Impulse-control disorders (ICDs), characterized by a failure to resist an impulse, drive, or temptation to perform an act that is harmful to the person or others,

1 have been increasingly recognized as a problem in Parkinson’s disease (PD). Cross-sectional prevalence for any ICD has been reported to be 14%, with roughly similar rates for each of four main types, including pathological gambling (PG), compulsive buying, compulsive sexual behaviors, and binge-eating behaviors, and more than one-fourth suffering from two or more ICDs.

2 The behaviors involved in ICDs are thought to be due to dysfunctional dopaminergic stimulation in reward systems of the brain and have been likened to behavioral addictions.

3 These disorders can have severe, negative consequences for PD patients and their families, as evidenced by published reports of ICD-related suicidality, marital discord, and financial ruin.

4,5 Studies and clinical practice have implicated dopamine-agonist (DA) use as a main risk factor for development of ICDs in PD,

2,6,7 although this is not exclusive, and a contribution of levodopa is not excluded.

2 Other risk factors for ICDs include younger age, younger age at PD onset, being unmarried, a family history of gambling or alcohol problems, and a novelty-seeking personality,

2,8 with some characteristics associated with particular ICD types, such as male gender in the case of PG and hypersexuality.

9 Higher levels of depressive, anxiety, and obsessive-compulsive symptoms have also been reported in PD patients with ICDs.

10,11Studies of the neuro-cognitive characteristics associated with ICDs in PD have yielded mixed results. Executive dysfunction was shown in one study to be predictive of PG in a sample of PD patients without dementia,

12 with deficits in set shifting and spatial planning,

13 and working memory

14 reported in PD patients with various ICDs compared with those without, consistent with studies of ICD in non-PD populations.

15 In contrast, others have found a lack of difference in executive functioning

8 and equal or even higher performance

16–18 in PD samples with ICD versus those without. Memory deficits have been reported in samples with hypersexuality and compulsive eating,

13 but are generally thought to play less of a role than executive functions in ICD behaviors.

Impaired self-awareness or insight has been recognized as a feature of a number of neuropsychiatric disorders,

19 including PD. PD patients have been shown to have impaired awareness in a range of pathologic behaviors, including cognitive deficits,

20,21 psychiatric symptoms (including punding, a non goal-directed ICD)

22–28 and social dysfunction.

20,26 However, self-awareness has not been examined in PD patients across the range of ICD types. The aim of this exploratory study was to investigate the correlations between clinical, neuropsychological, and self-awareness measures in PD patients with and without ICD. It was hypothesized that PD patients with current ICD (PD-ICD) would display greater deficits in self-awareness than PD patients without current ICD (No-ICD).

Results

The demographic and PD-related characteristics of participants completing assessment (N=34), broken down into PD-ICD and No-ICD groups, are shown in

Table 1. Compared with No-ICD, PD-ICD were younger at the time of PD diagnosis and suffered more motor complications of PD therapy (UPDRS, part IV), whereas motor symptom severity (UPDRS, part III), dopamine agonist use, and LEDD were comparable between the two groups (although the total LEDD was nonsignificantly greater in the PD-ICD group;

Table 1). In the PD-ICD group (N=17), 3 each met single criteria for pathological gambling and compulsive shopping, 2 each for compulsive eating and compulsive sexual activity, and 7 met criteria for two or more ICDs. All participants except one, who was a resident in a minimal-assistance retirement community, were living in their own homes at the time of the assessment. Caregivers (N=34) consisted of a 26 spouses, 5 adult children, 2 friends, and 1 sibling, with no significant differences in caregiver-type between the two groups.

Neuropsychiatric Symptoms

PD-ICD and No-ICD did not differ significantly in terms of reported depressive symptoms (

Table 2). On average, both groups reported depression symptoms in the mild range. Significantly more participants in PD-ICD than No-ICD were currently being treated with an antidepressant or antianxiety medication (58.8% versus 17.6%; χ

2[1]=6.103; p=0.01). Individual NPI items showed no between group differences.

Neuropsychological Testing and Awareness Measures

There were no significant differences between PD-ICD and No-ICD in premorbid IQ, screening MMSE score (range: 26–30), or performance on any of the neuropsychological tests of memory or executive function (

Table 2).

