Military service members and veterans sustain traumatic brain injuries (TBIs) in accidents, training, combat, and avocational activities. Most TBIs occur from closed head injuries, as the result of acceleration-deceleration forces, blunt trauma, blast exposure, or some combination of these mechanisms. These injuries occur on a broad continuum of severity, from very mild transient injuries to catastrophic injuries resulting in death or severe disability.

By convention, TBIs are typically classified as mild, moderate, or severe, according to Glasgow Coma Scale scores, duration of loss of consciousness, and posttraumatic amnesia. A large majority of TBIs among civilians and military service members are mild in severity. A definition of mild traumatic brain injury (MTBI), provided by the World Health Organization Collaborating Center Task Force on Mild Traumatic Brain Injury, is as follows:

MTBI is an acute brain injury resulting from mechanical energy to the head from external physical forces. Operational criteria for clinical identification include: (i) 1 or more of the following: confusion or disorientation, loss of consciousness for 30 minutes or less, post-traumatic amnesia for less than 24 hours, and/or other transient neurological abnormalities such as focal signs, seizure, and intracranial lesion not requiring surgery; (ii) Glasgow Coma Scale score of 13–15 after 30 minutes post-injury or later upon presentation for healthcare. These manifestations of MTBI must not be due to drugs, alcohol, medications, caused by other injuries or treatment for other injuries (e.g. systemic injuries, facial injuries or intubation), caused by other problems (e.g. psychological trauma, language barrier or coexisting medical conditions) or caused by penetrating craniocerebral injury. (

1, p. 115)

MTBIs are common among post-9/11 service members and veterans (

2–

5). Approximately 10%−23% of service members returning from Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn meet criteria for having sustained an MTBI (

3,

6). On the basis of numerous studies of sport-related concussions among civilians (

7), most service members who sustain these injuries might be expected to make a full clinical recovery within days or weeks after injury. However, a substantial portion of civilians recruited from the emergency department (

8) or from specialty clinics (

9) report persistent symptoms and problems for months or years after injury. Moreover, in a recently published prospective, longitudinal study of active-duty U.S. military service members who sustained in-theater concussive-blast injuries, 72% declined in their overall functioning between one year and five years after injury, and worsening of postconcussion symptoms was common (

10). The reasons for the decline were unclear but were related in part to worsening mental health.

An estimated 12%−20% of post-9/11 service members and veterans meet criteria for posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

2–

4,

11), and approximately 6%−7% experience both MTBI and PTSD (

12). Further complicating this picture is the fact that many post-9/11 veterans struggle with multiple psychiatric and health conditions, including high rates of depression, anxiety disorders other than PTSD, substance misuse, chronic pain, and sleep difficulties (

3,

13,

14). The literature examining the impact of comorbidities among post-9/11 veterans with a history of MTBI, however, is currently limited.

Complex Comorbidities and Psychosocial Problems

One study found that having multiple comorbid conditions (i.e., depression, PTSD, and deployment-related MTBI) was associated with more substantial disability among service members and veterans (

14). A better understanding of the co-occurrence of different health and psychosocial problems among treatment-seeking post-9/11 service members and veterans with a history of MTBI is important for several reasons. The large overlap in symptoms of PTSD, MTBI, and other psychiatric disorders (

15,

16) can often complicate or obscure clinicians’ diagnostic decision making. Furthermore, the potential interactive and cumulative effects of multiple health conditions, psychosocial problems, and psychiatric disorders may affect treatment selection, planning, and outcomes. Finally, examining the potential impact of multiple comorbid conditions, psychosocial problems, and symptom burden can help provide a more complete picture of the challenges that veterans face in reintegrating into civilian and family life and further clarify their treatment needs.

A substantial percentage of post-911 veterans have chosen to access care in the private sector, outside the Veterans Affairs (VA) health care system (

17). Therefore, it is important for private-sector health care providers, in addition to VA providers, to better understand the complexities of presentation of those with reported MTBIs, including mental health problems, other health problems, and psychosocial problems. In this article, we describe a sample of treatment-seeking post-9/11 U.S. service members and veterans who reported having a history of MTBI and who were seen outside of the VA health care system, at a nonprofit specialty outpatient clinic. In particular, we present common psychiatric diagnoses and the frequency of comorbid disorders; psychosocial functioning (e.g., employment, social relationships, and family functioning); and the relationship among clinical diagnoses, symptom burden, and quality of life.

