Introduction

Bipolar disorder is a common condition and cause of global disability (

1). Although it is defined by episodes of mania or hypomania, it is also characterised by chronic and recurring depressive episodes that account for a substantial proportion of disability (

2,

3). With an early age of onset (

4), patients are reported to spend as much as half of their lives with mood symptoms (

2).

There are several level 1 pharmacological strategies for the management of acute mania, but few level 1 treatments exist for acute bipolar depression (

5). Quetiapine, fluoxetine plus olanzapine, and lurasidone alone or in conjunction with lithium or valproate are the only treatments approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for bipolar depression. Many patients with bipolar depression either do not respond to these medications or have difficulty tolerating the side-effects. Thus, treatment for bipolar depression remains a substantial unmet need.

In view of the dearth of proven treatments, clinicians widely use antidepressants to treat acute bipolar depression (

6,

7). However, the effectiveness of these medications for the relief of depressive symptoms remains controversial because of the small evidence base. Previous meta-analyses that included data from studies of first-generation and second-generation antidepressants reported on the efficacy of antidepressants; of these, two suggest that antidepressants are more efficacious than placebo (

8,

9) whereas the third did not (

10). Overall, antidepressants were no more likely to switch patients into mania or hypomania (ie, affective switch) compared with placebo (

8,

10); however, additional analyses suggested that tricyclic antidepressants and SNRIs were more likely to induce mania than were SSRIs or bupropion (

8,

10,

11). Furthermore, little evidence suggests that non-SNRI second-generation antidepressants increase the risk of manic switch

8,

10,

12,

13.

The International Society for Bipolar Disorders (ISBD) expert consensus statement discourages the use of antidepressant monotherapy for the treatment of acute bipolar depression (

14). However, previous meta-analyses have not distinguished between antidepressant monotherapy and antidepressants as adjuncts to adequate mood stabilisation, and therefore this important clinical question remains unaddressed. Additionally, previous meta-analyses included studies of tricyclic anti depressants and inhibitors of monoamine oxidase, classes that carry an increased risk of affective switch and cycle acceleration (

15). Therefore, we aimed to determine whether second-generation antidepressant adjunctive therapy is efficacious and safe in the treatment of acute bipolar depression, a crucial consideration in clinical practice.