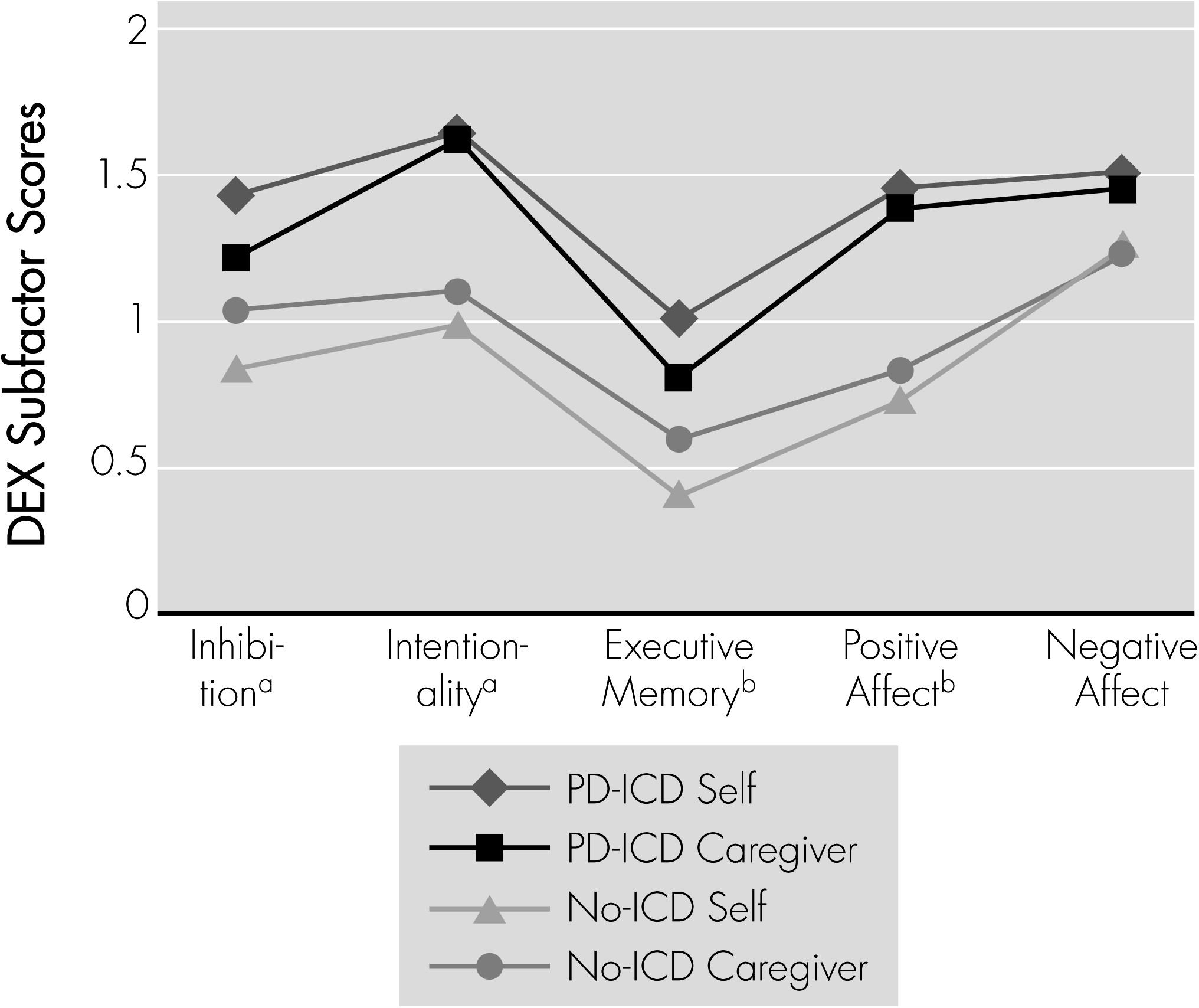

Mean participant and caregiver ratings of everyday executive and memory function problems (DEX and EMQ, respectively) and corresponding participant–caregiver discrepancy scores are shown in

Table 2. Self-rated executive functioning (DEX total score) was significantly lower in PD-ICD than in No-ICD, but total caregiver DEX score did not differ between the groups. Although the total DEX discrepancy score suggests greater awareness in the PD-ICD group, the difference was not significant (

