Anorexia nervosa (AN) is a costly and deadly mental illness, which is notoriously difficult to treat

1. It is associated with substantial morbidity and mortality, including an elevated suicide rate and an 18-fold increase in mortality

2,3. Despite its seriousness, there are no proven treatments for adult AN that reverse core symptoms and no approved pharmacological interventions

1. As a result, estimates suggest that less than half of patients achieve recovery; relapse rates approach 50%; and approximately 20% of those with AN will develop a chronic course

3. There have been minimal advancements in novel treatment strategies and stagnant outcomes over the past several decades, resulting in a ‘crisis in care’

4,5. Novel and innovative treatments methods are urgently needed to improve treatment engagement and outcomes. One such avenue may be psilocybin therapy.

Psilocybin is a psychedelic molecule whose mechanism of action is thought to be mediated by serotonin 2A (5-HT

2A)

6 and is the main psychoactive compound in the

Psilocybe genus of mushrooms

7. Considerable evidence suggests that individuals with AN have altered brain serotonin (5-HT) function, altered function of the 5-HT

2A receptor and altered endogenous brain 5-HT secretion

8,9, supporting the speculation that the 5-HT

2A effects of psilocybin might effect change in AN symptoms. Unlike other serotonergic medications requiring repeated administrations, a single dose of psilocybin may lead to rapid and enduring synaptic adaptations that have the potential to improve AN symptoms

10. However, the role of 5-HT dysfunction in AN and related affective states associated with restriction remains poorly understood with mixed findings

11,12.

Mechanisms of action are not well elucidated, but psilocybin is thought to directly modulate the serotonergic system and indirectly modulate dopaminergic and glutamatergic systems and gene expression

10. Psilocybin effects have been documented at the pharmacological, neural and psychological levels, all of which may contribute to improvements in mental illness

13. Findings suggest that psilocybin may increase emotional and brain network plasticity, which may be responsible for sustained improvements in mental health status

14. Psilocybin therapy typically involves the administration of psilocybin in conjunction with psychological support delivered by one to two trained therapists

15. When administered in a safe and therapeutic setting in conjunction with psychological support, participants can report transformative experiences characterized by profound changes in values, beliefs and perspectives, which can lead to positive changes in subjective well-being, increased openness and greater cognitive flexibility

16–18. Available evidence suggests that psilocybin therapy may hold promise for other treatment-resistant mental illnesses with studies demonstrating robust and rapid effects, but no modern studies have reported data on potential effects for AN

19.

AN is characterized by excessive and undue preoccupation, fear and distress surrounding food, weight, shape and eating. This typically leads to rigid and repetitive behavioral patterns of control, such as restriction

20. Improvements in anxiety

21 and cognitive flexibility

18,22, which have been shown to occur with psilocybin therapy, may assist with disrupting cardinal symptoms of AN mediated by these mechanisms, including eating disorder (ED)-related preoccupations, rigid thinking styles and entrenched behavioral patterns

23,24. AN is often ego-syntonic in nature

25, and AN behaviors are perceived as effective means to achieve internalized weight/shape ideals and avoid dysphoric mood states that result from eating

9. Thus, individuals with AN may resist intervention or fail to acknowledge the seriousness of the illness, resulting in low treatment acceptability and substantial treatment dropout

26. Psilocybin therapy, which has been shown to improve openness

27 and occasion transformative experiences

17, may facilitate a re-organization of values, shifting the relative importance of shape and weight and/or induce greater permeability to new attitudes and behaviors by directly targeting these features. Previous observational and naturalistic studies exploring the value of psilocybin and other psychedelic drugs in people with EDs have reported on emerging themes, such as increased affective and intellectual awareness, reduction in ED symptoms, positive mood changes, emotional processing and increases in self-acceptance

28–30.

To date, no modern publications have reported data regarding the safety, tolerability and efficacy of psilocybin therapy for AN within the context of a clinical intervention; however, at the time of this publication, two additional registered clinical trials are currently underway (NCT04505189 and NCT04052568), and other ED expert groups have provided rationales for further evaluation of psychedelic treatments for AN

31,32.

