed. Specialty mental health and medical-surgical referrals were made or continued as needed.

Usual Care

Participants who were randomly assigned to usual care continued with their previous psychiatrist or were assigned one if new to the VA. The clinicians of both groups—those assigned to the intervention and those assigned to usual care—received intake data from the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV and functioned in the same mental health clinic. No intervention clinicians cared for participant assigned to usual care.

Data Reduction

Syndromal outcome consisted of the percentage of weeks in each of the three years that participants met

DSM-IV criteria for manic episodes, depressive episodes, or any episode (PSR=5 to 6). Values were square-root transformed to stabilize variance. Mixed episodes (<2 percent of episode weeks) were counted as both syndromal mania and depression. Manic and hypomanic episodes were pooled for analysis (referred to collectively as “manic episodes” hereinafter) as supported by previous studies (

41,

50). Symptomatic outcome consisted of mean PSRs for mania and depression (reflecting both episodes and subsyndromal symptoms) for each eight-week interview period (N=20 ratings). Twenty SAS-II functional ratings, seven MCS and PCS scores, seven treatment satisfaction ratings, and seven pharmacotherapy ratings characterized those domains.

The total direct all-treatment costs from the VA economic perspective (

51) included all treatment costs (inpatient, outpatient, pharmacy, other; mental health, medical-surgical, other). They did not include lost wages and other indirect costs. Costs were derived from the VA National Patient Care Database and Pharmacy Benefits Management Package (

www.virec.research.med.va.gov/datasourcesname/datanames.htm), supplemented by interview-based query every eight weeks for non-VA service use (

1), and allocated to 20 eight-week periods starting with the day of randomization. Costs were adjusted annually for inflation with the consumer price index (

www.bls.gov/cpi/home.htm) to express all costs in 2004 dollars. Costs incurred in different years were discounted at a rate of 3 percent.

Data Analysis

The study chair and sites remained blind to outcome until follow-up was complete. Analyses were based on intention to treat and used mixed-effects models (SAS PROC MIXED), which are less prone to bias caused by dropouts than last-observation-carried-forward methods (

52).

The primary clinical outcome (

1,

5) was weeks in any episode. For the three distinct prespecified variables—weeks in episode, overall function, and costs—alpha was set at .05. To account for multiple comparisons among secondary analyses, alpha was set at .01, with .01 to .05 considered trend level (

53). For significant analyses, the more clinically meaningful effect size (

54) is presented.

Our a priori hypotheses proposed that intervention benefits would accrue gradually because participant self-management skills and treatment alliance would require time to develop (

5,

36)—an approach taken by other chronic care model investigators (

55). Accordingly, we used random effects repeated-measures analyses for all outcomes, estimating the intervention effect with a linear-in-time variable to reflect a treatment effect growing linearly in time after randomization. We estimated effects by first assuming a linear time trend in group means, then again allowing an arbitrary time profile. Because results from both methods did not differ, linear time trends are presented here. In three instances (MCS, PCS, and satisfaction), inspection of observed compared with expected plots and Akaike information criterion (

56) indicated that a simple constant-in-time model clearly fit better than a time trend model. That is, treatment was associated with a constant difference from the first measurement rather than gradual accrual of effect. This alternative model was implemented by a dummy variable for treatment.

Each model included site, stratum, and relevant baseline score as effects; random effects included intercept and time. The repeated measure was time. In addition to random effects, we allowed covariance between a participant’s measurements to vary (SAS PROC MIXED “spatial power” option).

The target sample size was 382, with the analysis projecting 25 percent dropout completely at random without any data, to provide two-tailed significance of .05 and power of .90 for symptomatic outcome. The study randomly assigned 330 participants across 11 sites. All participants for whom any follow-up data were available were included in the analyses (N=306 of 330, or 93 percent of those randomly assigned).

Costs were compared with repeated-measures analysis of the mean difference between the groups (

57). We report the difference in mean costs and 95 percent confidence interval (CI), with p values calculated by a non-parametric bootstrap procedure (

58).

Results

Sample Characteristics and Retention

The trial recruited a severely ill, highly comorbid sample, and the intervention was implemented with excellent fidelity (

1). Participants in the intervention and usual care arms of the study did not differ on demographic or clinical characteristics except that intervention participants were somewhat older, less likely to have had a prior suicide attempt, and more likely to have a diagnosis of a substance use disorder over their lifetime. Current substance disorder prevalence did not differ between groups.

