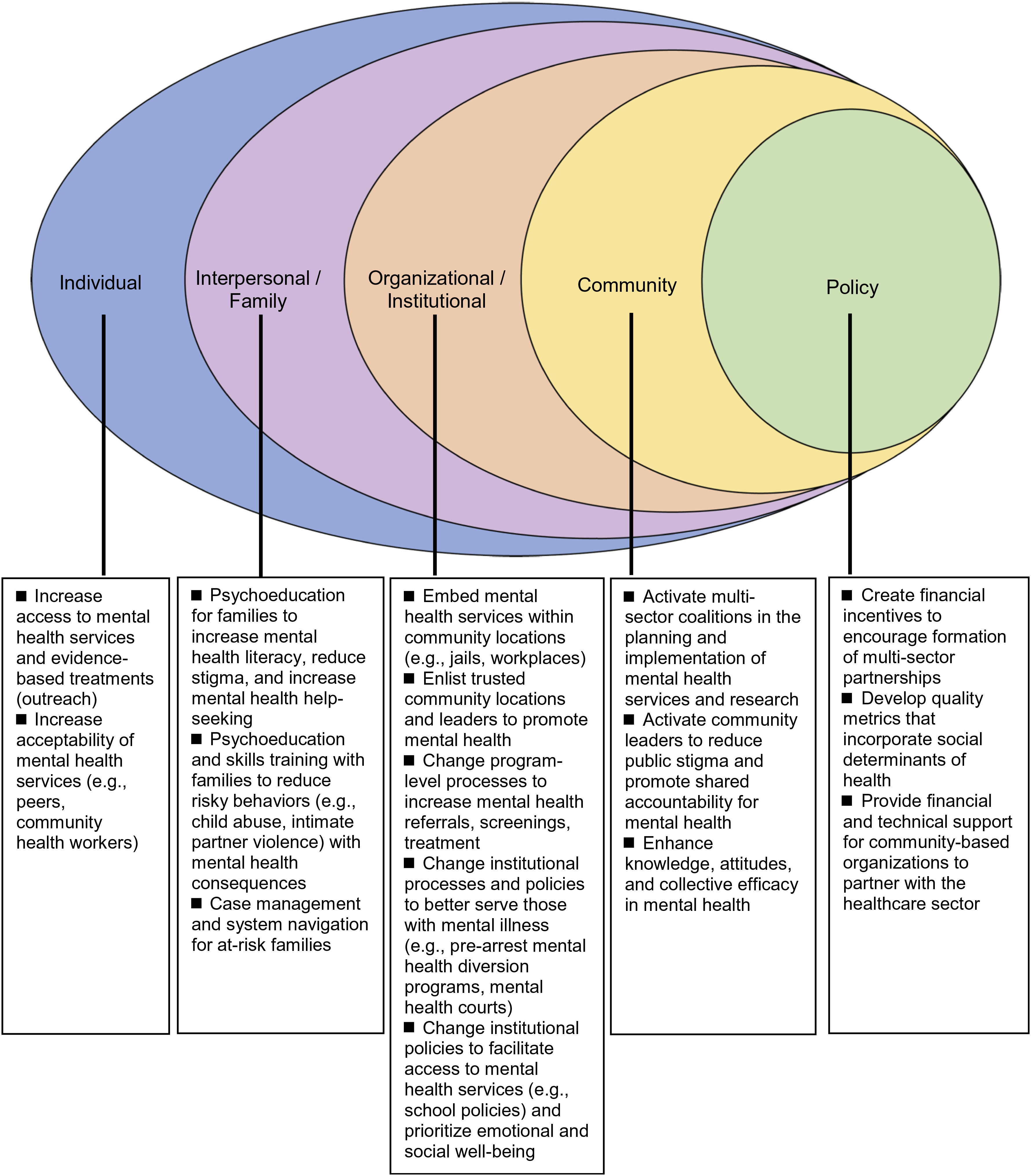

Actions of community interventions by social-ecological level.

