Late-life depression has been extensively investigated; however, less is known about anxiety in old age. Yet, subsyndromal symptoms of anxiety are prevalent in the elderly, with a reported 12-month prevalence rate of 26.2% for subthreshold anxiety, versus 5.6% for DSM-IV anxiety disorders.

1 In addition, subsyndromal symptoms of anxiety are associated with poor outcomes such as cognitive decline,

2 increased health care cost, and reduced health-related quality of life.

3 Experts have recently suggested conceptualizing anxiety in late life as a dimensional rather than categorical construct.

4 Based on this concept, it is crucial to investigate symptoms of anxiety rather than anxiety disorders. In addition, a National Institute on Aging and Alzheimer’s Association expert panel has called for characterizing and understanding the presymptomatic phase of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) by using biomarkers such as brain MRI.

5 Investigating the association of subsyndromal anxiety with biomarkers in presymptomatic AD will be a value-added approach toward an understanding of presymptomatic AD.

Changes in cortical thickness have been observed in normal aging, mild cognitive impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s disease dementia,

6 and also in psychiatric disorders, including major depression

7 and anxiety.

8 An automated method has been developed to accurately measure cortical thickness across the entire brain, providing an opportunity to investigate the structural correlates of anxiety.

9 Only few studies have examined cortical thickness in participants with anxiety disorders

8 or symptoms.

3,10 Most reports were based on small sample sizes and involved a wide age range, with mostly middle-aged participants.

We therefore sought to examine the associations between anxiety symptoms and cortical thickness in elderly community-dwelling participants. In addition, we performed further analyses also adjusting for depressive symptoms. Furthermore, we investigated the association between anxiety symptoms and the amygdalar, as well as hippocampal volume.

