Epilepsy is usually defined as a disorder characterized by recurrent and unpredictable seizures.

1 It is not a singular disease entity or a static process. Epilepsies are a variety of disorders reflecting abnormal, excessive, hypersynchronous neuronal activity that is associated with substantial structural and neurochemical changes in the brain. Epileptic seizures have various manifestations and causes.

2 Clinical presentation of epilepsy may include perceptual, behavioral, cognitive, autonomic, and psychiatric symptoms.

3Epilepsy is associated with an increased risk for development of psychiatric disorder.

4 Furthermore, some psychiatric disturbances, such as mood, anxiety, psychotic, and dissociative states, are directly caused by epileptic conditions.

3 The mood changes include an abnormally elevated or depressed mood. Psychotic disorders involve hallucinations, delusions, or disorganized speech and behavior.

4 It is often difficult to describe the clinical features and to obtain a correct diagnosis in these cases.

Electroencephalography (EEG) is the most important diagnostic tool for investigating patients with clinically-suspected epilepsy. EEG abnormalities, which are seen as spikes, or sharp waves, spike and slow-wave complexes, polyspike, and slow-wave complexes, indicate epileptic seizures that are related to present psychiatric disorders.

5,6 However, the initial routine EEG sometimes cannot detect epileptiform activity. EEG under sleep-deprivation can increase the probability of detecting epileptiform discharges in such patients.

1,7A sleep-deprived-EEG procedure is required, keeping the patient awake for all or part of the previous night, with a longer period of EEG recording. In this study, two cases showing normal routine EEG but epileptiform discharges in sleep-deprived EEG conditions are presented.

Case #1

A 22-year-old man with complaints of social withdrawal, reduced amount of speech, fear of death, suspicion of family members, insomnia, forgetfulness, confusion, and absent-mindedness was referred to the psychiatry clinic of Dursun Odabas Medical Center. The patient stated that his symptoms had started about 2 years earlier after watching a horror movie. Symptoms have shown characteristic fluctuating and gradually increasing features, especially over the last few months, and persecutory delusions, auditory, and visual hallucinations were added to these complaints several days before admission. The patient had no history of substance abuse or a family history of mental disorders, but there was a family history of epilepsy. He had been admitted to several psychiatric outpatient clinics and had taken a variety of psychotropic drugs, such as fluoxetine and aripiprazole. Because of the continuation of his complaints, he had given up these treatments within several months.

On mental status examination; the patient was conscious, with normal orientation, but decreased self-care and prolonged reaction time. He gave short answers to the questions, and talked in a slow and low tone of voice, with decreased attention and concentration, circumstantial and tangential speech, ideas of reference, apathetic affect, dysphoric mood, depressive posture. Normal abstract thinking and reasoning and decreased appetite were observed. Guilt, shame, or suicidal thoughts were not noted.