Results

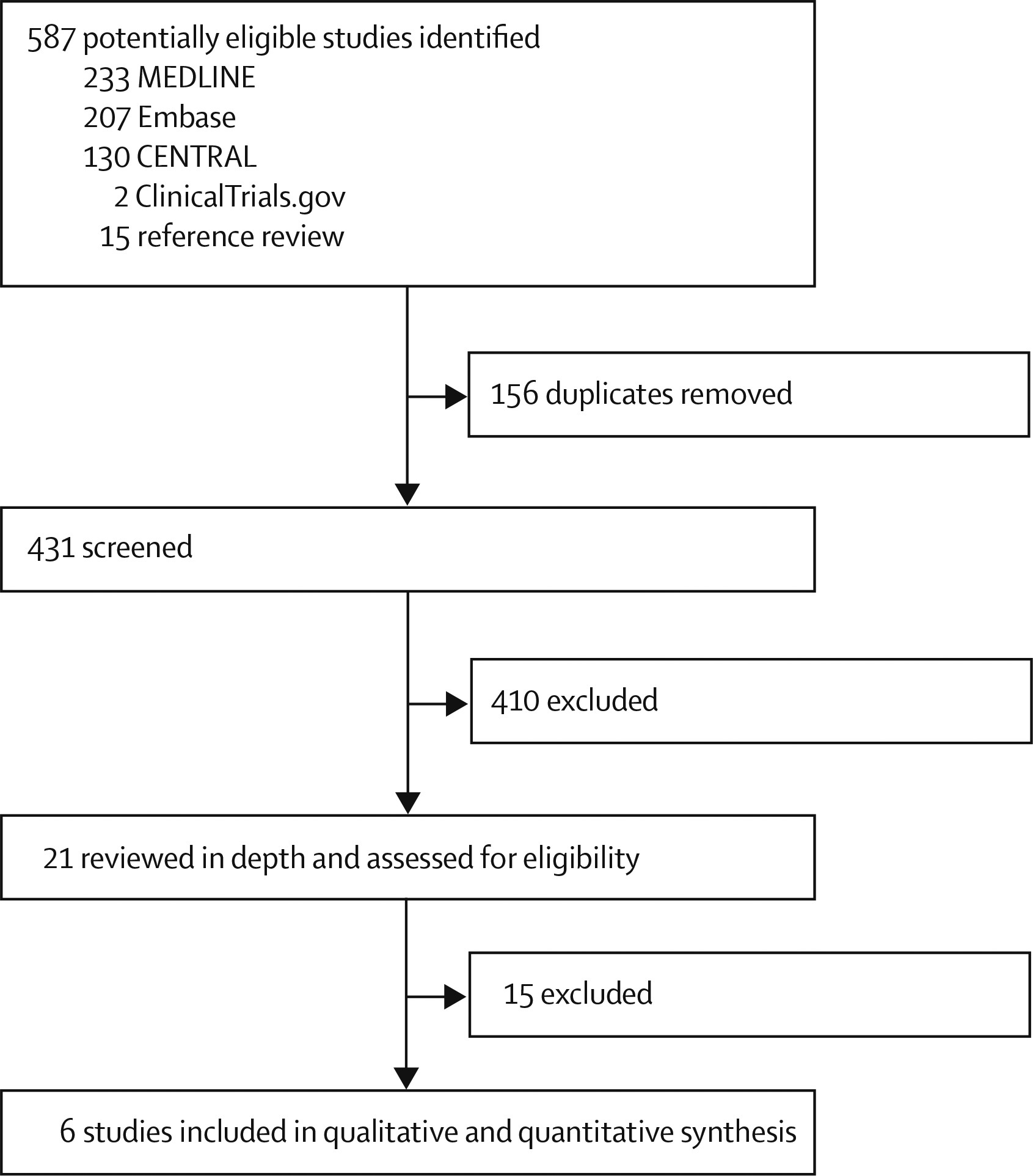

We initially identified 587 potentially eligible studies (

figure 1). Removal of duplicates and screening of titles and abstracts left 21 records, of which 14 were excluded after full-text review; all trials that were excluded because of the nature of the antidepressant also did not meet at least one other inclusion criterion (appendix). One trial identified from

ClinicalTrials.gov (NCT00464191) was also excluded because the trial was terminated owing to insufficient recruitment. We included the remaining five published studies (

12,

13,

26–

28) and an additional trial from

ClinicalTrials.gov (the CAPE-BD trial) (

29) in the meta-analysis. Assessment of risk of bias of the included studies is shown in the appendix.

Our meta-analysis included 1383 patients with bipolar disorder (1127 with bipolar I disorder, 166 with bipolar II disorder, 78 with DSM-III-R bipolar disorder, and 12 for whom the exact diagnosis was unspecified;

table). Three trials (

12,

26,

28) included only patients with bipolar disorder I, whereas three trials (

13,

27,

29) included both types of the condition. The mean age of patients was 41·93 years (SD 12·21), and the overall patient population consisted of 559 men and 822 women (sex of two patients was unspecified).

Five trials (

12,

13,

27–

29) involved patients using lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine for the duration of the trial, although the STEP-BD trial (

13) allowed patients to be on any FDA-approved antimanic agent in the final 2 years of recruitment (table). One study (

27) involved a three-group design and used risperidone in addition to lithium, valproate, or carbamazepine for mood stabilisation; of the three study groups, we included the groups receiving risperidone plus placebo and risperidone plus paroxetine. One trial used olanzapine (

26). SSRIs were the most studied class of modern antidepressants (paroxetine (

12,

13,

27), fluoxetine (

26), citalopram) (

29), in addition to 5-HT2B and 5-HT2C antagonist and melatonergic agonist (agomelatine) (

28) and norepinephrine–dopamine reuptake inhibitor (bupropion) (

13). In one trial (

13), patients were randomly assigned to receive either paroxetine or bupropion. We did not identify any placebo-controlled trials of SNRI adjunctive therapy. The duration of the trials were 6 weeks (

29), 8 weeks (

26,

28), 12 weeks (

27), and 26 weeks (

13).

