Inclusion of performance validity tests (PVTs) and symptom validity tests (SVTs) has been described as “an essential part of a neuropsychological evaluation” (

1) and “important in all evaluations” (

2). From 1995 through 2014 there was a significant increase in neuropsychological research on validity assessment. During this decade, 25% of peer-reviewed papers in two major neuropsychology journals addressed this subject, highlighting the increased attention to and awareness of validity assessment issues (

3). Historically, “SVT” was used to represent validity of both self-reported symptoms and performance on cognitive or behavioral testing. More recently, “SVT” has evolved to represent self-report of mood, personality, symptoms, or behavior; in contrast, “PVT” reflects performance on objective tests of cognitive abilities, which is thought to be independent of but not mutually exclusive to “SVT” (

4). The importance of assessing validity in clinical and forensic contexts has been generally accepted, and a clinical/forensic evaluation that omits validity assessment may be considered substandard depending on context (

1,

5); however, the use of validity testing in research settings has received less attention.

Stand-alone PVTs are relatively easy tests, designed solely for identification of invalid performance, and are created using known groups paradigms or simulations studies. Some of the most popular tests include the Test of Memory Malingering (TOMM), the Word Memory Test (WMT), and the Medical Symptom Validity Test (MSVT) (

6). Additionally, numerous cognitive tests have scores that are sensitive to invalid performance, permitting the development of embedded validity indices (for a review, see Boone [

7]). Because these embedded PVTs are part of established measures of cognitive performance, genuinely impaired individuals can appear invalid (see Erdodi and Lichtenstein [

8]). This is less of a concern when using stand-alone PVTs, except in cases of severe cognitive impairment, because they are relatively easy and were developed to measure validity rather than cognitive functioning. Factors such as conditions involving known cognitive impairment, inattention, or distress are less well studied in stand-alone PVTs, and the studies that do exist suggest that even very impaired individuals pass these measures (

9).

A handful of studies have evaluated various factors that could contribute to failed PVTs. For example, Batt and colleagues (

10) conducted an experimental study in a sample of acquired brain injury patients who completed the TOMM and the WMT under one of three conditions: control, simulated malingering, and distraction. The distraction group completed an auditory span addition task during the learning stage of the PVTs. This resulted in significantly poorer performance compared with the control group for the WMT but not the TOMM, suggesting that the WMT may be sensitive to situational distractors. The simulated malingering group had the worst performance on both measures. Another study using an acute pain condition experimentally manipulated with an ice pressor task found that moderate pain did not affect PVT performance (

11). Other potential explanations have also been hypothesized, such as stereotype threat, negative expectation biases, or hindsight biases, but empirical evidence is lacking on these explanations (

12). These studies present possible reasons for PVT failure other than intentional response bias or poor effort.

Theoretically, psychiatric distress might impede performance on PVTs if symptom burden were severe. For example, in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), hypervigilance or active flashbacks could potentially disrupt attention and impair performance. However, few studies have examined PVT failure in groups with PTSD. Specifically, a 2011 review cited eight studies of PTSD and cognition in veterans (

13). Although a number of impairments were observed in different domains across those eight studies, none evaluated performance validity (

14–

21). When performance validity is accounted for, outcomes differ. For example, using a research sample of veterans meeting criteria for PTSD, Clark and colleagues (

22) found that poor performance on stand-alone and embedded PVTs accounted for 10%–28% of the variance in cognitive performance. In a study of veterans clinically referred for neuropsychological evaluations, 69% of veterans with PTSD failed the WMT (

23). Participants with PTSD who failed validity demonstrated cognitive impairment compared with healthy controls; there were no differences between participants with PTSD who passed validity and healthy controls.

More recent studies on cognition and PTSD that accounted for invalid performance have demonstrated variable results. For example, Stricker and colleagues (

24) evaluated cognitive functioning in female veterans with and without PTSD, after excluding invalid performance. The PTSD group showed significantly poorer scores on intelligence, verbal learning (but not retention), executive functioning, and processing speed; however, all scores were within the average range for both groups. Similarly, Wrocklage and colleagues (

25) found significantly poorer performance on measures of processing speed and executive functioning, but not memory. A longitudinal study (

26) found associations between PTSD symptom severity and measures of recall and reaction time after excluding invalid participants, though clinical significance is unclear from the data that were presented. In addition, the relation between PTSD severity and memory functioning was bidirectional, resurrecting questions initially raised by Gilbertson and colleagues (

17) regarding whether poorer memory serves as a risk factor for development of PTSD. A study by Verfaellie and colleagues (

27) found “small but measurable neuropsychological performance decrements” associated with PTSD (p. 340). Despite statistically significant findings of associations between PTSD and various cognitive variables, none of these studies give a clear indication of the clinical significance of any findings, and none controlled for symptom validity. Although PTSD is not classified as a primary cognitive disorder, additional evaluation of PVT failure in PTSD samples is warranted.

