Stroke is one of the most disabling neurological conditions, with functional changes bringing negative feelings and maladaptive behaviors, including high levels of anger. Anger includes a wide range of expression and intensity, from feeling angry to explicit aggressive behavior.

1,2 Anger has frequently been divided into the emotion itself and its cognitive and behavioral elements, hostility or irritability and aggression, respectively.

1–3 Spielberg et al.

4 distinguished between state and trait anger. State anger corresponds to a psychobiological emotional state of feeling angry, from irritability up to rage, and varies according to situational circumstances. Trait anger is a relatively permanent disposition that modulates the perception and the response with higher levels of state anger.

Anger is a frequent symptom after stroke.

5–9 Higher levels of anger can have a major impact on the treatment and recovery of stroke patients and the wellbeing of caregivers.

5,7,10–12 Factors associated with anger after stroke are still unsettled.

5 After stroke, anger is probably best explained by a multifactorial model including premorbid variables; factors linked to stroke as a brain disease; and psychological, environmental, and socioadaptive variables.

5,13The purpose of this study was to 1) identify the frequency of anger and its emotional, cognitive, and behavioral components in patients with acute stroke; 2) distinguish between state and trait anger and between expression and control of anger; 3) analyze the association between anger and demographic, clinical, and imaging variables, between anger and psychological and socioadaptive variables, and between anger functional disability at hospital discharge; and 4) compare the perceptions of patients and caregivers about anger.

Methods

Patients

Consecutive patients with acute stroke (≤7 days after stroke onset), who were hospitalized in a 12-bed stroke unit of a neurology service, were enrolled in the study from October 2009 to December 2011. Inclusion criteria were 1) diagnosis of ischemic stroke (IS) or intracerebral hemorrhage (ICH); 2) psychological assessment performed within 7 days after stroke onset; 3) a score ≥10 on the Glasgow Coma Scale on the items of “eye opening” and “best motor response” (avoiding the confounding effect of aphasia)

14; 4) a score <2 on the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale (NIHSS)

15 on the items of “best language” or “dysarthria” (absence of or a mild communication disturbance); and 5) no dementia or cognitive decline (defined as a diagnosis of cognitive impairment with effect on daily living activities) previous to the stroke and confirmed by a proxy.

Assessments

A trained psychologist (ACS) examined the patients with a standardized protocol. A neurologist (JMF) assessed the neurological status and reviewed the CT or MR imaging. Information about previous dementia or cognitive decline and psychiatric disorder was collected from medical records, caregivers, and medication review.

16To assess the frequency and profile of anger, we used the State-Trait Anger Expression Inventory-2 (STAXI-2)

4 according to the normative data for the Portuguese population.

17 The STAXI-2 was designed to assess the experience, expression, and control of anger; it has six scales and five subscales. One of the six scales, the Anger Expression Index (AX Index), has a total of 57 items measured on a 4-point scale. The State Anger (S-Ang) Scale measures the intensity of angry feelings and behaviors using three components: feeling (S-Ang/F), verbal expression (S-Ang/V), and physical expression (S-Ang/P). S-Ang was used as our primary dependent variable, since it measures the pattern and intensity of anger felt and expressed by patients after stroke. The Trait Anger (T-Ang) scale measures the frequency of angry feelings and behaviors over time, specifying temperament (T-Ang/T) and reaction (T-Ang/R). The other four scales—Anger Expression-Out (AX-O), Anger Expression-In (AX-I), Anger Control-Out (AC-O), and Anger Control-In (AC-I)—measure the expression and control of anger outside and inside. The results obtained in the Portuguese adaptation allowed us to consider only one scale for expression (AX) and one for control (AC).

17 The AX Index is a general index of the expression of anger. We also requested the primary caregiver for each patient to complete the STAXI-2.

Cognitive impairment was assessed with the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE).

18,19 Anxiety and depressive symptoms were assessed with the Hospital Anxiety Depression Scale (HADS),

20,21 according to DSM-IV-TR clinical criteria.

16 To assess the perception of the environment, we registered spontaneous complaints and asked the patients if there was something wrong, menacing, disturbing, or boring in the unit (complaints about the environment). Satisfaction with health care was assessed with the Satisfaction with Stroke-Care Questionnaire (SASC-19) Hospital subscale.

22Stroke type (IS and ICH) and location (brainstem or cerebellum, hemispherical, or both; left, right, or bilateral, brainstem or cerebellum or hemispherical; hemispherical deep or superficial; superficial anterior or posterior)

23 were defined based on clinical and imaging data. We classified IS as total anterior circulation infarcts, partial anterior circulation infarcts, posterior circulation infarcts, and lacunar infarcts based on clinical data and according to the Oxfordshire Community Stroke Project.

