Bipolar disorder is one of the most severely disabling psychiatric disorders (

1), characterized by manic, hypomanic, depressive, and mixed syndromal episodes, as well as persistent interepisodic mood symptoms and high levels of vocational impairment (

2,

3). As of 2009, the estimated direct and indirect costs of bipolar disorder in the United States are $151 billion annually (

4). Long-term outcomes, even with the best available guideline-consistent treatments, tend to be poor for many patients (

5).

Although many medications are now approved for acute and maintenance treatment of bipolar disorder, the gold standard for many years has been lithium salts. Nevertheless, the use of lithium, especially as monotherapy, has been steadily declining (

6). When clinicians do prescribe lithium, they usually give it along with other medications approved for the treatment of bipolar disorder or associated symptoms (with a median total of three medications [7]). Randomized clinical efficacy trials support combining lithium with second-generation antipsychotics (

8–

10) for acute mania or mixed episodes. The use of lithium with additional medications, however, has not been well studied, although complex combination therapy has become the de facto standard of care (

7,

11,

12).

Since lithium, even at low dosages, has potent neuro-protective properties that could be synergistic with other medications (

13,

14) and may reduce the risk of dementia (

15) there is a great public health need to compare the effectiveness of personalized flexible medication regimens with and without lower, more tolerable dosages of lithium for acute and continuation treatment. The Lithium Treatment Moderate-Dose Use Study (LiTMUS) was designed to address whether a tolerable dosage of lithium, in combination with other medications for bipolar disorder, would result in better outcomes over 6 months (

16). This comparative effectiveness study bridges the gap between rigorous but less ecologically valid placebo-controlled efficacy trials and real-world clinical practice to provide data to help clinicians make empirically based clinical decisions.

