While post-stroke depression has received considerable attention in the literature,

1 apathy after stroke, in particular, its negative impact on rehabilitation and recovery in stroke patients,

2–4 has been less well examined, despite its clinical significance. Rates of apathy after stroke range from 19% to 50%,

3,5–14 depending on the sample, time of measurement, and method of assessment. Most studies have been cross-sectional. The single longitudinal study of apathy reported that scores peaked 3 months after a stroke, but then abated over 12 months, even when allowing statistically for higher attrition among apathetic patients.

5 This contrasts with evidence of increasing rates of apathy in normal elderly people,

15 and in those with dementia and with the known high likelihood of dementia after stroke.

16 In the Mayo et al. study,

5 poor cognitive status, low functional status, and high comorbidity predicted higher apathy. In turn, high apathy had negative effects on physical functioning, participation, health perception, and physical health over the first 12 months after stroke.

We previously reported data from the Sydney Stroke Study

3 indicating that apathy was more frequent in stroke patients than in controls. Apathetic stroke patients were older, more functionally dependent, and had lower Mini-Mental State Exam (MMSE)

17 scores than those without apathy. We report here the longitudinal course of apathy after stroke over 5 years. Our hypotheses were that apathy would become more pronounced, given the natural history of progression of cerebrovascular disease,

18 and that increasing apathy would be associated with worsening cognition, poorer functional status, and dementia onset.

Results

The Sample

At baseline, control and stroke patient groups were similar in age and sex ratio, but controls had completed more years of education (

Supplementary Table S1). Of 202 stroke patients recruited at baseline, there were no significant differences between the age and sex of the 152 included and 50 excluded patients. Those included had completed more years of education (

Supplementary Table S2).

