Background

Young people present with the highest prevalence of mental health disorders compared to individuals at any other stage of the lifecycle [

1], with up to 20% of adolescents likely to experience mental health disorders [

2]. Mental health has been defined as “a state of wellbeing in which and individual realizes of his/her abilities, can cope with normal stresses of life ( …) and is able to make a contribution to his/her community” [

3]. Around 50% of mental health conditions start before the age of 14 [

4] and the onset of 75% of cases is before the age of 18 [

5]. The most common diagnoses are depression and anxiety [

6] and around 25% of young people experience psychological distress [

7]. Depression is one of the principal causes of illness and disability in teenagers, and suicide is the third most common cause of death among older adolescents [

4]. Mental health problems can significantly affect the development of children and young people [

4] having an enduring impact on their health and social functioning in adulthood [

8]. Adolescents experiencing mental health conditions may face several challenges such as isolation, stigma, discrimination and difficulty in accessing health services [

2]. However, 75% of adolescents with mental health problems are not in contact with mental health services [

9], the primary reason being reluctance to seek help [

1,

10,

11].

Help-seeking for mental health problems necessitates communicating the need for personal and psychological assistance to obtain advice and support. Rickwood and Thomas’ (2012) define help-seeking for mental health problems as “an adaptive coping process that is the attempt to obtain external assistance to deal with mental health concerns” [p. 180,

12]. This includes both formal (e.g., health services) and informal (e.g., friends and family) sources of help. However, adolescents most in need of psychological help are those least likely to look for it [

1–

13]. One of the biggest challenges in adolescent mental health is ensuring that at-risk individuals are linked with the appropriate support [

14]. Understanding barriers and facilitators to help-seeking is fundamental for the development of interventions and programmes to support adolescents with mental health problems.

Rickwood et al., (2005), investigated the main barriers and facilitators of help-seeking for mental health problems in young people. They found that lack of emotional competence, negative beliefs about help-seeking and stigma were the most prominent barriers. Conversely, emotional competence, previous positive experiences with health professionals and mental health literacy, were the main facilitators [

15]. Gulliver et al., (2010) performed a systematic review of the available literature at that time, finding similar results; however, they stated that stigma was the most prominent barrier for seeking for help in young people [

1]. Another systematic review was made by Rowe et al., (2014), focused on in help-seeking for adolescent self-harm. They found that in addition to stigma, negative reactions from others related to confidentiality breaches and being seen as an “attention seeker” were the most relevant obstacles [

10]. While interesting, these previous reviews do not address the help-seeking barriers and facilitators of most common mental health troubles among adolescents, nor include interventions targeting these. Rickwood, Deane et al., (2005) only included depressive symptoms, personal emotional problems and suicidal thoughts and Rowe et al. (2014), only focused on adolescent self-harm. The most complete review published by Gulliver and colleagues (2010) is almost 10 years old and need of updating.

Adequate and effective interventions that promote help-seeking are necessary for enhancing prevention, early detection, timely treatment and recovery from mental health problems [

14]. Previous systematic reviews on interventions targeting help-seeking reveal some promising results in regard to enhancing mental health literacy [

16] and a significant positive overall effect of these interventions in improving help-seeking for mental health problems [

17]. Nonetheless, these reviews do not focus on adolescent populations and only one includes randomised controlled trials (RCT).

The primary aim of this review is therefore to provide an update of the literature on barriers and facilitators of adolescent mental health help-seeking including formal and informal sources of help, with the inclusion of interventions targeted at improving this. We will focus on common mental health problems, including depression, anxiety, suicidal thoughts, self-harm, emotional distress, among other personal-emotional symptoms. The secondary outcome is to examine any significant differences between age and sex. Understanding the difficulties around help-seeking behaviours and facilitating access to timely and effective treatment is essential for preventing the escalation of mental health problems among adolescents.

