Introduction

Depressive disorders are a leading cause of disability and emotional, physical, and economic burden (

1). Antidepressants are the first-line pharmacological treatment option for major depressive disorder, but inadequate response is common, with more than half of patients not achieving remission from their first antidepressant trial (

2). Clinical approaches to incomplete response include switching to another antidepressant followed by various augmentation strategies (

3,

4). Although not widely supported by treatment guidelines, augmentation with concomitant antidepressants is common in US practice

4 and has some empirical support (

5–

8). Augmentation with newer antipsychotics was at the time of the study the only treatment option approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (aripiprazole, quetiapine, olanzapine/fluoxetine). Randomized controlled trials of augmentation with newer antipsychotics have demonstrated efficacy in reducing observer-rated depressive symptoms (

9,

10), but have been criticized for their methodology and lack of demonstration of benefit on quality of life and functional outcomes (

11,

12).

Further, newer antipsychotics have well characterized serious adverse effects, including rapid weight gain, diabetes, and tardive dyskinesia (

13,

14). Newer antipsychotics have also been associated with increased mortality, most notably a

>50% increased mortality risk in older adults with dementia (

15,

16). However, due to the restricted inclusion criteria and limited sample sizes of RCTs for newer antipsychotic augmentation (

11,

17–

19), these trials are uninformative with regard to a potential mortality risk for augmentation with newer antipsychotics for depression in clinical practice.

The safety of newer antipsychotic augmentation for depression should be viewed in the context of limited therapeutic benefits (

11,

18) and widespread clinical use (

20–

23). In the US, approximately 2 million office-based medical visits per year for depression include prescriptions for newer antipsychotics (

20). Furthermore, most patients who initiate newer antipsychotic treatment for nonpsychotic depression either do not have a prior adequate trial with antidepressants or have initiated the newer antipsychotic without a concomitant antidepressant (

21). These prescribing practices raise concern that newer antipsychotic initiation for depression may sometimes be premature or clinically inappropriate.

The uncertain safety profile of augmentation with newer antipsychotics for depression complicates clinical decisions concerning their appropriate role in treatment for patients who do not have an adequate response to antidepressant monotherapy. This study aimed to estimate the real-world mortality risk of newer antipsychotics in non-elderly adults with depression and an incomplete response to antidepressant monotherapy.

