Numerous empirical studies have demonstrated that optimism has benefits for physical health, emotional well-being, and longevity.

1 Empirical evidence from cross-sectional studies suggests greater optimism in older age.

2 Although the mechanism linking optimism to its many benefits is unknown, explanations include better emotional regulation among older adults with higher levels of optimism;

3 optimists’ tendency to use more effective, active coping strategies in stressful situations, such as problem-solving;

4 associations between optimism and internal locus of control;

5 and optimists’ tendency to engage in more positive health practices.

1 Regardless of the precise mechanism, optimists may live longer and healthier lives.

Despite the clear benefits of optimism on physical and emotional well-being, little is known about the neural correlates of optimism, and we know of no published reports using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to examine individual differences in optimism among older adults and how such differences relate to brain structure and function. Previously published reports assessing aspects of well-being other than optimism have demonstrated that, among older adults, increased thickness of prefrontal regions was associated with increased extraversion and less neuroticism.

6 Also, a recent fMRI study reported that higher self-reported life satisfaction (as measured by the Satisfaction With Life Scale [SWLS

7]) was associated with lower activation in prefrontal regions during the encoding of positive images.

8 Given that activation was assessed only for those items that were successfully encoded, the authors argued that lower activation might represent enhanced neural efficiency among older adults reporting higher satisfaction.

Processing of facial expressions is an important aspect of emotional behavior, and the abilities to identify and to discriminate among facial displays of various emotions are important components of emotion-processing and social communication.

9 Evidence from neuropsychology and neuroimaging studies suggests that emotional face perception involves a distributed network involving various regions, including the amydgala, fusiform gyrus, insula, orbitofrontal cortex, medial prefrontal cortex, thalamus, and occipitotemporal regions.

9 Studies examining age-related differences in the neural correlates of emotion-processing have found that, when compared with young individuals, older adults tend to activate frontal regions to a greater degree and the amygdala and fusiform gyrus to a lesser extent.

10–12 Despite growing research on both successful aging

13 and the neuroscience of social cognition,

14 there have been few studies integrating these fields to examine effects of aging on neural correlates of emotion-processing.

We chose to focus on processing of fearful faces and how that relates to individual differences in level of optimism. There are benefits to examining specific emotions, rather than global negative or positive affect, given that specific emotional dispositions differ in their influence on perception of risk and decision-making.

15 Dispositional optimism has been conceptualized as a personality characteristic involving generalized positive expectancies for the future.

4 Within this framework, a major component of optimism is expecting the best to happen in the future, and, conversely, a key part of pessimism involves expecting that the worst will happen. As such, optimists may be relatively less fearful, particularly about the likelihood of negative events (although evidence suggests that optimism is not identical to lack of worry in terms of predicting outcomes).

