In late life, bipolar disorder is associated with high utilization of mental health and other medical services (

1), persisting disability (

2), increased mortality (

3), and increased risk for suicide (

4) and dementia (

5). Despite the increasing number of older adults with bipolar disorder, evidence that can guide their treatment is strikingly limited. Physiological changes and comorbid diseases increase vulnerability to adverse effects of medication in this population (

6,

7). The sparse literature on treatment outcomes for late-life mania is inconsistent (

6,

8–

10).

Both lithium and divalproex are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for the treatment of bipolar disorder (

11), and they are the traditional mood stabilizers most commonly prescribed for older patients. Although some analyses of geriatric patients in open studies have been published, most information to guide the use of these medications has been extrapolated from studies of younger adults with bipolar disorder or retrospective analyses of a limited number of older patients (

12). Lithium has the strongest evidence supporting both its acute and long-term efficacy in mid-life adults with bipolar disorder. Uncontrolled data suggest that lithium can also be efficacious in bipolar disorder in late life (

12), for which it remains commonly prescribed despite some decline in new prescriptions (

13). However, many older patients do not tolerate lithium at the concentrations recommended for younger patients (

14), and concerns about the drug’s tolerability lead to use of either unproven lower concentrations (

15) or alternative medications, such as divalproex.

Divalproex is reportedly well tolerated by nondemented older patients, including those with neurological and medical disorders, and case series suggest that it can be effective for the treatment of late-life mania (

12). Its use in older patients has been increasing (

13) despite the absence of randomized controlled trials comparing its tolerability and efficacy with those of lithium or other agents in this population. Our reviews of open treatment data in older patients (

12) and related research in younger patients (

11) suggested that divalproex was more likely than lithium to cause sedation, but less likely to cause tremor and other side effects.

Optimal serum concentrations of lithium or valproate for treatment of older patients with bipolar disorder are not established, and open treatment has involved a range of serum concentrations. In older patients, tolerability can limit dosing and thereby efficacy. Our review (

12) indicated that relatively low concentrations of lithium (0.30–0.79 mEq/L) may be less effective than higher concentrations (0.80 mEq/L) or than usual therapeutic levels of valproate (72–84 μg/mL) (

15). Nonetheless, in one case series, geriatric mania was treated successfully with lithium levels of 0.5–0.8 mEq/L (

16). Thus, the relative tolerability and efficacy of lithium and divalproex remain unknown in older patients with bipolar disorder.

We conducted a randomized, double-blind, concentration-controlled study to compare the acute tolerability and efficacy of lithium and divalproex in older adults with bipolar I disorder presenting with mania. Based on the literature, we hypothesized that patients treated with divalproex would experience greater sedation, but we expected that patients treated with lithium would experience more tremor and other adverse effects (

14). Thus, we expected that divalproex would be better tolerated overall, and we hypothesized that a higher proportion of patients treated with divalproex would achieve a potentially beneficial target serum concentration. As a result, we predicted that divalproex would be more efficacious than lithium.

Method

GERI-BD (Acute Pharmacotherapy of Late-Life Mania) was a 9-week randomized double-blind parallel-group trial. Participants were older patients with bipolar I disorder presenting with mania or hypomania. Dosing was guided by serum drug concentration. Participants with inadequate response after 3 weeks received open adjunctive treatment with risperidone.

Setting and Participants

We recruited participants at six academic centers, from both inpatient and ambulatory services. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants, as required by the local institutional review boards, with mental health professionals who were not part of the research team assessing and documenting the participants’ capacity to provide consent. When potential participants did not have capacity, consent was provided by a substitute decision maker.