Results

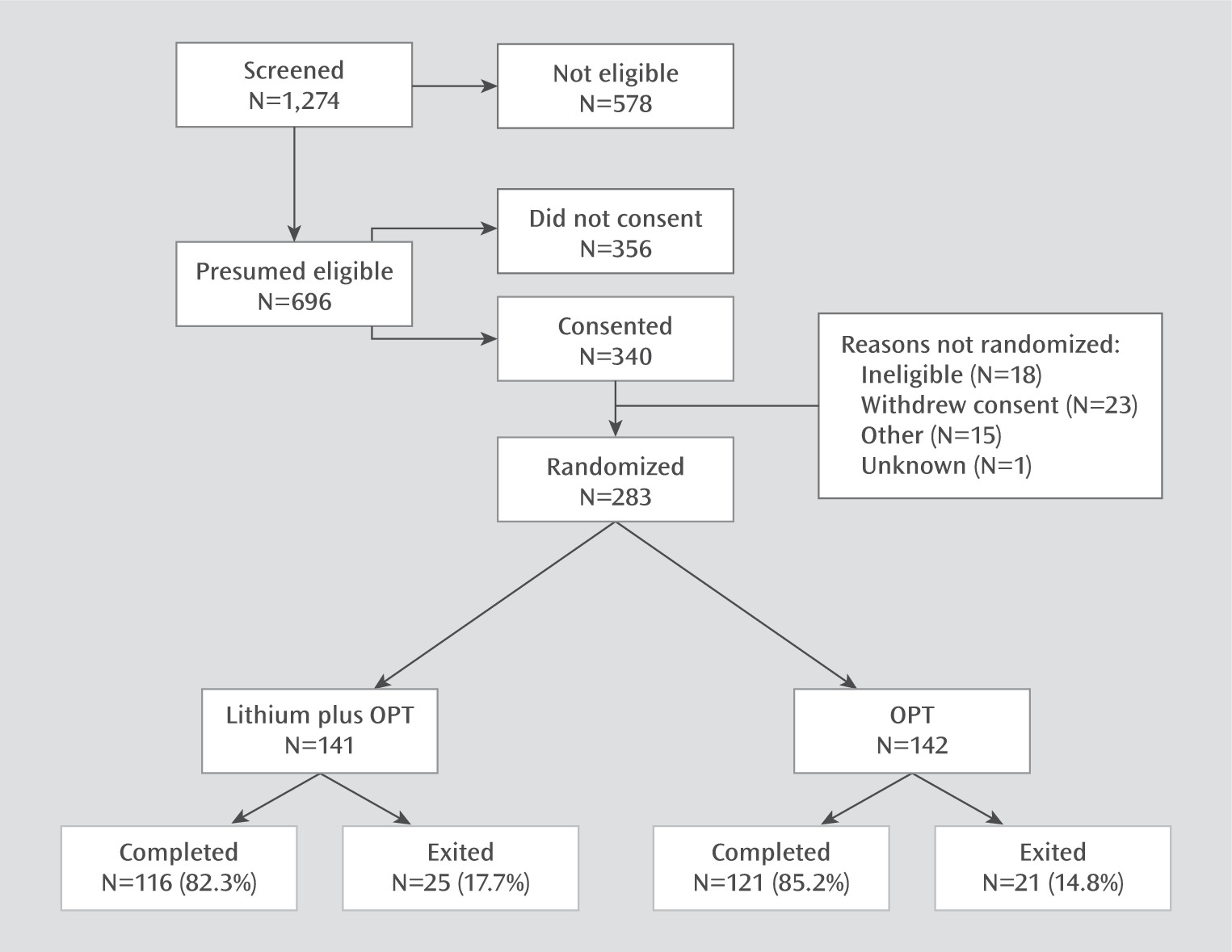

The CONSORT diagram in

Figure 1 summarizes the study’s screening, recruitment, randomization, and attrition. The participants’ baseline demographic and clinical characteristics are summarized in

Table 1. The majority of participants had bipolar I disorder (history of mania) and the remainder had bipolar II disorder (history of hypomania). Over half had a lifetime history of hospitalizations, and over 40% had a lifetime history of at least one suicide attempt.

