This is an era characterized by rapid global communication networks and by diverse cultural perspectives and traditions woven into the fabric of contemporary life. It is a time in which modern transportation facilitates movement of people—sometimes fleeing war, famine, violence, and persecution—leading to shifting demographic profiles. These phenomena are often accompanied by political division, ethnocentrism, racism, and nativism, with populations such as immigrants and people of color sometimes made the targets of discrimination, bias, and hate. With nearly 40% of Americans identifying as a member of a racial or ethnic minority group (

1) and a remarkable intersectionality of identities shaping the social landscape, the context in which psychiatry is practiced in the United States is evolving.

For some, perhaps especially for those who are regarded as outsiders or who are marked by difference from the perceived cultural norm—in other words, people who are minoritized—this sociocultural landscape contributes to traumatic experiences. Being a target of racism, losing a parent to deportation, living in an unsafe neighborhood, being homeless, living in a war zone, and being involved with the criminal justice system are examples of traumatic experiences (

2–

9), and those who have experienced them are often overrepresented in minoritized communities (

10). Recent research has sparked new insights into trauma’s causes; its physiological and health effects; and how changing social, cultural, economic, and physical environments shape individual responses to and either buffer or potentiate trauma (

11–

13). As understanding of the complexity of trauma and its sociocultural context evolves, a flexible, holistic paradigm that considers social and cultural factors is needed to optimize diagnosis and treatment.

Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care

According to the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration,

Individual trauma results from an event, series of events, or set of circumstances that is experienced by an individual as physically and emotionally harmful or threatening and that has lasting adverse effects on the individual’s physical, social, emotional, or spiritual well-being. (

15)

Medical professionals are increasingly aware of how widespread trauma is and what a profound impact it can have. Potentially traumatic events affect a significant proportion of the population and can have physical, mental, emotional, and behavioral health consequences. Among women seeking treatment for substance abuse and public mental health services, 80%−90% have experienced personal violence and trauma, typically as a series of events that occur across the lifespan (

16). Upward of 90% of persons presenting for treatment of conditions such as anxiety and depressive disorders, personality disorders, substance abuse, and eating disorders, as well as those in contact with the criminal justice system, are estimated to have been exposed to significant emotional, physical, or sexual abuse in childhood (

17). Such figures have led to trauma being identified as a public health crisis (

16).

The landmark Adverse Childhood Experience (ACE) Study (

18) revealed that potentially traumatic events such as abuse, neglect, and household dysfunction are directly associated with severe physical, mental, and behavioral health consequences such as depression and risk for suicide. This is the case even in the absence of widely used diagnostic criteria for trauma-related disorders such as those found in the

DSM-5. Social inequities were not considered in the original ACE Study, in which the subjects were mostly white, middle and upper middle class, and college educated and had access to high-quality health care. Despite the relative privilege of the initial subject population, 67% of the participants had experienced at least one ACE. Subsequent research has broadened both the study population and what constitutes adversity, taking social determinants of health into account (

1) and revealing significantly greater mean ACE scores among disadvantaged populations (

19). Adopting a trauma-informed approach is one effort by mental health providers to address the prevalence of trauma and ACEs when diagnosing and treating all patients (

4,

18–

20).

Trauma-informed care is a strength-based approach to caring for individuals mindfully, with compassion and clarity regarding boundaries and expectations, to avoid unintentionally triggering a trauma or stress response. Trauma-informed care acknowledges that many people have experienced potentially traumatic events and that the health consequences of such events are significant. It recognizes that unique individual and previous life experience, including physical, social, and cultural environments, may influence how people respond to potentially traumatic events and how they receive, experience, and interact with their health care. Trauma-informed care is being adopted within and across health care, educational, legal, governmental, and agency settings in an acknowledgment that trauma is a societal issue (

15,

21). In the clinical setting, trauma-informed care requires structuring each patient encounter in such a way as to facilitate healing and foster resilience.

Principles that undergird trauma-informed care include empowerment, choice, collaboration, trustworthiness, and safety and a person-centered care approach (

22–

25). Traumatic events often represent a loss or lack of power; therefore, practicing trauma-informed care means empowering the patient in the context of care and being aware of power dynamics between patient and provider (

9). The process of healing can be facilitated when patients feel a sense of agency or control over their treatment (

26). Empowerment entails acknowledging and using patients’ strengths early in the treatment process rather than overemphasizing diagnoses, weaknesses, or victim status. Being trustworthy includes communicating clear and realistic expectations of the treatment process and following through on commitments. Fostering patient autonomy through choice in treatment options is also a critical feature of trauma-informed care. Patients and psychiatrists should be collaborators in care and should engage in additional trauma-informed collaboration with other medical professionals, therapists, support staff, community, and family members when appropriate.