SVTs include stand-alone measures of self-report items, structured interviews, and validity scales embedded in larger multiscale self-report inventories. Scales are generated from various types of items, such as rarely endorsed symptoms in different populations, implausible symptom combinations, or inconsistent responding across a measure (for further details, see Rogers [

28]). Veterans with PTSD demonstrated higher rates of elevated scores on overreporting scales in several studies. For example, 50% of a sample of Vietnam veterans with PTSD had elevated MMPI F scores, compared with 8% of the non-PTSD group (

29). In a study of Iraq and Afghanistan veterans seeking PTSD treatment, 54% had elevated (over 80 T) MMPI-2 F scores (

30). One possible explanation is that elevated SVT scores reflect greater psychological distress. This theoretical phenomenon has been labeled a cry for help (

31). Initially used to describe a pattern of invalid report on the MMPI, the term has been broadened to other measures of symptom exaggeration, though this causal explanation has yet to be verified in research. Like PVT failure, a better understanding of SVT failure rates is necessary. If elevated clinical distress (a potential treatment target) results in failure on validity measures in those diagnosed with PTSD, it would alter the interpretative approach to those measures.

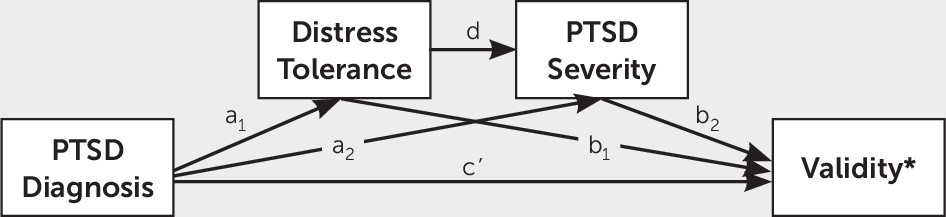

The purpose of the present study was to examine the association between a PTSD diagnosis and performance on both SVTs and PVTs in a research setting that precluded overt secondary or clinical gain. We hypothesized a serial mediation model wherein the association of PTSD diagnosis and performance on PVT or SVT would be mediated by distress tolerance and PTSD symptom severity, respectively.

Methods

Participants

Data analyzed in this project were drawn from a larger study reviewed and approved by the local institutional review board. Informed consent was collected before participation, and participants were made fully aware that procedures were for research purposes only. Study procedures were fully explained, and participants provided verbal and written consent before any study activities. Welfare and privacy of participants were protected and maintained. All participants were screened initially by telephone for eligibility. They were then scheduled for an in-person assessment visit during which final eligibility for an imaging visit was determined. The data for these analyses were obtained from the interview visit; therefore, it is possible that participants met some of the exclusion criteria listed below.

Inclusion criteria for the larger study were deployment in support of the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, English fluency, 18 years of age or older, ability to complete study tasks, and ability to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria were brain injury history outside of deployment involving loss of consciousness, moderate to severe traumatic brain injury (TBI), neurological disorder, severe mental illness (e.g., psychotic disorder, bipolar disorder), current substance use disorder (past 30 days), or current psychotic symptoms. Participants completed cognitive testing, interviews, and self-report questionnaires. Tests were administered in a fixed order by trained master’s- or doctoral-level study staff, with consultation and oversight by board-certified neuropsychologists.

Measures

Psychological.

The Clinician–Administered PTSD Scale-5 (CAPS-5) (

32) is a 30-item structured interview for the diagnosis of PTSD using the DSM-5. Items assess duration of symptom, level of distress, and effect on functioning and can be scored to reflect current functioning (past month) to provide a current diagnosis or worst functioning (worst month) to produce a lifetime diagnosis. Interviewers rate responses on a Likert-type scale (0=absent to 4=extreme/incapacitating). Participants meeting full DSM-5 criteria using the CAPS-5 at the time of the assessment were assigned a PTSD diagnosis. The PTSD Checklist-5 (

33) is a 20-item self-report questionnaire that assesses severity of symptoms occurring secondary to an identified trauma over the past month. Respondents use a Likert-type scale (0=not at all to 4=extremely); total score ranges from 0 to 80, with higher scores reflecting greater symptom severity. Continuous scores were used in analyses to reflect level of symptom severity. The Distress Tolerance Scale (

34) is a 15-item self-report questionnaire measuring ability to experience and tolerate negative affect. Respondents use a Likert-type scale (1=strongly agree to 5=strongly disagree); total scale score ranges from 15 to 75, with higher scores reflecting better tolerance.