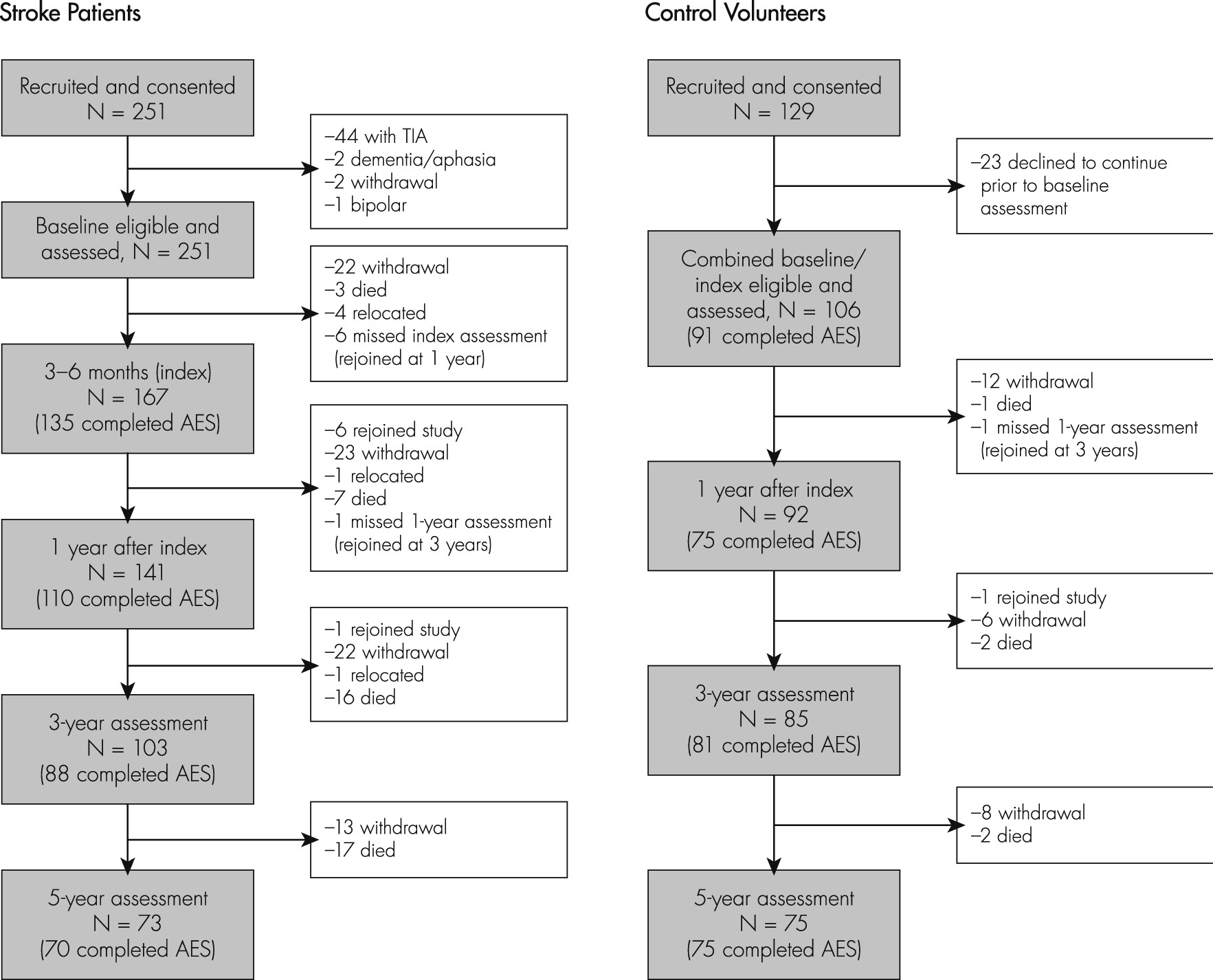

Sample Attrition and Predictors of Missing Data

When missing-ness was tested as a binary outcome variable using logistic regression, more disabled patients were more likely to have missing data AES at 5 years. Of 152 patients in this sample, 70 had AES data at the 5-year assessment. Univariate logistic regression was used to analyze predictors of missing AES data at 5 years. Apathy at index was not a significant predictor (odds ratio [OR]: 1.54; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 0.70–3.37), but Apathy at 1 and 3 years predicted missing AES data at 5 years (OR: 4.53, 95% CI: 1.94–10.57; OR: 5.59, 95% CI: 2.11–14.83, respectively). Dementia at Index, 1, and 3 years (OR: 6.27, 95% CI: 2.04–19.28; OR: 17.68, 95% CI: 3.90 to −80.23; and OR: 4.57, 95% CI: 1.71–12.22, respectively) and lower ADL/IADL scores at Index, 1, and 3 years (OR: 0.72, 95% CI: 0.61 to −0.86; OR: 0.74, 95% CI: 0.64–0.85; and OR: 0.83, 95% CI: 0.75–0.93, respectively) also predicted missing AES data at 5 years. Other significant predictors of missing AES data at 5 years were higher GDS scores at Index, 1-year, and 3-year assessments (OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.03–1.36; OR: 1.18, 95% CI: 1.03–1.36; and OR: 1.25, 95% CI: 1.06–1.47, respectively).

Of the 101 control participants, 75 had AES data at the 5-year assessment. Univariate logistic regression was used to analyze predictors of missing AES data at 5 years. Contrary to the systematic attrition in patients, missing 5 year AES data in controls were not predicted by physical or cognitive disability. This indicates that AES levels over time and AES slopes are not comparable between the two groups.

Demographic and Clinical Characteristics

At Index assessment, patients’ mean age was 72.1 (SD: 8.88) years; they had completed 10.2 (SD: 2.75) years of education; 57.9% (88/152) were men. Apathetic patients were older, had lower ADL/IADL scores, and were more likely to have dementia than those without apathy (

Supplementary Table S3).

At Index, controls were age 71.1 (SD: 6.1) years and had completed 11.8 years of education; 48.5% (49/101) were men. Four controls (4.4%) were classified as apathetic (4/91). Apathetic control subjects were similar to those without apathy at Index regarding age, education, ADL/IADL scores, and gender ratio (t[89]=1.39, NS; t[89]=0.19, NS; t[88] = −0.49, NS; OR: 2.67, 95% CI: 0.26–26.72, respectively).

Apathy Scores and Rates in Patients and Controls in the Not-Imputed Data

In the observed sample data, mean Apathy scores in the Patient sample increased from 32.2 (SD: 10.27) at Index assessment to 33.4 (SD: 10.23) at 1 year, 36.8 (SD: 14.04) at 3 years, and 37.1 (SD: 10.82) at 5 years. This occurred despite greater attrition of patients with more apathy. Similarly, rates of apathy steadily rose from 26.7% (36/135) at Index assessment, 33.6% (37/110) at 1 year, 34.1% (30/88) at 3 years, to 38.6% (27/70) at 5 years.