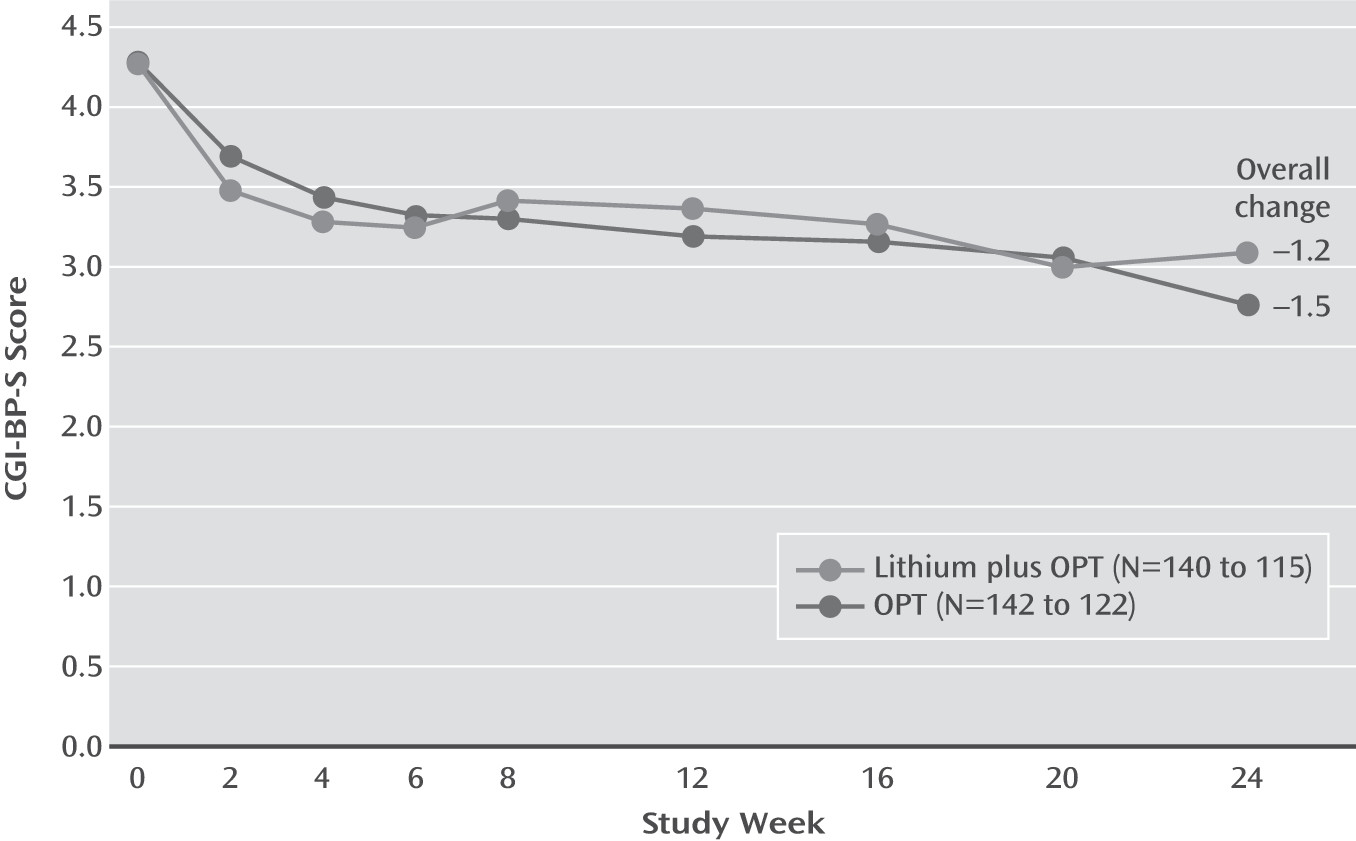

The baseline CGI-BP-S scores indicated that over 85% of participants were at least moderately ill at study entry. Participants were mostly depressed, with 87% meeting DSM-IV criteria for recurrent major depressive episodes, 63% meeting criteria for a lifetime manic episode, and 38% for a lifetime hypomanic episode. No statistically significant differences were found between the groups for any variable except that the lithium-plus-OPT group had more manic episodes during the previous year (unadjusted p=0.026) than the OPT-only group. Mean overall CGI-BP-S scores decreased 1.36 points (SD=1.44), with mean decreases of 1.22 points (SD=1.50) for the lithium-plus-OPT group and 1.48 points (SD=1.37) for the OPT-only group.

Retention in the study was 84%, with no differences between the groups. However, whereas 21% of the lithium-plus-OPT group discontinued lithium prematurely, only 2% of the OPT-only group stopped taking a mood stabilizer or otherwise violated the treatment protocol (

34). Participants took a mean of 2.59 psychiatric medications (SD=1.30), excluding lithium, over the study duration, with 2.56 medications (SD=1.33) in the lithium-plus-OPT group and 2.61 (SD=1.28) in the OPT-only group.

For patients in the lithium-plus-OPT group, lithium levels over time were 0.43 mEq/L at week 2 (N=115; median=0.40, SD=0.19, range=0.00–1.18), 0.44 mEq/L at week 12 (N=90; median=0.40, SD=0.29, range=0.00–1.60), and 0.47 mEq/L at week 24 (N=83; median=0.40, SD=0.34, range=0.00–1.80).