Methods

For the purpose of this review, help-seeking was defined as the action of actively searching for help for mental health problems, including informal (family, friends) or formal (GP, mental health professionals, etc.) sources, based on interpersonal and social abilities [

11]. “Adolescents” were people aged 10 to 19 years, as defined by the World Health Organisation [

4]. Despite the increasing debate regarding the age of adolescence [

18], this definition was considered as appropriate for our study as it is accepted by international organisation such as OMS and UNICEF. Also, we considered this age range more homogenous and comparable in terms of lifecycle experiences and challenges that would be reflected in help-seeking behaviours and intentions. This review was prospectively registered on PROSPERO (CRD42018096917) and reported in accordance with the PRISMA guidelines [

19]. The search terms were developed using the PICO structure, then expanded using MeSH terms and combined using Boolean operators. Four databases were selected including MEDLINE®, Embase, PsycINFO, and Web of Science, as well as the search engine Google scholar, identified as an optimal database combination [

20]. Grey literature from the mentioned databases was also included and a search was carried in Open Grey. An initial version of the proposal for this study was reviewed by the McPin Foundation. The feedback was considered in the developmental stage, in order to evaluate the relevance and reception of the protocol by Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) organisations.

We included studies published in English, Spanish and French and focused on identifying barriers, facilitators and interventions targeting help-seeking behaviours for mental health problems in adolescents, specifically depression, anxiety, suicidal ideation, emotional distress and general symptoms of mental illness. Other mental health problems such as psychosis, anorexia, among others were excluded, because we decided to focus on most prevalent mental health problems which share a more similar help-seeking process. Regarding barriers and facilitators, we included studies published after 2010 since a previous systematic review on the topic was published then [

1]. We did not include any limit regarding year of publication for help-seeking interventions. All study designs were considered, including feasibility studies and study protocols. We excluded studies that referred to young people over the age of 19 or children under 10 years old. When study populations included adolescents outside of the established age range, the paper was included if over 50% of the individuals in the sample were within the 10–19 years category or if separate outcome data was provided for the participants in this age range. Studies meeting the inclusion criteria and including parents in their sample were also considered. Finally, other exclusion criteria were articles written in other languages, or if the intervention did not explicitly target help-seeking behaviours or was not related to mental health conditions (Appendix S1) (

Table 1).

The search was performed in June 2018 and updated in April 2019. The results were exported to EndNote X8 and duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened by one author (AA) at the first stage. At a second stage, two authors (AA and IS) checked the full articles using the pre-determined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A third member of the research team (MJ) was available to solve discrepancies. Disagreement on 12 studies was attributed mainly to differences concerning the definition and measurement of help-seeking and was resolved in a discussion with a third author (MJ) not involved in the process of screening. Authors were contacted when relevant information was missing or when we could not find the articles retrieved by the databases. Reference list of all included studies were screened in case we found other studies relevant to our review. Data were extracted using a predefined form, which allowed the research team to identify the main characteristics of each study. This process was executed by one author (AA) after a complete review of the included papers. For the first question, data extraction focused on identifying barriers and facilitators and for the second question, intervention and effect size when reported. We created an additional form to extract data regarding the secondary outcome (age and sex). For the quality assessment, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute Critical Appraisal Checklist [

21] and the Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) [

22], which were appropriate due to the variety of study designs included in this review; both have been previously validated [

23,

24]. The Joanna Briggs tool has a number of checklists to evaluate the main features of each study design. We used the checklist for cross-sectional studies, RCT, quasi-experimental studies and qualitative studies. Each checklist had a number of items to evaluate the most relevant aspect of the specific design (e.g: for RCT was allocation to treatment groups concealed? Were treatment groups similar at the baseline?). After completing the checklist an overall quality appraisal score was calculated to provide a measure (low, medium and high) of the quality of each study. The MMAT included a similar checklist but is specific to mixed method study reviews. Overall study quality was not used as an exclusion criterion because we opted to be overly inclusive and provide a thorough overview of help-seeking in adolescents. Results have been summarised using a narrative synthesis. We identified the most relevant features regarding help-seeking barriers, facilitators and interventions in our data. These features were grouped into themes that capture the essential aspects regarding the main outcome of this review. With this information we developed a preliminary synthesis of the results organizing the themes so that patterns regarding the main barriers, facilitators and interventions were identified. Finally, we explored previous evidence on the topic and explore the relationship between the included studies. This allowed us to explore the influence of heterogeneity and the robustness of the preliminary synthesis [

25]. Due to the heterogeneous nature of the studies included, a meta-analysis was not conducted. The quality of each study was not used as an exclusion criterion or impacted the weight given to each study in the narrative synthesis. This over-inclusive criteria allowed us to have an overall picture not only regarding help-seeking barriers, facilitators and interventions, but also the methodological quality of the available evidence.