The overall protocol completion rate to week 156 was 80 percent and did not differ by survival analysis between intervention and usual care (respectively, 75 percent and 85 percent) or by mean retention in the protocol (123.5±50.4 compared with 120.2±52.0 weeks). Early terminators did not differ from completers in gender, age, homelessness, prior suicide attempts, or psychosis. Ninety-six percent of all cost datapoints were available.

Deaths did not differ (intervention, 12 deaths among 166 participants, or 7 percent; usual care, eight deaths among 164, or 5 percent). There were 12 medical deaths, four accidents, one suicide (usual care participant), and three deaths from unknown causes.

Outcomes

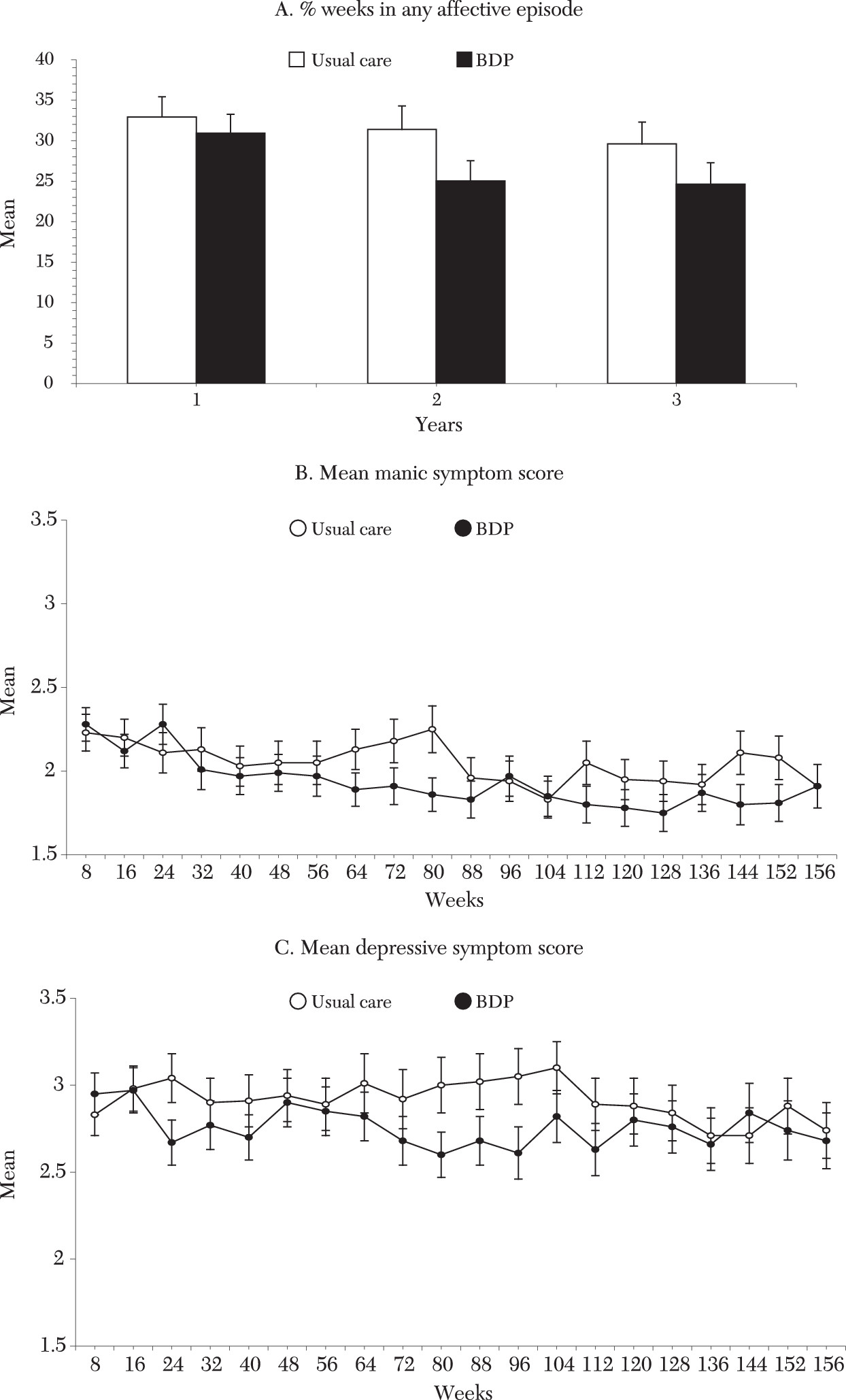

Tables 1 and

2 summarize the analyses. Syndromal outcome analyses indicated that intervention treatment was associated with a significant reduction in weeks of an affective episode (

