Restless legs syndrome (RLS) is a common neurosensory motor disorder characterized by an irresistible urge to move one's body, most commonly the legs, usually with uncomfortable sensations that worsen at rest and at night.

1 Periodic limb movements during sleep (PLMS), formerly sleep myoclonus,

2 consist of brief involuntary movements of the foot and legs during sleep, often associated with sleep disruption. Clinically, RLS and PLMS frequently co-occur,

3–5 and a potential etiologic association between them has been frequently attributed to these conditions because both RLS and PLMS reliably respond to dopamine agonist treatment.

6–8 In fact, many practitioners assume that the frequency of individual movements throughout the night, commonly quantified in the Periodic Limb Movement Index (PLMI), correlates to the severity of RLS symptoms. Several pivotal trials previously have utilized reduction in polysomnography-measured PLMI as a proxy for objective clinical outcome.

9,10However, clinical association between severity of RLS and PLMS remains controversial. For example, Aksu et al.

11 and Garcia-Borreguero et al.

12 reported that PLMI is associated with severity of RLS symptoms. In contrast, a larger sampled study by Hornyak et al.

13 found no correlation between RLS severity and either PLMS-arousal index or PLMI among two groups: untreated RLS outpatients at a sleep disorders center and participants of the Pergolide European Australian RLS study. Furthermore, while the presence of PLMS is highly prevalent among RLS patients, a substantial minority of RLS patients (up to 20%) reportedly do not have PLMS.