Results

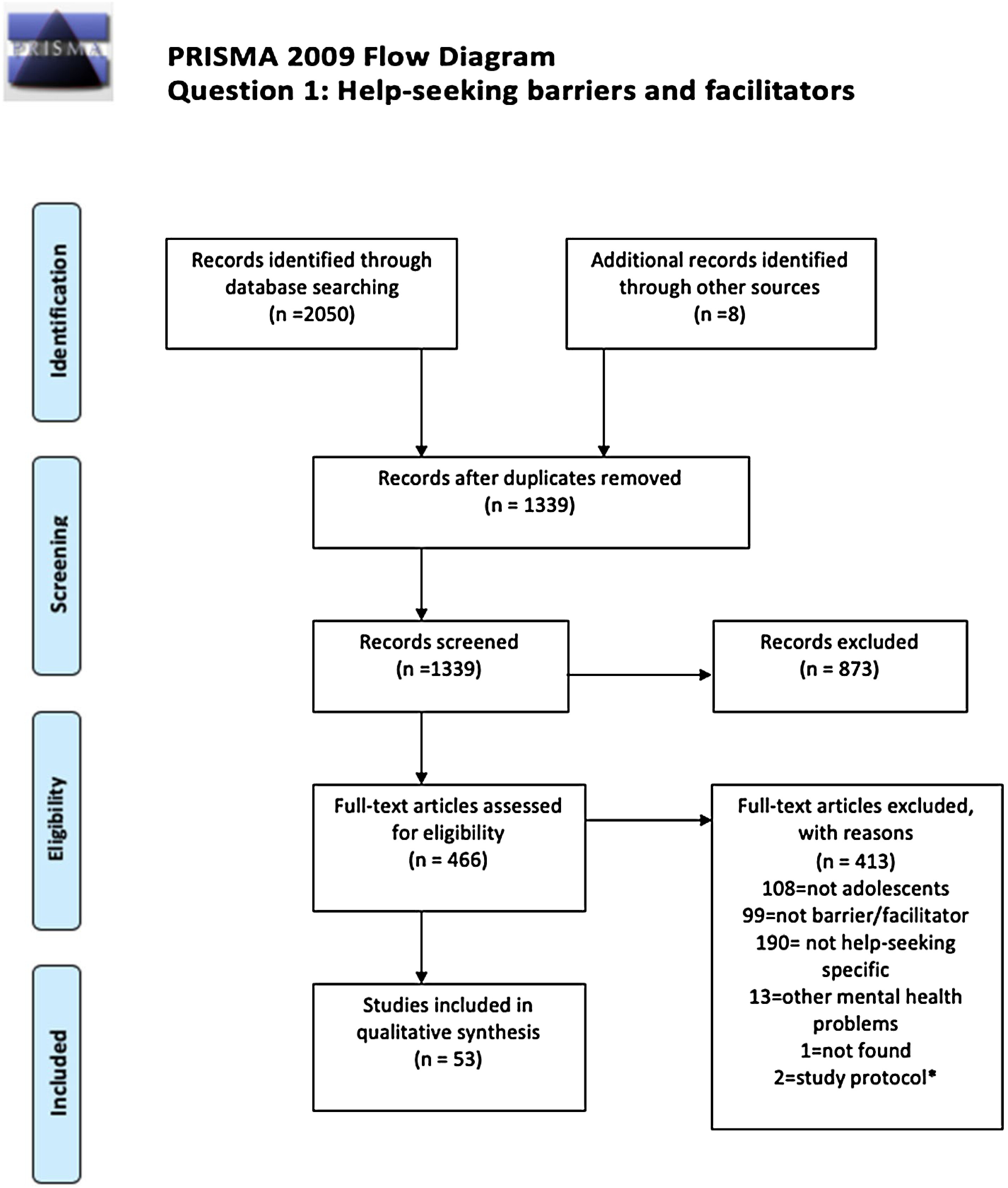

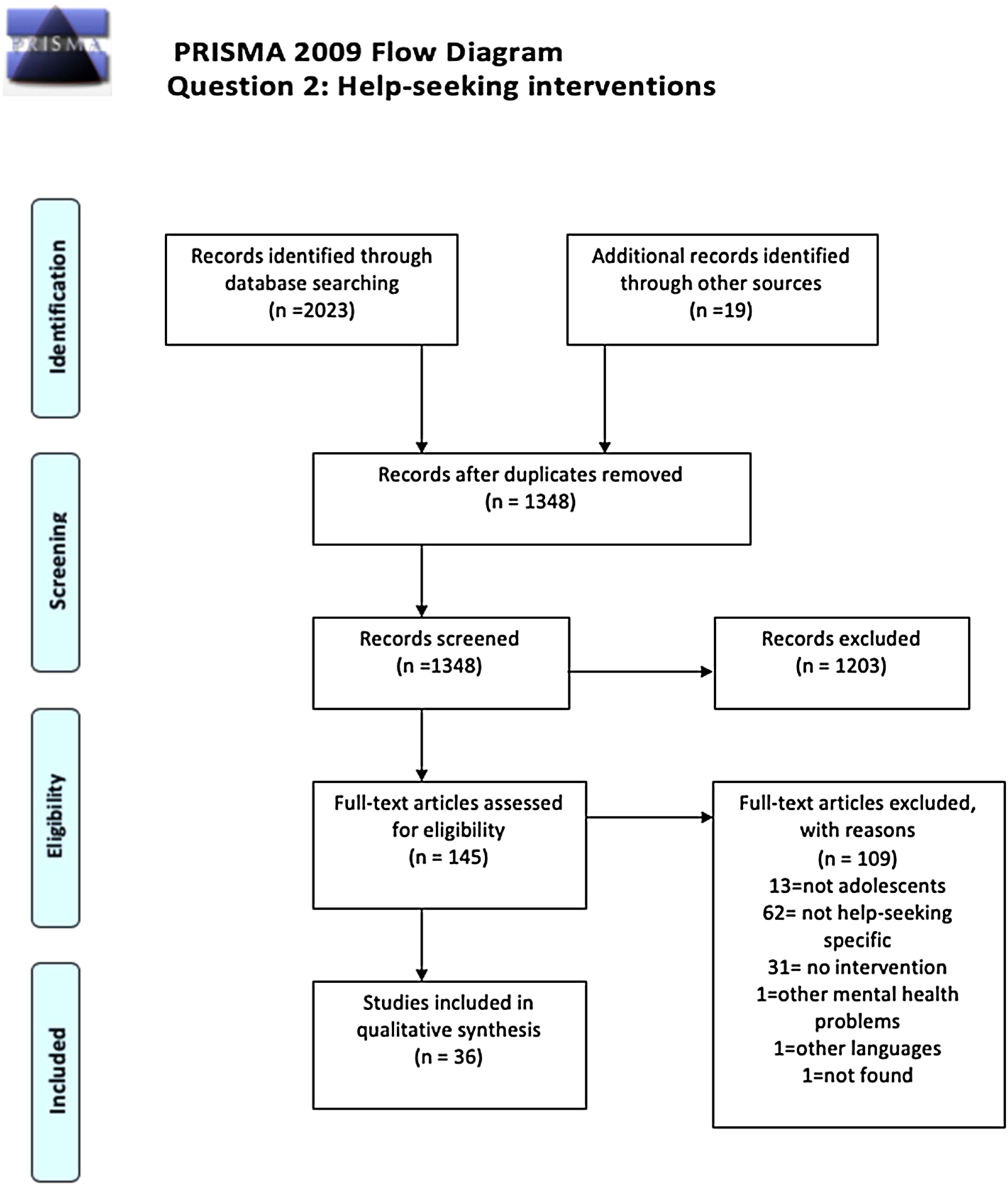

Two independent searches were carried out during June 2018 and then updated in April 2019. A total of 90 studies were included in this review, combining both barriers and facilitators (

n = 54) and the intervention (

n = 36) questions. PRISMA diagrams displaying the number of papers retrieved and the process of selection of the included studies is available in