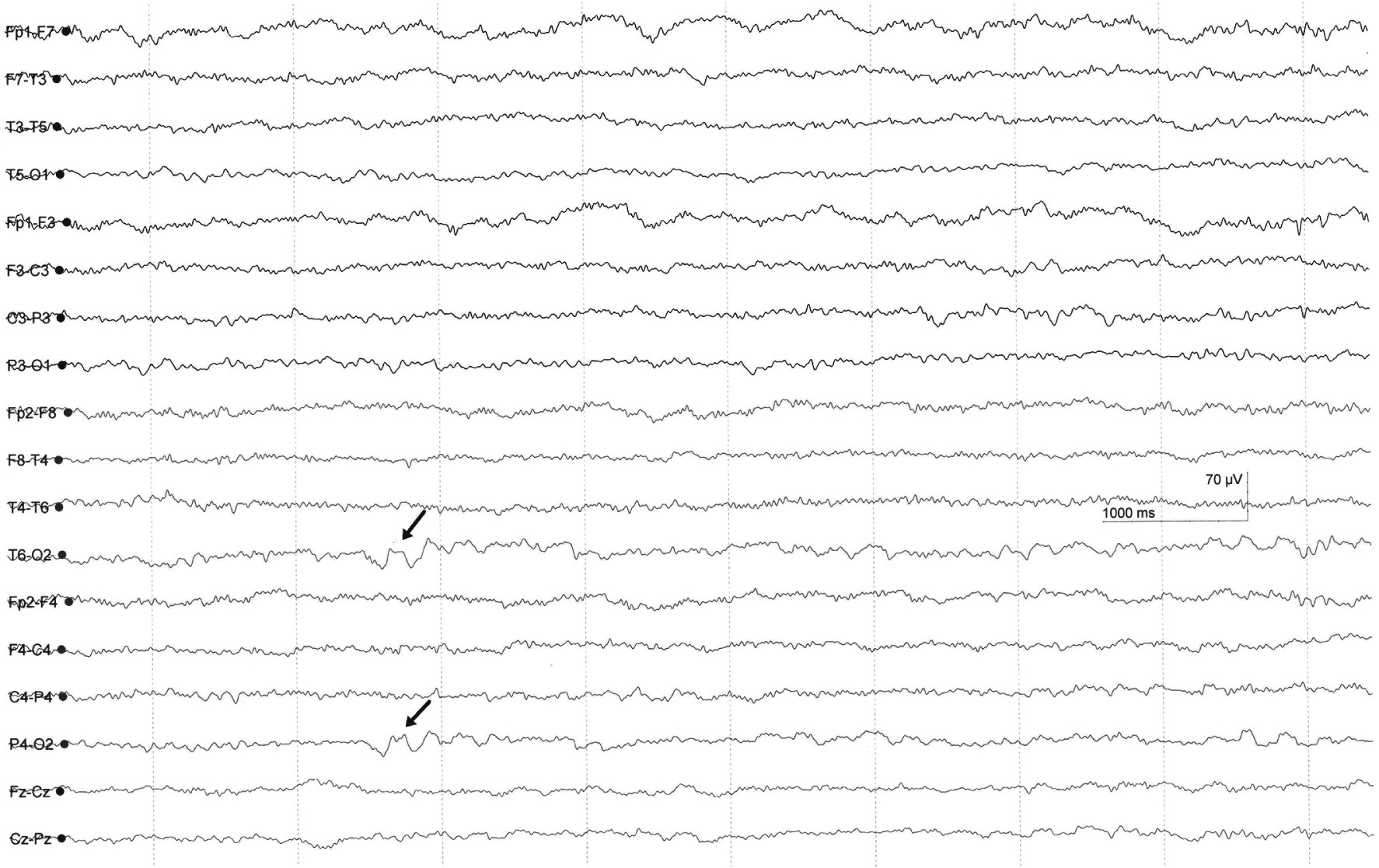

Because of the atypical clinical presentation, resistance to treatment, and a family history of epilepsy, routine EEG and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) were performed; these revealed no abnormality. Paliperidone 3 mg/day, escitalopram 10 mg/day, and psychotherapy were given for the treatment of psychotic and depressive symptoms. The dose of paliperidone was increased to 9 mg/day, and, later, to 20 mg/day after 1 week. After 1 month of treatment, because of the persistence of his symptoms, EEG under sleep-deprivation conditions was performed. Sleep-deprived EEG showed focal theta slow-wave paroxysms (4 Hz–5 Hz) in the right occipital region (

Figure 1). Carbamazepine 200 mg/day was added to the patient’s treatment and was increased to 600 mg/day until it reached the desired blood level. After this treatment, significant changes, including increased psychomotor activity, emotional expression, and amount of speech, were observed. Psychotic symptoms and confusion were also improved after antiepileptic treatment.

Case #2

“Ms. B,” 17-year-old young woman with complaints of talking when alone, inappropriate laughter or crying, spitting on herself, nervousness, excessive excitability, and insomnia lasting for 2 months, presented to the our outpatient clinic. She had displayed strange behaviors, such as beating her friends at school, throwing her clothes out of the window, spitting into clothes, burning them in the stove, and pulling down her pants at home. The patient had a history of vomiting and loss of consciousness after a severe head injury 7 years earlier.

On psychiatric examination, she was conscious, with normal eye contact, but poor self-care, impaired orientation for time, failing short-term memory, and poor attention and concentration; she had auditory, tactile, and olfactory hallucinations such as “insects walking in my hair;” “[I] hear noises that sound like ‘you are mad, maniac;’ ” “I get the smell of burnt food.” She showed accelerated speech, loosening of associations, emotional lability, and inappropriate smiling; bizarre behaviors, lack of insight, and decreased appetite and sleep were also reported.