In the 45 Completers (patients who completed all AES ratings), mean AES scores were similar at Index (29.8; SD: 10.2) and 1 year (29.0; SD: 8.4), but increased to 32.6 (SD: 11.7) at 3 years, and 36.7 (SD: 11.5) at 5 years. However, these scores likely represent the least disabled group among the patients and are therefore not representative of the total sample.

Among the 101 control subjects, observed AES scores increased from a sample mean of 24.0 (SD: 6.08) at Index to 26.3 (SD: 6.90) at 1 year, 26.8 (SD: 7.92) at 3 years, and 29.2 (SD: 7.73) at 5 years. Rates of Apathy in control subjects rose from 4.4% (4/91) at index to 8.0% (6/75) at 1 year, 9.9% (8/81) at 3 years, and 16.0% (12/75) at 5 years.

When using linear mixed models in the observed (not imputed) data to compare AES levels in patients and controls, there were significant differences in AES scores (estimate: 7.47 [standard error {SE}: 1.10], p <0.0001), as well as change in AES over time (estimate: 0.01 [SE: 0.01], p=0.007), between the two groups. Patients had higher AES scores, on average, across the visits, and greater increase over time, as compared with the control group.

Progression and Predictors of Apathy in the Imputed Data

Linear mixed models based on the imputed data were used to describe the progression and predictors of apathy over time. AES scores in patients increased significantly over 5 years (parameter estimates with multiple imputation — intercept: 41.10 [SE:3.44], 95% CI: 34.12–48.08; df:36, p <0.0001; slope: 0.02 [SE: 0.004], 95% CI: 0.01–0.03, df: 62, t=4.35, p <0.0001). These results were consistent with parameters estimated without multiple imputation (intercept: 31.79 [SE: 0.83], t[151]=38.22, p <0.0001; slope: 0.03 [SE: 0.004], t[124]=7.80, p <0.0001).

Predictors at Index Assessment (3–6 months after baseline recruitment)

Using univariate linear mixed models for index variables, lower ADL/IADL score, dementia, higher GDS, and interval cerebrovascular events (between Baseline and Index) were associated with higher AES scores over time (

Table 2).

Time-Varying Predictors

The variables dementia, ADL/IADL, and GDS were additionally measured as time-varying variables across four time-points. Using univariate linear mixed models for time-varying predictors lower ADL/IADL scores, development of dementia and higher GDS scores were associated with higher AES scores over time (

Table 3).

Multivariate Models

When significant univariate time-varying (dementia, ADL/IADL, GDS) and index predictors (interval CVA) were combined into a multivariate model, dementia, ADL/IADL, and GDS, but not interval CVA, remained significant predictors.

Linear mixed-effect modeling was also applied to the control group. The result of the univariate and multivariate models are summarized in the

data supplement (Tables S4, S5). Gender and ADL/IADL were significant predictors for apathy in the control group.

Group-Based Trajectory Analysis

We tested three- to five-group models in linear and quadratic trajectories. The four-group model with linear trajectory was superior to three- and five-group models, based on consideration of both BIC (−1,458.04) and AIC (−1,439.89), as well as good representation of substantively distinct trajectories; hence, the optimal solution to data on Apathy score after stroke. The four-group model indicated three groups showing stable trajectories of Apathy over time, at distinct levels: Low Apathy (48%), Minor Apathy (29%), and High Apathy (12%); and one group showing a linear increase (11%), that is, a Worsening group.

Discussion

In this, the longest longitudinal study of apathy after stroke,

rates of apathy in patients increased steadily over 5 years, from 26.7% to 38.6%;

levels rose modestly, from 32.23 to 37.14, on the AES scale. These figures are likely to be underestimates, as there was higher attrition rates in those with apathy, consistent with the experience of Mayo et al.,

5 who reported that 478 out of an initial sample of 678 patients (65%) completed follow-up assessments through the first year. As expected, our patients had higher AES levels at Index and a steeper slope than community-based, dementia- and stroke-free control subjects, who themselves had increasing levels of apathy,

15 a finding recently confirmed in a larger population study.

34 Our findings differ from those from Mayo and colleagues, who reported an overall peak at 3 months after stroke and described several possible trajectories over the next 12 months. Reasons for these differences are discussed below.

