There are currently no proven treatments for poststroke apathy. Ideally, treatment would begin soon after stroke, because apathy limits patients’ ability to participate in the intense rehabilitation programs typically offered only in the first months after stroke. To appropriately power trials in this period, we first need data on prevalence and natural history. Prevalence data are limited to patients with minimal cognitive and language deficits. A recent meta-analysis

4 reported that only two studies included patients with aphasia; of these studies, one only had five patients with aphasia

5 and the other did not use a formal measure of apathy.

6 Regarding natural history, published studies typically began at 1 month after the stroke, and these studies suggest that apathy is typically persistent and is associated with less recovery in activities of daily living and cognition.

3,7–9To determine how the severity of apathy changes in the first weeks after stroke, we prospectively studied patients admitted to an American acute rehabilitation unit for ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. We defined apathy based on clinician reports using the Apathy Inventory–Clinician (AI-C) version.

10 This scale is based completely on observed behavior, allowing us to include patients with aphasia.

On the basis of published studies of apathy prevalence in different periods after stroke,

1 we hypothesized that apathy severity would slightly improve during acute rehabilitation. We also sought to determine the relationship between poststroke apathy and depression. Finally, we performed secondary analyses to identify associations of apathy with other clinical factors such as aphasia, cognition, motor impairment, and rate of recovery from disability.

Results

We screened 257 patients who were consecutively admitted to Burke Rehabilitation Hospital with a diagnosis of ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. We excluded 161 of these patients based on criteria defined in the Methods, resulting in 96 patients eligible for this study.

Patients included in the study had a mean age of 72.8 years (SD=13.9), 38.5% were men, the median length of hospital stay was 24.5 days (interquartile range=13.5), and 15 patients (16%) had a hemorrhagic stroke. Nineteen patients (20%) had aphasia and thus were not testable with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and the Montreal Cognitive Assessment. Overall, patients were moderately disabled (mean admission FIM score=44.9 [SD=17.1]), and they were moderately weak (mean upper extremity Fugl-Meyer score=37.3 [SD=23.7], N=59; and mean lower extremity Fugl-Meyer score=21.3 [SD=9.4], N=65). Patients were also cognitively impaired (mean Montreal Cognitive Assessment z score=−1.11 [SD=2.0], N=76), with 26% of subjects 2 SD below the mean.