For sensitivity analyses, we excluded the STEP-BD trial (

13) because it used the clinical monitoring form for mood disorders to define remission, whereas other studies used MADRS or HDRS. Furthermore, open-label treatment allowed psychiatrists to add antidepressants at their discretion after 6 weeks of placebo-controlled treatment. We also excluded the olanzapine–fluoxetine trial (

26) because this was the only study with findings supporting the efficacy of adjunctive antidepressant therapy.

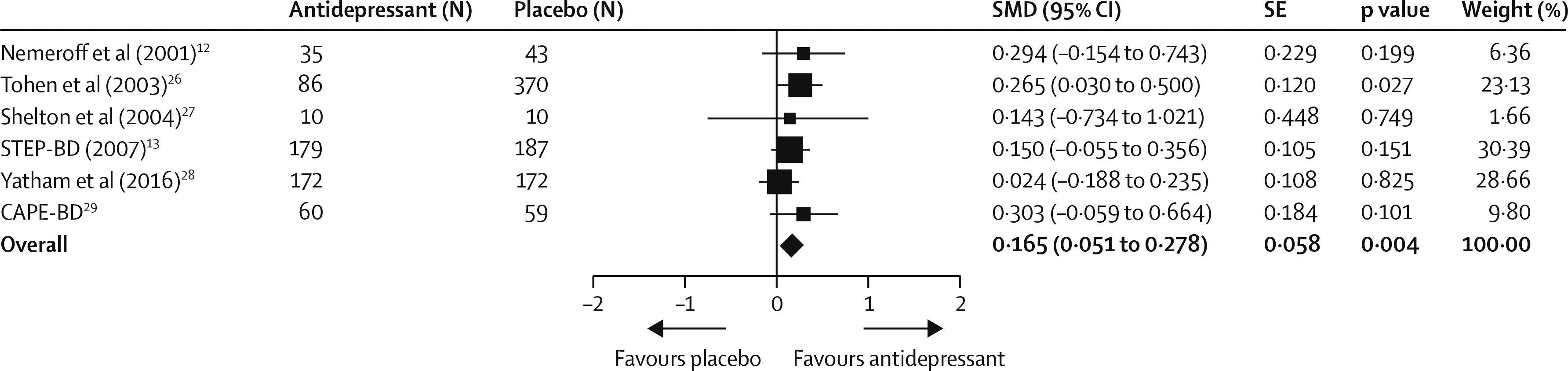

Depressive symptom scores were available for five trials (

12,

26–

29), and we obtained data for the remaining trial (

13) from the controlled access datasets distributed from the National Database for Clinical Trials (NCT00012558) supported by the US National Institute of Mental Health, which allowed us to extract clinician-rated depressive symptoms from the first 6 weeks (the double-blind period) of the trial without the confounding effect of subsequent antidepressants allowed by the protocol. However, symptoms were measured with different instruments, including MADRS (

26,

28,

29) HDRS (

12,

27), and clinical monitoring form (

13). We conservatively assumed a correlation coefficient of 0·7 in SMD calculation because we could not retrieve the correlations between scores before and after treatment for all trials (

30). Compared with placebo, adjunctive antidepressants were associated with a small but significant improvement in clinician-rated depressive symptoms (SMD 0·165 [95% CI 0·051–0·278], p=0·004;

figure 2). Between-sample heterogeneity was not significant, with a Q statistic of 3·30 and

I (

2) of 0·00 (degree of freedom [df]=5; p=0·65). In sensitivity analyses, effect sizes remained small when excluding the STEP-BD trial (

13) (0·171 [0·035–0·306], p=0·014) or the olanzapine–fluoxetine trial (

26) (0·134 [0·005–0·263], p=0·041). Heterogeneity between trials using a mood stabiliser and those using an antipsychotic was not significant (Q=0·60, df=1; p=0·43). Findings of the funnel plot (appendix) and Egger’s intercept (–0·75, t(4)=0·84; p=0·44) suggested a low possibility of publication bias.