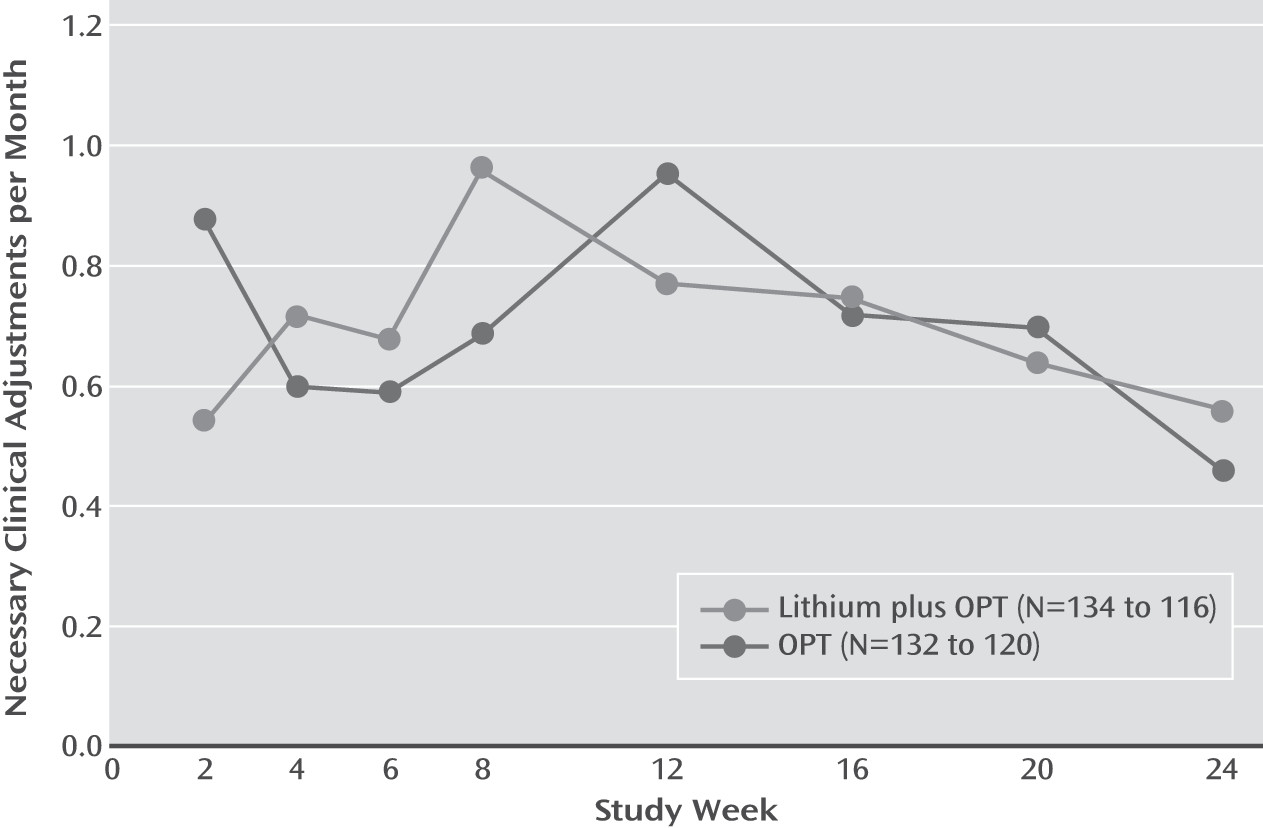

We observed no statistically significant symptomatic advantage of lithium plus OPT on CGI-BP-S scores or on necessary clinical adjustments across the 6-month study (

Figures 2 and

3). A secondary Poisson regression model also showed no significant difference in log(necessary clinical adjustments/month+1) between the treatment groups, using log months follow-up as an offset. Necessary clinical adjustments changed a mean of 0.99 (SD=0.86) over 24 weeks, with a mean of 1.01 (SD=0.85) necessary clinical adjustments for the lithium-plus-OPT group and 0.98 (SD=0.87) for the OPT-only group.

No statistically significant differences were found between groups in the proportion of patients who experienced sustained remission (26.5% overall). Likewise, the groups had similar outcomes across secondary clinical measures, including depressive symptoms and manic symptoms. MADRS scores decreased by a mean of 8.53 points (SD=12.95), with 8.20 points (SD=12.29) for the lithium-plus-OPT group and 8.84 points (SD=13.59) for the OPT-only group. YMRS scores decreased by a mean of 6.06 points (SD=9.31), with 6.35 points (SD=10.09) for the lithium-plus-OPT group and 5.79 points (SD=8.45) for the OPT-only group. Notably, fewer patients in the lithium-plus-OPT group received second-generation antipsychotics compared with patients in the OPT-only group (48.3% and 62.5%, respectively; p=0.028).

No differences were observed in treatment-emergent suicidal ideation (for those with a baseline score on the Beck Scale for Suicide Ideation of 0) or exacerbation of baseline suicidal ideation (for those with baseline score >0). Scale for Suicide Ideation scores improved a mean of 0.92 points (SD=3.94), with 0.73 points (SD=4.12) for the lithium-plus-OPT group and 1.10 (SD=3.77) for the OPT-only group. Serious adverse events, including suicidal behavior or psychiatric hospitalization due to suicide risk, were similar between the two groups. No deaths occurred.

Predictor and moderator analyses did not reveal any statistically significant associations between baseline variables and outcome.

Discussion

In this comparative effectiveness study, we used minimal inclusion and exclusion criteria to recruit a representative group of outpatients with bipolar disorder who not only were substantially symptomatic but also had multiple psychiatric comorbid conditions. Most participants had a history of psychiatric hospitalizations and suicide attempts; many were disabled or unemployed. However, despite being ill for many years, most participants had never received an adequate course of lithium therapy during the current episode.

Overall, about one-quarter of participants in both groups achieved remission (as defined by CGI-BP-S score <2 for 2 months) along with improvements of 30% to 60% in baseline mood symptoms after 6 months of evidence-based, guideline-concordant treatment provided in specialty clinics. On the primary outcome measures, CGI-BP-S score and necessary clinical adjustments, lithium plus OPT conferred no clinical symptomatic advantage compared with OPT alone.

It is of particular interest that the lithium-plus-OPT group had, however, less exposure to second-generation antipsychotics (an absolute difference of about 14%; in terms of relative risk, patients treated with lithium plus OPT were about 23% less likely to take second-generation antipsychotics). Thus, we observed that the use of lower dosages of lithium resulted in significantly lower exposure to second-generation antipsychotics.

The average lithium blood levels for those taking lithium were <0.6 mEq/L, below the range typically considered to be therapeutic for acute phase therapy, which is consistent with the design of the study. However, lithium blood levels were relatively consistent across the 6 months of treatment, although the protocol permitted upward titration of lithium doses if clinically indicated. This indicates that study physicians may have become “locked in” to the lower dosage strategy and did not try to give maximally tolerated doses at optimal levels. Yet additional analyses found no relationship between improvement in MADRS or YMRS scores based on categories of lithium blood levels in the first 12 weeks (<0.4 mEq/L [N=47], 0.4–0.9 mEq/L [N=67], and >0.9 mEq/L [N=1]). The findings were similar for those in the low and higher lithium level categories at 24 weeks. Thus, participants who received higher dosages of lithium did not have superior outcomes, but results could be confounded by physicians increasing lithium dosages in response to more severe illness. In any event, our study was not designed to provide any information about the utility of higher lithium dosages in combination with OPT.