Apathy Severity

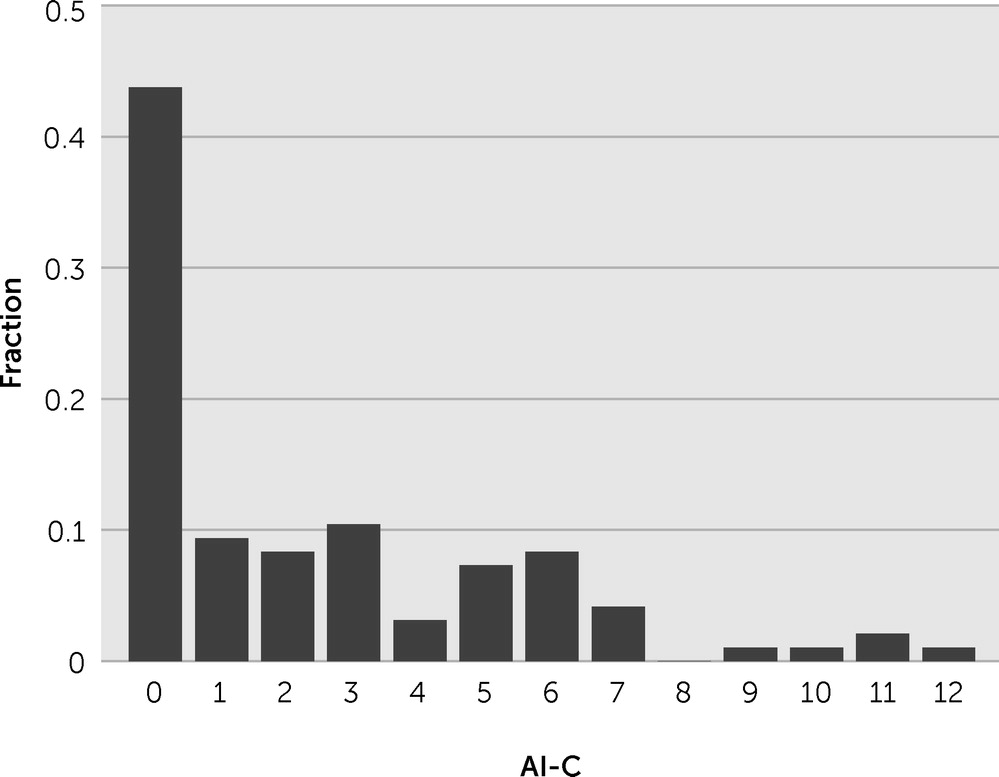

On the basis of the AI-C score from the treating speech-language pathologist, we found that 27 patients (28%) had apathy (AI-C score ≥4, with at least one of the three dimensions ≥2). Apathy severity was not normally distributed, because 42 patients (44%) had a score of zero (i.e., no signs of apathy) (

Figure 1).

We explored the relationships among the three subscores of the AI-C (emotional blunting, loss of interest, and loss of initiative) to determine whether patients presented with separate syndromes. We found that the scores generally correlated highly, because only seven of the 96 subjects had a subscore >1 point away from another subscore.

Change Across Time

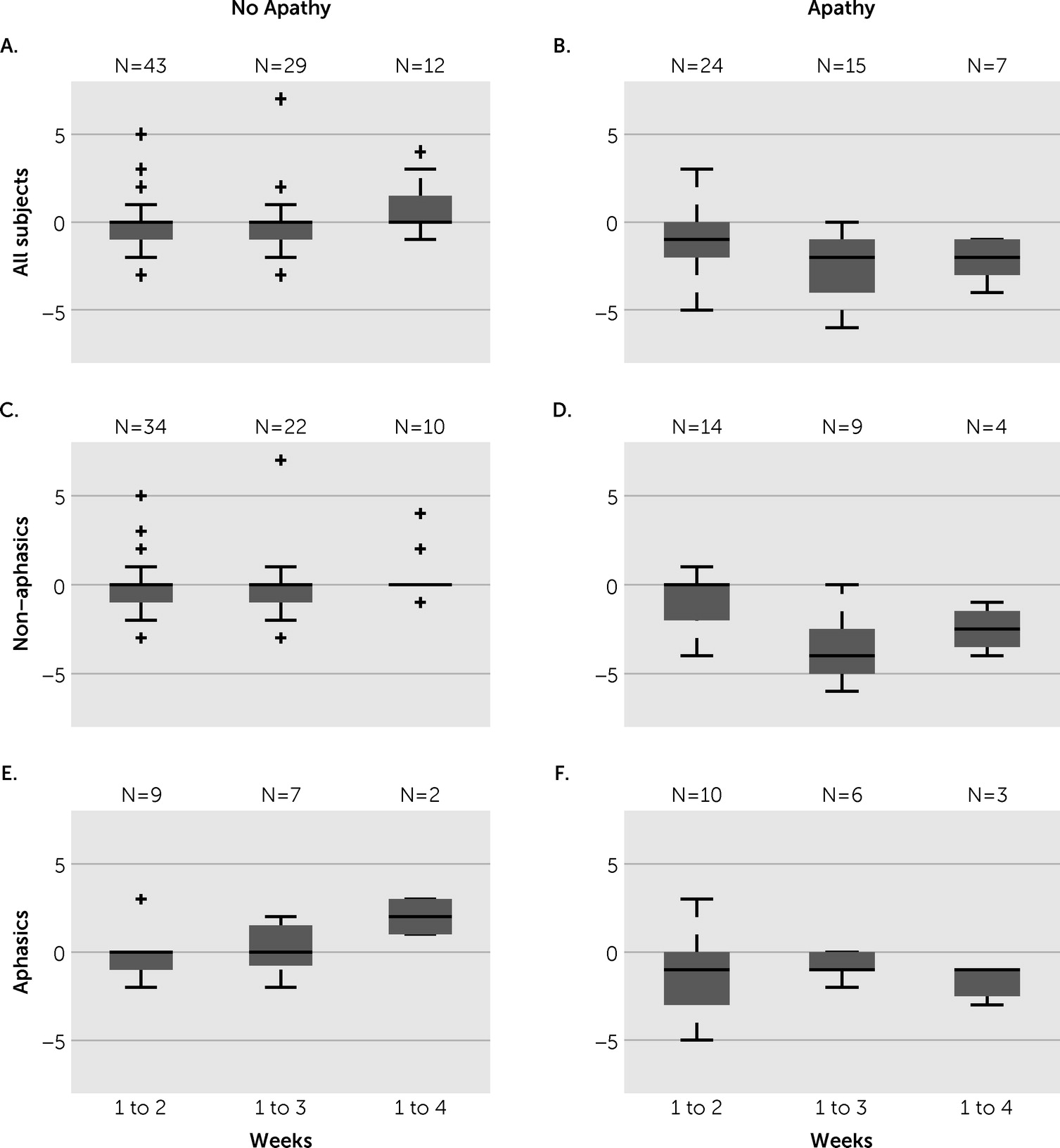

We documented apathy severity weekly, although patients had varied lengths of hospital stay; this resulted in fewer data points at the longer time durations. Patients without apathy at week one generally had no change in their apathy score over their stay (