To our knowledge, the present study is the first modern trial to report data on the safety, tolerability and exploratory efficacy of a single 25-mg dose of psilocybin in conjunction with psychological support.

Results

Patient Information

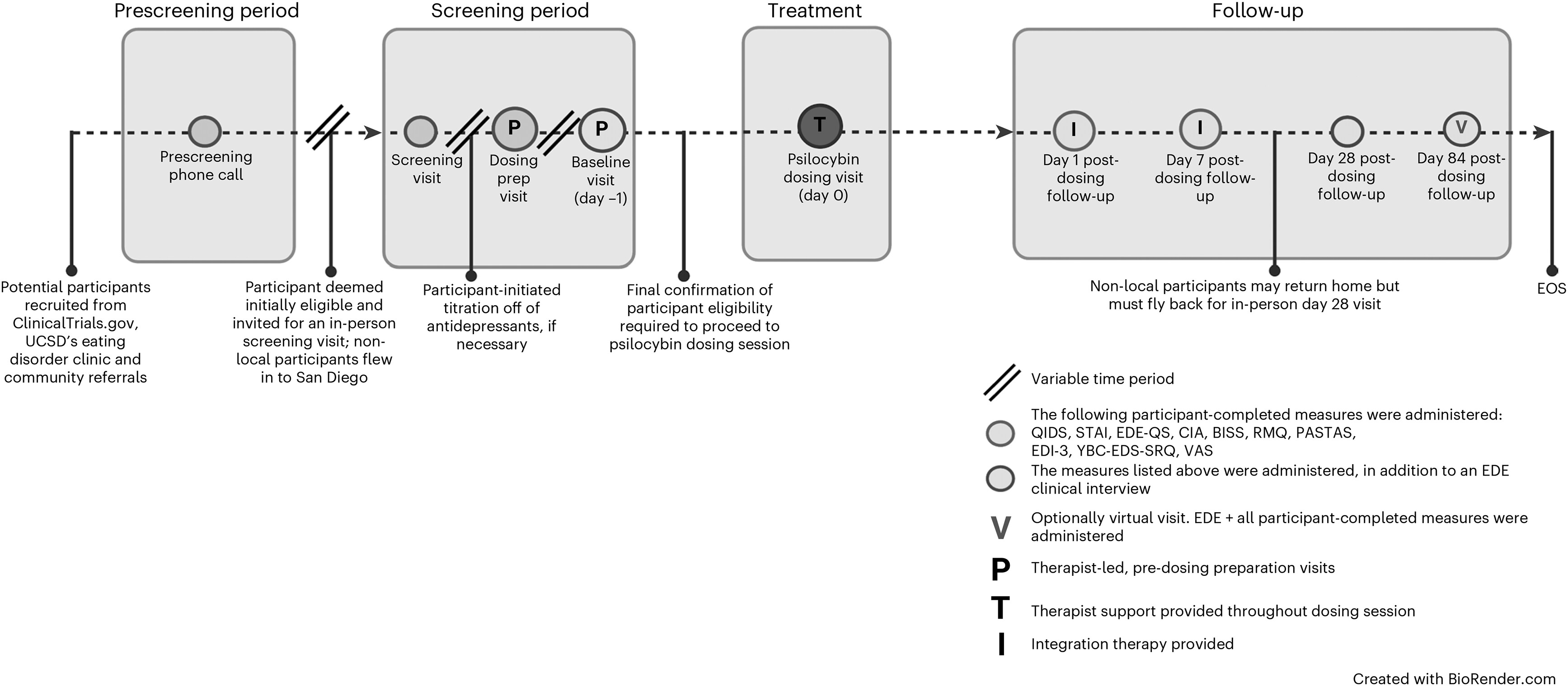

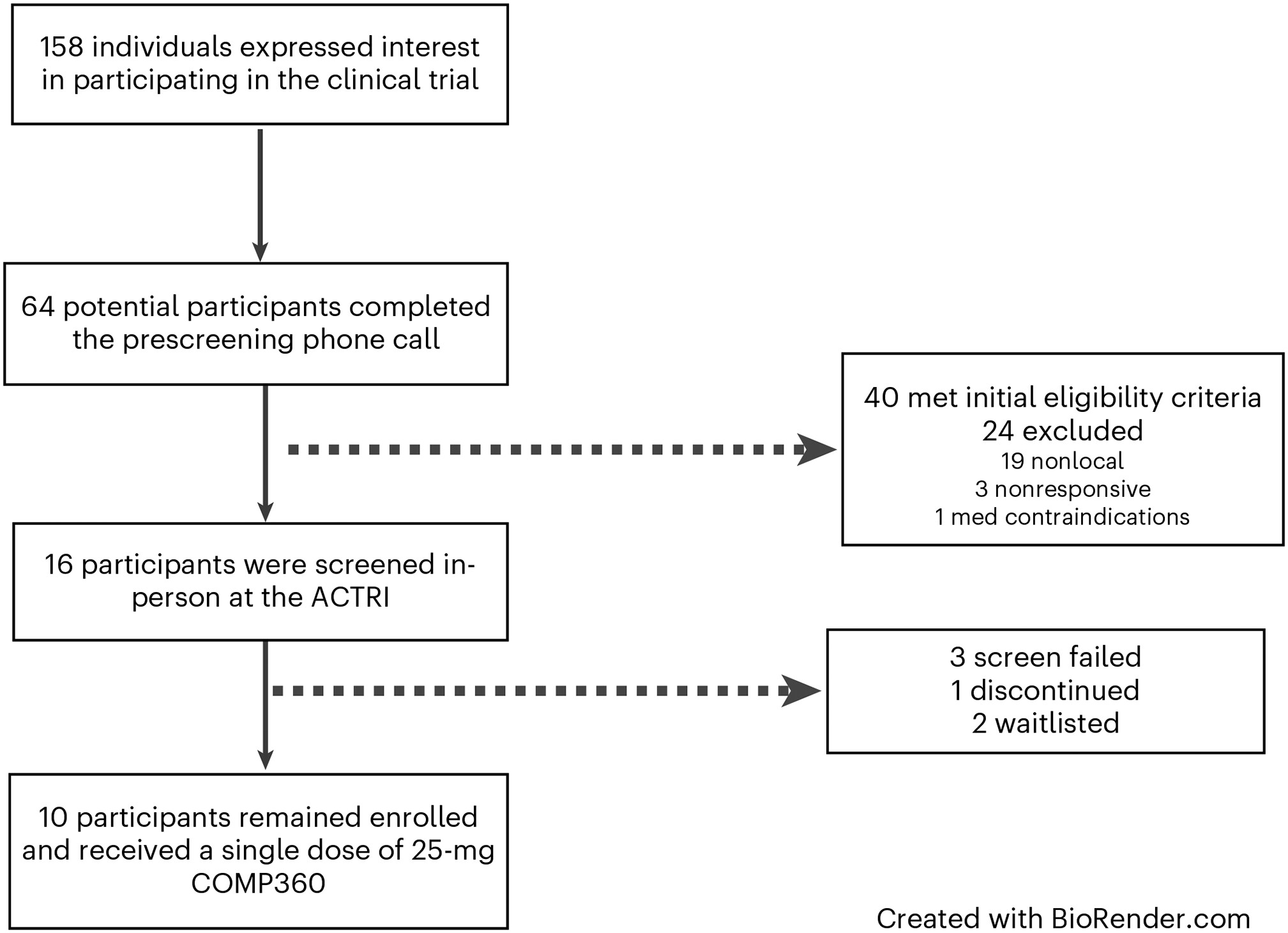

Enrollment started in April 2021 and finished in December 2021. In total, 158 individuals expressed interest in participating. Most were self-referred and became familiar with the study via ClinicalTrials.gov (ClinicalTrials.gov identifier: NCT04661514) or through community providers familiar with the study through community outreach efforts (see

Table 1 for sample demographics,

Figure 1 for study design and timeline, and

Figure 2 for participant flowchart).