Increasing apathy was mainly associated in univariate analyses with factors reflecting more brain pathology, such as worsening functional abilities, interval cerebrovascular events, and dementia diagnoses. When combined into multivariate analysis, the variables associated with apathy reflected cognitive and physical decline (dementia diagnosis and poorer ADL/IADL scores) and depression (as measured with the GDS). The relationship between apathy and depression is complex. Although measurement artifact could be a factor, with items such as lack of interest loading on both Apathy and Depression scales, we consider this unlikely, as the association between apathy and depression remained significant even when we removed these items from the GDS.

Increasing vascular pathology is the most likely cause of increasing apathy. In our previous report, we argued that cumulative vascular pathology might underpin both apathy and depression after stroke, since their overlap increases with longitudinal follow-up and increasing vascular pathology.

35 This has been further supported by a community-based study of 3,534 older community-dwellers in The Netherlands who were free of dementia.

36 The study found independent associations of stroke, other cardiovascular disease, and cardiovascular risk factors with symptoms of apathy; and, in an exploratory analysis of a subsample of 1,889 participants free of stroke and other cardiovascular disease, associations between apathy and systolic blood pressure, Body Mass Index, type 2 diabetes mellitus, and C-reactive protein.

36 Inflammation may also play a role, but others have not found an association between apathy and inflammation, based on measurement of C-reactive protein.

36There are both consistencies and inconsistencies between our study and that of Mayo et al.

5 Both studies identified Low, Minor, and High groups with stable trajectories, and a Worsening group based on their optimal trajectory models. Mayo’s study, however, also identified a linear Decreasing (i.e., improving) group, which we did not detect in our three-, four-, or five-group models. A five-group model was considered the optimal solution in Mayo’s study, whereas a four-group model showed best fit to our apathy data, when the same model fitting criteria (BIC, AIC) were applied. The variation might be partially due to the different time-frames of investigations and range of scores on AES. Mayo’s study focused on the apathy change over the first year after stroke and used six items, with scores ranging from 0–12, whereas our study was based on data of apathy change over 5 years, and used full AES, with scores ranging from 18–72.

Limitations

Limitations are the high rate of attrition (significantly through dementia and death) and missing data, with the resulting modest number of subjects and data not missing at random. We tried to account for these limitations by using a large number of imputations (N=20–1,000) and several significant predictors of attrition. Complete case analysis would possibly result in even higher bias; but even in the 45 patients who completed all AES ratings and who probably represent the least disabled patients, AES levels and rates increased over 5 years. Attrition is a major hazard in apathy studies, where motivation is lacking, which may explain the lack of published long-term studies. Thus, our findings are conservative, and rates and levels may be higher, especially given the link between apathy and mortality. Second, and importantly, the statistical analysis does not allow conclusions about causal relationships of the associated factors. Third, we note that use of a hospital-based sample cannot be generalized to community, non-admitted patients with stroke. Fourth, although we did not perform clinical interviews to diagnose cases of apathy, the AES has been validated against clinical diagnosis. Finally, we did not analyze the emotional/ affective, cognitive, and behavioral components of apathy or their associated pathology, which have been linked, respectively, to pathology in orbital–medial prefrontal cortex and related limbic regions within the basal ganglia (e.g., ventral striatum, ventral pallidum), dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, and the related subregions (associative territory) within the basal ganglia (e.g., dorsal caudate nucleus) and the associative and limbic territories of the internal portion of the globus pallidus.

37Implications

Implications for clinicians are the importance of recognizing apathy as a major and common aftermath of stroke, which is associated with poor outcomes for the patient. Its occurrence is likely to be associated with dementia and failing functional abilities.

12 Apathy can be readily overlooked because it places few obvious demands on professional caregivers, even though it is burdensome for family caregivers living with the person with apathy; it is associated with disability, and could hamper rehabilitation and reintegration. Importantly, apathy after stroke is more likely to worsen, rather than peak and then improve, yet its management has been little studied. As regards treatment, the statistically significant but modest benefits of some pharmacological strategies for apathy in people with dementia (see review

38) need to be weighed against possible adverse effects. Greater benefit may result from nonpharmacological strategies for treating apathy, such as use of therapeutic activities in patients with dementia.

39 It is not known whether these findings from studies of people with dementia and apathy are generalizable to post-stroke apathy, and future studies should investigate this.

We conclude that apathy after stroke is common and, contrary to a previous report, becomes more so with time, as cognition and function further decline. Given its reported association with poorer recovery, preventive and management strategies should be investigated.