The inclusion criteria specified that participants had to be at least 60 years of age; meet DSM-IV criteria for bipolar I disorder with a current manic, mixed, or hypomanic episode based on the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID) (

17); and have a score ≥18 on the Young Mania Rating Scale (YMRS) (

18). Patients were excluded if they had schizophrenia, schizoaffective disorder, or delusional disorder; a diagnosis of delirium or dementia or other brain degenerative diseases; an unstable medical condition; a mood disorder due to a general medical condition (e.g., recent stroke, hyperthyroidism, porphyria, HIV infection, connective tissue diseases) or to a substance (e.g., steroids,

l-dopa); active substance dependence or other substance-related safety issues; rapid cycling; sensory impairment preventing participation in research assessments; a high risk for suicide (in ambulatory patients); any contraindication to lithium or divalproex; a history of intolerance of lithium (at a concentration <1.0 mEq/L), divalproex (with a valproate concentration <100 μg/mL), lorazepam, or risperidone; or a requirement for other immediate pharmacological intervention. Participants who were unable to communicate in English or whose current episode had failed to respond to at least 4 weeks of treatment with lithium (at a concentration ≥0.4 mEq/L) or divalproex (at a valproate concentration ≥40 μg/mL) were also excluded.

Assessments

Antidepressants and other nonstudy medications were tapered off to ascertain whether manic symptoms would resolve with their discontinuation. Baseline demographic information was recorded, and baseline assessments included the YMRS, the SCID, the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (

19), the Udvalg for Kliniske Undersøgelser (UKU) Side Effect Rating Scale (

20), a physical examination, and laboratory studies.

Randomization

Eligible patients were randomly assigned, under double-blind conditions and on a 1:1 basis, to receive lithium or divalproex. Permuted-block randomization employed block sizes ranging randomly from four to eight consecutive patients by site. Participants received monotherapy with lithium or divalproex in over-encapsulated pills given twice daily.

Intervention

Dosages were started at 300 mg/day for lithium and 500 mg/day for divalproex and were titrated to achieve target serum concentrations of 0.80–0.99 mEq/L of lithium (acceptable range: 0.40–0.99 mEq/L) or 80–99 μg/mL of valproate (acceptable range: 40–99 μg/mL). Trough concentrations were determined 10–14 hours after the last dose on treatment days 4, 9, 15, and 21, at weeks 6 and 9, and more frequently if indicated. Concentrations were reported to an unblinded clinician who created an equivalent “dummy concentration” for the other drug (e.g., 0.58 mEq/L and 58 μg/mL); both concentrations were then provided to the blinded psychiatrist. Titration to the target ranges was carried out regardless of mood improvement. Dosing was reduced if serum concentrations exceeded the target range, if significant side effects occurred (including tremor interfering with self-care, ataxic gait, excessive sedation, or heart rate <50), or if the blinded research psychiatrist had other concerns. The research medication was discontinued and the participant was terminated from the study if these side effects persisted despite a dosage reduction or if any of the following occurred and persisted: inability to tolerate at least 0.40 mEq/L of lithium or 40 μg/mL of valproate; delirium; a platelet count below 80,000; elevation in SGOT, SGPT, or amylase twofold or more above the upper limit of normal; or diabetes insipidus.

Standard behavioral interventions were used for all participants, including provision of an educational brochure, reduction of excess social stimuli, and use of seclusion and restraint for inpatients if needed for safety. During the first 3 weeks of treatment, lorazepam was used at a maximum dosage of 3 mg/day when anxiety, agitation, or insomnia was significant and not responsive to behavioral interventions. For participants who did not respond to behavioral intervention and lorazepam, oral risperidone (

21) rescue (at doses of 0.5–1 mg) was used up to twice a day for up to 3 days in any week. Participants who required dosages higher than these were terminated from the study. After 3 weeks of treatment, risperidone, up to 4 mg/day, was used for an inadequate response to lithium or divalproex, defined as a YMRS score ≥16, and lorazepam was tapered off. Patients not receiving adjunctive risperidone could receive lorazepam at 0.5–1.0 mg/day for persistent anxiety or insomnia.