Primary Outcomes: Safety and Tolerability

To evaluate safety, we examined changes in vital signs, electrocardiograms (ECGs), clinical laboratory tests and suicidality from baseline (day −1) to day 1 (

Table 2) and 1-week follow-up; we also examined reports of adverse events (AEs). The acute effects of psilocybin were well tolerated by all participants, and no serious AEs were observed (

Table 2). No clinically significant changes were observed in vital signs or ECG. In relation to clinical laboratory values, two participants, both of whom were required to eat breakfast at the clinic before administration, developed hypoglycemia in follow-up clinical laboratory assessments, which resolved within 24 h. Participants were asymptomatic, and no intervention was required. No other clinically significant changes were observed in laboratory values. Suicidality was assessed using the Columbia Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS)

33 at each timepoint. There were no increases in suicidal ideation (SI), and no suicidal behaviors were present in the post-dosing follow-up visits. One participant with a history of major depressive disorder (MDD) and SI reported an increase in SI at 3-month follow-up, which did not appear related to study participation. AEs (

Table 2) were mild and transient in nature, with headache, nausea and fatigue being the most common.

Secondary Outcomes: Changes in Psychopathology

Average changes on Eating Disorder Examination (EDE) subscales are shown in

Table 3. Results from

t-tests indicated that weight concerns decreased significantly from baseline (day −1) to 1-month (

P=0.036, Cohenʼs

d=0.78) and 3-month (

P=0.04,

d=0.78) follow-up, with a medium to large effect. Shape concerns significantly decreased at 1-month follow-up (

P=0.036,

d=0.78) but were no longer significant at 3-month follow-up (

P=0.081,

d=0.62). Changes on the eating concern and dietary restraint subscales were not significant, but changes in eating concerns approached significance at 3-month follow-up (

P=0.051,

d=0.71). Effects of treatment were, however, highly variable among participants, as is illustrated from the case series data (Extended Data Figure 1). Four participants (40% of sample) demonstrated global EDE scores that decreased to within 1 s.d. of community norms (mean 0.93, s.d. 0.80)

34 at 3-month follow-up (Extended Data Figure 2), which we interpret to be clinically significant. No correlations were observed between any assessed participant characteristics and outcomes. Three of four responders met criteria for AN (versus pAN), and one had a diagnosis of anorexia nervosa binge–purge (AN-BP).

Body mass index.

On average, changes in body mass index (BMI) were not statistically significant (see Extended Data Tables 2 and 3 for mean BMI scores over time and BMI changes over time for each participant). Of the four participants who demonstrated clinically significant reductions in eating disorder pathology as measured by the EDE, changes in BMI were variable, and there was no correlation between outcomes and weight status. Five participants demonstrated an increase in BMI at 3-month follow-up (range, 0.4–1.2 kg m−2).

Other secondary measures of psychopathology.

Results for other secondary measures were also highly variable among participants. On average, participants demonstrated significant reductions at the primary endpoint of 1-month follow-up across the following domains: trait body image anxiety (Physical Appearance State and Trait Anxiety Scale (PASTAS)) (P=0.04, d=0.76), trait anxiety (Spielberger State-Trait Anxiety Inventory (STAI-T)) (P=0.036, d=0.78) and preoccupations and rituals surrounding food, eating and shape (Yale-Brown-Cornell Eating Disorder Scale (YBC-EDS)) (P=0.043, d=0.75) (Extended Data Tables 2 and 4).

Exploratory Outcomes: Changes in Psychopathology

Patient experience and acceptability.

Qualitative responses highlighting participants’ reports of impactfulness are summarized in

Table 4. Overall, the psilocybin experience was regarded as meaningful by participants. Ninety percent endorsed feeling more positive about life endeavors; 80% endorsed the experience as one of the top five most meaningful of life; and 70% reported experiencing a shift in per-sonal identity and overall quality of life. Notably, 90% of participants reported that one dosing session was not enough. Phenomenological and qualitative information related to participants’ experience will be presented in a forthcoming manuscript.

Response to psilocybin.