Home Base Outpatient Program

Home Base, a Red Sox Foundation and Massachusetts General Hospital program, provides outpatient mental health and TBI services to veterans and families, regardless of ability to pay or discharge status (

18). TBI services include comprehensive evaluations by specialists in rehabilitation medicine and neuropsychology. From those evaluations, referrals to other services are made on a case-by-case basis, such as for physical therapy (i.e., multimodal or vestibular), neuroendocrinology, headache specialty evaluation and treatment, or cardioautonomic evaluation.

TBI services are provided alongside mental health and addictions services in an integrated team model that ensures that veterans and their families receive or are connected to uniquely tailored care for both their TBI-related and their mental health needs. In fact, most patients with a history of MTBI who attend our outpatient program receive mental health, substance abuse, social work, and case management services as their primary services. They do not need specialty referrals to other providers. A subgroup of our patients have been identified as needing more intensive medical and rehabilitation services in addition to mental health services.

All patients seen at Home Base are asked to complete a battery of questionnaires during their first clinic visit and undergo a diagnostic evaluation by a licensed psychologist or a licensed psychiatrist. New patients are discussed at multidisciplinary rounds. Primary and secondary diagnoses from the DSM-IV and DSM-5 are reviewed by the clinical team and documented. For this study, we analyzed questionnaire data and clinical diagnoses emerging from these clinical intake assessments for the subset of patients who reported a prior history of MTBI.

The assessment includes diverse patient-reported outcome measures of traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, stress, anger, substance abuse, complicated grief, family functioning, and quality of life. The PTSD Checklist (PCL-C) (

19) and the Depression, Anxiety, Stress Scale–21 (DASS-21) (

20) were used as primary measures of symptom burden for this sample of patients. Additional measures included the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire (

21), Brief Anger-Aggression Questionnaire (

22), Alcohol Use Identification Test-C (

23), Inventory of Complicated Grief, and McMaster Family Assessment Device (

24). These measures are described in

Box 1.

Demographic Characteristics of the Patient Cohort

Between May 2012 and June 2015, 129 post-9/11 U.S. active-duty military service members and veterans with a history of MTBI or moderate TBI sought treatment at Home Base. Of those, 95% (N=123) were men, with a mean±SD age of 32.7±7.9. They indicated that their current or former branch of service was as follows: Army (N=75; 58%), Marines (N=40; 31%), Navy (N=6; 5%), or Air Force (N=5; 4%). Most reported at least one deployment (79%; N=93). A total of 55 (47%) reported that they were in a relationship (missing data; N=13; 10%), and only 15 (13%) indicated that they were employed (missing data; N=13; 10%).