Other psychotropic medications were not allowed, but medications for comorbid physical conditions were continued. When nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents or thiazide diuretics were required, mood stabilizer dosages were adjusted based on serum concentrations.

Participants could also be terminated from the study by clinician recommendation or nonadherence to study procedures and medications or if they withdrew consent, had a serious adverse event, had an increase in YMRS score >40% above baseline, or developed major depression and had a score ≥18 on the 21-item Hamilton Depression Rating Scale (

22) on two successive assessments or needed antidepressant treatment.

The conduct of the study was monitored by an operations committee and by a National Institute of Mental Health data safety monitoring board. Data management was performed at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Statistical Analysis of Tolerability and Efficacy

The primary clinical tolerability measure was the sleepiness/sedation item of the UKU Side Effect Rating Scale; the primary pharmacologic tolerability measure was the proportion of participants in each group who achieved serum concentrations within the target range; and the primary efficacy measure was the change in YMRS score. The analysis for primary outcome measures was based on the intent-to-treat principle with a generalized linear mixed model for continuous and binary or multinomial longitudinal response. A patient-level random intercept was assumed, and linear (time) and time-by-treatment factors were included in the model. Higher polynomial orders of the time term (quadratic [time2], cubic [time3], or quartic [time4]) and their corresponding interactions with treatment were explored and retained in the model based on best model fit and visual inspection of observed and predicted values. Site was included as a covariate in the model. In addition, site-by-time and site-by-time-by-treatment interactions were investigated and were included if they were significant and improved model fit. Individual UKU Side Effect Rating Scale item scores (range: 0–3) were analyzed as both continuous and ordinal outcomes in the linear and the ordinal logistic mixed model, respectively; the conclusions were similar, and the results from the continuous outcome analysis are presented. A binary UKU Side Effect Rating Scale outcome was also defined as an increase of 2 points from baseline or reaching 3; it was analyzed in a generalized linear mixed model; conclusions were similar to continuous UKU Side Effect Rating Scale scores except for tremor, which had few events and did not converge.

Post hoc tests for treatment comparisons were conducted for each outcome on the chosen mixed model to test group difference at weeks 3 and 9. Corresponding estimates of treatment difference, standardized effect size (Cohen’s d), confidence intervals, and p values are also reported. To control for type I errors due to multiple comparisons, the p value corresponding to the F test of the highest interaction term in a mixed model was adjusted using the Holm step-down procedure for controlling family-wise error rate. Alphas were adjusted using the Holm procedure, and 97.5% confidence intervals (two-tailed) were constructed for the two post hoc tests for each outcome. The effect size (Cohen’s d) for treatment difference was based on the mixed-model estimated least-square means and standard deviations (raw) at weeks 3 and 9.

To explore whether between-group differences in treatment outcomes were associated with whether or not concurrent serum concentrations were within the target range, a linear mixed model as described above was used with additional fixed effects for target and target-by-time, target-by-treatment, and target-by-time-by-treatment interactions.

Using similar linear mixed models, two treatment moderators (older age and mixed-manic state) were tested using additional fixed effects for moderator and moderator-by-time, moderator-by-treatment, and moderator-by-time-by-treatment interactions. A significant three-way interaction would indicate the effect of a moderator.

Using a two-tailed 2.5% level of significance for the primary hypotheses, we calculated a priori that a sample size of 207 would provide 82% power for minimal differences of 20%, that is, a difference of 20% in the rates of sedation or treatment response for the tolerability and efficacy hypotheses, respectively. This estimate of power was conservative, as multiple visits per patient were not taken into consideration because of lack of within-subject correlation information.