The community interventions above (Appendix A), drawn from a larger selection (Appendix B), highlight the successes and promise of these interventions to promote mental health and broader outcomes at all social-ecological levels: individual, interpersonal/family, organizational/institutional, community, and policy (

3). Community involvement is represented in varied ways in the form of individuals (lay health workers), settings (churches, schools), leaders (community-based participatory research), and multi-sector coalitions (

35,

37,

38,

39,

85,

86–

90,

91,

103). Many studies examined the interplay among mental health services, social and structural determinants, and mental health outcomes. Some explicitly assessed social outcomes like intimate partner violence, housing retention, academic performance, parent-child interactions, “societal healing,” and other contributors to mental and social well-being (

67,

92,

94,

111).

Figure 1 summarizes the actions of community interventions by social-ecological level to promote mental health and social well-being. We found that most interventions reviewed promoted mental health at the individual level. LHW interventions extend access and increase acceptability of mental health services by leveraging trusted relationships. For example, Patel et al. demonstrated the successful delivery of behavioral activation for depression by LHWs through relatively brief training to a population with significant barriers to healthcare access (

91). Some studies adapted evidence-based models (e.g., Forensic Assertive Community Treatment) to deliver treatments in non-traditional locations, such as jails, churches, and senior centers (

77). Many individual-level interventions also simultaneously acted at the organizational/institutional level. In the successful RCT of Head Start REDI, teachers were provided with professional development and mentoring to deliver an enriched curriculum (

60).

A second group of interventions intervened at the interpersonal level (e.g., parent and family interventions). The effective child abuse prevention program in South Africa focused on the parent-child dyad through individual and joint sessions (

92). Additionally, a strength of this intervention was its delivery by local child care workers. A third group of interventions functioned at the organizational/institutional level by enhancing the processes by which non-healthcare programs serve those with mental illness. These interventions enlisted non-healthcare entities and trusted community leaders to be active in mental healthcare, such as providing a depression screening intervention in churches (

38,

39). Several successful school-based interventions operated at the organizational level, such as Warschburger and Zitzmann’s universal school-based prevention program for eating disorders in Germany and other whole school approaches (

111,

112).

We found only a small number of studies that intervened at the level of whole communities. Most interventions reviewed here included one non-healthcare sector collaborator as opposed to collaborating with communities more broadly. Examples of community-level interventions include CPIC, which involved 95 organizations in 5 sectors to develop community-wide plans for managing depression, and CTC that supports communities to develop multi-sector coalitions to prevent youth substance use, violence, and delinquency (

35,

103). Other studies acted at the community level by directly providing or influencing resources on a large scale, through cash/food transfers or land revitalization efforts (

94,

105,

106,

107,

108,

109,

110).

A fifth group of interventions are health and public policies. Policies that promote mental health equity are beyond the scope of this review but are detailed in our recent review on this topic (

113). Policies as varied as mental health insurance parity, assisted outpatient treatment statutes, quality metrics for social determinants of health, value-based payment reforms, and the integration of funds and services for health and social care have the potential to improve access to treatment and improve outcomes (

114–

117,

118,

119–

121). Policies facilitating multi-sector health collaborations include the Accountable Health Communities model, California’s Whole Person Care pilots, the Certified Community Behavioral Health Clinics Demonstration Program, New York’s Home and Community-based Services, the UK’s Social Impact Bonds Trailblazers, and the National Health Service England’s social prescribing teams (

122–

127). Nation-level efforts to promote shared values for mental and social well-being are Australia’s mental health anti-stigma campaign, the US National Prevention Strategy’s focus on emotional well-being, and the UK’s Campaign to End Loneliness (

128–

130). Thrive NYC is an example of large-scale action to promote mental health at the civic level, with a budget of $850 million and 54 initiatives across all public agencies and departments, with special emphases on community partnerships and prevention (

131,

132).

Ethical considerations.

Ethical considerations are of importance to many community interventions given the focus on marginalized and under-resourced populations (

24,

133). Research on interventions for at-risk individuals with stigmatized conditions (e.g., incarceration, homelessness) should build trust with participants and recognize structural forces that place them at higher risk for these conditions (e.g., discriminatory policing and housing policies), to avoid inadvertently worsening stigma. Involving community stakeholders in equitable arrangements for interventions and research requires the necessary time and processes to develop effective partnerships. The expertise of community leaders and other stakeholders can be integrated equitably with that of researchers with trust, respect, and two-way knowledge exchange (

134,

135). Community-based organizations, social services, and healthcare agencies also have different funding streams and incentives. Efforts to sustain interventions should include a focus on funding and other enabling infrastructures (e.g., training, technology) for community groups to participate in intervention-related activities.