Figure 1A), including reduction in weeks of manic episodes, and a nonsignificant reduction in weeks of depression. These effects translated to 6.2 fewer weeks in an affective episode over three years compared with usual care (CI=−.3 to −12.5 weeks), including 4.5 fewer weeks of manic episodes (CI=−.8 to −8.0 weeks). In percentage terms (difference in raw number of weeks in episode for usual care minus intervention, divided by weeks in episode for usual care), the intervention reduced weeks in episode by 14 percent (6.9/48.8), weeks manic by 23 percent (3.6/15.6), and weeks depressed by 11 percent (4.0/35.9). Differences in symptomatic outcome and mean manic and depressive symptom levels (

Figure 1B and C, respectively) did not reach significance (effect sizes of .16 and .17).

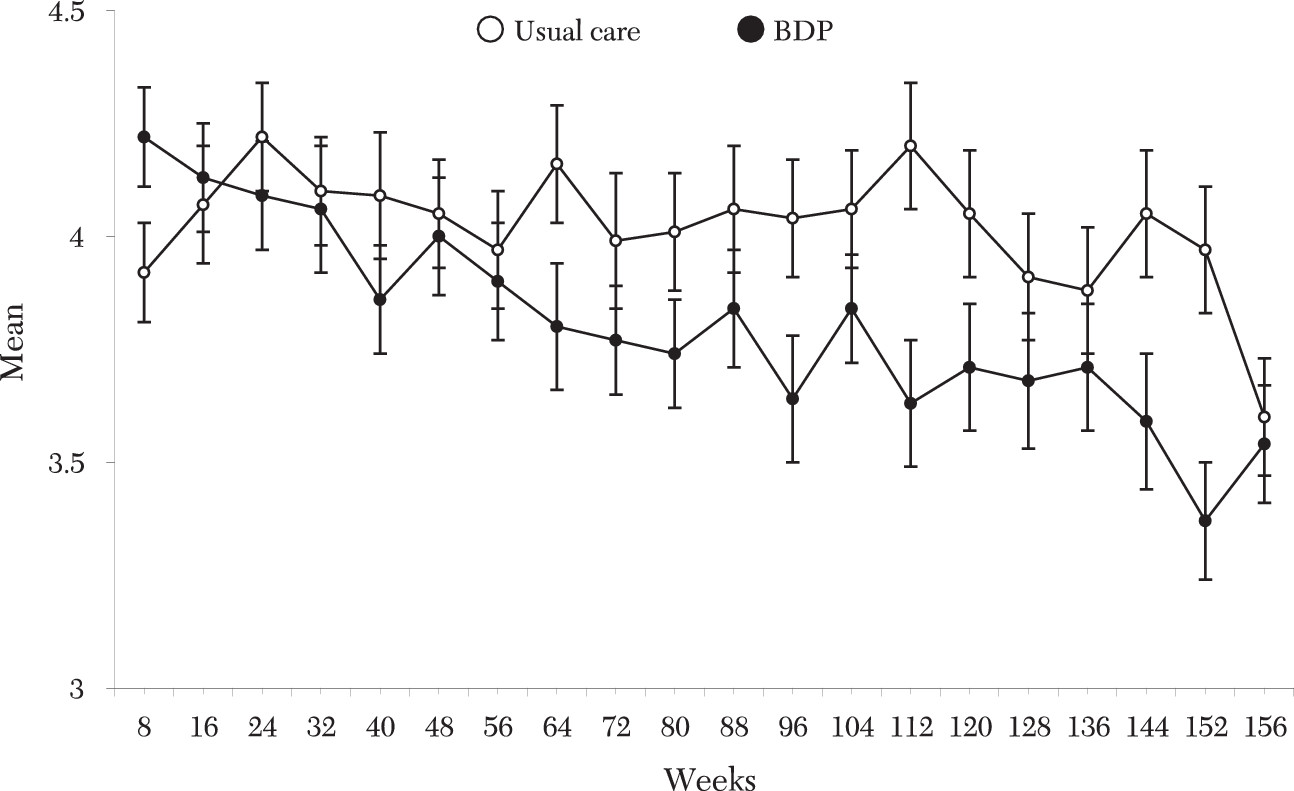

Treatment in the intervention significantly improved overall social function (

Figure 2), including work, parental, and extended-family roles, but not social and leisure or marital function. Mental, but not physical, quality of life was significantly improved among participants in the intervention group from the assessment.