4Discussion

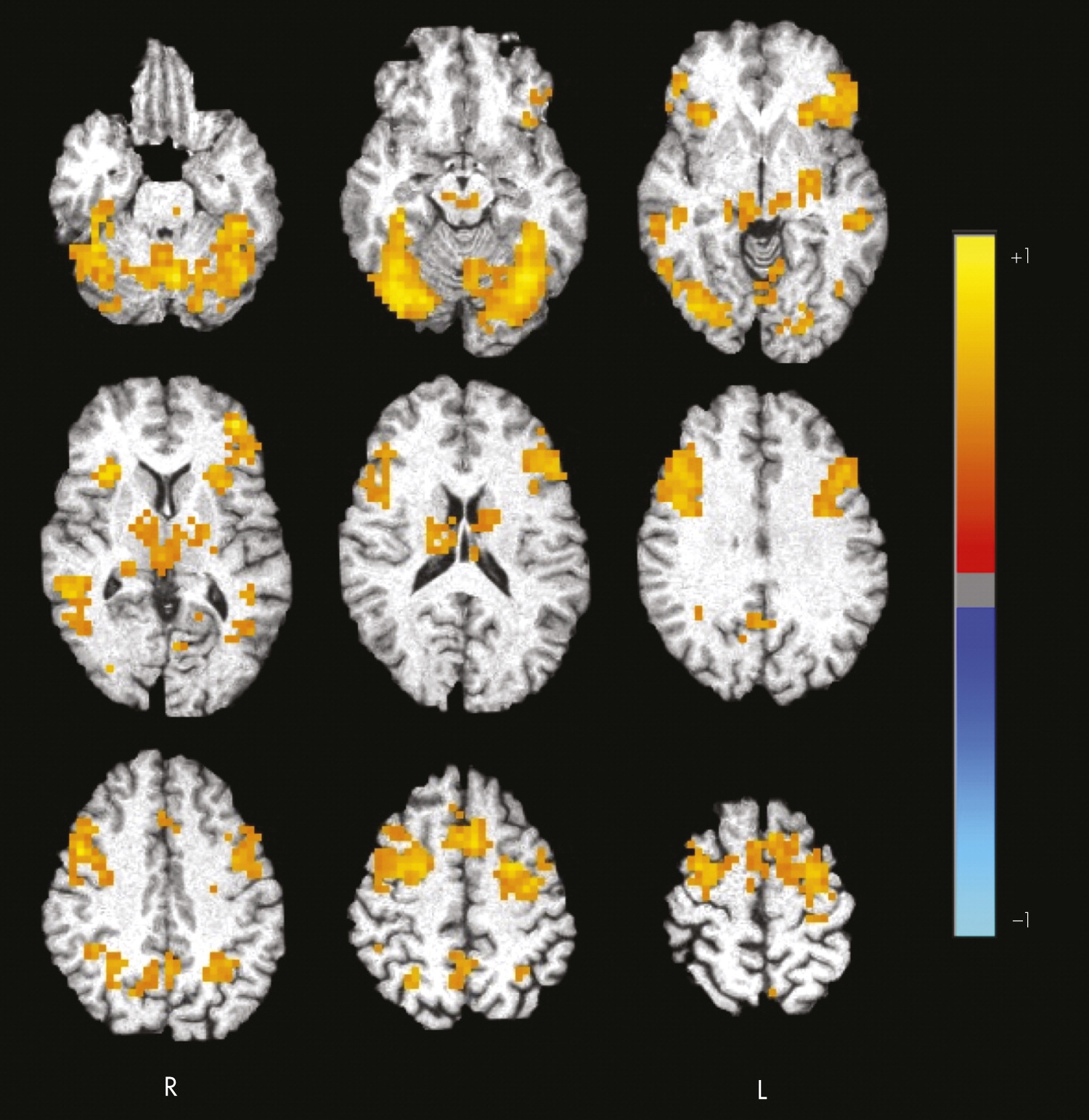

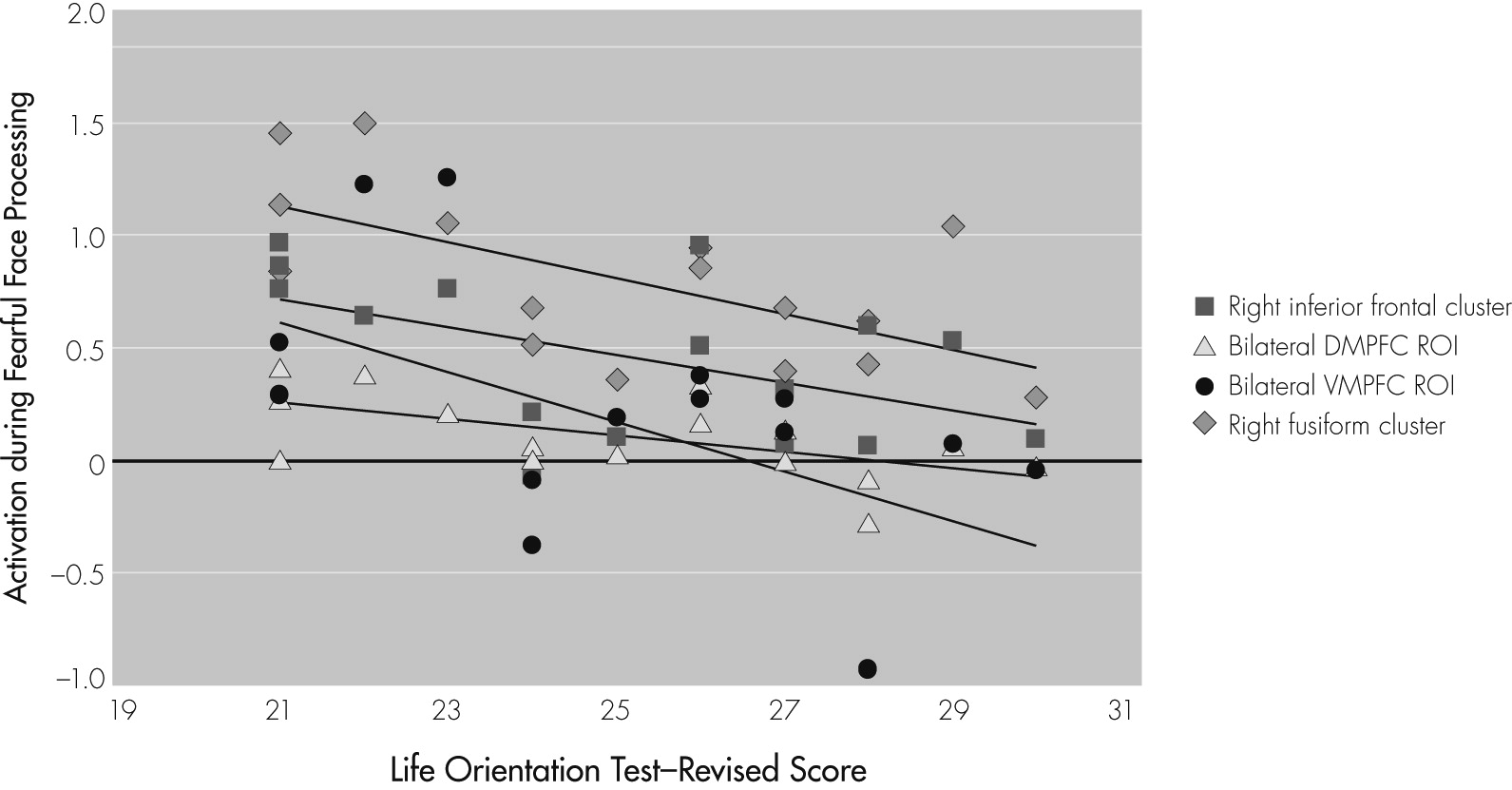

In summary, results support our two predictions related to the neural correlates of fearful-face processing and the association between task-related activation and optimism in older adults. First, during the processing of fearful faces, healthy older adults activated a widespread network, including frontal regions and fusiform gyrus. Additional analyses conducted using a priori ROIs based on previous literature implicating them in emotion-processing revealed positive task-related activation in the amygdala and dorsal medial prefrontal cortex. Second, greater optimism was significantly associated with decreased task-related activation in fusiform gyrus, inferior frontal gyrus, ventral medial prefrontal cortex, and dorsal medial prefrontal cortex. Optimism was not related to structural neuroimaging, resting CBF, fearful-face matching performance, demographic, or cognitive variables, suggesting that these factors may not be mediating the relationship between increased optimism and decreased task-related brain response.

The present findings are consistent with those of Waldinger and colleagues,

8 who reported that higher life satisfaction was correlated with lower activation in prefrontal regions during encoding of positive images. The authors interpreted these findings as reflecting greater neural efficiency in older adults with higher satisfaction. Reductions in neural activity are often observed on tasks measuring repetition priming.

27 Taken together, the observed pattern may represent optimistic individuals’ ability to process emotional items in a more efficient manner than their less-optimistic peers and without needing to engage prefrontal and fusiform regions to the same degree.

Other possible explanations for the results include the idea that optimistic individuals find negative information less salient; are better able to regulate their emotions; use more effective, active coping strategies in stressful situations; and tend to have an internal locus of control. As Waldinger and colleagues note, a discrepancy in salience of positive versus negative information in a subgroup of older adults would corroborate findings from behavioral studies, which have reported that older adults tend to remember positive rather than negative images

28 and to gaze toward happy faces and away from angry faces.

29 Furthermore, individuals with anxiety disorders have consistently been reported to demonstrate greater response during the processing of emotional stimuli within regions including the medial prefrontal cortex and amygdala.