Figs. 1 and

2. Regarding the inter-rater reliability for this review, the agreement between the researchers screening the papers was high, with a 85% accuracy and 95% precision (Kappa = 0.954). Adolescents identified a range of formal and informal help-seeking options across studies, such as GPS, psychologists, psychiatrists, teachers, social workers (formal), and friends, family, sporting coaches, and online communities (informal). Regarding question 1, most of studies focused on identifying barriers and facilitators towards formal sources of help, whereas intervention studies had a wider variety of sources of help, depending on help-seeking behavior attempted to promote.

Question 1: Help-Seeking Barriers and Facilitators

Fifty-four studies that reported barriers and/or facilitators including a total of 56,821 participants were considered in the narrative synthesis (

Table 2). Most of the studies (

n = 18) were conducted in Australia, followed by the United States (

n = 12) and the United Kingdom (

n = 5). The majority of the studies were cross sectional (

n = 36) [

26–

61], thirteen studies were qualitative [

62–

74] and six used a mixed-method design [

75–

80]. Three PhD dissertations and one conference abstract were included in the grey literature. The age ranged from 8 to 26 years old. Three articles included adolescents and their parents, while one article included just adolescents’ mothers.

The majority of studies were conducted in educational settings, such as schools (n = 24) and tertiary education (n = 11) focusing in non-clinical samples. Sixteen studies included participants from other community settings and two studies were conducted in mental health care facilities. Among the studies that include actual help-seekers (n = 7), the most common reason for seeking help was suicidal ideation, self-harm, depressive symptoms, and general mental health concerns (e.g., anxiety/nervousness/fear). Therefore, the conclusions drawn by the majority of the articles were based on help-seeking intentions rather than actual behaviours, since the participants were not experiencing mental health problems and focused on hypothetical scenarios.

Help-Seeking Barriers

Stigma.

Stigma is defined as the fear of being socially sanctioned or disgraced leading to hiding or preventing certain actions or behaviours, including the misreporting of mental health problems [

81]. More than half of the included studies (

n = 30) made reference to this and other negative attitudes towards mental health problems as the main obstacle to help-seeking behaviours in adolescents. Of these, twenty-five studies referred to stigma as the primary obstacle, describing it through different concepts such as, “stigma”, “fear of stigmatisation”, “community stigma”, “perceived stigma” and “self-stigma”. Other negative attitudes towards mental health problems included shame, fear, and embarrassment.

Family beliefs.

The second most mentioned barrier was associated to adolescents’ family beliefs toward mental health services and treatment (n = 15). Barriers related to problem with communication and distrust towards health professionals, negative past experiences with mental health services, and believing that the treatment is not going to be helpful. This was especially true for studies including immigrant and refugee populations, which referred to cultural barriers including mistrust of mental health diagnosis and practitioners, and lack of cultural sensitivity in services as a significant barrier.

Mental health literacy.

Mental health literacy refers to the ability to use mental health information to recognise, manage and prevent mental health disorders and make informed decisions about help-seeking and professional support [

82]. Almost one-third of the articles (

n = 14) referred to problems related to mental health literacy as a significant barrier including poor recognition of mental health conditions (self and others) and lack of awareness of available sources of help.

Autonomy.

Adolescents’ attitudes towards help-seeking revealed a perceived need of self-sufficiency and autonomy which were recognised as a relevant barrier in twelve studies, as well as fears of confidentiality breaches.

Other help-seeking barriers.

To a lesser extent, problems regarding service and personnel availability and other structural factors (such as cost, transportation and waiting times) were mentioned as obstacles to help-seeking (n = 8). This was a significant barrier for studies including rural and immigrant populations, and in studies that included parents in their sample. Six studies focused on the relationship between symptomatology and help-seeking. These found that higher levels of psychological distress, suicidal ideation and depressive symptoms were linked to lower help-seeking behaviours.