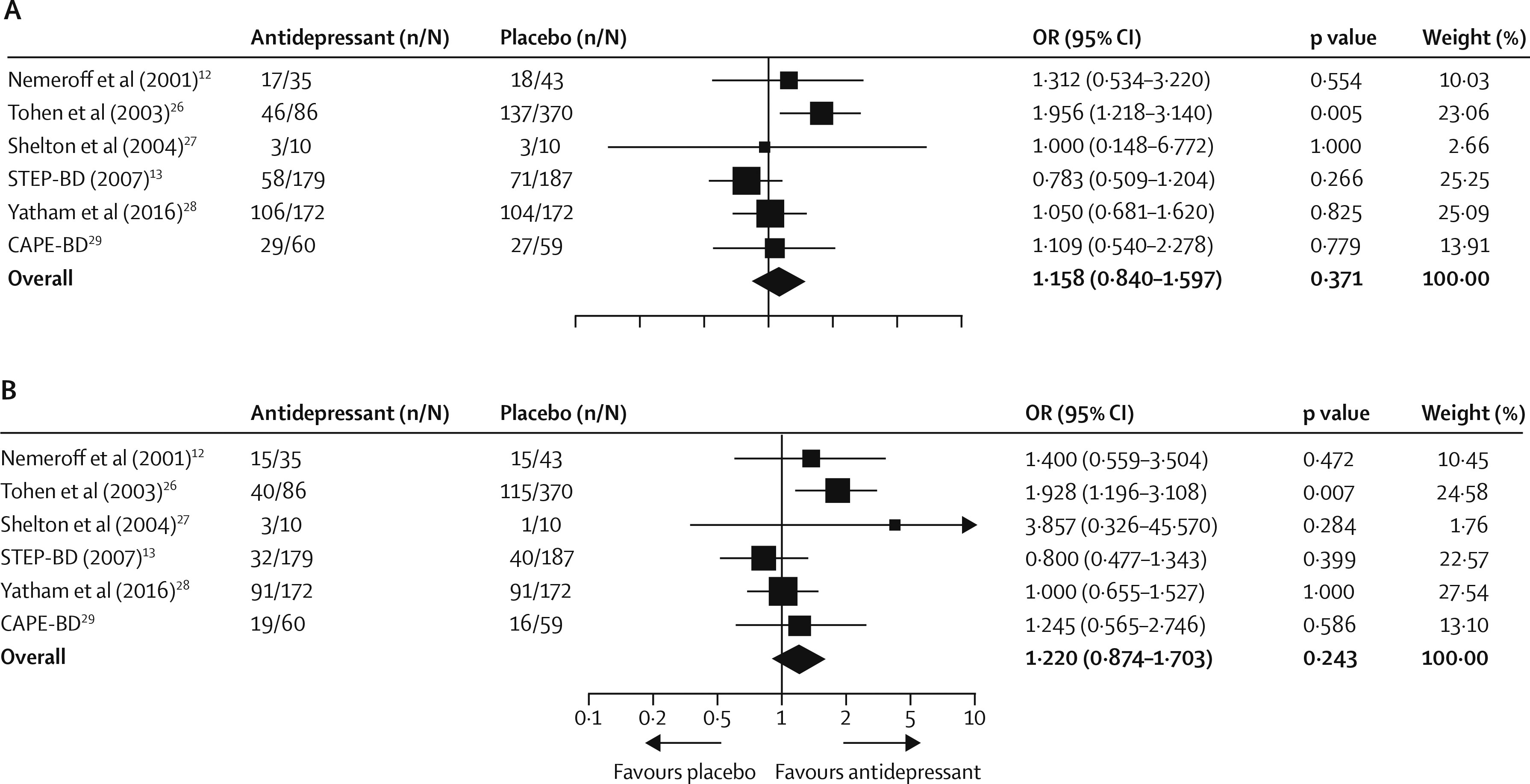

Data for response rates were available for all six trials. For the STEP-BD trial (