Results

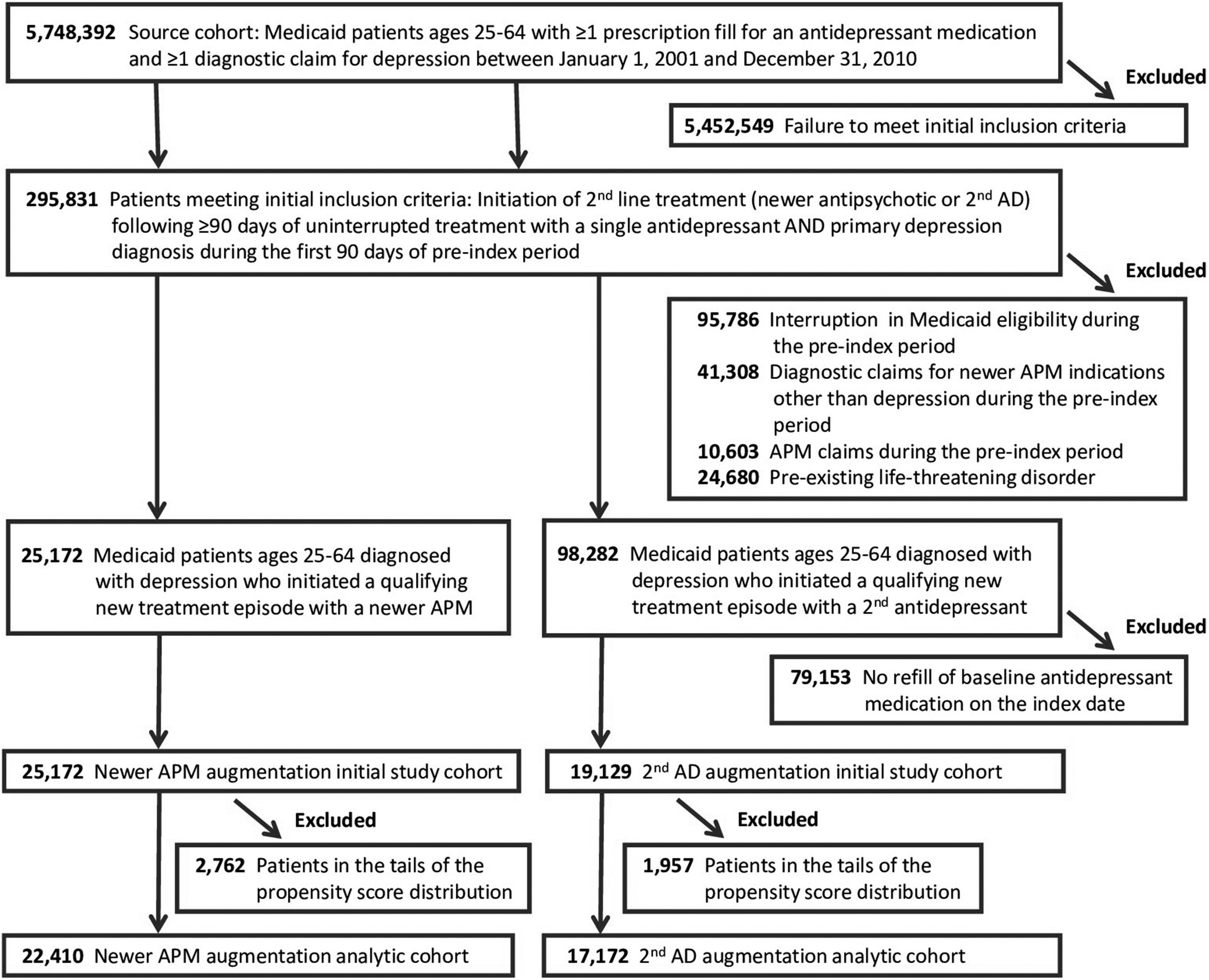

The initial study cohort included 44,301 patients: 25,172 initiators of antipsychotic augmentation and 19,129 initiators of augmentation with a second antidepressant (

Fig 1). Baseline antidepressants were SSRIs (56%), atypical antidepressants (20%), SNRIs (18%), and other antidepressants (6%), with minimal differences between treatment cohorts (eTable 1, S1

https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0239206.g001 Appendix). In the antipsychotic augmentation cohort, quetiapine was the most commonly prescribed newer antipsychotic (40%), followed by risperidone (21%), aripiprazole (17%), and olanzapine (16%) (eTable 4, S1 Appendix). The remaining newer antipsychotics together made up the remaining 6%. The median chlorpromazine equivalent starting daily dose for all newer antipsychotics combined was 68 mg. During follow-up, the median combined chlorpromazine equivalent dose increased to 100 mg. Starting and final doses for commonly used individual antipsychotics (actual mg as well as mg chlorpromazine equivalents) are shown in eTable 4 (S1 Appendix). Add-on antidepressants in the comparator cohort were most commonly atypical antidepressants (59%), followed by SSRIs (21%), other antidepressants (11%), and SNRIs (9%; eTable 1, S1 Appendix).

Patients in the initial cohort were on average 44 years old, predominantly female (78%), non-Hispanic white (70%), and eligible for Medicaid due to disability (64%). The most prevalent comorbid baseline diagnoses were anxiety (25%), hypertension (23%), hyperlipidemia (15%), and diabetes (14%) (

Table 1 and eTable 3, S1 Appendix). Over the 180-day baseline period, study patients averaged 9.2 outpatient visits for depression and 15.5 non-mental health outpatient visits. Seventy-five percent had prescription claims for psychotropic drugs other than antidepressants or antipsychotics, most commonly anxiolytics/hypnotics (64%) and mood stabilizers (32%). The two treatment groups were generally comparable in their baseline characteristics but showed meaningful differences as indicated by standardized differences of

>10% for several potential confounding variables (

Table 1 and eTable 3, S1 Appendix). After propensity score trimming and inverse probability of treatment weighting, group differences were markedly diminished (

Table 1). The resulting analytic study cohort included 39,582 patients (78.5% female, mean age 44.5 years), 22,410 initiators of augmentation with a newer antipsychotic, and 17,172 initiators of a second antidepressant (

Fig 1). Characteristics of individuals excluded from the analytic cohort due to propensity score trimming are shown in eTable 3 (S1 Appendix).