Figure 2A), though some worsened slightly with five developing apathy at some point during their stay. Patients with apathy at week 1 (AI-C ≥4) typically demonstrated improvement in apathy severity, although this improvement was only to a small degree (

Figure 2B). Specifically, from week 1 to week 2, patients with apathy had a mean change of −1.04 (SD=1.73) in their AI-C score, with five of the 24 patients showing resolution of apathy (AI-C <4). From weeks 1 to 3, patients with apathy had a mean change of −2.40 (SD=2.03) in their AI-C score, with seven of the 15 patients showing resolution of apathy. From weeks 1 to 4, patients with apathy had a mean change of −2.14 (SD=2.03) in their AI-C score, with one of the seven patients showing resolution of apathy.

Correlations With Other Clinical Features

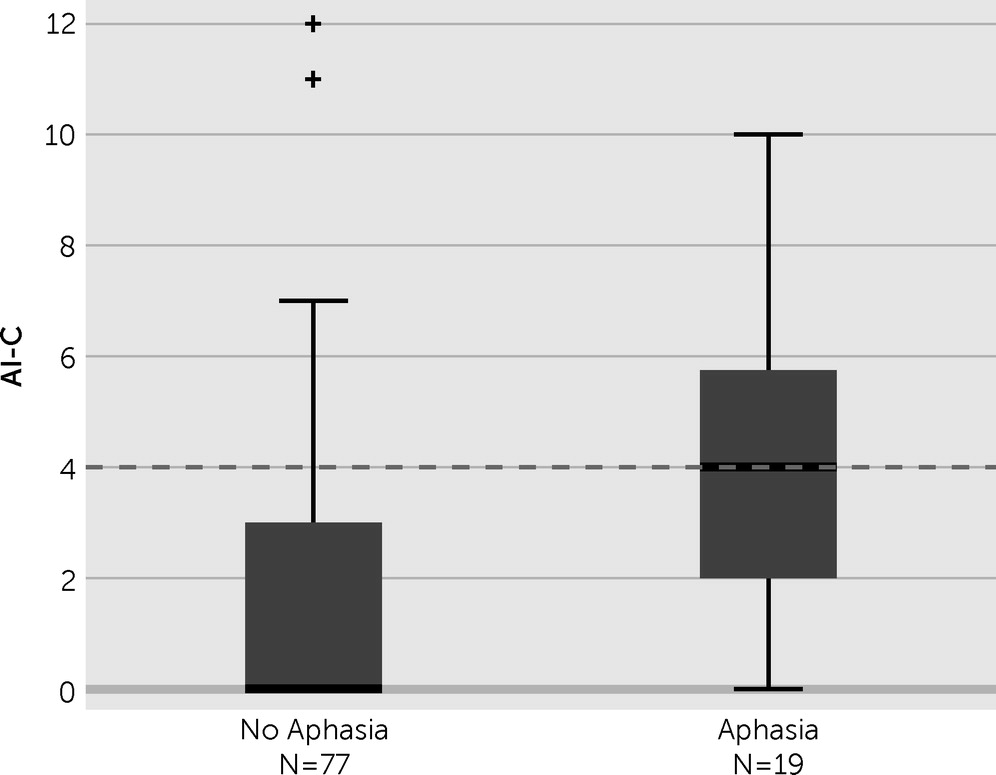

Aphasia correlated significantly with apathy severity (

Figure 3 and

Table 1). Using an AI-C cutoff value of 4 to define apathy, we determined that 10 (53%) of the 19 patients with aphasia were apathetic, whereas only 17 (22%) of the 77 patients without aphasia were apathetic. Regarding a change in apathy severity, patients with and without aphasia both showed a small degree of improvement during the first 2 weeks, but only the patients without aphasia improved during the subsequent weeks (

Figure 2, D and F). Patients with aphasia were also less likely to have resolution of apathy. In patients who stayed at least 2 weeks, seven of 14 patients without aphasia had resolution of apathy compared with only three of 10 patients with aphasia.