Safety as a core principle of trauma-informed care has multiple valences. Mutual respect is key to a patient’s feeling of emotional and psychological safety. Safety can also be promoted by ensuring the physical environment does not leave the patient feeling vulnerable or trapped. Trauma can be generated not only by the illness experience but by treatment processes themselves; these processes include hospitalization; involuntary treatment such as use of quiet rooms or chemical and physical restraints; adverse effects of pharmacological, somatic, and psychotherapies; exposure to narratives of individuals who have experienced significant trauma; or witnessing aberrant behaviors from individuals who are violent, disorganized, or hurting themselves. Because some patients may have been traumatized by such situations, and because environments can mirror those of previous traumatic events or imbalances of power, discrimination, or lack of identity affirmation, the treatment setting itself should be moderated to avoid a traumatic stress response (

27). Thus, a trauma-informed care approach to the context of care is warranted in all settings: crisis, inpatient, residential, and outpatient. This includes shaping the environment (lighting, the way in which a space is set up), processes (the structure of an appointment or a system of care), and the attitudes and behavior of the practitioner and support staff (i.e., body language, tone of voice, communication skills). The number, gender, and diversity of caregivers and support staff, as well as the ease of communication and coordination between them, can also affect how safe patients feel in the encounter (

28).

A trauma-informed care model is encouraged as a standard of care across health professions and settings, regardless of whether a given patient has reported or experienced trauma and without requiring providers to know whether a specific patient has a trauma history (

22,

27). Taking universal trauma precautions establishes safety and attunement with trauma survivors, is consistent with person-centered care (

23), and may be especially relevant for minoritized community members.

Cultural Contexts of Trauma and Trauma-Informed Care

Hand in hand with the trauma-informed care principle of the uniqueness of individual experience goes the variability of race, culture, ethnicity, nationality, and socioeconomic status (

1,

10,

29–

31). It is through and within a cultural frame that people construct their realities, meanings, and identities (

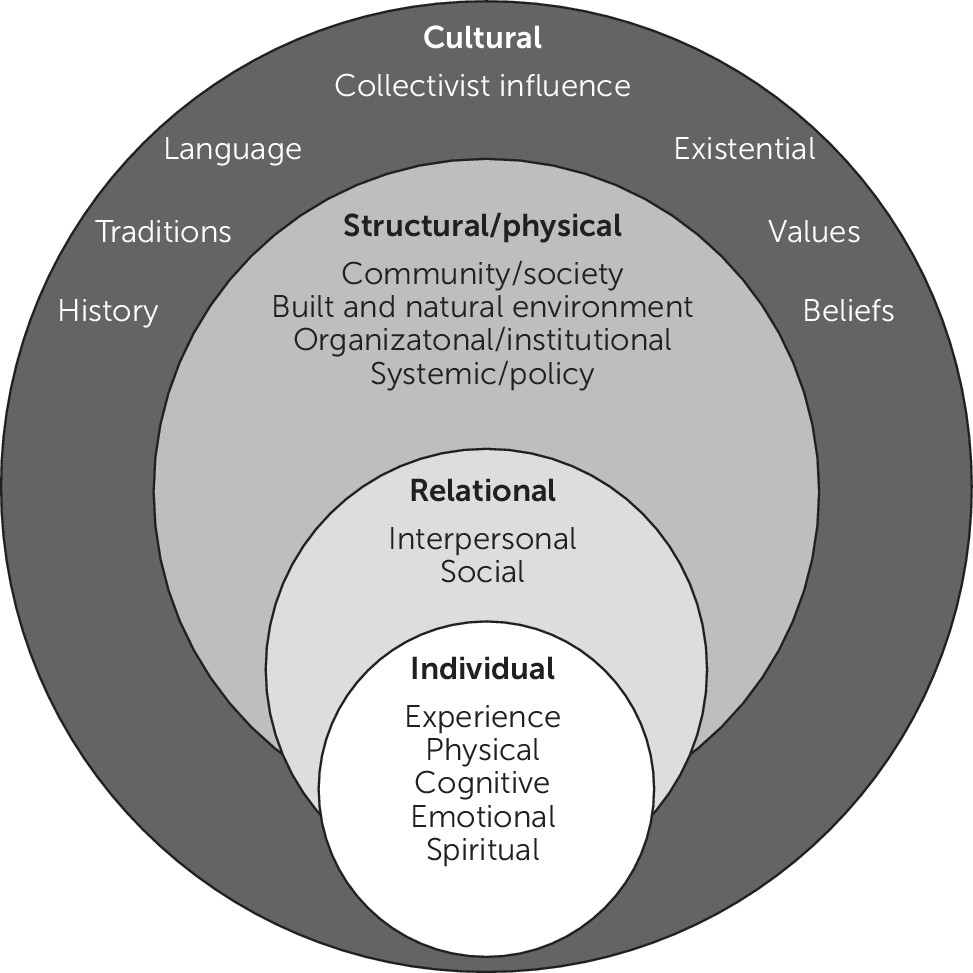

32), as illustrated in

Figure 1.