30,31 It is possible that negative stimuli may be less salient; responses to them are better regulated; or more effective coping strategies are used, resulting in reduced task-related activation during the processing of fearful faces for optimistic older adults, a subgroup who have more positive expectancies for the future and who may be relatively less fearful themselves.

In the present study, amygdala activation was not detected during the whole-brain analysis and did not correlate with optimism level. The latter finding supports previous research reporting no link between task-related activation in the amygdala and well-being.

8 Although it is generally thought that the amygdala plays an important role in the processing of fear-related information,

32 it is also involved in vigilance

33 and relevance detection.

34 Fear-related stimuli may be less salient for optimistic older adults, resulting in either no or relatively little task-related activation during the processing of fearful faces for this subgroup of older adults. Of note, ROI analyses did reveal positive task-related activation in the amygdala, suggesting a small degree of activation that was not large enough to be detected during whole-brain analyses.

The present findings highlight the relationship between emotion-processing and optimism among older adults. In addition to its links with physical health, optimism has been linked to lower incidence of depression

35 and enhanced response to depression treatment among older adults.

36 Although the mechanism through which optimism influences mood remains unclear, there are several hypotheses, including optimistic older adults’ tendency to focus on positive expectations and future goals and thereby avoiding negative cognitive patterns; optimism is associated with improved coping, resulting in less depression, or a common biological cause involving neurotransmitters or genetic processes that may predispose individuals with low levels of optimism to depression.

36 Regardless of the precise mechanism or mechanisms, evidence suggests that as explanatory style becomes more optimistic, depression decreases.

37 Cognitive-behavioral therapy and other interventions aimed at enhancing optimism by focusing on developing more positive explanatory style and improving coping mechanisms as well as those targeted directly to enhance emotion-processing might have a potential to reduce mood symptoms. Furthermore, given the benefits of optimism not only on mood but also on other aspects of emotional well-being and physical health, such interventions may promote successful aging among older adults in general.

The present study has limitations. Our sample size was relatively small. However, our ability to demonstrate significant results despite a relatively small sample size suggests that these findings are likely robust. Second, our sample was somewhat homogeneous, which may limit generalizability of the findings to more diverse groups. Given that we intentionally recruited older adults who reported average-or-higher levels of optimism, there was little variability in optimism scores (i.e., optimism scores only ranged from 21 to 30 on a scale ranging from 0 to 32), resulting in a truncated range for statistical analyses. Nonetheless, we observed some important relationships despite this truncated range. Findings suggest that even within healthy individuals who range in optimism from average to above-average levels, variations in the degree of positive outlook are significantly related to the brain’s emotional processing response. Because of the strong association between pessimism and depressed mood, it is possible that the relationship between optimism and brain response to emotional processing might be obscured or might differ in individuals reporting higher levels of pessimism. A larger sample size and increased variability in optimism level may reveal additional relationships between optimism and brain response to emotional stimuli. Such findings may have important clinical implications. Finally, our use of multiple statistical tests might increase our rate of Type I errors.

In sum, the present study demonstrated that level of optimism was related to neural processing of emotional information among healthy older adults. Greater levels of optimism were associated with reduced task-related activation during emotional face processing in fusiform gyrus and frontal regions. This pattern of findings may reflect greater efficiency in neural processing, decreased salience of negative emotional information, better emotional regulation, more effective coping strategies, and/or an internal locus of control among optimistic individuals. These explanations are not necessarily mutually exclusive. It is possible that older adults with higher levels of optimism have less response to fearful stimuli, resulting in less perceived stress and a tendency not to get overwhelmed by stress or negative emotional information. This in turn may lead to better emotional and physical health. The present findings extend previous research in this area by administering standardized measures of emotional and cognitive functioning to more fully characterize participants, and examining the potential influence of age-related structural brain changes and resting hypoperfusion on results. Taken together, interventions aimed at enhancing optimism may have positive effects on mood, physical well-being, and emotion-processing among older adults. The present findings have potential implications for the elucidation, treatment, and prevention of conditions including late-life mood disorders and for the promotion of successful aging.