Treatment satisfaction was higher in the intervention group from the first six-month assessment. Pharmacotherapy intensity did not differ between treatment arms and was adequate (

36) over three years for both the intervention and usual care.

Time Course of Effects

The time course of effects was explored by applying identical linear-in-time models to major outcome variables at year 1 and year 2. At one year no significant clinical or functional effects were evident. By two years reductions began to emerge in weeks in episode (p=.07) and weeks depressed (p=.07). By this time mean depressive symptom reductions approached significance (p=.02), with significant or trend effects in overall (p=.004), work (p=.02), parental (p=.02), and extended-family (p=.04) function.

Site main effects, but not site time-course effects, were significant for most variables (F=1.8 to 10.8, p<.02 to p<.001). This finding represents a mean of two sites differing from the overall effect on most analyses, although no site was consistently different. There were no stratum effects.

Direct all-Treatment Costs

Mean intervention three-year costs were $61,398 (CI=$52,037 to $71,787) compared with $64,379 (CI=$55,031 to $73,695) in costs for usual care. The difference point estimate was −$2,981 (CI=−$16,030 to $10,601). Nonsignificant increases in outpatient costs in the intervention arm ($20,740 compared with $20,091, difference $648; CI=−$2,994 to $4,101) were more than offset by reductions in inpatient costs ($40,658 compared with $44,288, difference −$3,629; CI= −$15,503 to $9,014), including both psychiatric inpatient costs ($27,428 compared with $30,665, difference −$3,337; CI= −$12,512 to $6,067) and medical-surgical inpatient costs ($13,230 compared with $13,523, difference −$293; CI=−$6,928 to $5,983).

The temporal pattern of hospitalization rates paralleled clinical improvements, although treatment arms did not differ in overall number of hospital days (38.2 compared with 41.8, difference −3.7; CI=−16.1 to 9.3). Specifically, there were no differences between treatment arms in year 1, but the proportion psychiatrically hospitalized in year 2 tended to be lower in the intervention than for usual care (35 percent compared with 47 percent; Fisher’s exact p=.05), with a near-significant difference in year 3 (28 percent compared with 38 percent; p=.08). Similarly, rates of hospitalization for any reason tended to be lower among patients in the intervention group in year 2 (44 percent compared with 53 percent; p=.10) and in year 3 (34 percent compared with 48 percent; p=.02).

Discussion

Comparison with Other Relevant Trials

The Bipolar Disorders Program intervention improved long-term clinical and functional outcome for a severely ill and highly comorbid sample likely to be seen in clinical practice. This intervention was tested under realistic clinical conditions in an effectiveness trial design (

5–

10). The intervention reduced weeks in affective episode and weeks manic, though not weeks depressed or mean symptoms, and was cost-neutral. Broad-based functional and quality-of-life gains occurred despite a nonsignificant reduction in weeks depressed or mean symptoms; this finding is particularly notable because most studies indicate that ongoing depression is the strongest correlate of functional deficits in bipolar disorder (

41,

59). Most clinical and functional improvements accrued in years 2 and 3, consistent with social learning theory (

16,

36) and a priori hypotheses (

5).

Results are consistent with a concurrent two-year trial of a similar collaborative chronic care model for bipolar disorder (

60). Compared with usual care in a staff-model HMO, that intervention also demonstrated significant effects on mania but not depression, at an incremental cost of $1,251 (

38). Thus two trials conducted concurrently among very different populations and systems support the feasibility and effectiveness of collaborative chronic care models for bipolar disorder. A one-year public-sector guideline-implementation trial with provider education plus clinical coordinators (35 patients per FTE) compared with usual care also showed effects on global psychopathology and mania by three months, without significant differences in depressive symptoms or function (

61).