Results

The complete demographic characteristics are presented in

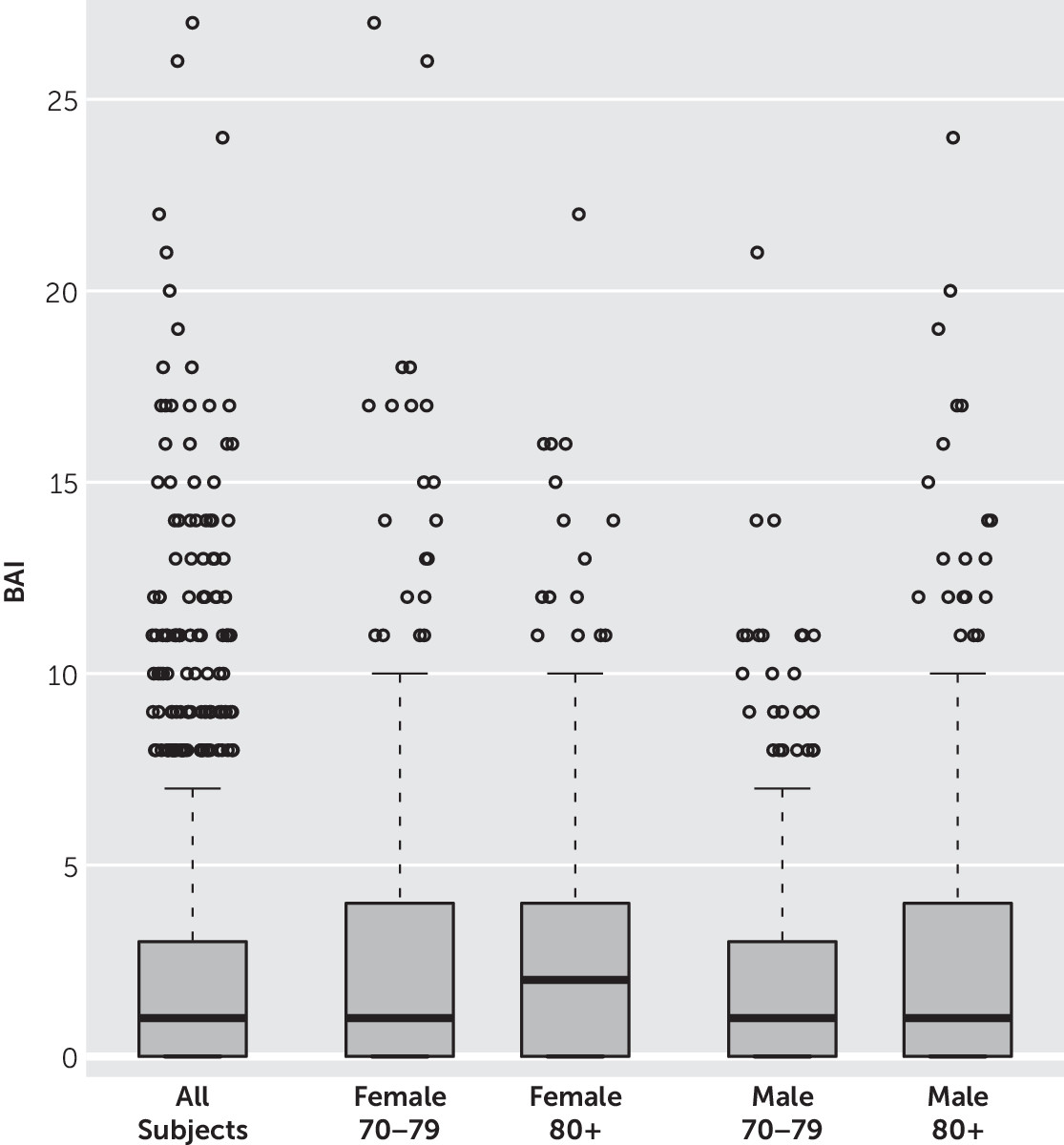

Table 1. Only a small percentage of this population-based study met the threshold for clinical anxiety (BAI >10; 5.3%) and depression (BDI >13; 5.6%). Participants with anxiety symptoms were significantly older, had fewer years of education, lower scores on the Short Test of Mental Status,

34 lower z-scores for global cognition, higher number of depressive symptoms, and higher use of antidepressant medication compared with participants without anxiety symptoms.