13), we used published outcomes for secondary analyses because the clinical monitoring form was used. By study end, 259 (48%) of 542 patients receiving antidepressants and 360 (43%) of 841 patients receiving placebo achieved response criteria. Pooled OR was 1·158 (95% CI 0·840–1·597, p=0·371;

figure 3A) and RD was 0·035 (–0·043 to 0·113, p=0·377). Exclusion of the STEP-BD trial (

13) enhanced the clinical response of antidepressants to a small degree (199 [55%] of 363

vs 286 [44%] of 654; OR 1·332 [1·010–1·756], p=0·042), corresponding to a number needed to treat of 15 (95% CI 8–250 000; RD 0·068 [0·000–0·137], p=0·046). There was heterogeneity between these trials, with a Q statistic of 8·35 and

I (

2) of 40·12 (df=5; p=0·13). We found heterogeneity between trials using mood stabilisers and those using antipsychotics (Q=6·13, df=1, p=0·013). Antidepressants were associated with increased clinical response in antipsychotic trials (OR 1·881 [1·188–2·979], p=0·007; RD 0·151 [0·040–0·263]; number needed to treat 7 [4–25]) but not in mood stabiliser trials (OR 0·963 [0·736–1·259], p=0·783; RD 0·029 [–0·026 to 0·084]). In patients receiving an antipsychotic, 49 (51%) of 96 patients receiving adjunctive antidepressants achieved clinical response, compared with 140 (37%) of 380 patients receiving placebo. By contrast, clinical response was achieved in similar proportions of patients given an antidepressant plus a mood stabiliser (47% [210 of 446]) and those given placebo plus a mood stabiliser (48% [220 of 461]). Additionally, we used meta-regression to test the relation between response RD and study duration, and found decreasing efficacy with increasing trial duration (slope –0·01 [95% CI –0·00 to –0·02]; Q=3·86, df=1, p=0·049). Examination of the funnel plots revealed one outlier (

26) (appendix), but Egger’s intercept (0·30, t(4)=0·30, p=0·77) did not suggest publication bias.

Data for remission rates were available for all six studies. By the study end, 200 (37%) of 542 patients receiving an antidepressant and 278 (33%) of 841 patients receiving placebo achieved clinical remission. Pooled OR was 1·220 (0·874 to 1·703, p=0·243;

figure 3B) and RD was 0·044 (–0·029 to 0·118, p=0·235). Sensitivity analyses revealed a marginal difference in favour of antidepressants when the STEP-BD trial (

13) was excluded (168 [46%] of 363

vs 238 [36%] of 654; OR 1·365 [0·985–1·891], p=0·061; RD 0·073 [0·003–0·144], p=0·042), with a number needed to treat of 14 (7–334). Overall, there was evidence of heterogeneity between the studies (Q=8·42,

I2=40·67, df=5, p=0·13). Heterogeneity between trials using a mood stabiliser and those using an antipsychotic was significant (Q=6·01, df=1, p=0·014), an effect that persisted when the STEP-BD trial (

13) was excluded (Q=3·96, df=1, p=0·046). This finding suggested that the efficacy of antidepressants was greater in antipsychotic trials (OR 1·977 [1·237–3·159], p=0·004; RD 0·159 [0·050–0·268], number needed to treat 7 [4–20]), but not in mood stabiliser trials (OR 0·993 [0·745–1·324], p=0·964; RD 0·030 [–0·021 to 0·081]). 43 (45%) of 96 receiving an antipsychotic plus an antidepressant achieved remission criteria, compared with 116 (31%) of 380 patients treated with an antipsychotic and placebo. By contrast, in patients given a mood stabiliser, remission rates were similar in those receiving an antidepressant (35% [157 of 446]) and in those receiving placebo (35% [162 of 461]). Although Egger’s intercept (1·75, t(4)=1·43, p=0·22) did not suggest publication bias, visual inspection of funnel plots indicated a skewed distribution (appendix).