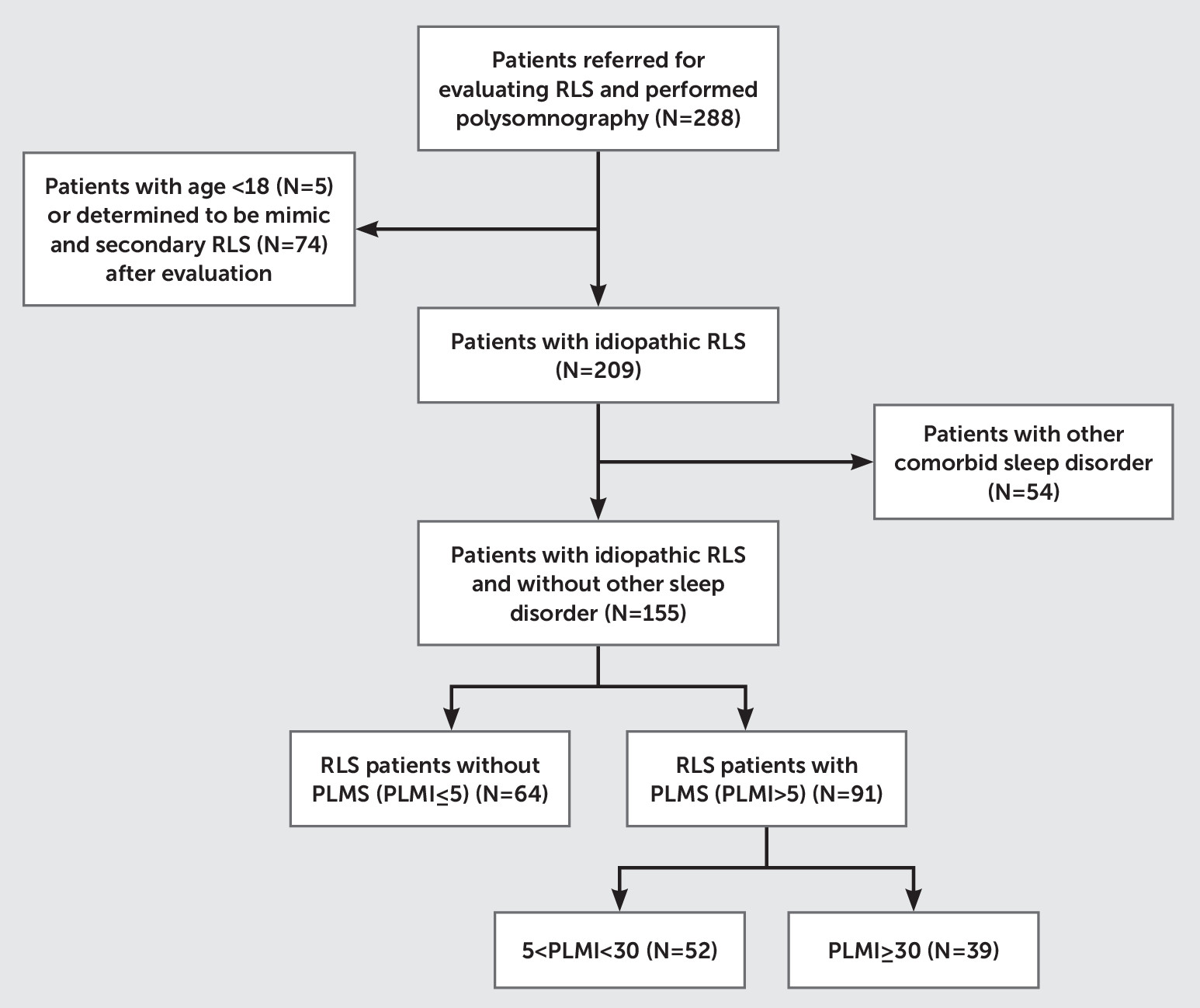

5,8Therefore, based on a large clinical database of untreated RLS patients, we selected and stratified untreated, idiopathic RLS patients into three groups on the basis of the presence and severity of PLMS and examined whether severity of PLMS was associated with RLS symptom severity and RLS-related quality of life. Furthermore, based on the previous study by Baumann et al., we hypothesized that RLS subjects without PLMS would have higher depression and anxiety ratings on standardized measures than RLS subjects with PLMS. By comparing polysomnography (PSG) and clinical characteristics among RLS patients with and without PLMS, we aimed to determine whether there are distinct clinical features that make subtyping RLS without PLMS clinically significant.

Discussion

In our study sample of idiopathic RLS patients, we found that presence of PLMS is not associated with subjective sleep quality, RLS severity, and quality of life. We also found that PLMI is associated with RLS severity only in RLS patients with more severe PLMS (PLMI >15). Furthermore, lack of PLMS appears to be associated with significantly higher depression and anxiety among RLS patients, and RLS patients without PLMS had distinct PSG parameters such as lower total arousal index, longer latency to REM, and a higher spontaneous arousal frequency than RLS patients with PLMS.

Interestingly, in our study, the proportion of those without PLMS (PLMI <5) was 41%, which is higher than previously reported.

5 Unlike many previous studies, we carefully selected for idiopathic untreated RLS patients (N=155) by excluding a large number of patients with secondary causes of RLS (N=74) and those with comorbid sleep disorders (e.g., obstructive sleep apnea [RDI ≥5]: N=48), in whom PLMS is very common.

29,30 In a large community-based, multiethnic epidemiologic study, PLMS was reported to be less prevalent in Chinese Americans compared with Caucasian, Hispanic, or African Americans.

31 By extension, East Asians with RLS may have lower prevalence of PLMS than Caucasians with RLS. Also, in our study, subjects in both the mild and moderate-to-severe PLMS groups were significantly older and more likely to be male than RLS patients in the no PLMS group. This is consistent with previous reports of higher prevalence of PLMS among the elderly

32,33 and in men.

11,34,35 Nevertheless, the high prevalence of RLS without PLMS in our carefully characterized clinical sample questions the presumed etiologic linkage between RLS and PLMS for a substantial portion of RLS patients and strongly suggests an independent pathophysiology for this subgroup of RLS patients.

Subjective sleep measures (PSQI-K, ISI-K, and ESS-K) seemed to be similar across the three groups when stratified based on PLMI. In other words, presence of PLMS in RLS does not seem to have much clinical impact on subjective sleep-related symptoms. However, we found a significant correlation between PLMI and severity of RLS only in RLS subjects with PLMI >15. Previously, there have been conflicting reports about the correlation between severity of RLS and PLMI among RLS patients,

11–13 and inclusion of RLS subjects without PLMS in previous studies might have led to inconsistent results. Also, our findings suggest potentially overlapping etiologic association between RLS and PLM only among RLS patients with more severe PLMS, but not among RLS patients without PLMS. Clinically subtyping RLS without PLMS and analyzing the RLS subjects separately based on presence of PLMS might lead to more consistent, replicable findings in future studies on etiopathogenesis of RLS.

Another distinct finding was the high prevalence—nearly two-thirds (65.1%) based on HADS-K and almost half of the group (49.2%) based on K-BDI-2—of clinically significant depression in the no PLMS group. Our findings are consistent with a previous report by Baumann et al. that restless legs symptoms without PLMS seem to have higher rates of psychiatric comorbidities than RLS patients with PLMS.