Table 2). Similar results were found in the DEX subscales (

Figure 1) with none of the discrepancy scores reaching significance (Inhibition:

t[32]=1.33; NS; Intentionality:

t[32]=0.525; NS; Executive Memory:

t[32]=1.95; p=0.06; Positive Affect:

t[32]=1.08; NS; Negative Affect:

t[32]=0.12; NS). Relevant to the issue of ICDs, the PD-ICD participants rated themselves significantly higher than No-ICD on the main DEX Impulsivity question (“Acts without thinking”) (

t[32]=2.75; p=0.010). BCIS scores revealed greater overall Cognitive Insight and a trend toward greater Self-Reflectiveness in PD-ICD than in No-ICD, but no significant difference in the Self-Certainty subscore between groups (

Table 2). EMQ self-ratings were significantly higher in PD-ICD than No-ICD, indicating more subjective memory complaints, with discrepancy scores reflecting a greater awareness of memory problems in the PD-ICD group (

Table 2).

For the sample as a whole (N=34), BDI scores were not significantly correlated with DEX Discrepancy score (r[32]=0.28; NS) or BCIS score (r[32]=0.16; NS), but were significantly correlated with EMQ Discrepancy score (r[32]=0.47; p=0.005); that is, greater depression, more memory problems.

Discussion

To our knowledge, this is the first formal study to explore self-awareness of cognitive and behavioral issues in a sample of PD patients affected by the range of ICDs. The presence of ICDs was associated with awareness of impulsive behaviors and memory problems, as indexed by DEX and EMQ discrepancy scores, respectively, and greater cognitive insight into thoughts and behaviors on the BCIS, as compared with the No-ICD group. There was no difference in frontal executive dysfunction on neuropsychological testing between PD-ICD and No-ICD, a finding in line with some previous studies.

13,14,18 Despite the lack of neuropsychological deficits as compared with No-ICD, PD-ICD participants self-reported significantly more everyday problems related to executive dysfunction, including impulsivity. These findings support the idea that PD patients with ICDs are less able to resist engaging in impulsive behaviors related to gambling, sex, eating, and shopping, despite recognizing their impulsivity.

In contrast to the present findings, impaired awareness of motor,

41–43 cognitive,

20,21 psychiatric,

22–28 and social problems

20,26 have been demonstrated in PD in previous studies. A model of such domain-specific impairments of awareness in neuropsychiatric disorders has been proposed, with the possibility of isolated impairments in particular domains.

19 One proposed mechanism for such impairments in awareness relates to impaired ability to “shift set,” leading to a faulty appraisal of performance, poor recognition of failure, and a resultant lack of update of the patient’s “personal database.”

44 This explanation appears applicable to ICDs in PD, given the characteristic inability to refrain from potentially harmful behaviors, despite repeated failures and negative consequences. However, the present study found an intact ability to “set-shift” in PD-ICD, as assessed by the TMT (Trail-Making Test) B–A score, although impairments on the same task have been previously reported to be associated with PD-ICD.

13 Cilia et al.

45 postulate that PD subjects with pathological gambling (PG) have impaired set-shifting after negative outcomes, and correlate this impairment with an anterior cingulate cortex–striatal disconnection in those with PG versus controls. Regarding our results, it may be that the TMT does not provide adequate risk–reward valence to examine set-shifting as it relates to ICD behaviors or is insufficiently demanding, since there are only two fixed ‘sets’ and shifts are predictable (cf.: the Wisconsin Card Sort test [WCST]). A recent study of altruistic punishment (punishing others to enforce social norms at a cost to oneself) in PD patients with ICD found that patients with ICD in the “on” medication state were more likely than controls to punish unfair investing behaviors carried out by others. Although not examining “set-shifting,” per se, this study highlights the idea that PD patients with ICDs may recognize problematic behaviors in others while lacking awareness of the problems caused by their own behaviors.

46 This is relevant to ICDs in that being aware of impulse-control behaviors is not the same as recognizing them as problematic. This involves a different level of awareness in the domain of social cognition, an area that we did not specifically assess. Where the problem relates to its impact on others, social cognition may be critical and more important than executive functioning.