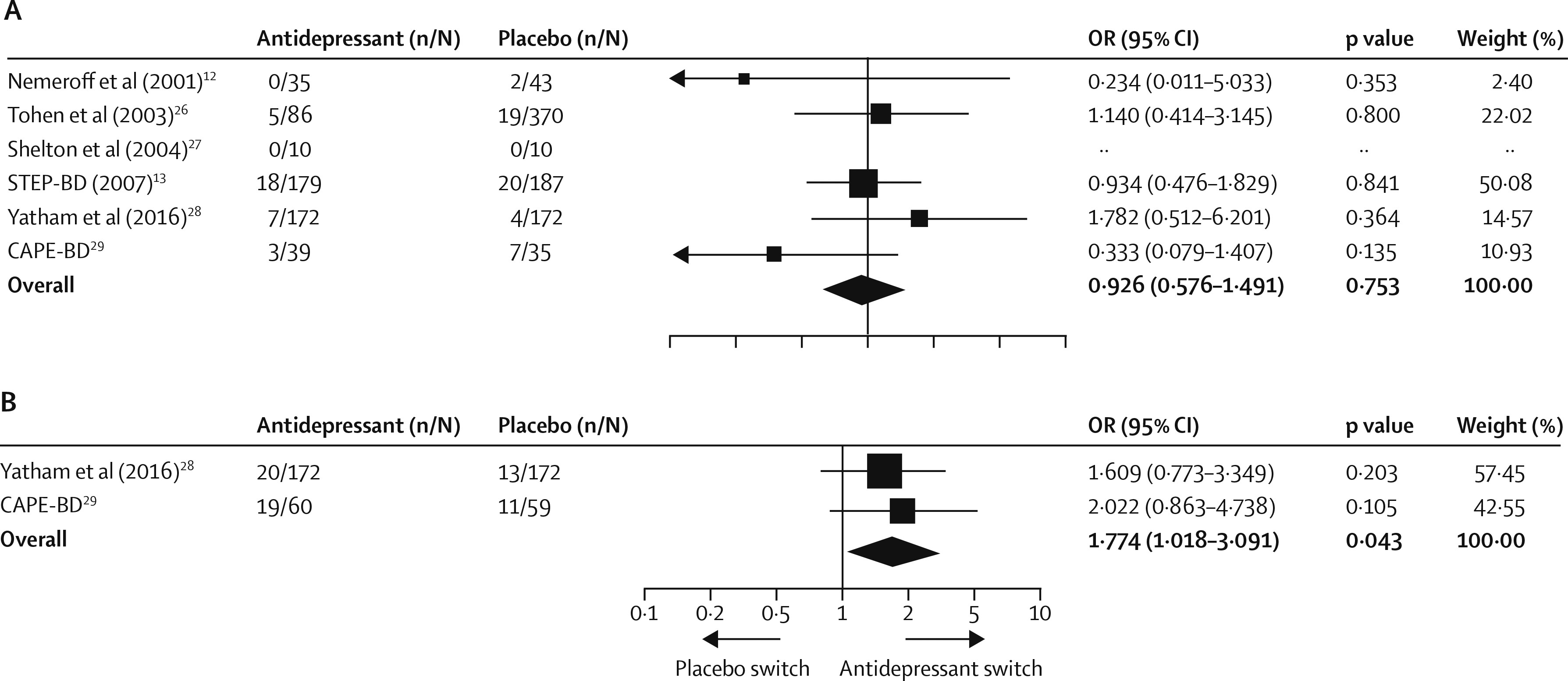

The rates of acute treatment-emergent mania or hypomania were available for all six studies; however, in one trial (