In the analytic cohort, initiators of newer antipsychotics had 105 deaths during 7,601 personyears of follow-up (138.1 per 10,000 person-years) (

Table 2). Initiators of antidepressant augmentation had 48 deaths during 5,727 person-years of follow-up (83.8 per 10,000 person-years). Discontinuation of the index treatment was the most common reason for censoring (82.6%), followed by day 365 (10.2%), end of the study period (3.4%), loss of Medicaid eligibility (3.3%), and occurrence of the outcome event (0.4%). There were minimal group differences in reasons for censoring. The adjusted hazard ratio for all-cause mortality comparing newer antipsychotic to antidepressant augmentation was 1.45 (95% confidence interval (CI), 1.02–2.06), with a risk difference of 37.7 (95%CI, 1.7–88.8) per 10,000 person-years. The adjusted Kaplan-Meier plot is shown in eFig 1 (S1 Appendix). No dose-response effect was apparent (eTable 5, S1 Appendix). Estimates were consistent when the endpoint was restricted to natural death (HR = 1.58, 95%CI 1.02–2.45) or non-cancer death (HR = 1.65, 95%CI 1.05–2.60). Risk for unnatural death showed a modest numerical increase but confidence intervals were consistent with both harmful and protective effects (HR = 1.21, 95%CI 0.63–2.34).

Stratified analyses.

Analyses stratified by age group and sex and for individual newer antipsychotics are shown in

Table 3. Newer antipsychotics were associated with a mortality risk of HR = 1.61 (95%CI 0.92–2.80) in older adult patients and a mortality risk of HR = 1.36 (95%CI 0.86–2.13) in younger adult patients. Newer antipsychotics showed an association with increased mortality risk among women (HR = 1.72, 95%CI 1.13–2.63), but not among men (HR = 0.99, 95%CI 0.52–1.87).

Analyses of individual newer antipsychotics.

When augmentation with individual newer antipsychotics was compared to augmentation with a second antidepressant, olanzapine showed the greatest increase in risk (HR = 1.92, 95% CI 1.10–3.33), followed by risperidone (HR = 1.66, 95%CI 1.01–2.74), quetiapine (HR = 1.18, 95% CI 0.77–1.82), and aripiprazole (HR = 0.88, 95%CI 0.42–1.86). Due to sample size limitations, stratified analyses and analyses of individual newer antipsychotics were considered exploratory and no formal interaction tests were performed.

Sensitivity analyses.

Sensitivity analyses related to follow-up period, study period, and propensity score implementation, yielded consistent findings (

Table 4). Adding discontinuation of the initial antidepressant to the censoring criteria for both treatment groups resulted in a loss of approximately 22% of follow-up time but did not meaningfully alter the results for all-cause mortality (HR = 1.47, 95%CI 0.95–2.28). Exclusion of patients with claims for mood stabilizers during the baseline period numerically increased the hazard ratio for all-cause mortality to 1.70 (95%CI 1.09–2.65). Results were sensitive to the implementation of propensity score trimming. In the untrimmed cohort, point estimates of the mortality hazard ratio moved towards the null hypothesis and hazard ratio confidence intervals crossed 1.0 (

Table 4). Propensity score stratified analysis indicated homogenous mortality risk in the central propensity score strata but strong heterogeneity in the trimmed tails of the propensity score (eTable 6, S1 Appendix). Unadjusted results for all inferential analyses are shown in eTables 7–9 (S1 Appendix).