ICDs have consistently been associated with DA treatment,

2,6,7 although it is clear that medications alone are not sufficient to cause ICD. In our sample, there was no significant difference between PD-ICD and No-ICD in the percentage of patients taking DAs, possibly because of increased vigilance among prescribers. Total LEDD was nonsignificantly higher in PD-ICD than in No-ICD. Overall, LEDDs were high as compared with those for PD samples on average, possibly resulting from a cohort of less-responsive cases being seen in the specialty movement disorders clinic from which we recruited participants. Voon et al.

47 propose that differences in response to nonphysiologic dopaminergic stimulation are due to individual susceptibilities and differences in striatal function, and liken ICDs to a behavioral form of medication-related dyskinesias. Indeed, PD-ICD in our study also had more complications of PD therapy than No-ICD participants, despite similar LEDD across the two groups. Another recent study found a similar association between ICDs and motor fluctuations.

48 Interestingly, Amanzio et al.

42 examined awareness of dyskinesias in a PD sample and found high levels of unawareness while in the “on” state, with unawareness associated with set-shifting deficits on the WCST. They attributed this finding to levodopa’s detrimental effect on frontal-cingulate-subcortical circuits, which are felt to be important in awareness phenomena. Given similarities across disinhibitory pathologies, some authors have proposed that ICDs should be examined as part of a continuum of disinhibited movements, acts, and emotions affected by the basal ganglia, including levodopa-induced dyskinesias

47 and other addictions,

49 with the goal of elucidating mechanisms that will guide research and treatment.

Increased depressive and anxiety symptoms have been associated with ICDs in PD,

10,11 although we found depression symptoms to be comparable in PD-ICD and No-ICD. It is generally thought that depressive symptoms increase as patients become more aware of their deficits or problems (and vice versa), and this has been shown in various neuropsychiatric populations.

19 In our study, depression scores correlated with awareness of memory deficits, but not with awareness of executive functioning or cognitive insight. PD-ICD participants did not report more depressive symptoms than No-ICDs, despite intact awareness of their problems and higher self-ratings on DEX and EMQ. However, significantly more participants in the PD-ICD group were being treated with an antidepressant at the time of this study, indicating that PD-ICD patients may experience more depressive symptoms overall albeit remitted due to treatment. Furthermore, patients in remission may still maintain a depression-related cognitive style, including negative self-perceptions, which may explain overestimation of cognitive problems.

There are a number of limitations to consider in this study. First, our sample size was small and may not have provided adequate power to detect smaller differences across variables. However, the aim of this study was exploratory in nature and should serve as a basis for examining the relationship of neuropsychological factors and awareness in ICDs on a larger scale. Secondly, the validity of using patient–caregiver discrepancy methods to assess awareness depends on the caregiver as the “gold standard” for reporting patients’ problems or deficits. This may be problematic, as caregiver reports might be skewed by factors such as perceived caregiver burden, depression, or a lack of familiarity with the subtleties of patient deficits (i.e., having greater knowledge of the patients’ forgetting something than the patients themselves). However, this method has been used extensively in neuropsychiatric populations and consistently shows underestimation of deficits on behalf of patients in relation to caregivers. Studies specifically examining this issue in PD have shown good agreement of caregiver reports with clinician assessments on objective measures.

20,21,50,51 Also, we used a questionnaire, the DEX, to query participants about dysexecutive problems in everyday life, including impulsivity, as a surrogate for impulsive behaviors in ICDs. The DEX picked up increased problems in the ICD group according to patient (and caregiver) ratings. However, this is not a substitute for scales assessing insight into ICD behaviors specifically and may limit the validity of the awareness findings. Incorporating ICD-specific instruments into future work will be important for drawing conclusions about the role of self-awareness in ICD behaviors. Last, we recruited participants from a tertiary movement disorders clinic population and some from a trial examining a psychosocial intervention for ICDs. Hence, this group is likely to have had PD-related problems, such as ICDs, brought to attention previously. Therefore, this group (both ICD and No-ICD) may be more aware of their PD-related problems than PD patients in the general population. This factor may also account, at least in part, for the young age at PD diagnosis in our sample. It should also be noted that we excluded patients with MMSE scores <24, and no participant scored <26; hence unselected populations of PD patients with ICDs may include those with generalized and specific executive deficits, which are likely to complicate their disorders.