Results

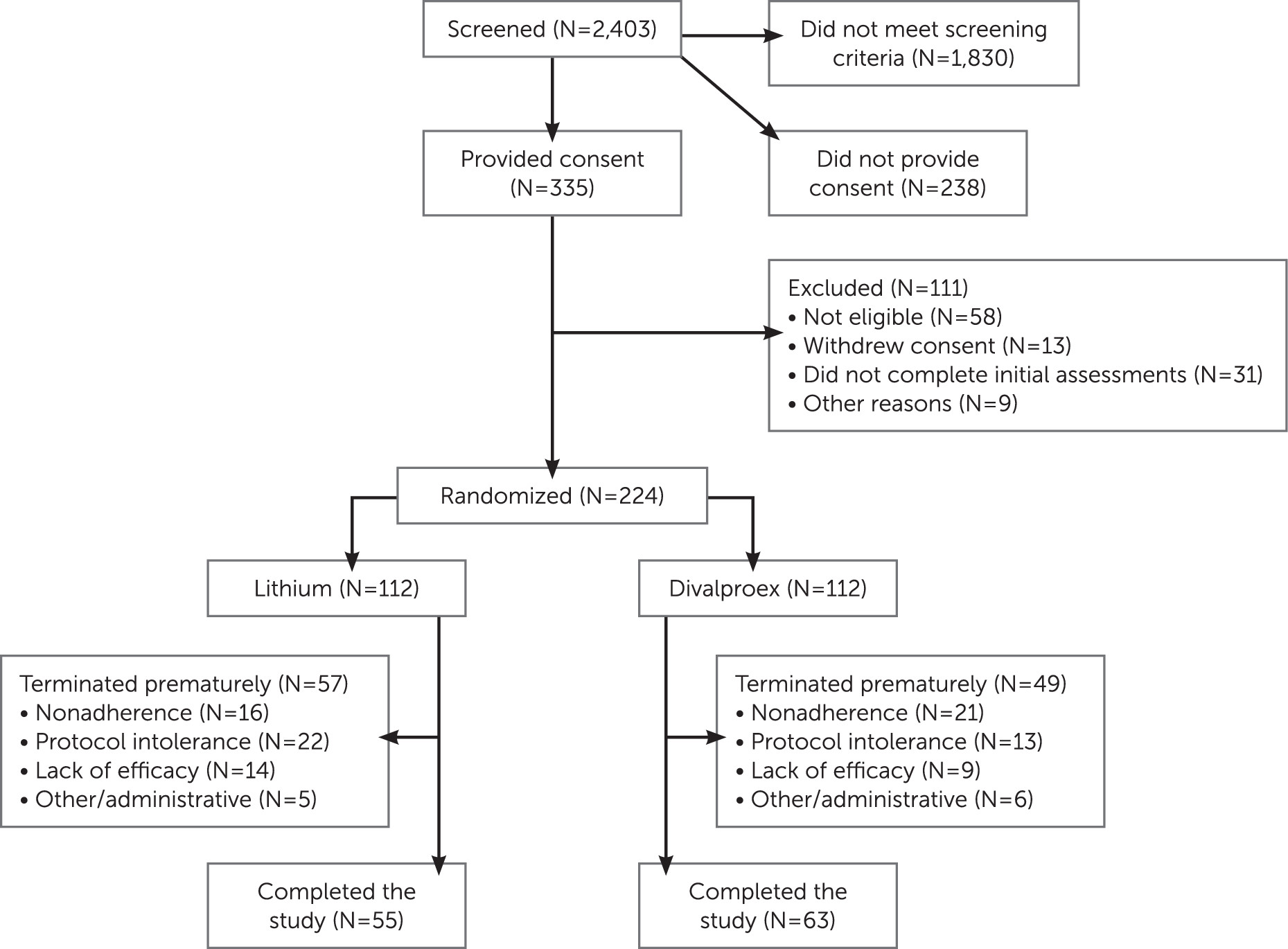

The flow of participants through the study is outlined in

Figure 1. The most frequent reasons for exclusion from the study were a low YMRS score or the presence of a major depressive episode. The demographic and clinical characteristics of the 224 randomized participants did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups (

Table 1). Age at onset of first manic episode ranged from 9 years to 82 years.