Analyses adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, and index year were generally consistent with inverse probability of treatment-weighted results (eTable 10, S1 Appendix). A relative risk of approximately 3.8 linking a hypothetical confounder in 25% of the population to both newer antipsychotic use and mortality would be needed to fully explain the observed association in the primary analysis (eFig 2, S1 Appendix).

Discussion

Our study examined the mortality risk of newer antipsychotic augmentation for non-elderly adults with depression in a large cohort of US Medicaid insured patients. As compared to augmentation with an antidepressant, augmentation with a newer antipsychotic was associated with a 45% relative increase in mortality risk, equivalent, in our study population, to an absolute risk difference of 37.7 deaths per 10,000 person-years of treatment (0.38%/year). The magnitude of the observed relative increase in mortality risk is broadly similar to the findings of a meta-analysis of placebo-controlled randomized controlled trials for newer antipsychotics in elderly dementia patients (54%) (

15), a finding that triggered a class-wide black box warning for newer antipsychotics by the US Food and Drug Administration (

37).

Although the absolute mortality risk in patients with depression is markedly lower than in elderly patients with dementia, the magnitude of excess risk in the non-elderly depression group is substantial and warrants careful clinical consideration. A mortality rate difference of 37.7 per 10,000 years of follow-up corresponds to a number-needed-to-harm of approximately 265 per year. For higher risk subgroups the number-needed-to-harm decreases substantially, e.g., to 112 for patients between 55 and 64 years of age. Because of the small-to-moderate-size benefits of newer antipsychotic augmentation (meta analyses of newer antipsychotic augmentation RCTs estimate a number-needed-to-treat for remission of about 9) and lack of demonstrated benefit with regards to quality of life or functional impairment (

11,

18), the additional mortality risk associated with newer antipsychotics is of great clinical relevance. This is particularly the case for higher risk subgroups, and especially considering that nearly two-thirds of patients initiating newer antipsychotics for depression in the United States do not first receive a full antidepressant trial (

21).

Stratified analyses suggest potential clinically relevant heterogeneity by age, sex and choice of newer antipsychotic, with particularly high absolute risk differences in patients 55 to 64 years of age, women, and patients treated with olanzapine or risperidone. Importantly, the study’s power to examine these subgroups was limited and stratified results should be considered as hypothesis generating until refuted or confirmed by future research. Newer antipsychotic augmentation showed an association with increased risk for mortality in women but not in men. Although this finding may reflect chance, prior reports have suggested several adverse effects of antipsychotic medications, including weight gain, diabetes, and cardiovascular death may disproportionately affect women (

38). Further study is required to place the sex-stratified findings in context and elucidate potential mechanisms. There were also marked risk differences between individual newer antipsychotics. A higher mortality risk for olanzapine and risperidone than for quetiapine and aripiprazole aligns with studies in elderly patients with and without dementia (

39–

41), and with late life bipolar disorder (

42), but findings require independent refutation or confirmation.

When we restricted the analyses to mortality from natural causes or to non-cancer mortality, the point estimates increased and remained statistically significant. The estimate for unnatural death was numerically small and not statistically significant. Sample size limitations prevented examination of specific causes of death. In contrast to some prior studies in older adults (

39,

40), we found no strong evidence of a dose-response. However, these analyses used chlorpromazine equivalents, which are based on expert opinion rather than scientifically validated methodology, and were solely based on the initial newer antipsychotic dose ignoring dose titration over follow-up, and thus unable to identify anything other than a substantial dose-response effect.