Average self-reported intensity of the experience using the 11 subscales of the Five-Dimensional Altered States of Consciousness (5D-ASC) questionnaire is reported in Extended Data Figure 3. No participants required anxiolytic rescue medication during the dosing session.

Exploratory measures of psychopathology.

We also explored changes in depression scores (Quick Inventory of Depressive Symptomatology (QIDS)), functional impairment related to ED psychopathology (Clinical Impairment Assessment (CIA)) and readiness and motivation to change (Readiness Motivation Questionnaire (RMQ)) at 1-month follow-up. Results are presented in Extended Data Table 5. Results from t-tests indicated that functional impairment related to disordered eating as measured by the CIA decreased significantly from baseline (day −1) to 1 month (P=0.041, d=0.75). Other changes measured were not statistically significant.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first data report on the effects of psilocybin therapy in AN in a clinical research trial. This open-label pilot study examined the safety and tolerability of administering psilocybin therapy to participants with AN and pAN. We chose to include participants in partial remission because we were most interested in exploring potential changes in core ED psychopathology (versus weight), which can lead to treatment resistance and which can persist after weight restoration

35. Additionally, pAN has been shown to be common, severe, persistent and undertreated

3,35.

Psilocybin therapy, which includes psychological support by trained therapists, was found to be safe and well tolerated for the 10 participants who received treatment in this study. Most participants endorsed the treatment as highly meaningful and the experience as a positive life impact, and yet effects on ED psychopathology were highly variable, with a subset of participants demonstrating a robust response for a single-dose treatment. Results of this study are preliminary and inconclusive given its size and design. In this section, we discuss study findings related to primary outcomes, patient acceptability and qualitative perceptions as well as ED-specific psychopathology.

No participants in our study experienced any serious AEs, and all treatment-emergent AEs resolved within 24 h and without intervention (with the exception of one report of orthostatic heart rate that was reported at 3-month follow-up for one participant). Hypoglycemia occurred in two participants on the dosing day and resolved in 24 h. We hypothesize that this was related to a prolonged period of fasting on the dosing day (a common effect of psilocybin) versus any direct relationship to the drug, given the state of malnutrition and low carbohydrate stores associated with AN. Food was available on request to participants during the dosing day, but participants were not required to eat during the therapeutic experience. To our knowledge, there are no reports of psilocybin-induced hypogylcemia. However, individuals with AN often have reduced plasma glucose levels

36. The incidence of hypoglycemia is clinically important and may indicate that attention to blood glucose levels before and after intervention may be warranted in participants with compromised nutritional status given the dangers associated with hypoglycemia in AN, including sudden death

36. Both incidents of hypoglycemia occurred in participants who were given a standardized breakfast upon arrival. AN has a high prevalence of serious medical complications and physiological disturbances, which account for much illness-related death. The lack of negative incidences regarding safety in our study is promising for future research with the AN population; however, larger studies with a more diverse participant group continue to be needed to determine safety

37.

Most participants self-reported positive changes 3 months after the psilocybin dosing. That the treatment was regarded as beneficial by most participants and that there were no dropouts are promising signs of engagement. Dropout rates in currently available treatments tend to be high

38. Positive patient perceptions are also notable because they may suggest improved quality of life, which is clinically important for those with a potentially severe and enduring illness

38. These self-reported data suggest that most participants perceived some benefit that may have been ED-non-specific in nature or not well captured by our assessment measures. Although our treatment included AN-specific therapeutic elements, adjunctive therapy was brief. Additional therapeutic methods, or extended therapeutic time, may be a useful consideration to facilitate further behavioral change and increased specificity, as has been employed in other psilocybin studies

39,40. Our effect sizes and response rates were less robust than those reported for primary outcomes in psilocybin studies for other psychiatric disorders

41–43. This may also be related to a heterogenous sample, a single-dose trial (compared to a two-dose design used in other studies), a lack of sensitivity in assessment measures or unique/specific features of AN that are not as readily addressed by psilocybin therapy or that require dosing adjustments. AN is a difficult-to-treat disorder with a complex physiology and physical recovery needs that differentiate it from other mental illnesses. Notably, 90% of participants reported that one dosing session was not enough, suggesting that an additional psilocybin experience(s) may be beneficial

44.

