To the Editor: Steroid-responsive encephalopathy associated with autoimmune thyroiditis, also reported as Hashimoto encephalopathy (HE), is a rare autoimmune encephalopathy associated with the presence of serum antithyroid antibodies, normally presenting as an acute or subacute onset of various neurologic and neuropsychiatric syndromes.

1,2 However, in the past, only a few cases were reported with purely psychiatric symptoms.

3–6 We present another case of HE with strictly psychiatric symptoms, additionally, showing no initial clinical steroid responsiveness, but with complete recovery after treatment with cyclophosphamide.

Case Report

A 49-year-old woman was admitted to our hospital, presenting with fluctuations of consciousness, severe cognitive impairment, memory loss, hallucinations, delusions, functional decline, catatoniform movement abnormalities, psychomotor slowness, mutism, and depressive mood over weeks. Medical history included Hashimoto thyroiditis with euthyroid status under levothyroxine 125 µg/day.

Full neurologic and physical examination and routine biochemical and serological laboratory tests, including thyroid function tests, ammonia, vitamin status, rheumatoid factor, several autoantibodies, tumor marker, drug screening, and serologies were normal. Thyroid microsomal and thyreoglobuline antibodies were also negative; however, high titers of serum anti-thyroperoxidase autoantibodies (anti-TPO), with 4,717.3 kU/L (−60) became apparent. Initial EEG showed intermitted generalized slowing and epileptiform abnormalities. Cranial MRI and FDG-PET scan remained unremarkable. Routine CSF tests showed protein elevation, with 715 mg/l (140–500) and positive oligoclonal bands. Tau protein, amyloid β 1–42, protein 14–3-3, and antineuronal antibody screening in CSF were negative.

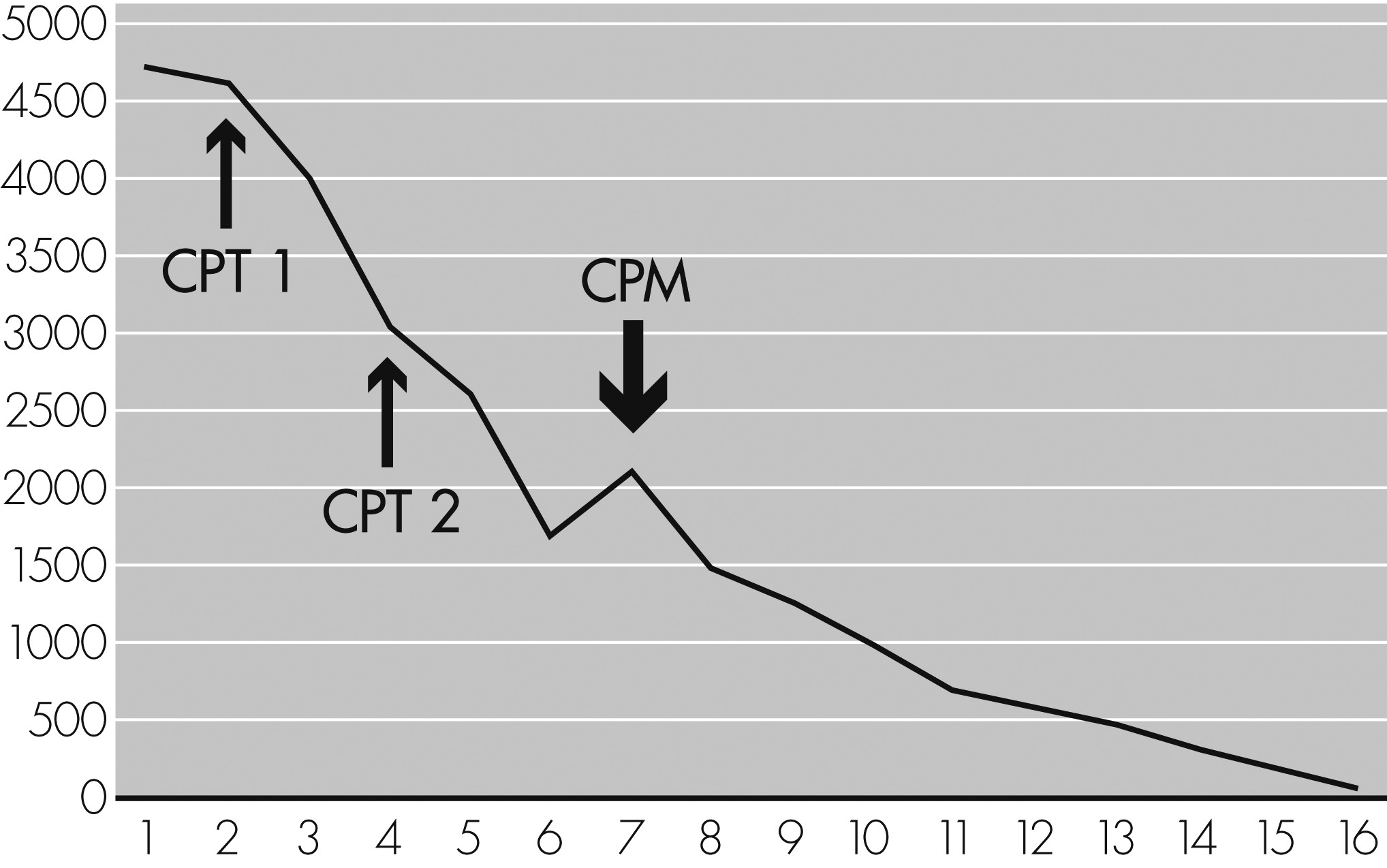

Our results confirmed the diagnosis of HE, so an i.v. pulse therapy with methyl-prednisolone 1g/d was initiated, followed by oral prednisolone maintenance, which produced no clinical improvement. However, because of the declining trend in the serum anti-TPO levels (

Figure 1), we initiated a second steroid pulse therapy, which also failed to produce any clinical improvement, but which led to a further decrease of anti-TPO levels and a normalization of EEG and CSF abnormalities. Subsequently, the anti-TPO serum level showed a new increase; therefore, we initiated an add-on cyclophosphamide treatment (750 mg/m

3). Cyclophosphamide finally led to a rapid and significant clinical improvement accompanied by a further decrease and, finally, a normalization of anti-TPO serum levels. The patient reached complete and stable remission within weeks, and a follow-up 6 months later showed no relapse.

Discussion

HE often mimics other psychiatric disorders, especially psychotic and dementia syndromes, regularly leading to delayed diagnosis and proper treatment.

1,3,4 Also, our case shows that even after proper treatment, clinical improvement may be absent or significantly delayed especially at higher thyroid antibody titer levels.

We therefore suggest the implementation of thyroid-antibodies tests in the routine screening of psychotic patients, independently of thyroid status. Furthermore, in case of steroid partial or non-response, we suggest that immunosuppressant treatment be considered much earlier, in order to avoid chronicity or progression of symptoms. Our case also supports the monitoring of anti-TPO levels as an additional reliable outcome parameter of response and remission.

7 Finally, we do not recommend the further use of the term “steroid-responsive” as part of the descriptive name of the disease. "Encephalopathy of autoimmune thyroiditis (EAT)" would probably be more suitable and regularly applicable.