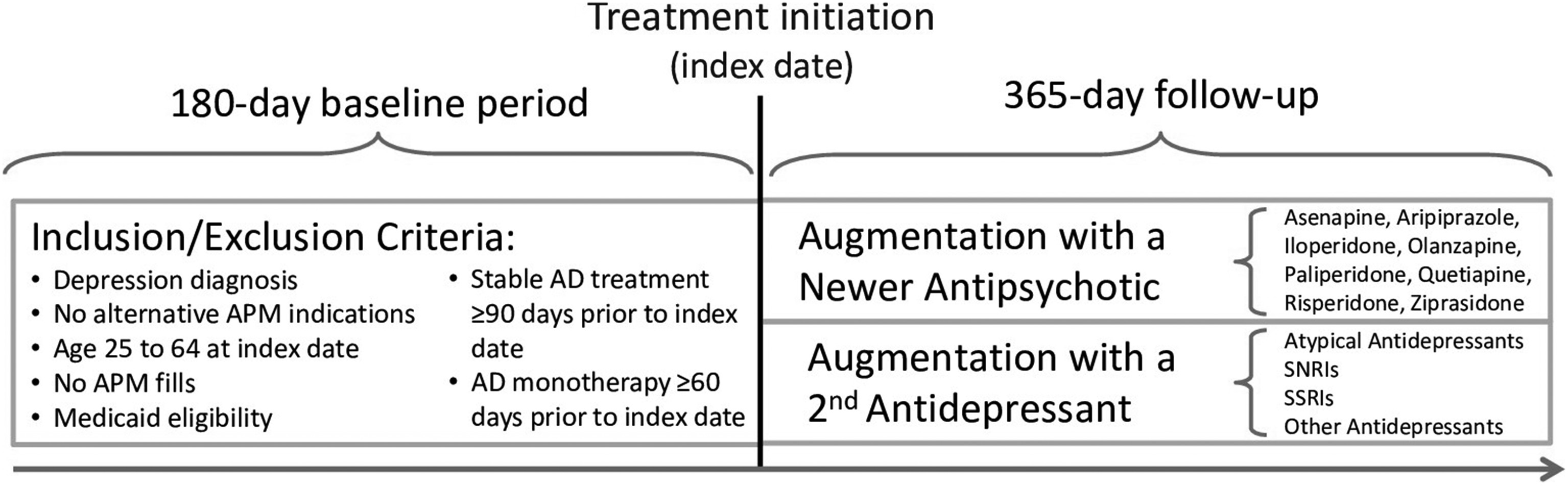

We selected augmentation treatment with a second antidepressant as the comparator group for this study as a means of controlling by study design for confounding by indication (

Fig 2). This approach assures that both treatment groups are solely comprised of patients who initiated one of two augmentation treatments after at least 60 days on antidepressant monotherapy (a proxy measure for inadequate response to the baseline treatment). Although augmentation with a second antidepressant does not constitute a FDA-approved treatment strategy, it is widely used in clinical practice and the most suitable active comparator for our study. The consequence is that our results are relative to this treatment alternative. In other words, it is possible that we overestimated the mortality risk of newer antipsychotic augmentation (in case antidepressant augmentation reduces mortality risk) or that we underestimated the true mortality risk of newer antipsychotic augmentation (in case antidepressant augmentation increases mortality risk). However, to our knowledge there is currently no evidence to suggest that antidepressant augmentation affects mortality risk in patients with treatment resistant depression.

Our study had some limitations. First, as a nonrandomized study, residual confounding by factors associated with both newer antipsychotic use and increased risk of death, such as unmeasured psychotic symptoms, cannot be completely excluded. However, quantitative sensitivity analysis demonstrates that a strong and prevalent unmeasured confounder would be needed to fully explain the observed association. Second, study results were sensitive to the protocol-specified implementation of propensity score trimming, which excluded a small proportion of the study population in the tails of the propensity score distribution due to concerns for unmeasured confounding. However, this approach was supported by the strong heterogeneity of newer antipsychotic-associated mortality risk in the extremes of the propensity score distribution (eTable 6, S1 Appendix). Third, the limited number of deaths did not allow a more detailed examination of cause-specific mortality that may have provided insight into biologic mechanisms. Fourth, although the inclusion criteria required a refill of the initial antidepressant on the day of the index fill of the second antidepressant to maximize the likelihood that the intent was augmentation with a second antidepressant, some patients may have initiated the second antidepressant with the intent to switch antidepressants, which could capture patients with a somewhat lower severity of depression in the antidepressant augmentation group than the antipsychotic augmentation group. Finally, the results, which are confined to the US Medicaid population, may not generalize to other populations of non-elderly adults who are treated for depression.