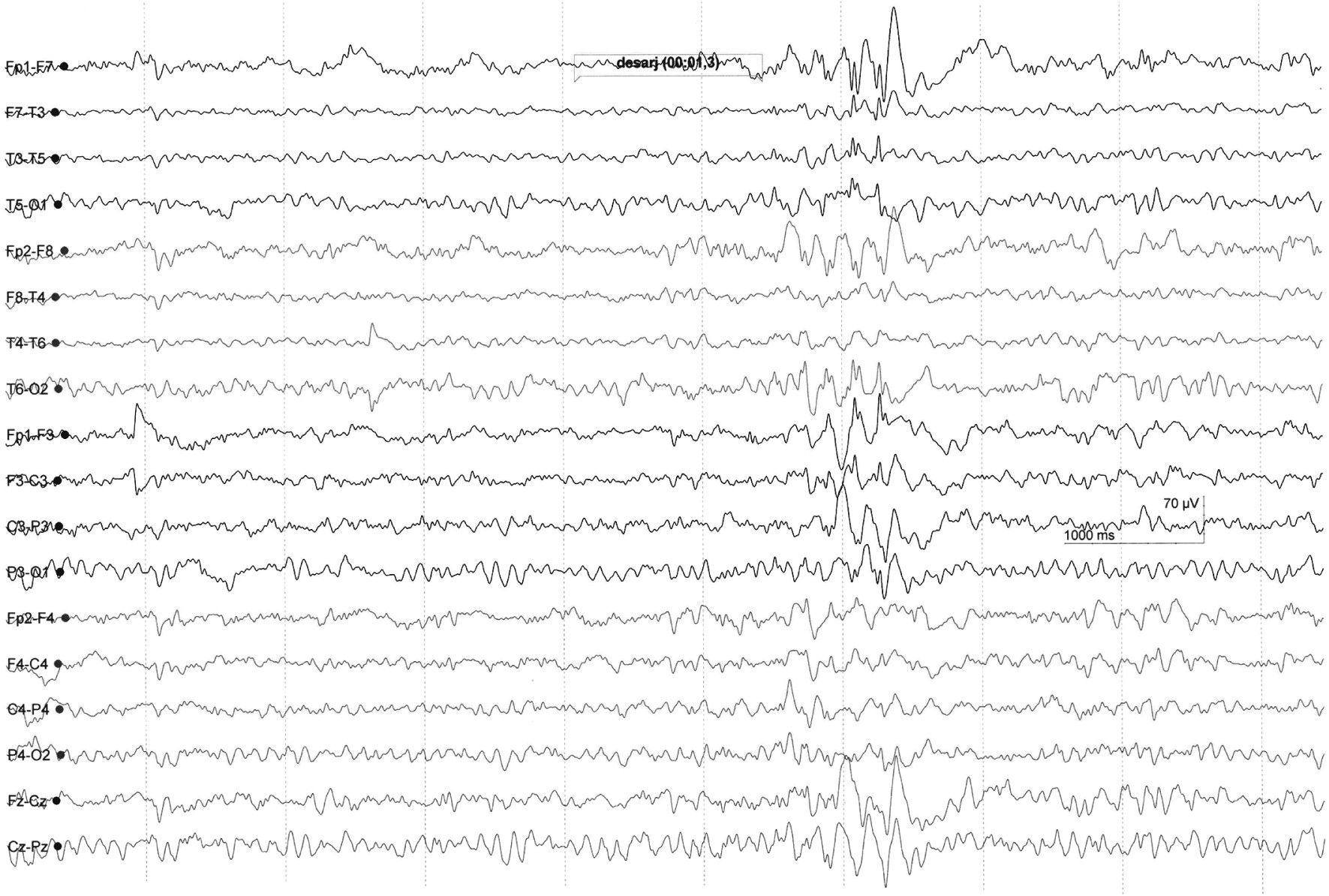

The existence of atypical psychiatric symptoms and history of head trauma suggested organic causes. MRI was normal. The routine EEG examination demonstrated only inter-hemispheric amplitude asymmetry. However, sleep-deprived EEG revealed generalized epileptiform activity, which was characterized by high-amplitude spike and wave discharges in anterior regions of both cerebral hemispheres (

Figure 2). The patient fully recovered with valproate 500 mg/day and risperidone 4 mg/day within 2 weeks.

Discussion

The causes of mental disorders are generally complex interactions and combination of biological, psychological, and social factors. There are many medical conditions, such as neurological disorders, infectious diseases, or endocrine problems that may induce psychiatric symptoms. Therefore, patients with psychiatric disorders require careful evaluation. Clinicians must be able to distinguish between organic and primary mental disorders for an appropriate treatment plan. Sometimes, accurate diagnosis may require advanced diagnostic methods.

Neurological diseases, especially epileptic seizures, can often cause symptoms of mental disorders such as depression, psychosis, or anxiety.

8 It is known that psychiatric manifestations of epilepsy may occur in both idiopathic cases and patients with seizures after a traumatic brain injury, as demonstrated in the above presented cases.

9 Psychiatric presentation of epileptic conditions is an important cause of misdiagnosis and, thus, the delay of proper treatment.

4 Clinically suspicious signs and routine EEG can assist in the differential diagnosis. Psychiatric manifestation of epileptic seizures include inattention, confusion, mood changes, bizarre behavior (inappropriate laughing, singing), and psychotic states.

4,8A routine EEG should be performed to support the diagnosis of epilepsy, but a normal EEG does not exclude the possibility of epilepsy.

1,3 If a routine EEG has been normal or has shown abnormal features that are not clear enough to make a definitive diagnosis, a sleep-deprivation EEG might help to determine the presence of epileptiform abnormalities. Moreover, routine EEG has low sensitivity for detection of epileptiform activity in deep structures, such as the limbic structures, hippocampus, and cingulate gyrus, which have an association with psychiatric disorders.

8,10The majority of the evidence supports the idea that sleep deprivation activates interictal epileptiform discharges. However, how sleep deprivation might activate epileptic regions is unclear.

11 McDermott et al.

12 reported that sleep deprivation affects behavioral and membrane excitability in hippocampal neurons, causes a lower membrane input resistance in CA1 pyramidal neurons, decreasing action potentials in response to depolarizing current, and also inhibiting long-term potentiation in both CA1 pyramidal neurons and dentate granule cells.

In conclusion, sleep-deprived EEG may be also useful for revealing organic electrophysiological dysfunction. Therefore, this method has been used for the differential diagnosis of mental disorders in the psychiatry clinic.

Acknowledgments

We thank Professor Temel Tombul for the analysis of EEG recordings.