Results also compare favorably with those of with several bipolar pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy maintenance trials. Over 18 months, lithium or lamotrigine was associated with “less worsening” of mean depression than placebo, without effects on mania (

62). A 30-month CBT trial reported fewer days ill and days depressed compared with a control group after 12 months, without effects on mean depressive symptoms at 18, 24, or 30 months; manic symptoms were reduced only at 30 months (

28,

29). Another CBT trial showed initial improvement in depressive symptoms compared with treatment as usual but no difference at 12 to 18 months and no effect on manic symptoms (

30). Notably, the lone CBT trial with an effectiveness design showed no primary effect due to inclusion of more severely ill and complicated individuals likely to be encountered in clinical practice (

31). Regarding function, neither lithium nor lamotrigine provided benefit compared with placebo over 18 months (

63), although another trial found “less worsening” with lithium or lamotrigine (

62). CBT (

24,

25) and psychoeducation (

27) effects on function reached significance only after one year.

In light of these modest long-term trial effects, and the potential impact of even minor clinical improvements in bipolar disorder (

64), we recall Cohen’s caution against judging statistical effect sizes without clinical context (

65). In complex, real-world samples with serious mental illness, incremental gains are likely to reflect clinically meaningful benefit, as we are reminded by modest response rates in the Sequenced Treatment Alternatives to Relieve Depression (STAR

*D) trial (17 to 31 percent) (

13,

14), the Clinical Antipsychotic Trials of Intervention Effectiveness (CATIE; 18 to 31 percent) (

12), and the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorders (STEP-BD) refractory bipolar depression (5 to 24 percent) (

11). Data from the two long-term collaborative chronic care trials for bipolar disorder suggest that these models may provide means to augment such medication effects, especially if their impact on depressive symptoms can be amplified.

Possible Mechanisms

Results indicate that pharmacotherapy was adequate and did not differ across treatments. It is possible (

33,

34), but not likely (

31), that psychoeducation alone enhanced outcome for this severely ill sample. More likely, multiple components contributed (

15), with improved access and continuity facilitating pharmacotherapy and patient self-management. Enhanced access to and continuity of care is consistent with somewhat higher intervention outpatient costs and the fact that 92 percent of unscheduled mental health care for intervention participants was rendered by clinicians with whom they had ongoing treatment relationships (

1). Of note, though, is that outpatient costs did not rise sharply, which is consistent with experience in open-access medical clinics (

66). Perhaps anticipatory planning and use of telephonic care (

67) mitigated usage, which would be consistent with our finding in the initial open trial demonstrating significantly fewer emergency room and psychiatric triage visits with the intervention (

37).

This study examined one of the few bipolar controlled trials to demonstrate functional benefits. Intriguingly, these effects were seen without significant reductions in depressive symptoms. It is possible that only reductions in mania and modest reductions in depressive symptoms were necessary for significant functional gains. Alternatively, the combination of psychoeducation and facilitated collaboration with providers may have allowed participants to manage their lives more effectively despite ongoing symptoms.

Limitations

The design was single-blind because treatment assignment could not be concealed from participants. However, interviewer reliability was high and effects were seen across multiple domains. Furthermore, within-site randomization would, if anything, reduce differences. Moreover, changing caregivers in treatment trials, more frequent with intervention participants, has itself been associated with worse outcome for bipolar disorder (

68). Although overall significant intervention effects were accompanied by intersite heterogeneity, as in other system reorganization studies (

69), no site consistently differed across measures.

Regarding VA-specific factors, costs were calculated from the VA economic perspective. Such data serve as the basis for administrative decision making throughout the VA; incremental cost-utility analyses are under way. All study participants were veterans, and most were men. However, high rates of suicidality, psychosis, and medical and psychiatric comorbidity resemble or exceed those encountered among other severely ill populations (

1). Historically underserved minority populations were well represented (

5).

Conclusions

Practice guidelines have endorsed chronic care models for bipolar disorder on the basis of face validity plus studies in medical illness and depression treated in primary care (

48). Two large effectiveness trials totaling over 700 participants—this trial in a highly ill, frequently hospitalized sample and another with an HMO population-based sample(38)—now provide empirical support for this recommendation. This trial indicates that broad-based effects on function and quality of life also can be achieved.

Notably, these trials demonstrate that individuals with bipolar disorder can participate successfully in, and benefit from, highly collaborative chronic care models. These trials extend the utility of such models from depression treated in primary care to severe, chronic mental illness treated in the mental health sector. They further contravene the “paternalistic assumptions” about the insight and self-management capabilities of individuals with severe mental illness that have traditionally separated mental from other medical illnesses (

70).

Will collaborative chronic care models for bipolar disorder also have effects in systems less integrated than VAMCs or HMOs? Studies of chronic medical illnesses (

15) and depression treated in primary care (

18–

21) suggest that this will be a productive line of investigation.