Clinical Characteristics of the Patient Cohort

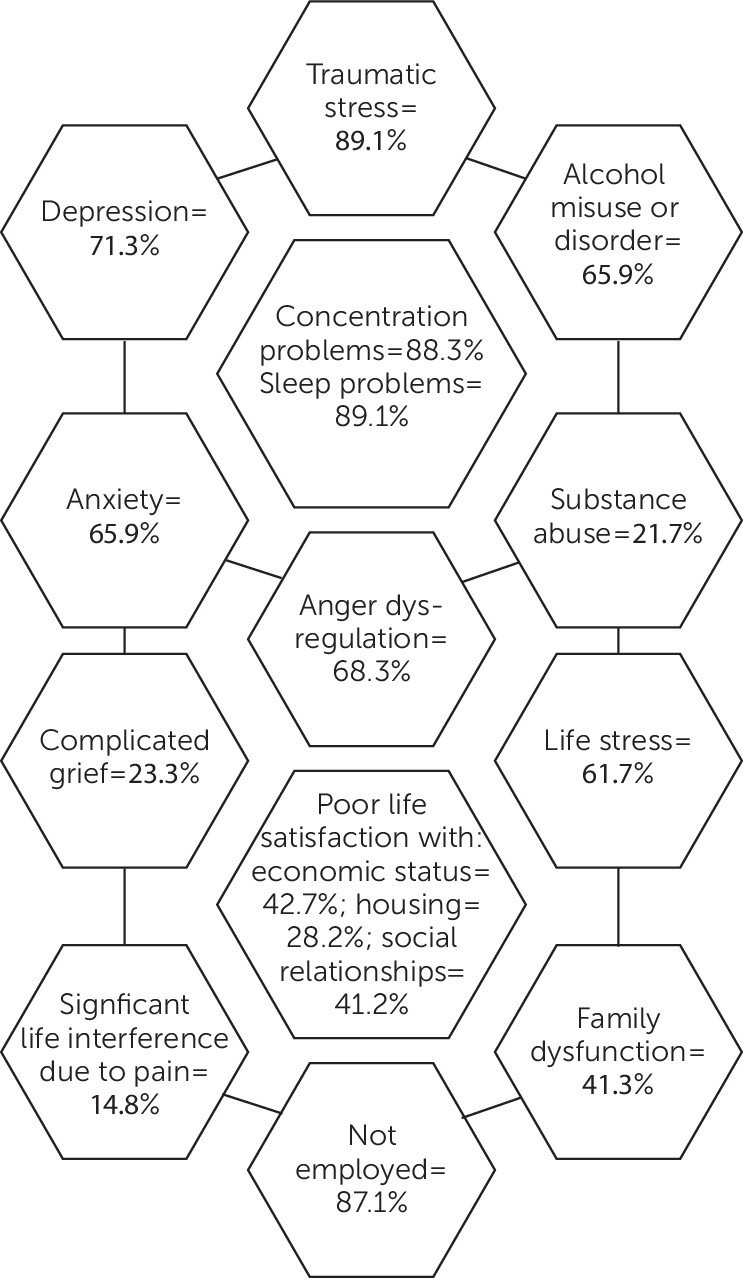

Clinical characteristics of the cohort are presented in

Table 1 and

Figure 1. The most common psychiatric diagnoses were PTSD (N=113; 88%), depression (i.e., major depressive disorder, depressive disorder not otherwise specified, mood disorder not otherwise specified; N=57; 44%), alcohol abuse (N=56; 43%), and substance misuse or abuse (N=28; 22%). Multiple diagnoses were common in this sample, with a majority of patients meeting criteria for two or more clinician-rated diagnoses (N=95; 74%), and 36% being diagnosed by their clinician as having three or more conditions. Note that in

Figure 1, the percentages reported include results from both clinician-rated diagnoses and patient-reported outcomes (e.g., clinician diagnosis of PTSD or a PCL-C total score of 50 or greater; see

Table 1 for more information). The calculations of multiple diagnoses or psychosocial problems are independent of, and do not include, a person’s history of MTBI.

Table 1 also summarizes the self-reported psychological health and psychosocial problems. These are described based on the number of those who completed each measure. As seen in

Table 1, of those who completed the PCL-C, 72% endorsed scores indicative of a possible diagnosis of PTSD (i.e., ≥50) (

19). According to recommended cutoff scores from the DASS-21, 62% endorsed moderate or greater symptoms of depression, 68% reported moderate or greater symptoms of anxiety, and 62% reported moderate or greater symptoms of stress. A total of 37% endorsed moderate or greater symptoms on all three scales of the DASS-21.

According to the Alcohol Use Identification Test-C’s suggested cutoff criteria, 59% of men and 33% of women endorsed scores indicative of hazardous drinking or active alcohol use disorders (i.e., cutoff scores of 4 and 3, respectively). Examining individual items on the PCL-C revealed that most patients (89%) reported moderate or greater problems with falling or staying asleep. Cognitive problems were very commonly reported on the PCL-C; 88% endorsed moderate or greater difficulties with concentration in the past 30 days. More than half of the patients (i.e., 59%) endorsed anger and aggression symptoms suggestive of anger dysregulation. The experience of complicated grief was reported by 29%. Of those who completed the General Functioning subscale of the McMaster Family Assessment Device, 41% (N=38) scored below the cutoff, which suggests family dysfunction.

Patients also completed questions regarding pain as part of their evaluation (N=122). Almost all endorsed some degree of pain in the past seven days (i.e., 92%; N=112), and one-third (34%) endorsed experiencing pain as ≥7 on a 10-point scale. A large proportion (i.e., 68%; N=83) indicated that their pain interfered at least somewhat with their day-to-day activities, and 15% indicated that their pain “very much” interfered with their day-to-day activities.

