To the Editor: Disulfiram, an inhibitor of acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, has been used in the management of alcohol dependence as a deterrent agent. The major adverse events with disulfiram include hepatic, neurologic, psychiatric, and dermatologic reactions. There are few reports of seizures associated with disulfiram.

Disulfiram has been used in the management of alcohol dependence as a deterrent agent for over 50 years, and it has been shown to be efficacious when taken under supervision.

1 It inhibits acetaldehyde dehydrogenase, leading to accumulation of acetaldehyde after consumption of alcohol, which in turn results in distressing symptoms such as flushing, palpitations, fall in blood pressure and syncope, nausea, and vomiting.

2 The major adverse events with disulfiram include hepatic, neurologic, psychiatric and dermatologic reactions; among them the neurologic adverse effects constitute up to 28%, making the nervous system the most affected organ system.

3 The neuropsychiatric adverse effects reported are optic neuritis, headache, ataxia, paresthesias, delirium, convulsions, dysarthria, frontal release signs, anxiety, impaired memory, decreased concentration, depression, and psychosis.

4 We report on a case where the patient developed myoclonic seizures while on disulfiram.

Case Report

“Mr. P,” a 30-year-old single man diagnosed with alcohol dependence for the past 12 years presented with uncomplicated withdrawal symptoms. Detoxification was done using benzodiazepines in tapering dose, and vitamin supplementation was initiated. Nonpharmacological interventions, including cognitive-behavioral strategies, were done for relapse-prevention. Investigations, including complete blood count, blood sugar, liver, and renal function tests were within normal limits. After he gave written informed consent, disulfiram was started at a dose of 250 mg at bedtime as an aversive agent. He was also receiving amitriptyline 50 mg at bedtime for chronic daily headache. His birth and developmental history was unremarkable. There was no past or family history of major medical or psychiatric illness. Premorbidly, he had impulsive traits.