29), such data were available for only half the participants because these data were not collected at one of the participating sites. Two studies (

28,

29) had data for 52 week extensions of treatment. At the end of the acute phase of treatment, 33 (6%) of 521 patients given antidepressants and 52 (6%) of 817 patients given placebo had episodes of treatment-emergent mania or hypomania, and antidepressant therapy was not associated with an increased risk of affective switch (OR 0·926 [0·576 to 1·491], p=0·753; RD 0·000 [–0·025 to 0·026], p=0·971;

figure 4A). Sensitivity analyses did not reveal effects of either the STEP-BD trial (

13) (p=0·91) or the olanzapine–fluoxetine trial (

26) (p=0·73) on the risk of affective switch. Metaregression did not show a significant relation between risk and study duration (Q=2·51, df=1, p=0·11). Heterogeneity between studies was not significant (Q=3·77,

I2=0·00, df=5, p=0·58), and subgroup analyses showed no statistical difference between studies using a mood stabiliser or an antipsychotic (Q=0·09, df=1, p=0·75), although interpretability of both is limited by the small number of studies. The asymmetrical funnel plot (appendix) and Egger’s intercept (–1·48, t(4)=2·33, p=0·079) suggested publication bias. When considering the two studies with 52 week treatment extensions (

28,

29), adjunctive antidepressant therapy was associated with an increased risk of treatment-emergent affective switch (39 [17%] of 232

vs 24 [10%] of 231; OR 1·774 [1·018–3·091], p=0·043; RD 0·053 [–0·004 to 0·111], p=0·070; number needed to harm 19;

figure 4B).

Overall, 164 (30%) of 542 patients given antidepressants and 323 (38%) of 841 those given placebo were lost to follow-up (OR 0·897 [0·637–1·262], p=0·532; appendix). There was evidence of heterogeneity between studies, with a Q statistic of 7·89 and

I (

2) of 36·68 (df=5, p=0·16). In subgroup analysis, dropout rates were higher in antipsychotic trials (49% [231 of 476]) than in mood stabiliser trials (28% [256 of 907]; Q=6·17, df=1, p=0·013), mostly driven by dropouts in patients given placebo plus antipsychotic (196 [52%] of 380). Funnel plots revealed one outlier (

26) (appendix), but Egger’s intercept (0·23, t(4)=0·16, p=0·87) did not suggest publication bias.

Discussion

Although previous meta-analyses have examined the safety and efficacy of antidepressants in bipolar depression, the clinical relevance of their findings is limited by the inclusion of studies of antidepressant monotherapy as well as tricyclic antidepressants and inhibitors of monoamine oxidase. We restricted our analyses to randomised, placebo-controlled trials that tested the efficacy of second-generation antidepressants versus placebo adjunctive to a mood stabiliser or an atypical antipsychotic. Therefore, our analyses provide data to inform not only efficacy but also the risk of treatment-emergent affective switches when following ISBD recommendations (

14). Our findings show that second-generation antidepressants, when used in combination with a mood stabiliser or an atypical antipsychotic, have a significant but small effect size and are not associated with notable acute mania or hypomania switch risks. The small effect size did not translate into increased clinical response or remission; however, we noted statistical separation for the subgroup of trials using an antidepressant as an adjunct to an antipsychotic.

With the exception of the STEP-BD trial (

13), clinical trials of acute bipolar depression are typically 6–8 weeks in duration. Therefore, to compute the mean change in depressive symptoms for inclusion in our metaanalysis as a primary outcome, we extracted data from the 6 week double-blind period from the 26 week STEP-BD trial (

13). Another important consideration when examining data from these trials is the high rates of clinical remission and response in the placebo groups. Indeed, in one 8 week randomised controlled trial (

28), remission rate in the placebo group was as high as 53% (

28). Remission rates of patients given placebo in trials of schizophrenia and depression have been increasing (

31,

32). Although placebo responses are relatively stable in acute mania trials and do not seem to interfere with detection of the efficacy of antimanic treatments, placebo responses have been steadily increasing in bipolar depression trials (similar to the situation seen in trials of major depression) (

28,

33,

34), which substantially interfere with the detection of efficacy signals. Therefore, strategies to address increasing placebo response rates are urgently needed in trials in psychiatry.