Validity.

The MSVT (

35) is a stand-alone PVT that employs a forced-choice verbal recognition memory format. Participants scoring below cutoff scores published in the manual for the Immediate Recall, Delayed Recall, or Consistency subscales were classified as failing the test. The b Test (

36) is a stand-alone PVT using letter recognition and discrimination. The manual provides cutoff scores for different groups; the current study used the recommended cutoff for the Normal-Effort Groups Combined (sensitivity=73.6, specificity=85.1). Participants scoring above the cutoff were classified as failing. The Structured Inventory of Malingered Symptomatology (SIMS) (

37) is a stand-alone SVT that produces a Total Scale and the following subscales: Psychosis, Neurologic Impairment, Amnestic Disorders, Low Intelligence, and Affective Disorders. All subscales comprised 15 items scored true or false, for a total of 75 self-reported items. The Total Scale score ranges from 0 to 75, with higher scores indicating more items endorsed. Participants scoring above the manualized clinical cutoff score for the Total Scale were classified as failing. Post hoc analyses used continuous scores for SIMS subscales.

Data Analysis

All analyses were conducted in SAS Enterprise Guide 7.1 (SAS Institute, Cary, N.C.). Serial mediation analysis was conducted using the PROCESS macro 3.1 (

38). There were no missing data points. Hypothesis testing was conducted using three separate serial mediation analyses predicting b Test, MSVT, and SIMS failure (dichotomous, 1=failure). Post hoc tests analyzed continuous SIMS subscale outcome variables. The independent variable was PTSD diagnosis (dichotomous, 1=present); distress tolerance and symptom severity were serial mediators, respectively. All reported confidence intervals are 95%, bootstrapped with 10,000 subsamples. Results were considered significant if the p value was <0.05 and 0 was not included in the confidence intervals. False discovery rate (

39) was used to adjust for multiple comparisons at an alpha of 0.05.

Despite the focus of this article on PTSD and outcomes, TBI is also common in the veteran population. To assess for potential effects of TBI, we conducted analyses with mild TBI as a covariate. No veterans in this sample had a greater than mild TBI. There was no change in outcomes when accounting for TBI; therefore, analyses presented do not include a covariate.

Results

Demographic characteristics of the study participants are presented in

Table 1. Participants were 306 veterans (13.07% female) between 23 and 71 years old. Most participants identified racially as either white (57.52%, N=176) or black (39.54%, N=121). PTSD was diagnosed in 35.95% of the sample (N=110). Less than half of participants had a history of mild TBI (47.71%, N=146). There were no significant differences on age in veterans with and without PTSD (p=0.453), though veterans with PTSD (mean=14.63 [SD=1.81]) tended to have fewer years of education compared with those with no PTSD diagnosis (mean=15.29 [SD=14.96]), t=2.56, df=304, p=0.011.

Overall, 6.86% of participants failed the MSVT (N=21), 5.23% failed the b Test (N=16), and 42.81% failed the SIMS (N=131). The mean score on the Distress Tolerance Scale was 51.01 (SD=13.55; range, 15–75) and on the PTSD Checklist-5 was 32.09 (SD=19.78; range, 0–77). Direct effects are summarized in

Table 2. PTSD diagnosis was significantly associated with distress tolerance (p<0.001). Both PTSD diagnosis (p<0.001) and distress tolerance (p<0.001) were significantly associated with symptom severity.

Performance Validity

MSVT failure was positively associated with PTSD severity (

Table 2) but not PTSD diagnosis or distress tolerance. The overall model was significant (

Table 3). The indirect effect models that were significant included PTSD severity (

Table 4), indicating PTSD severity as a driving explanatory factor. Failure on the b Test was not significantly associated with PTSD diagnosis, distress tolerance, or symptom severity (

Table 2).

Symptom Validity

SIMS failure was positively associated with a diagnosis of PTSD, negatively associated with distress tolerance, and positively associated with symptom severity (

Table 2). The overall indirect effect of the serial mediation analysis of PTSD diagnosis on SIMS failure was significant such that presence of a PTSD diagnosis was associated with failure on the SIMS when distress tolerance was low and symptom severity was high (

Table 4).

Post hoc analyses were conducted to determine if subscales of the SIMS were differentially predicted by the serial mediation model. Overall, the serial mediation model significantly predicted all subscales (

Table 4). In comparison to the other subscales, the effect size for the Low Intelligence subscale was relatively small.