Attrition

The attrition rates in the lithium and divalproex groups were 14% and 18%, respectively, at week 3 and 51% and 44% at week 9 (not significantly different at either time point). In a longitudinal generalized linear mixed-effects model of attrition, the slope did not differ significantly between treatment groups. Time to attrition also did not differ significantly between the treatment groups based on a log-rank test of survival curves (see Figure S1 in the

data supplement that accompanies the online edition of this article). The distribution of reasons for attrition did not differ significantly between groups (refusal/nonadherence: 28.1% and 42.9% in the lithium and divalproex groups, respectively; inability to tolerate the protocol, 38.6% and 26.5%; clinical worsening/lack of efficacy, 24.6% and 18.4%; and administrative/other, 8.8% and 12.2%) (see

Figure 1).

In exploratory analyses, rates of 9-week study completion did not differ between treatment groups based on age or medical burden as measured by the Cumulative Illness Rating Scale–Geriatric (

23) when analyzed in two separate logistic regression models with 9-week study completion as outcome.

Rescue and Adjunctive Medications

The odds of needing rescue lorazepam or adjunctive risperidone did not differ significantly between groups (60.7% and 50.9% in the lithium and divalproex groups, respectively; odds ratio=1.49; 95% CI=0.88, 2.5). Similarly, the use of adjunctive risperidone (i.e., consistent use of up to 4 mg/day after week 3) did not differ significantly between groups (17.0% and 14.3%, respectively; odds ratio=1.23; 95% CI=0.59, 2.5). However, the two groups differed in daily use of lorazepam after day 28 (9.8% and 19.6% in the lithium and divalproex groups, respectively; χ2=4.3, df=1, p=0.038).

Tolerability

Side effect ratings (Table 2).

There was no significant difference between the treatment groups in the primary measure, change in sleepiness/sedation. Planned secondary measures were tremor, weight gain, and nausea/vomiting. For tremor, the treatment-by-time interaction fell just short of significance at week 9, with the divalproex group having lower scores than the lithium group (Cohen’s d=−0.30, 97.5% CI=−0.93, −0.10) but not at week 3 (d=−0.17, 97.5% CI=−0.55, 0.11). For weight gain, the treatment-by-time interaction was significant, but since there was no treatment difference at weeks 3 and 9, the clinical significance of that interaction is unclear. For nausea/vomiting, the treatment-by-time interaction was not significant.

Target concentrations.

The mean maximum daily doses and serum concentrations were 780 mg (SD=315) and 0.76 mEq/L (SD=0.35) for the lithium group and 1,200 mg (SD=550) and 74 μg/mL (SD=21) for the divalproex group. Similar proportions of participants achieved target concentrations in the two groups. In the intent-to-treat linear mixed model at days 4, 9, 15 and weeks 3, 6, and 9, the treatment-by-time interaction was not significant, and post hoc tests showed comparable proportions of participants achieving target concentrations at week 3 (35.1% and 32.6% in the lithium and divalproex groups, respectively) and week 9 (57.1% and 56.3%, respectively).