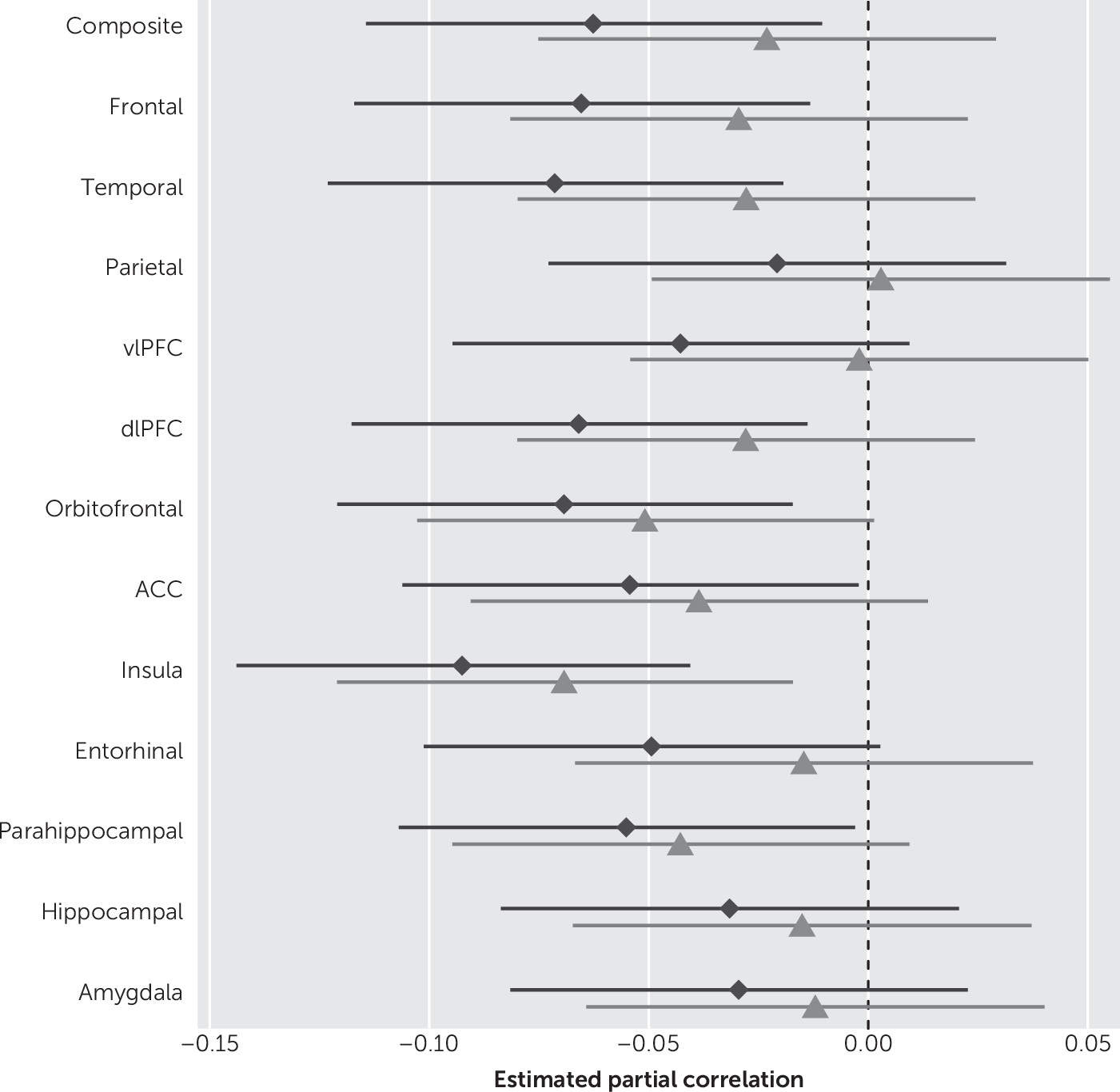

When examining anxiety symptoms as a continuous variable, we observed associations with reduced thickness in most ROIs in unadjusted models (

Table 2). In multivariate analyses, the higher the BAI scores the lower the cortical thickness of the ROI, noted as follows: global/composite thickness (r=−0.06, p=0.02), frontal (r=−0.07, p=0.01), and temporal (r=−0.07, p<0.01), DLPFC (r=−0.07, p=0.01), insula (r=−0.09, p<0.01), parahippocampal (r=−0.06, p=0.04), and ACC (r=−0.05, p=0.04), after adjusting for age, sex, education, medical comorbidity, antidepressant medication, and global cognition. When we additionally adjusted for depressive symptoms (as measured by BDI-II), only the associations between anxiety symptoms and reduced insular cortical thickness remained significant (r=−0.07, p<0.01). We further observed a correlation between OFC with anxiety that nearly reached statistical significance (p=0.06) after correction for depression. A secondary analysis did not show associations between anxiety symptoms and amygdalar or hippocampal volume, after adjusting for age, sex, education, medical comorbidity, global cognition, and antidepressant medication use (

Table 2).

Figure 1 shows forest plots of the partial Spearman rank-order correlations, and

Figure 2 shows a boxplot of the BAI scores by sex and age groups.

Discussion

Herein we report the associations between cortical thickness and anxiety symptoms in a large sample of cognitively normal elderly participants enrolled in the population-based Mayo Clinic Study of Aging. In previous studies, we and others have shown that anxiety symptoms increase the risk of developing mild cognitive impairment in cognitively normal elderly participants. This may indicate that anxiety symptoms could be a marker of preclinical AD. Thus, we looked at elderly participants who were still free of MCI and dementia. We then sought to examine whether there was already a structural correlate to anxiety symptoms. However, since these are cross-sectional data, whatever is reported about structural biomarker relationships is not yet answering this question of preclinical AD indicators.

We observed associations between anxiety symptoms and lower global thickness, as well as lower thickness in frontal and temporal cortical regions, after adjusting for age, sex, education, medical comorbidity, antidepressant medication, and global cognition. The results changed markedly after we additionally adjusted for depressive symptoms. Furthermore, as expected, the effect sizes were very small. In contrast to patients from clinical settings, we randomly sampled and recruited participants from the general population with the result that participants had very mild symptoms of anxiety. Only a small percentage of this population-based study met the threshold for clinical anxiety (BAI >10; 5.3%).

Several studies have examined associations between brain volumes and disorders of anxiety, based on categorical classifications, for example, generalized anxiety disorder or panic disorder. They mainly reported altered volumes of the amygdala,

11,12,35 insular cortex,

13,35–37 and ACC.

10,36,37 Few studies also reported altered volumes in the prefrontal cortex

3,10,12 and temporal regions.

12,38,39 However, little is known about the association between cortical thickness and anxiety symptoms in the elderly. Moreover, most previous studies that examined anxiety did not specifically adjust for comorbid depression. Yet, our study findings changed markedly after additionally adjusting for depressive symptoms. While the associations with various regions remained in the same direction, only the association between anxiety symptoms and reduced insula thickness remained statistically significant and the association between OFC with anxiety remained marginally significant after additionally adjusting for depressive symptoms. This finding suggests that many regions that appear to be associated with anxiety could be rather confounded by the presence of co-occurring depressive symptoms. Indeed, our data suggest that only insular thickness may specifically be associated with anxiety symptoms. This is in line with previous studies that have shown an association between reduced insular volume and disorders of anxiety.

13,35–37 The role of reduced insular thickness in anxiety symptoms may be explained by the insula’s high interconnections with other cortical and subcortical regions. Moreover, the insula has been shown to be involved in emotional response, and its size and reactivity have been linked to awareness of bodily responses, and especially anxiety.

40We observed no relationship between anxiety symptoms and hippocampal or parahippocampal MRI measures. This may indicate that anxiety may not be a valuable predictor for AD risk in the subclinical stages of AD. The amygdala is probably the most widely investigated region in anxiety,

3,11,35 and several studies have reported associations between reduced amygdalar volume and anxiety disorders.