Discussion

PTSD severity was directly associated with failure on the memory-based PVT (MSVT), but not the PVT integrating visual attention and discrimination (b Test). Given that hypervigilance and poor concentration are symptoms of PTSD, these findings were unexpected. Results may reflect the generally higher sensitivity of the MSVT to validity threats, or they may reflect different patterns of performance across different types of tests. As noted by Boone (

40), it is atypical for a noncredible test-taker to underperform on every type of task administered. There may be an assumption that PTSD should be associated with memory impairment, and conscious or unconscious expectations about cognitive limitations associated with PTSD may have resulted in underperformance. There is mixed evidence regarding the association between PTSD and learning and memory. Results from studies excluding invalid participants have ranged from no significant decrements, to statistically but not clinically significant differences, to a complex bidirectional relation between PTSD and memory (

23–

26,

41,

42). Although significant steps were taken to minimize obvious secondary gain in the present study (e.g., participants were informed that research results would not be available for forensic or medical purposes, using a research-only sample), perception of potential gain may have remained. Participants with PTSD may receive monetary compensation for the condition through the Veteran’s Benefits Association; it is possible that they may have remained unconvinced that results could not affect compensation status.

Conversely, failure on the SVT was directly associated with a current PTSD diagnosis, self-reported poorer distress tolerance, and higher PTSD symptom severity. Specifically, individuals with PTSD who self-reported higher symptom severity and poor distress tolerance scored higher on subscales measuring atypical neurological problems, memory problems inconsistent with brain dysfunction, atypical mood/anxiety symptoms, general cognitive incapacity, and atypical psychotic symptoms. For veterans with PTSD, difficulty managing negative emotional states in general may contribute to symptom overreporting, perhaps reflecting inability to modulate emotional experiences or tolerate stronger affect. This is different from a cry for help, which insinuates that the purpose of endorsing high distress is an effort to communicate that distress is unbearable or to communicate a need for services. By definition, the cry for help phenomenon constitutes malingering because it involves conscious exaggeration as a means to an external incentive: namely mental health services. Our findings support an alternative explanation: a potential lack of distress tolerance or emotional control results in overreporting rather than an internal or external motivator (i.e., clinical attention or services). It is noteworthy that others have cautioned against using the psychopathology=superordinate line of logic (i.e., using psychiatric symptoms as a causal explanation for overreporting); approaching failed SVT interpretation using psychopathology as a causal explanation of very abnormal symptoms follows circular reasoning (

43). In line with Merten and Merckelbach (

43), it is unlikely that individuals with PTSD are actually experiencing a high number of very bizarre, atypical, or implausible symptoms; when they fail SVTs, we must continue to interpret their self-report more generally as simply invalid.

On the basis of our findings, recommendations would be to include both SVTs and PVTs in clinical evaluations and research. A current PTSD diagnosis and symptom self-report were related to PVT and SVT performance in our sample. Though this is consistent with existing clinical and forensic recommendations (

1), it is often overlooked in research contexts. In our study, 43% of a research-only sample failed an SVT (compared with 53% in a study of treatment-seeking veterans with PTSD [

44]), and failing was not directly related to a PTSD diagnosis. Additionally, clinicians and researchers should consider including PVTs that sample across multiple domains, not just memory or attention. In our sample, PTSD severity was associated with failing a memory PVT but not an attention-based PVT. Inclusion of only one of these measures would lead to very different conclusions about the validity of cognitive results. If a client or participant fails a PVT, clinicians should refrain from attributing that failure to a PTSD diagnosis or a cry for help. Regarding treatment, these results suggest that veterans with PTSD and difficulty tolerating negative affect (e.g., report higher distress and symptomatology) might benefit from an intervention to strengthen distress tolerance skills. It is perhaps unsurprising that, in a disorder marked by avoidance, poor distress tolerance was associated with worse self-reported symptoms. Increased coping skills may contribute to improved mental health and reduced overreporting of psychological and cognitive symptoms.

Limitations of the present study included low rates of failure on the b Test, which may have contributed to null findings for this PVT. Future studies replicating our preliminary findings of differences using PVTs based on diverse domains are warranted. We did not examine contributions of comorbid psychiatric diagnoses or conditions such as depression and TBI. Additional studies may seek to replicate the current findings in different psychological conditions, such as major depression and TBI, or investigate whether increasing comorbidity is related to increasing problems with distress tolerance or validity failure. We also did not assess interrater reliability for the CAPS-5. Finally, results may not generalize to other populations, such as older veterans, active-duty service members, and civilian samples.