Trauma is not experienced independently of cultural context, and cultural and societal configurations influence—and sometimes cause—trauma. As an example, racial trauma, a form of race-based stress, has been reported to result from experiences of racial discrimination such as workplace incidents or hate crimes, or it can be the result of an accumulation of many small occurrences, such as everyday exclusion and microaggressions (

10). Existing in an intersectional relationship with race and ethnicity are gender, sexuality, and sexual identity, among others, which may also affect one’s risk for and experience of trauma (

33). Historical trauma, defined by Maria Yellow Horse Brave Heart as “cumulative emotional and psychological wounding over the lifespan and across generations, emanating from massive group trauma,” affects many, including native populations who have endured severe losses, whose lands have been colonized, and whose traditions have been subject to forcible eradication (

34,

35).

Although some patient populations may be more susceptible to trauma exposure on the basis of sociodemographic circumstances, culture is one of the mitigating factors that play a role in the variability of individual response to potentially traumatic events (

10–

12). One example of how cultural context can affect a patient’s experience of mental health care is the perception among some African Americans that the health care system as a whole is a white, racist institution (

28). This attitude is sometimes based on personal experiences or family memories, and certainly there is a history of harmful racism in health care in the United States, such as the infamous Tuskegee syphilis experiment. The case of Henrietta Lacks also highlights ways in which standards of patient consent and privacy have been ignored for African Americans (

36). One study found that some African-American patients with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) did not seek treatment because they feared family or cultural disapproval (

37). The myth of the strong black woman might also lead African-American women to avoid seeking care for mental health issues, including trauma (

28).

At the same time, high resilience has been measured among predominantly African-American, trauma-exposed, inner-city patients (

38). African-American cultural aspects that might bolster resilience and thus contribute to healing or moderate the effects of trauma include family cohesion (

39). Strong spiritual or church-based traditions among African Americans can either buffer trauma or serve as a barrier to seeking treatment because the church may be viewed as sufficient for dealing with problems (

37). All of this underscores a complex interplay among causes, individual biology, psychological resilience, cultural context, and social supports in the experience of trauma. Patients bring all these to the clinical encounter.

Physicians also do not come from a neutral position but rather must navigate self-awareness of their own culture, personal history, and implicit biases to better understand patients’ needs and enhance their capacity to promote healing. Rather than operating from the assumption that patients need special treatment because they come from a given culture or social context, physicians should consider that patients’ culture may serve as a source of strength and resources for healing.

Pepe

Pepe is a 14-year-old American Indian boy from a remote reservation. On his father’s side, there are several generations of well-respected traditional healers, although after boarding school acculturation his grandfather and father both struggled for decades with alcoholism and diabetes and then died young. At age 13, Pepe was expelled from school because of behavioral problems. He felt immense shame for being a failure, started to have severe anger outbursts, and later was arrested for punching a 12-year-old in the face after a bullying incident. As a result of suicidal statements he made to police officers during the arrest, he was taken to an inpatient psychiatric unit. There he was noted to be responding to internal stimuli, diagnosed with a psychotic disorder, and placed on antipsychotic medications. When he was discharged home, a local healer explained Pepe’s condition as a spiritual crisis that had the potential to bring great healing to his family and people and, with the right combination of ceremonies and support, could signal his own initiation as a traditional healer, walking in the footsteps of his great-grandfather, who had supported the healing of thousands of people of his tribe.

Pepe’s case exemplifies the way in which one’s particular culture may be a resource for healing. The institutional response to Pepe’s symptoms was to place him on medication, to treat his behavior and response to internal stimuli as a problem to be eradicated. The healer from his tribe was able to reframe the situation as a crisis that could mark a transition into a productive role in the community. Rather than seeing Pepe as someone who needed to be fixed, the healer responded to him as someone who could be guided on a journey to a bright future. Such a positive approach, orienting Pepe toward a goal and toward serving an important function among his people, holds more promise and may well be more effective than medication alone.