Help-Seeking Facilitators

Of the 56 included studies, 19 also referred to facilitators of help-seeking behaviours. Mental health literacy and prior mental health care were the most cited facilitators for help-seeking for mental health problems (

n = 10). Specifically, timely access to mental health was facilitated by having a previous positive experience with mental health services or help-seeking, being familiar with the sources of help, and good symptom and problem recognition. Higher engagement with the community and having a trusting and committed relationship with relevant adults such as parents, schoolteachers and counsellors also facilitated seeking help among adolescents. Further details of the included articles are available in

Table 2.

Secondary Outcomes

Few studies identified a significant difference when comparing younger and older adolescents in relation to barriers and facilitators to help-seeking, with no conclusive findings being reached. Some findings suggested that older adolescents tended to establish to feel more comfortable with people with mental health issues [

83] and had less help-seeking fears [

40]. In contrast, younger adolescents had greater knowledge about professional sources of help [

34]. Only one study found a significant difference between ages regarding help-seeking, with younger adolescents reporting higher intentions of seeking help [

60].

Twenty-four studies examined possible gender differences in help-seeking barriers and facilitators. Seven studies did not find significant differences between genders [

28,

39,

40,

42,

46,

51,

69]. One study reported higher help-seeking intentions in males experiencing suicidal intentions [

60] and two studies found that females perceived more overall barriers [

26–

58]. However, this may be related to higher rates of females seeking help for mental health problems compared to males [

31,

33,

37,

42,

48,

53,

58,

61,

76]. Studies reviewed did not evidence convincing differences between gender in relation to help-seeking.

Question 2: Help-Seeking Interventions

Thirty-six studies on interventions targeting help-seeking behaviour, including a total of 28,608 participants, were summarised in the review (

Table 3). Most of intervention studies were conducted in Australia (14) and the United States (14), followed by Canada (4) and United Kingdom (3). All studies were conducted in educational setting including high school (

n = 35) and college (

n = 1). The majority of studies developed interventions for non-clinical samples, and their focus was the prevention of mental health problems and the promotion of healthy coping strategies via help-seeking behaviours. Outcomes varied between help-seeking intentions, attitudes and behaviours. Almost half of the studies focused on the effectiveness of the interventions, while sixteen were feasibility or pilot trials and study protocols. Most of the studies used a quasi-experimental design (

n = 21) followed by randomised controlled trials (

n = 15). The age of participants ranged from 11 to 19 years old, although one study that included participants under 29 years old was incorporated as more than half of the sample were adolescents. Interventions were delivered using four main methods: psychoeducation, outreach interventions, multimedia tools and peer leader training.

Types of intervention

Psychoeducation.

Most of studies (n = 23) used psychoeducation and classroom-based interventions. Although all the interventions focused on encouraging help-seeking behaviours, the emphasis and content differed among them, including general mental health topics, suicide and depression awareness and stigma.

Five studies developed programmes based on the notion that promoting mental health awareness could enhance mental health literacy and promote help-seeking [

84–

88]. Four interventions targeting help-seeking for suicide were identified within five studies [

89–

93]. Five interventions explicitly targeted help-seeking for depression in school-based settings their focus being to educate the school population about adolescent depression and thereby encourage help-seeking [

94–

98]. Two studies evaluated the effectiveness of an intervention combining depression awareness and a suicide prevention programme promoting early identification and self-referral [

99,

100]. Six classroom-based interventions addressing stigma were identified, two of which used psychoeducation to overcome myths regarding mental illness [

101,

102] and four focused on providing interpersonal contact with people with mental health conditions in order to improve acceptance and increase help-seeking intentions [

103–

106].

Outreach interventions.

Three studies used outreach interventions to target mental health help-seeking [

107–

109]. These aim to establish contact with adolescents who may be experiencing psychological and emotional distress in order to help them get the attention they need and increase their access to health services. They were based on the Building the Bridges to General Practice (BBGP) programme, developed by Wilson et al. (2005), a programme that aims to target help-seeking obstacles for physical and psychological problems by promoting contact between high school students and general practitioners [

110].

Multimedia interventions.

Six types of multimedia interventions have been developed to address some of the difficulties of reaching an adolescent population, such as fear of confidentiality breaches, stigma and self-reliance [

111–

115]. The interventions included interactive films to engage students with mental health related topic and online platforms providing personalised information regarding the decision-aids process.

Peer training interventions.