Efficacy

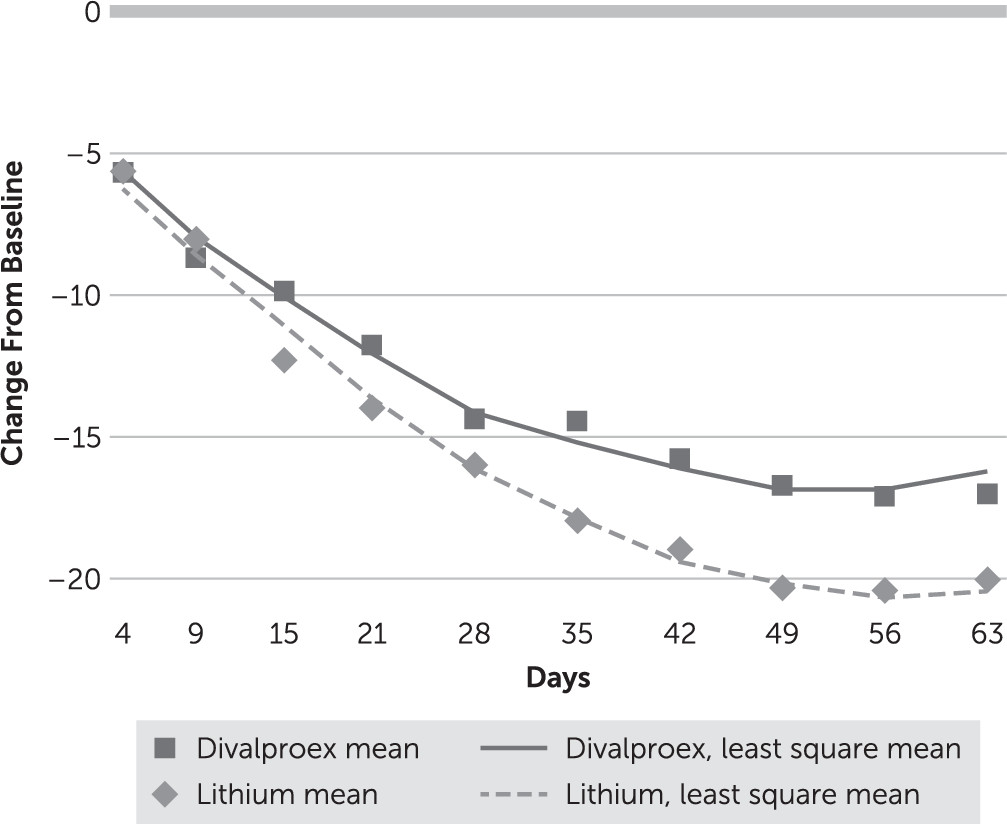

In the intent-to-treat linear mixed model of change in YMRS score, there was a significant treatment-by-time interaction (F=16.87, df=1, 1382, p<0.001). YMRS score decreased significantly from baseline (day 0) in both treatment groups, but the decrease was larger in the lithium group than in the divalproex group (

Figure 2). A post hoc test showed a difference in YMRS scores of 1.57 (d=0.18, 97.5% CI=−0.05, 0.60) at week 3 and 3.90 at week 9 (d=0.54, 97.5% CI=0.32, 1.15) in favor of lithium. YMRS course over time depended on baseline YMRS: among participants with a baseline YMRS score >30, those in the lithium group had a greater reduction in score than those in the divalproex group (time-by-treatment-by-YMRS score >30: F=17.76, df=3, 1379, p<0.001), but there was no difference between groups among participants with a day 0 YMRS score <30. Among all study participants, the cumulative rates of response (defined as a reduction of at least 50% in YMRS score) at week 3 were 62.5% and 57.1% in the lithium and divalproex groups, respectively (adjusted odds ratio=0.78, p=0.37), and at week 9, 78.6% and 73.2% (adjusted odds ratio=0.72, p=0.31). The cumulative rates of remission (defined as a YMRS score ≤9) at week 3 were 45.5% and 43.8% in the lithium and divalproex groups, respectively (adjusted odds ratio=0.91, p=0.74), and at week 9, 69.6% and 63.4%, respectively (adjusted odds ratio=0.73, p=0.29).

In an exploratory analysis, the course of YMRS score reduction differed between the two treatment groups based on whether or not serum concentrations were at target (target-by-time-by-treatment interaction: F=5.80, df=1, 1379, p=0.016). Below-target concentrations in the lithium group were associated with the fastest symptomatic reduction (see Figure S2 in the online data supplement). In another exploratory analysis, older age (≥70 years compared with 60–69 years) and mixed-manic state (N=52) compared with manic/hypomanic state (N=144) were not associated with any significant difference in the course of treatment effect.