Working with traumatized families in a diversified social context is fraught with challenges for the clinician trained and operating in the current Western health care system. The modern Western approach favors an individualizing attitude toward trauma, based on assumptions that individuals conceive of themselves as independent beings. This is a tasking endeavor for most patients who present from collectivist high-context cultures in which a sense of and belief in community and interdependence is promoted, rather than independence, and who hence have more relational self-constructs (

40,

41).

Sara

Sara is 52-year-old refugee who came to the United States after fleeing the war in Iraq. As a child, Sara survived repeated sexual abuse by a relative as well as by a schoolteacher. She also survived physical abuse by her father and, as an adult, sexual, physical, and verbal abuse by her husband. In addition, she experienced food insecurity and hunger with her children during the US sanctions on Iraq and was exposed to war trauma during the Iran-Iraq wars, as well as during the US invasion of Iraq. Sara struggled with chronic bodily pains that could be traced to no organic basis despite an extensive medical work-up and had fainting spells and auditory and visual hallucinations. For example, she would see a man coming into her room whenever she slept with the door closed. Despite perpetual and severe life adversity, Sara did not have symptoms that met DSM-5 diagnostic criteria for PTSD. She also did not meet criteria for a psychotic or a mood disorder. Her doctors attempted treatment with trials of medication from nearly every class of psychopharmacological agents, including antidepressants, antiepileptics, antipsychotics, and anxiolytics, with little benefit. She refused to be seen by a female therapist who shared her cultural background despite strong recommendations. Eventually, the clinical team achieved some meaningful work when they collaborated with interpreters from the same cultural background as Sara and used their services meaningfully as cultural liaisons. Sara did not get a lot better, but she had a relatively good working relationship with her treatment team and consistently showed up to all her appointments.

Unfortunately, as do many patients with complex trauma, Sara posed an added layer of challenge to her clinician because of her atypical presentation, diagnostic complexity, and lack of response to interventions that are considered standard in the modern frame of mental health care. The result was that she had no clear treatment plan, and her needs went unmet. The clinical team, although well-intentioned, treated Sara as an individual separate from her family unit, used the classical outpatient treatment setting, and did not involve her family to understand her cultural background.

Cultural context and conceptualization of self, whether individualistic or collectivist, shape how a person experiences, perceives, makes meaning of, and eventually heals from trauma. These contexts also affect how one’s condition is diagnosed and treated in the health care system. For example, one study looked at a sample of 20 Salvadoran women exposed to trauma and found that 19 did not meet

DSM criteria for PTSD despite their impairment and suffering (

42). In this respect, their cases were similar to Sara’s. In a study that explored variables for resilience and vulnerability after a 1999 earthquake in Turkey, researchers found that participants struggling with trauma did not fit the classical

DSM criteria triad but rather presented with reexperiencing, cognitive impairment, and numbing (

43).

Standards such as the

DSM are not culturally neutral but reflect the cultures within which they were created; they may not align with or account for other ways of understanding or experiences and expressions of trauma (

44). A qualitative study appraising trauma in a focus group of 11 non-Western trauma survivors found that the self was a secondary theme, whereas more relevant, primary themes included social role reversals, fate attributions, and trauma, causing dejection as a result of feeling left out of the group (

45). Researchers elicited poignant narratives of what trauma meant to those in the study. One participant highlighted, “Bonds are everything, so it’s [trauma] something which breaks the family, breaks relationships, breaks your bond to society.” Another said, “In New Year it’s very serious in China…we try to create a [cleansing] environment so for anything bad, when this is finished, all is returned to normal, everything changed . . . so it’s, how to say, closure.” This last example suggests that culture can play a role in therapeutic interventions that are meaningful and opportune. Milestones, rituals, and ceremonies can facilitate or contribute to healing, even if these events or their functioning in this way are unfamiliar in a modern or Western context.

Having established that for many cultures, healing happens collectively, we should note that growing evidence suggests that group therapy has efficacy with trauma patients from collectivist cultures (

46–

49), even though this modality is not standard for treating trauma in the West. Examples of effective results with group therapy include the use of mind-body skills groups with adults and youth in high-stress conflict situations such as Gaza and Kosovo, which produced a significant reduction in PTSD symptoms (

50,

51). A recent comprehensive 2019 Cochrane-style review of therapeutic modalities for refugees diagnosed with PTSD found that group therapy was just as efficacious as individual therapy. The authors of that review thus recommended the use of interventions that are more accessible: “brief, basic,

group and non-specialist–delivered versions of these evidence-based psychosocial treatments” [italics added] (

52).