Peer training interventions are focused on the training of peers who act as active agents of change and social interactions incorporated into the daily activities within the school environment [

116]. All three programmes followed similar principles concerning improving the climate around mental health problems, promoting social connectedness, and challenging norms and behaviours associated with help-seeking [

117–

120]. “Peer leaders” acted as a link between the student population and mental health literacy, promoting the acceptability of seeking for help for mental health problems.

Further details of the included articles are available in

Table 3.

Secondary outcomes

No studies referred to significant differences concerning the effectiveness of help-seeking interventions when comparing ages. No significant gender differences were identified regarding the effectiveness of the help-seeking interventions [

89,

101,

103,

111]. However, before the intervention¸ females tended to have higher mental health literacy and more adaptive attitudes regarding mental health problems [

90,

111], including greater help-seeking knowledge and intentions [

107,

112,

113].

Effectiveness

The main goal of this review was to describe the interventions targeting help-seeking in adolescents and therefore did not include an analysis of their effectiveness. Almost half of the included studies were study protocols and feasibility studies, so effect sizes were not reported. However, some findings are worth mentioning.

Four studies which looked at effectiveness of the interventions focused on psychoeducation about depression found a significant effect in increasing help-seeking. King et al., [

99] identified that there was an increase in future help-seeking behaviours after the interventions and that this was maintained at 3 months’ follow-up (

t = 4.634/

p < .001). Strunk et al., [

100] found a significant increase of help-seeking (

p < 0.0005); however, this was not sustained at follow-up (

p = 0.014). Robinson et al., [

95] found that the intervention group was more likely to seek help at post-test (Odds ratio (95% C.I) =3.48 (1.93, 6.29),

p < 0.0001) and Ruble et al., [

96] found increased intention of help-seeking from others after the intervention (

t = 13.658/

p < 0.0001).

The three studies that looked at the effectiveness of stigma reduction identified positive effects of the intervention on help-seeking. Two studies [

101,

104] found a significant reduction in self-stigma surrounding seeking help after the intervention (

p < 0.05) and one study [

103] found a significant effect of the intervention in help-seeking intentions (Wilks’ Λ = .942,

F (4,417) = 6.428,

p < 0.001).

Finally, all the studies that focused on outreach found a significant effect of the intervention in help-seeking intentions. One detected an increase in intentions at 3 months follow-up (

F (2,217) = 3.04/ p < 0.05) [

108], Rughani [

107] found short terms improvements in help-seeking intentions (

F (14,225) = 1.87

p < .03) and Wilson [

109] found a significant effect in the intention of seeking help for psychological problems after the intervention (

F (2,598) = 4.31

p < 0.01).

Quality Assessment

The majority of the studies were low to medium quality with moderate to high risk of bias. Most of the cross-sectional studies did not state a clear inclusion and exclusion criteria and did not consider possible confounders affecting the interpretation of the outcome. Regarding qualitative research, the most common problem was linked to sample size and the difficulty of providing a clear strategy to address the subjectivity of the authors in the interpretations of the data. Mixed method studies presented some inconsistencies in addressing specific components of both quantitative and qualitative traditions, and in the process of integrating both approaches. Regarding intervention studies, it was difficult to identify to what extent the groups were similar at baseline. Although some studies included baseline measures of demographic information, most of them did not consider confounders or other factors influencing effectiveness, and some studies did not have any baseline measures. Also, few studies included follow-up and the ones that did, had high attrition rates and short follow-up periods (up to 6 months); therefore, it is not possible to attribute a long-lasting effect to the interventions. Quasi-experimental studies acknowledge possible selection and sample bias. Randomised controlled trials presented difficulties in terms of the blinding of the research team and participants at different stages of the process.

Overall there was inconsistency regarding the measurements of help-seeking, with most of the studies focusing on help-seeking intentions, which is not necessarily related to future behaviours. Moreover, many studies did not use valid and reliable instruments for measuring help-seeking. This is especially true for the experimental studies since most of them developed tools focused on their intervention rather than standardised help-seeking measures. Finally, most of the studies only used self-report measures, increasing the risk of bias of the findings. We did not assess the quality of study protocol, feasibility studies and pilot studies.