36 Depression and anxiety have been previously noted to be common among RLS patients in the community and in specialty clinics.

37–39 Our study indicates that this subgroup of RLS patients without PLMS seems to be disproportionately at risk for clinical depression. This warrants careful evaluation of mood symptoms, as the presence of depression has a greater negative impact on health-related quality of life than sleep disturbance or duration of RLS.

40 This finding is especially pertinent for RLS patients in South Korea, where mental disorder and psychiatric treatment remain highly stigmatized. Despite high levels of depression and anxiety, none of the participants in our study were receiving psychiatric treatment or under the care of a psychiatrist.

A recently published study also reported that RLS patients who complain of painful sensations had more severe anxiety and depressive symptoms but had lower PLMI than patients without painful RLS.

41 Unfortunately, we do not know whether painful RLS—asthenia crurum dolorosa—was more common in the no PLMS group than in the other two PLMS groups. Future study should closely examine whether PLMS status has any bearing on the pain-depression relationship in RLS. Perhaps the original description of RLS by Karl-Axel Ekbom in 1945, which describes two types of RLS, asthenia crurum paresthetica and asthenia crurum dolorosa, might have implications on etiopathophysiology of RLS.

42Furthermore, there were several differences in objective sleep measures among the three groups. Notably, the no PLMS group had significantly longer latency to REM sleep, higher spontaneous arousal index, and lower total arousal index compared with the two PLMS groups. Investigation of REM latency in depression and anxiety has a long history. Shortened REM latency in depression

43 and, to a lesser degree, delayed REM latency for anxiety

44,45 have been reported and studied as potential biological markers for these states. Previously, Brand et al.

46 compared latency to REM between RLS patients with and without depressive symptoms and found no difference, but the same study reported that REM latency in RLS patients was significantly longer than in major depressive disorder patients without RLS. Hornyak et al.

47 also reported that RLS patients had longer latency to REM compared with normal controls. In our study, despite high prevalence of clinical depression, the no PLMS group had the longest latency to REM sleep. From these results, we can make an inference that, unlike idiopathic depression, depression in RLS is not associated with REM latency, while degree of PLMS is associated with REM latency in RLS.

Predictably, the no PLMS group had a significantly lower PLM arousal index and total arousal index compared with the two PLMS groups. Alternatively, the no PLMS group had a significantly higher spontaneous arousal index than either of the two PLMS groups. Increased sleep fragmentation and arousals have been previously reported among depressed patients, and sleep continuity disturbances are concomitant, prodromal, and residual symptoms of major depression that subside on depression remission.

48,49 In our study, higher levels of depression in the no PLMS group may have led to an increased spontaneous arousal index in the no PLMS group, and future study should investigate whether improved sleep continuity results in amelioration of either depression or RLS symptoms among RLS patients without PLMS. A recent analysis by Szentkiralyi et al. based on two prospective cohort studies reported that clinically relevant depressive symptoms (CRDS) might be a risk factor for RLS, and the same study found that RLS at baseline, to a lesser degree, was also an independent risk factor of incident CRDS. Findings were similar in another longitudinal study of the Nurses’ Health Study cohort by Li et al., suggesting a bidirectional relationship between depression and RLS.

50,51 In order to elucidate the potentially overlapping biological mechanism underlying the association between depression and RLS, further studies should be carried out to examine and compare the pathophysiological characteristics between RLS with and without PLMS.

A major strength of our study is that it is the first study to compare clinical and PSG characteristics in a carefully characterized group of clinical RLS patients with and without PLMS, based on previously validated instruments and standardized PSG methods. Limitations of our study include the cross-sectional study design, which makes it difficult to draw conclusions about direction of causality among the variables. We employed single overnight PSG, which does not account for night to night PLMS variability within an individual. Also, we did not assess the qualitative aspects of the sensory symptoms (e.g., pain) of RLS patients that might have influenced their mental health ratings.

In summary, RLS without PLMS is associated with high levels of anxiety and depression and has several distinct PSG characteristics. Bauman et al. reported that patients with restless legs symptoms without PLMS tend to be treatment-resistant to dopaminergic therapy.

36 In the future, clinical outcomes of patients with RLS without PLMS should be compared with patients with RLS with PLMS to see whether absence of PLMS is a predictor of treatment response for a specific RLS or depression therapy. Along with distinct clinical and PSG characteristics, differential response to treatment in RLS without PLMS could pave a way toward future research to identify divergent biological pathways underlying etiopathogenesis of RLS without PLMS versus with PLMS.