Cases such as those presented earlier may suggest that to care for patients from a variety of cultural backgrounds, a provider needs to develop an understanding of how the trauma experience manifests itself within the cultural framework and then use interventions that are endogenously healing. However, amassing an understanding of all the cultural contexts one’s patients might come from is a daunting task, and it is complicated by the impossibility of fully understanding a cultural perspective that is not one’s own. For this reason, trauma-informed care can be enhanced by adopting an attitude of cultural humility.

Cultural Humility as an Alternative to Cultural Competence

The lived experience of so many persons involves profoundly disturbing situations such as war, sexual abuse, violence, or racism. These traumatic events are always embedded in a cultural context and identity, and they can result in serious mental and physical health consequences. An adequate approach to healing addresses the intersection of trauma and culture, and psychiatry has sought multiple ways to do so.

Cultural psychiatry provides valuable insights into and a welcome attitude toward the diversity of human experience and how it informs mental health (

53). Others have delineated strategies for equitably oriented health care delivery (

54).

DSM-5 offers concrete tools to facilitate a cultural assessment of the individual, such as the Cultural Formulation Interview (CFI). In this issue of

Focus, Jarvis and colleagues (

55) offer a comprehensive review of the CFI to facilitate practical application. Although the CFI may be helpful as a framework for conceptualization, attempting to be comprehensive in addressing the cultural factors that affect patients’ experience and the practice of psychiatry may be challenging. Physicians should strive to be culturally aware, but problems are inherent in efforts to master multiple cultures, including the colonial or patriarchal mindset or attitude that may accompany such mastery (a telling word) as well as the impossibility of being truly competent in any culture.

Cultural humility is a generic approach to understanding that does not necessarily require a study of what is, in some respects, ineffable: culture as embedded in individuality, biology, personality, and psychology. Rather than approaching embodied, individually experienced culture as something that can be learned, mastered, and neatly categorized, cultural humility entails admitting that cultural experience is something one cannot fully analyze or understand but can seek to appreciate and respect (

56).

Table 1 provides some ways to put cultural humility into practice.

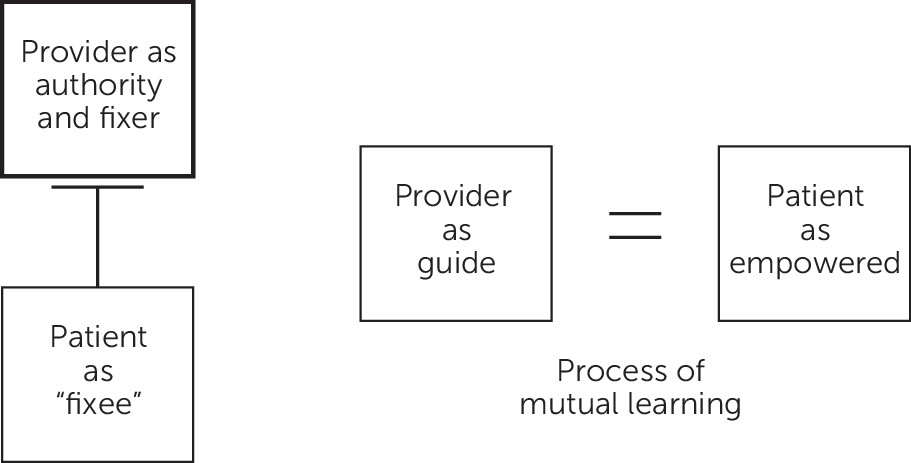

Cultural humility is characterized by principles of mutual learning and critical self-reflection, recognition of power imbalances, and the existence of implicit biases. Its practice can engender respectful partnerships and institutional accountability. In clinical care, cultural humility can serve as a guiding concept for the practice of trauma-informed care in centering and empowering patients on their journey of healing, rather than making assumptions about the patient’s experience or practicing an authoritative, power-over communication style.

Figure 2 illustrates the collaborative nature of trauma-informed care practiced with cultural humility and suggests the mutually beneficial nature of the exchange with such a model.

In the clinical encounter, it is important to consider patients as embedded within a cultural context and to have the humility to learn from patients about resources that their cultural context might contribute to the healing journey. This may necessitate engaging with the family or community leaders, as in the case of Pepe, to integrate cultural resources into the treatment plan or to use cultural liaisons, as in the case of Sara, to begin productive healing work. The variability of individual response to and relationship with one’s cultural background (as well as medical institutions and professionals and traumatic experience) requires abandoning assumptions in favor of an open, humble approach to each case.