A questionnaire regarding participants’ perceived quality of life was also administered (Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire; N=110; 85%). Quality of life for these veterans with a history of TBI decreased as the number of psychiatric diagnoses or psychological health problems increased (Spearman r=−.34, p<.001; N=110). As seen in

Table 1, 87% of the participants were not employed. Of those who completed the Quality of Life Enjoyment and Satisfaction Questionnaire, 49% (N=54) reported poor satisfaction (i.e., score of 2 or less; “poor” or “very poor” satisfaction) with their work situation, 43% (N=47) endorsed poor satisfaction with their economic status, and 28% (N=23) endorsed poor satisfaction with their current living or housing situation. The aspects of psychosocial functioning that were most frequently endorsed as being poor included leisure time activities (52%, N=57), work (49%, N=54), mood (46%, N=21), sexual drive or interest (43%, N=47), economic status (43%, N=47), household activities (42%, N=46), social relationships (41%, N=45), and family relationships (40%, N=44).

Comparison With Prior Studies

The co-occurrence of TBI with different health, mental health, and psychosocial problems may complicate diagnostic decision making, treatment planning, and outcomes. Previous studies describing the co-occurrence of two or three mental health conditions among service members have suggested that comorbid conditions are common with TBI. In a study of 284 Operation Enduring Freedom, Operation Iraqi Freedom, and Operation New Dawn veterans from the VA Boston TBI Center for Excellence, 51% met criteria for three or more comorbid conditions (

14).

Another study of comorbid mental health conditions among 106,726 U.S. veterans returning from Iraq and Afghanistan seen at VA health care centers found that 29% had two comorbid diagnoses, and one-third had three or more (

5). When compared with the general population, rates of comorbid conditions among service members and veterans seem to be higher. The National Comorbidity Survey Replication found that of individuals with a mental health diagnosis (N=3,122), 22% had two diagnoses, and 23% had three or more diagnoses (

29).

We examined comorbid conditions in a sample of treatment-seeking veterans with a history of MTBI and found that the vast majority had numerous mental health concerns, with approximately 75% meeting criteria for two or more clinician-rated psychiatric conditions. In this patient cohort, 88% were diagnosed by their clinician as having PTSD. The most common clinician-based psychiatric diagnoses were depression, alcohol use disorders, and substance abuse. The majority either had a clinician diagnosis of depression or screened positive for depression on the DASS-21 (i.e., 71%).

More than half of all patients endorsed hazardous drinking levels on a brief screening measure (59%), and 43% received a clinician diagnosis of an alcohol use disorder. One in five (22%) were diagnosed as having a substance abuse disorder. This illustrates the high rate of alcohol and substance abuse among post-9/11 veterans with a history of MTBI and emphasizes the need for careful evaluation and concurrent treatment. When clinical diagnoses, psychological health, and psychosocial problems were examined together, the vast majority of veterans with a history of MTBI were experiencing five or more problems or conditions (i.e., 73%), and 41% had seven or more (

Table 1).

In our sample with a history of TBI, we observed worse quality of life among service members and veterans who endorsed greater symptom burden on measures of PTSD and depression. Poorer quality of life was also associated with a greater number of psychiatric diagnoses and psychosocial problems. The impact of psychological distress and psychosocial problems seemed to affect multiple aspects of quality of life, including occupational, social-relational, and psychological.

Conclusions

This cohort of treatment-seeking post-9/11 veterans with a history of MTBI presented with multiple psychiatric diagnoses, psychological health problems, psychosocial difficulties, and poor quality of life. The description of this cohort of patients adds to and expands the extant literature because most prior studies are conducted within the VA health care system and this study included a much broader clinical assessment than prior studies. Hazardous drinking, anger and aggression, pain, sleep difficulties, concentration problems, complicated grief, unemployment and disability, and relationship distress complicated the clinical presentation of these patients. The majority of patients had five or more major problem areas. It is important to consider these complex, interwoven psychiatric, behavioral, and psychosocial difficulties in the treatment-planning process. It is also necessary to implement and coordinate multidisciplinary treatment to ensure that service members’ and veterans’ diverse health, mental health, and social problems are adequately addressed. Integrated programs that provide multiple levels of care, treatment coordination, and social support can reduce barriers to care and improve outcomes.