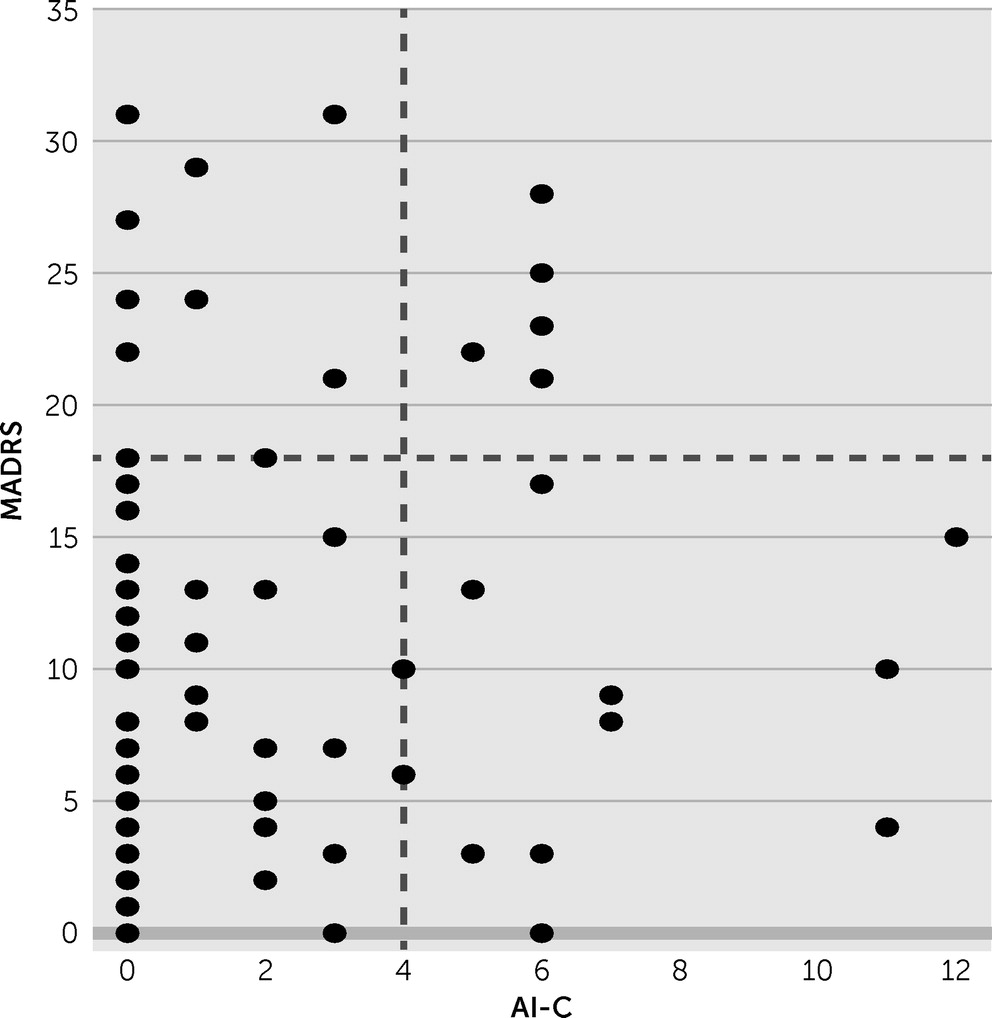

We measured depression severity using the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale in the 77 patients without aphasia. Based on a published cutoff value of 18,

19 15 (19.5%) of the 77 patients were depressed. We found no correlation between the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale and AI-C scores (

Figure 4 and

Table 1).

Regarding other clinical variables, apathy severity had a significant correlation with the following: overall cognition (Montreal Cognitive Assessment z score); disability (admission FIM score); change in FIM score from admission to discharge, whether measured directly or divided by length of stay (FIM efficiency); presence of neglect (line cancellation); and motor impairment (Fugl-Meyer score) at discharge (

Table 1). Patients with apathy were also more likely to go to a nursing home after discharge. Gender, age, days since stroke onset, and years of education did not have statistically significant associations with apathy severity.

Discussion

We found that apathy was present in 28% of patients undergoing inpatient acute rehabilitation for an ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke. We further found that apathy improved only modestly during the acute rehabilitation stay (a 1-point decrease by week 2 and a 2-point decrease by week 3) and the majority of patients with apathy remained apathetic at discharge. To our knowledge, this study is the first that assesses the change in apathy severity during the first few weeks after stroke and one of the few prevalence studies that include patients with aphasia.