The MADRS depression scores were analyzed as a secondary efficacy measure. Scores were relatively low at baseline, and they decreased during treatment; there was no significant difference between the groups.

Discussion

This is, to our knowledge, the first randomized controlled trial of the treatment of late-life mania. Our principal finding is that the overall tolerability and efficacy of lithium and divalproex were comparable in older patients. Contrary to our hypothesis, sedation and the proportion of participants who achieved target serum concentrations did not differ significantly between the two treatment groups. Overall attrition did not differ significantly between groups, and there were no significant differences in other secondary clinical tolerability measures.

The effect of lithium on ratings of mania severity was statistically larger, with a small effect size at week 3 and a moderate effect size at week 9. The higher use of lorazepam in the divalproex group is consistent with a greater efficacy of lithium. However, rates of response and remission did not differ between the two treatment groups: they were substantial, and less than 20% of participants required an adjunctive antipsychotic, despite the fact that 34% presented with psychotic features and 50% were initially inpatients. Finally, neither mood stabilizer was associated with increased ratings for depressive symptoms.

Our findings need to be considered in the context of the literature. First, even though the attrition rates in this study were substantial, they were similar to or lower than those in studies of younger patients with mania (

24). Second, our findings are consistent with the results of analyses of subgroups of older participants in recent adult studies. The European Mania in Bipolar Longitudinal Evaluation of Medication (EMBLEM) study reported benefit from mood stabilizers in a geriatric subgroup (

10), and in the Systematic Treatment Enhancement Program for Bipolar Disorder (STEP-BD) study, lithium monotherapy was associated with remission in 42% of older participants (

6). Third, our finding of higher efficacy for lithium than for divalproex is congruent with findings in the Bipolar Affective Disorder: Lithium/Anticonvulsant Evaluation (BALANCE) study of relapse prevention in bipolar I disorder (

25): in a mixed-age sample of remitted patients randomly assigned to open continuation treatment with lithium, divalproex, or the combination for up to 24 months, lithium was associated with statistically lower relapse rates, although the effect was small. Finally, we found rates of response or remission similar to the rates reported in younger patients with bipolar disorder treated with lithium or divalproex even though we used lower dosages and lower serum level targets. For instance, a 3-week double-blind randomized controlled trial of lithium and divalproex monotherapy (

11) in a sample of patients with a mean age of 41 years reported comparable outcomes in the two groups when using “conventional” concentration targets (0.80–1.20 mEq/L for lithium and 80–120 μg/mL for valproate). In younger patients, these concentrations are usually well tolerated and associated with favorable outcomes (

26,

27).

The findings concerning our primary hypotheses in this study must be interpreted in light of potential limitations. First, although the inclusion criteria were intended to be as broad as safely possible, a relatively large number of patients were excluded. Second, in the absence of a placebo group, it is possible that the observed improvements were due to factors other than the study medications; however, this is unlikely given the low rate of response to placebo in a comparative trial in a mixed-age sample of patients with bipolar disorder (

11). Finally, this trial lasted only 9 weeks, so it does not provide data on the long-term tolerability and efficacy of lithium or divalproex in older persons with bipolar disorder.

The exploratory hypothesis testing we report here presents examples of the important potential use of study data in further analyses. These included examination of mediators of outcomes and of potential moderators, such as illness course variables.

Our main findings, if confirmed, have implications for geriatric practice and investigation. Treatment with lithium or divalproex with conservative serum concentration targets, combined with limited use of rescue and adjunctive medications, was tolerated by older patients with mania, and it benefited a substantial proportion of them. These results suggest that treatment guidelines for older persons with bipolar disorder should emphasize greater use of lithium and less exposure to antipsychotics. This approach may be particularly appropriate in older patients, since lithium may have neuroprotective (

28) and antisuicide (

29) effects, while antipsychotics can be associated with serious adverse effects, including premature mortality (

30).