Our exploratory analysis showed some significant reductions in ED-related psychopathology when the sample was aggregated; however, the results were highly variable among participants. Forty percent (4/10) of participants demonstrated clinically significant reductions

34 in ED psychopathology (EDE) at 3-month follow-up, with scores decreasing from clinical ranges to within 1 s.d. of community normative values

34. Within the responder group, ED psychopathology decreased precipitously and dropped below clinical levels within the month after the psilocybin dosing session. Three of the responders were not enrolled in any concurrent mental health services during the study period but had mental health treatment histories, and one was in longstanding, outpatient therapy that did not change during study enrollment. Symptoms continued to improve between 1-month and 3-month follow-up. Given the size and design of this study, these effects are preliminary and inconclusive. However, it is notable that we found such a robust response in a subset of participants in a single-dose trial of psilocybin delivered over a brief time period, because currently available treatments for adult AN result in only modest improvements in symptoms and often focus on weight and nutritional rehabilitation without adequately addressing underlying psychopathology

38. Participants also experienced significant reductions in anxiety; however, mean changes in depression scores were not significant. Changes in general psychopathology may partially explain the effects on ED symptoms

44.

We did not observe a significant effect on BMI over time, and results were highly variable among participants. BMI did not follow the same change trajectory as ED psychopathology for participants who showed reductions on core psychopathology. Of the four treatment responders, two showed positive BMI trends, one remained stable at a normal BMI and one showed a two-point decrease over time. It is also possible that a longer follow-up period is necessary to observe meaningful changes in BMI, which has been suggested by ED experts

45,46. Notably, there are well-documented phenomena associated with AN that impede upon weight rehabilitation, including hypermetabolism and unusually high caloric requirements

37. When queried about the lack of weight change, one treatment responder stated, ‘The irony is that now that I want to recover I can eat intuitively, but that is not enough to support physical recovery’. These findings may suggest that targeted nutritional rehabilitation emblematic of traditional treatment may be a necessary adjunctive treatment even when significant improvements in ED psychopathology are conferred.

Limitations of this study include its small sample size, the lack of a control comparison and the open-label design. Owing to the exploratory nature of this study, we did not conduct a power analysis or correct for multiple comparisons. As a result, these findings are not conclusive and should be interpreted with caution. Additionally, all of the participants were self-referred, which may have resulted in a selection bias. Similarly, suggestibility and expectations of positive outcomes related to positive popular media coverage surrounding psychedelics, and attending treatment at a well-reputed ED service (particularly for those who were nonlocal), may have resulted in a suggestibility that influenced positive outcomes. Our sample included a diverse range of severity; however, many participants had mild to moderate AN. More research is needed to evaluate psilocybin therapy for severe presentations. The study also lacked gender, racial and cultural diversity.

Strengths of this study included administration of a precise dose of pure synthesized psilocybin and the evaluation of a highly novel treatment modality for a treatment-resistant population. Larger, adequately powered, well-controlled trials with comparator treatments are needed to evaluate the efficacy of psilocybin therapy in a diverse sample of patients with AN. Future studies should further investigate mechanisms of action and moderators of treatment to discern how psilocybin may lead to changes in AN and whether psilocybin therapy is more suitable and effective for a specific subset of AN. Additionally, future studies are needed for optimization to identify adequate dosage, identify the optimal number of psilocybin administrations and investigate the need for possible adjunctive treatments that could optimize treatment outcomes.

In conclusion, results from this open-label, single-arm study suggest that psilocybin therapy is safe and tolerable in participants with AN; however, adequately powered, randomized controlled trials are needed to draw any conclusions.

Online Content

Any methods, additional references, Nature Portfolio reporting summaries, source data, extended data, supplementary information, acknowledgements, peer review information; details of author contributions and competing interests; and statements of data and code availability are available at

https://doi.org/10.1038/s41591-023-02455-9.