Our prevalence of poststroke apathy is lower than that reported in the literature. In five studies of a similar time range after stroke (10–50 days), the mean prevalence of apathy was 36% (95% confidence interval, 30%−42%).

1 These studies excluded patients with aphasia; in our data set, patients without aphasia had a prevalence of 22%. Our finding of a lower prevalence of apathy may be attributable to the use of a different scale (the AI-C in this study versus the Apathy Scale used in most of the reported studies) and to our choice of a cutoff value of 4 points. Future studies would be better served by defining apathy based on consensus criteria,

20,21 rather than using arbitrary cutoff points on scales.

We found a markedly higher prevalence of apathy in patients with aphasia compared with patients without aphasia (53% versus 22%, respectively). We were only able to find one other study that included a significant number of patients with aphasia.

6 Carota et al.

6 studied 273 patients in the first days after stroke and found an overall apathy prevalence of 48%, with no difference in the 90 patients with aphasia. It is unclear why the results differed, although nurses in the study by Carota et al.

6 reported the presence of apathy, whereas speech-language pathologists in our study evaluated patients and used a validated scale. It is also unclear why patients with aphasia had a higher prevalence of apathy. This could relate to the lesion location or total lesion burden. Future studies would benefit from the inclusion of detailed imaging data.

Patients with apathy showed a slight improvement in apathy severity during the course of their stay in the rehabilitation hospital (2–4 weeks), although most patients with apathy at week 1 remained apathetic at discharge. The few studies that provide longitudinal data on poststroke apathy began assessment at least 1 month after stroke. Most studies found that apathy is rather stable during the 6–15 months poststroke,

3,5,7 although one study showed that apathy lasts on average for only 6 months.

8We found no correlation between apathy severity and depression severity in the subset of patients who were tested with the Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale, which requires intact language. Previous studies have reported both significant and nonsignificant associations of these conditions.

1 The inconsistency in the literature may be attributable to the variety of scales used to assess apathy and depression, many of which have overlapping questions. In our study, the apathy measure was based solely on observed apathetic and not dysphoric-type behaviors, although our depression measure (Montgomery-Åsberg Depression Rating Scale) does include two self-report measures linked to apathy (lassitude and inability to feel).

We also found that apathy severity correlated with impaired cognition (Montreal Cognitive Assessment score), disability (FIM score), neglect (line cancellation), and weakness (Fugl-Meyer score). Associations between apathy and worse cognition have been a relatively consistent finding in the apathy literature.

1 Most studies also found a similar association between apathy and increased disability, although they varied in methods of assessment.

1 Our study also confirmed our previous finding that patients with worse apathy severity are more likely to be discharged from the inpatient rehabilitation hospital to a nursing home, rather than to their home.

2 Overall, these associated symptoms of poststroke apathy suggest that treatment of apathy may improve outcomes in a variety of domains

22; however, with our correlational data, it is not possible to dissociate the effect of apathy from severity of stroke.

This study has some limitations. First, it is challenging to measure apathy in patients with aphasia because language is typically our best insight into a patient’s goal-directed cognition and emotion. We attempted to ameliorate this by asking the evaluating speech-language pathologists to comment on nonverbal communication by the patients. In addition, we did not measure the presence of apathy before stroke, so it is possible that some of our patients had apathy as a lifelong personality trait. A final limitation is that our study lacked a test of interrater reliability of apathy severity. We attempted to conduct a test of reliability between speech-language pathologists who saw their own patients compared with the speech-language pathologists who saw the patients in a group therapy session; however, our pilot work showed that patients’ level of motivation and affect varied between the two settings and thus could not be an accurate test of interrater reliability.

In summary, we found that apathy is common in the first weeks after stroke in patients undergoing acute rehabilitation, and shows only a small degree of improvement during this period. We further found that apathy is associated with worse cognitive dysfunction, neglect, aphasia, worse motor function, more overall disability, and a slower rate of recovery. Clinically, these findings suggest that we should follow up on patients with apathy, especially those with more severe apathy, because they typically do not improve and would likely benefit from treatment. Our results also indicate that the acute rehabilitation setting is ideal for conducting clinical trials for poststroke apathy treatment because apathy is common, is associated with poor outcomes, and shows only a small degree of spontaneous improvement.