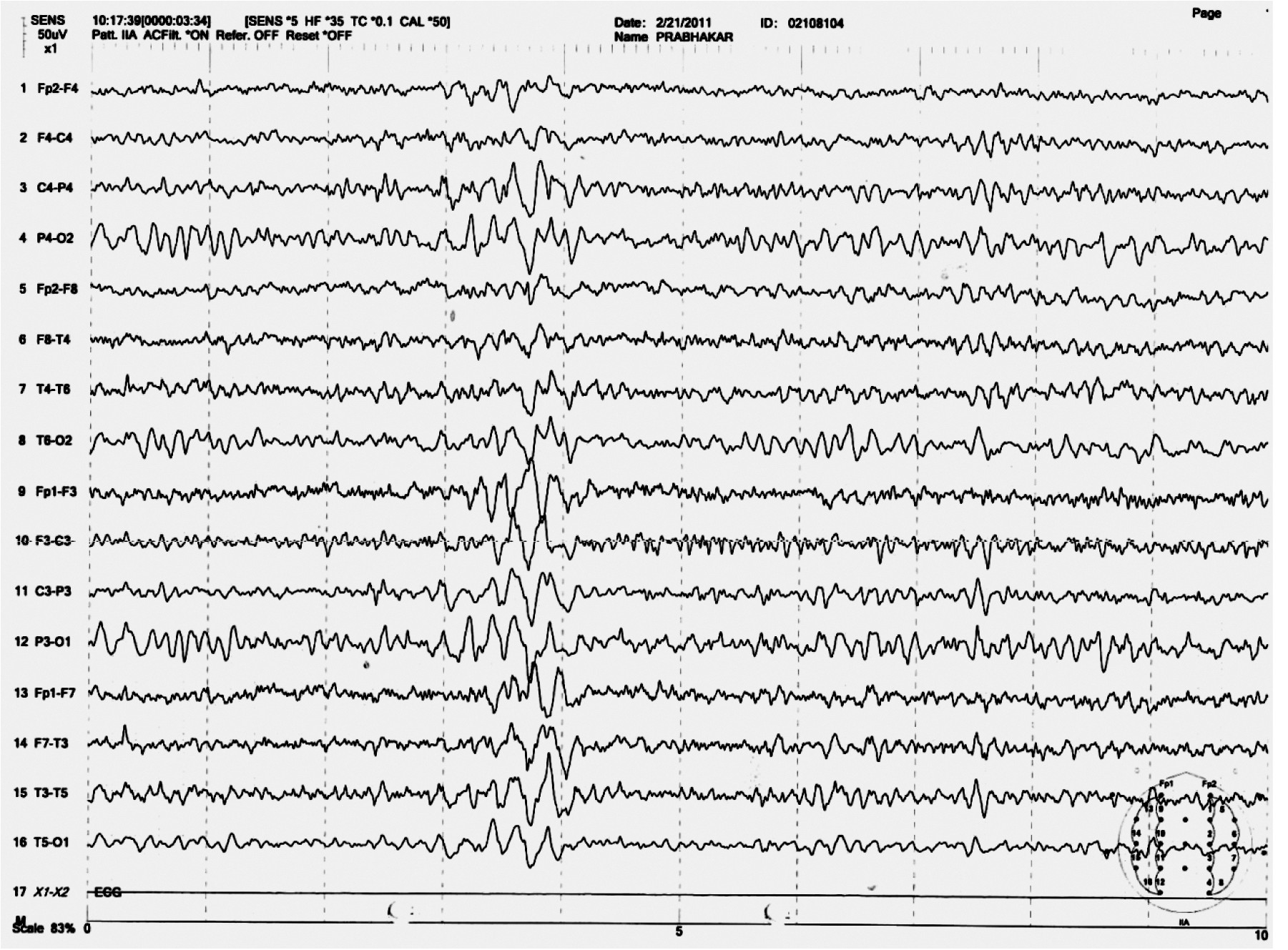

He had been on regular medications under the supervision of a family member and abstinent from alcohol after discharge from the hospital. After 1 month, he presented with a 4-day history of sudden jerky movements of the body with increasing frequency. The number of such movements increased over the 4 days, and, on the 4th day, he had fallen down and was unconscious for a few seconds. There were no tonic or clonic movements of the body. He was admitted for observation. Electroencephalography (EEG) done on the 5th day showed generalized spike and wave discharges (

Figure 1). He was diagnosed with myoclonic seizures possibly related to disulfiram, and all his medications were discontinued. The Naranjo Adverse Drug Reaction (ADR) probability scale

5 score was 6, which suggests a probable association. From the next day onward, the frequency of the myoclonic jerks gradually decreased, and, on the 8th day, he did not have any such episodes. He was discharged on the 9th day and started on acamprosate as anticarving agent and amitriptyline. At follow-up, after 2½ months, there was no recurrence of such episodes. He had stopped medications after 1 month and had restarted consuming alcohol for 2 weeks. A repeat EEG done at this time was normal.

Discussion

In this patient, disulfiram was considered the cause of his myoclonic seizures since he did not have any history of seizures in his family or in the past. The episodes started 1 month after starting disulfiram and stopped after the drug was withdrawn. Amitriptyline can also cause seizures, but it is usually related to higher doses and in predisposed individuals.

6 Furthermore, there was no recurrence of seizures after reintroducing amitriptyline; this implicates disulfiram as the causal agent. This pattern of appearance of adverse effects with increase in duration of drug exposure has been described in the nervous system.

3 There are rare case reports of seizures associated with disulfiram. In three reports, the patients had generalized convulsions,

7–9 and another case had drop attacks.

10 To our knowledge, there are no reports of myoclonic seizures associated with disulfiram.

The mechanism of seizures associated with disulfiram is not known. The most important toxic metabolites are disulfiramarediethyldithiocarbamate (DDC), and its metabolite, carbon disulfide (CS2).

11 DDC chelates copper, thus impairing the activity of dopamine betahydroxylase.

2 Studies have found that disulfiram and DDC increase the release of glutamate from striato-cortical synaptic vesicles, both in vitro and in rats, suggesting a possible mechanism for DDC-mediated neuronal damage and development of seizures.

12,13 Another possible mechanism could be exposure to CS2,

14,15 acute exposure to which causes rapid onset of headache, confusion, nausea, hallucinations, delirium, seizures, coma, and, potentially, death.

8,9 Noradrenergic transmission has been implicated in the modulation of seizure activity. Norepinephrine depletion with disulfiram exacerbates seizures and facilitates seizure kindling.

10Although the frequency of seizures associated with disulfiram appears to be low, caution needs to be taken when prescribing this medication in those with risk factors for seizure. Also, myoclonic seizures could be another possible manifestation of disulfiram toxicity, in addition to generalized convulsions and drop attacks. Nevertheless, larger studies are required to document the association of seizures with disulfiram therapy.