The risk of short-term treatment-emergent affective switches with antidepressant treatment in bipolar depression is one of the most contentious issues in the mood disorder literature. As has been highlighted (

14), the fluctuant nature of mood in bipolar disorder makes the assignment of causality difficult. Yet, the use of antidepressant monotherapy is clearly associated with an increased risk of mania (

6) and is discouraged by expert recommendations (

14). Moreover, several agents—notably, tricyclics, tetracyclics, and SNRIs—have been associated with an increased risk of short-term treatment-emergent affective switch (

8,

10,

11,

35). Although concern and caution have spread to all antidepressants, other classes of antidepressants such as SSRIs and other antidepressants, such as bupropion, have not separated from placebo in meta-analyses (

10,

36).

Although additional trials are needed because the assumption of a class effect might ultimately prove erroneous, we did not find an increased risk of short-term treatment-emergent affective switches with adjunctive second-generation antidepressant therapy during acute treatment of bipolar depression in this population with predominantly bipolar I disorder. However, definitions of treatment-emergent mania differed among the trials, and more sensitive measures could reveal changes and be best suited to identify cycle acceleration (

37). Accordingly, although we did not identify a risk with time-limited use of adjuntive second-generation antidepressants, the risk of treatment-emergent mania or hypomania increased with prolonged use (in 52 week placebo-controlled extensions) despite adequate mood stabilisation (number needed to harm 19) (

28,

29). Thus, prolonged treatment might be detrimental, as reflected in international guidelines (

5) and recommendations from the British Association for Psychopharmacology (

38). However, this conclusion is provisional and based on only two trials, and additional investigation is needed.

A limitation of our meta-analysis was the multiple sources of diversity between the trials included (different antidepressants, mood stabilisers, and antipsychotics, outcome metrics, and durations of study). Indeed, statistical heterogeneity was noted in analyses of clinical response and remission, which seemed attributable to the use of mood stabilisers versus antipsychotics. Unfortunately, the small number of studies limited our exploration of clinical or methodological causes of heterogeneity beyond trials using mood stabilisers and those using antipsychotics. The study with the greatest antidepressant effect size (

26) driving heterogeneity involved a washout period followed by initiation of the study intervention, whereas the remainder trials all required stable psychotropics before trial commencement. One study (

29) had incomplete data with respect to treatment-emergent affective switches in the acute phase. Our findings should be interpreted in light of both type I and type II errors, and the possible effects of multiple testing in secondary outcomes. Differential remission rates between antipsychotic and mood stabiliser trials should be interpreted in light of the high dropout rate (>50%) in antipsychotic plus placebo trials.

The literature itself is subject to limitations, including a small number of randomised controlled trials, elevated placebo effects, and methodological exclusion of patients with rapid cycling courses or comorbid substance use disorders. Furthermore, trials have not yet systematically addressed other important questions with a double-blind design, such as the risk of depressive relapse with antidepressant discontinuation in patients who respond to second-generation antidepressants as an adjunct to mood stabilisers or antipsychotics. Such data might modify the risk-benefit assessment of prophylactic treatment.

Our meta-analysis of randomised placebo-controlled trials of second-generation antidepressants in conjunction with a mood stabiliser or an antipsychotic in acute bipolar depression suggests that they have a small antidepressant effect, and short-term use of these medications is not associated with an increased risk of treatment-emergent affective switches. This supports first-line recommendations by the joint guidelines of ISBD and the Canadian Network for Mood and Anxiety Treatments (CANMAT) (

5). Antidepressants are well tolerated acutely, although subthreshold manic symptoms have not been adequately characterised. However, antidepressants are accompanied by an increased risk for manic or hypomanic episodes with prolonged use and therefore only time-limited use is supported by our analysis.