We could interpret the results of LiTMUS as simple confirmation that higher dosages and blood levels of lithium plus OPT would be required for efficacy beyond OPT alone. The classic study of lithium blood levels by Gelenberg et al. (

35) suggested that levels >0.8 mmol/L are required for maintenance treatment. In that study, bipolar patients who were stable for 2 months while taking lithium (with blood levels between 0.6 and 1.0 mmol/L) were then randomly assigned to either lower levels (0.4–0.6 mmol/L) or higher levels (0.8–1.0 mmol/L). Those patients assigned to lower levels were 2.6 times more likely to have a mood episode. A reanalysis of these data found, however, that the relationship between blood levels and outcome was more complicated (

36). Those patients who were taking low levels of lithium during the pre-randomization phase and were then randomly selected to continue with low levels stayed well. In contrast, those patients who took higher levels during the pre-randomization phase and were then assigned to low levels had higher rates of relapse relative to those who continued at higher levels. If anything, this reanalysis suggests that at least a subpopulation of bipolar patients could get well and stay well on lower blood levels of lithium monotherapy. Note that the low lithium blood levels in LiTMUS were not used as monotherapy or maintenance, but instead as part of an acute strategy of treatment in addition to active OPT. Results from LiTMUS revealed no additional symptomatic benefit with low to moderate dosages of lithium beyond OPT.

Other, more recent effectiveness studies of lithium have yielded findings consistent with the results of LiTMUS. Researchers in the BALANCE (Bipolar Affective Disorder: Lithium/Anticonvulsant Evaluation) study (

37) compared maintenance therapy with lithium alone, divalproex alone, or combination treatment with both drugs for up to 2 years for patients who were initially stabilized with the combination. While the combination was statistically superior to divalproex alone, the overall outcomes were unfavorable, with relapse rates across the groups exceeding 50%. Similarly, researchers in another effectiveness study (

38) compared lithium to lamotrigine maintenance after initial stabilization with any medication and found that only a minority of patients sustained stabilization, and most of those who stabilized experienced a clinically relevant event within the first 6 months of treatment assignment.

In our study, several factors could have decreased the probability of finding a difference between the groups if such a difference did exist, such as heterogeneity of the sample and the wide range of treatments permitted in OPT. It is plausible that a study focused on a narrower subgroup (e.g., rapid cycling bipolar I patients with manic or hypomanic symptoms) or using a single other medication (e.g., divalproex or a second-generation antipsychotic) could have yielded different results. With only about one-quarter of the sample reaching remission after 6 months of guideline-concordant treatment, it seems more likely that the group was, at best, partially responsive to treatment, indicating that symptoms of bipolar disorder can persist despite evidence-based pharmacotherapy.

Other potential study limitations include open treatment, which could have influenced physician prescribing behavior, with potential biases for and against lithium. Although the broad inclusion criteria and limited exclusion criteria enhanced generalizability, the burden of comorbid conditions could have limited responsiveness to treatment. The effectiveness of lithium could also have been compromised by persistent low dosages with the goal of enhanced tolerability, even in the context of insufficient response to lithium plus OPT. It is also possible, given that less than half of the participants were taking lithium in low dosages (blood levels, <0.4 mEq/L), that our study did not have enough power to detect clinically meaningful differences. Another potential confounding factor is that the lithium-plus-OPT group had more hypomanic or manic episodes in the preceding year compared with the OPT-only group. Additional analyses of the complex relationship between changes in lithium dosage (or absence of lithium therapy), adverse effects, and effectiveness are warranted.

In summary, we found no differences in symptomatic outcomes between the lithium-plus-OPT and OPT-only groups, although the lithium-plus-OPT group did receive significantly less exposure to second-generation antipsychotics. In the context of concerns about long-term adverse effects of second-generation antipsychotics, including metabolic syndrome and tardive dyskinesia (

39), as well as a reappraisal of the benefit-to-risk ratio of lithium that suggests that the short- and long-term toxicity of lithium may have been overestimated (

40), clinicians can use the results of this study to reconsider lithium for their bipolar patients. Given the modest clinical improvements overall, the LiTMUS findings highlight the persistent and chronic nature of bipolar disorder as well as the magnitude of unmet needs in its treatment.