11,12 We only observed significant associations in our unadjusted results. However, similar to other studies that investigated mild anxiety symptoms,

2,10 we also did not observe significant associations between amygdalar volume and very mild anxiety symptoms in community-dwelling participants after adjusting for multiple possible confounders. This may indicate that in contrast to studies that reported significant associations with clinical anxiety disorders, mild symptoms in community-dwelling individuals may not be severe enough to manifest associations with lower amygdalar volume.

Additionally, we conducted further analyses in order to explore correlations among the components of neuronal circuitry related to anxiety. Indeed, we observed significant correlations between the insular cortex and orbitofrontal cortex (r=0.54, p<0.01), as well as between the insular cortex and amygdala (r=0.08, p<0.01). This finding is consistent with previous reports.

10Investigators from Italy examined associations between anxiety symptoms, as measured by the Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, and amygdalar and hippocampal volume, as well as cortical thickness, in the OFC and ACC in 121 participants with a median age of 36 years. While, similar to our findings, they did not observe reduced amygdalar or hippocampal volume; they also reported associations between anxiety scores and increased ACC thickness.

10 Whereas they and others reported increased thickness,

2,9,36 other studies have reported reduced ACC volume in individuals with panic disorder.

36,37 We observed weak associations between reduced ACC thickness and anxiety symptoms, as measured by BAI, after adjusting for age, sex, education, medical comorbidity, antidepressant medication, and global cognition. Discrepancies across studies may be attributable to methodological issues, including differences in anxiety assessment and participant age groups. Since age is associated with reduced cortical thickness,

41 it is possible that studies involving younger individuals may show different results and that associations between anxiety symptoms and lower cortical thickness do not manifest until old age. While the mechanisms that may underlie reduced cortical thickness are not fully understood, it has been reported that the neuronal number is not reduced in age-related cortical atrophy.

42 Thus, cortical thinning may be rather associated with neuronal shrinkage or degeneration of synapses. While our cross-sectional study does not provide information about the causal relationship between cortical thickness and anxiety symptoms, we hypothesize that underlying pathological neurodegeneration may result in reduction of synapses in cortical circuits involving the insula. This in turn may be seen on MRI as cortical thinning and lead to anxiety symptoms. Alternatively, it is possible that an additional risk factor may synergistically interact with the cortical thinning pathway and lead to anxiety symptoms. It also seems plausible that a confounder such as age may lead to both cortical thinning and anxiety symptoms.

Our study should be interpreted in light of its strengths and limitations. An important strength is that participants were from a large, well-described population-based study, thereby reducing selection bias as would occur with a clinic-based setting. The comprehensive clinical evaluation and access to medical record information from the Rochester Epidemiology Project provided the opportunity to adjust for multiple possible confounders, including age, sex, education, antidepressant medication use, medical comorbidities, and cognition. In contrast to most previous studies, we also adjusted for depressive symptoms. The comorbidity between anxiety and depression is very high; therefore, we additionally adjusted for depressive symptoms. The observed association between anxiety and cortical thickness remained the same, indicating that the association is over and above what can be explained by comorbid depressive symptoms. Furthermore, the study sample allowed us to investigate associations of anxiety with imaging variables (i.e., cortical thickness and amygdalar and hippocampal volume) in more than 1,500 participants. Additionally, we examined associations between anxiety symptoms and cortical thickness as continuous variables, whereas most previous studies chose categorical classifications.

This study also has potential limitations. The BAI is a self-reported questionnaire and may therefore be subject to recall bias. However, the BAI is a well-validated and widely used scale.

24 Additionally, our study is limited by its cross-sectional design, which does not allow for interpretations of the direction of causality. Therefore, longitudinal studies are needed to replicate our findings. Furthermore, even though the Mayo Clinic Study of Aging extensively evaluates cognition and we were able to exclude participants with MCI or dementia from this study, we could not account for subjective cognitive impairment, which can also be accompanied by symptoms of anxiety.

Our findings indicate that a higher level of anxiety symptoms was associated with lower thickness in various cortical regions after adjusting for age, sex, education, medical comorbidity, antidepressant medication, and global cognition. This cross-sectional association is informative in that a dimensional approach has raised an important hypothesis that needs to be tested in a future longitudinal cohort study to investigate as to who will eventually develop further neurodegeneration leading to a phenotype of cognitive impairment. However, after additionally adjusting for depressive symptoms, the findings changed markedly, and only the association between anxiety symptoms and reduced insular thickness remained significant. Therefore, this finding may provide insight into the specific structural correlates of anxiety symptoms after adjusting for possible confounding effects of co-occurring depression.