24 Functional disability at discharge was assessed with the modified Rankin Scale (mRS) (grade ≥3).

25The study was approved by the Ethical Committee of the university hospital (Faculdade de Medicina, Hospital de Santa Maria). Patients and caregivers provided informed consent.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using SPSS (version 22.0; SPSS, Chicago). A p value ≤0.05 was considered statistically significant. Chi-square with continuity correction and odds ratio with 95% confidence interval (95% CI) were used to test bivariate associations between anger (no anger or anger) and demographic variables (age, gender, and educational level); associated conditions (previous stroke, psychiatric disorder, hypertension, diabetes, alcohol abuse, and medical complications); clinical symptoms and signs (mild aphasia, mild dysarthria, neglect, hemiparesis); type, location of stroke, and IS subtype; cognitive impairment (higher or above the cut-point adjusted for education), anxiety and depressive symptoms (score >7 in each subscale), complaints about the environment; and mRS at discharge. We used the Mann-Whitney test (U) to compare medians of the continuous variables (NIHSS at admission and discharge, MMSE, HADS, and SASC-19) between the presence and absence of anger. For multivariable analysis of the predictors of anger in acute stroke, we performed a multilevel logistic regression, entering the variables with a p<0.10 on bivariate analysis in four blocks: variables prior to stroke, related to the stroke itself, hospital environment, and stroke consequences. We calculated the area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve to assess the predictive value of the model.

Results

Demography and Clinical Features

We studied a sample of 114 patients, 45% of whom were female, with a mean age of 62.1 years (SD=12.5, range 27–87 years) and an average of 6.3 years of education (SD=4.0, range 0–20 years). Patients were assessed at a mean of 4.6 days (SD=1.7, range 1–7 days) after stroke onset and were hospitalized on average 11.0 days (SD=9.6, range 2–67 days). Stroke severity at admission was assessed with NIHSS (mean=7.5 [SD=4.9], range 0–20). All the 114 patients had undergone a first acute CT scan, 60 (53%) received a second CT scan, and 75 (66%) underwent an MRI. Almost all the patients (94%) were very satisfied with health care received at the unit (mean=21.4, SD=3.6, range 4–24).

Table 1 presents the full description of the sample.

Profile of Anger in Acute Stroke

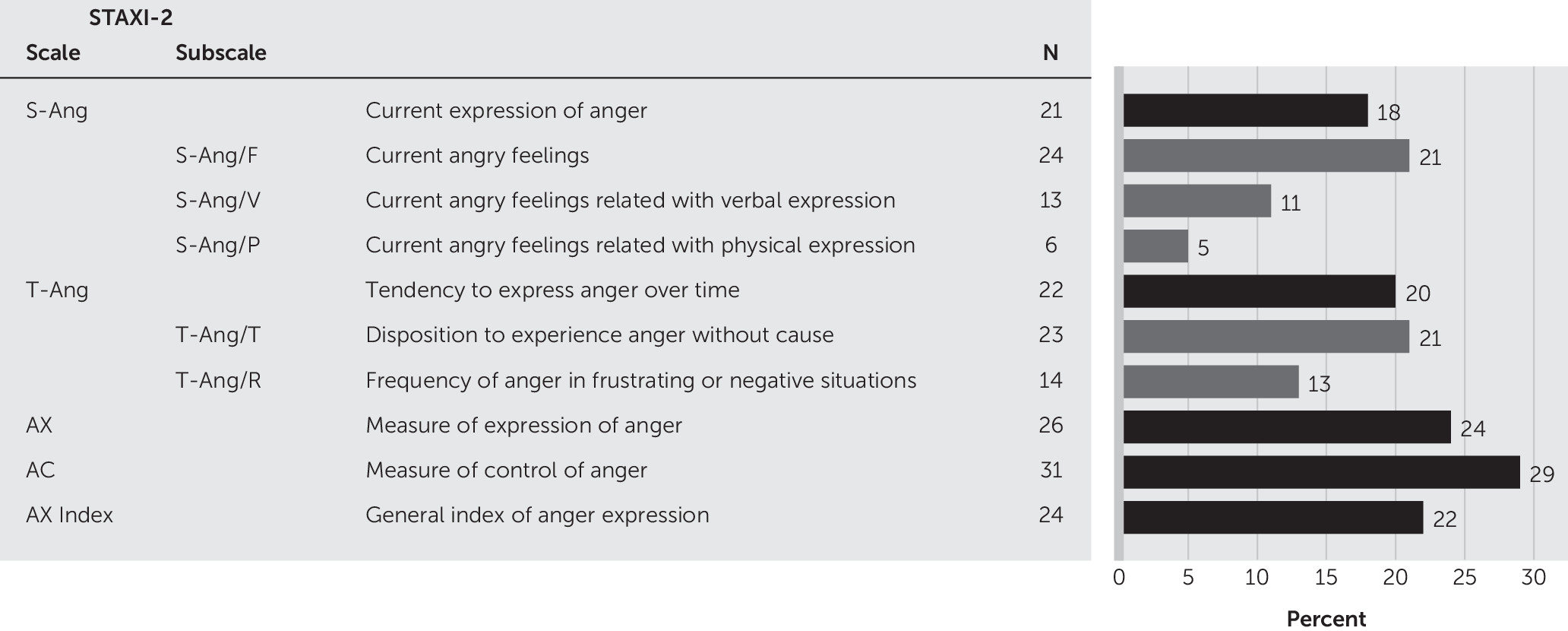

Twenty-one stroke patients (18%) were angry, independent of its expression (mean S-Ang=18.5 [SD=6.5], range 15–5; normative mean=17.47 [SD=3.97]). If we look for anger components, we found that 21% complained about feeling angry (mean S-Ang/F=7.2 [SD=3.3], range 5–20; normative mean=6.61 [SD=1.98]), 11% expressed anger verbally (mean S-Ang/V=5.8 [SD=2.2]), range 5–7; normative mean=5.58 [SD=1.55]), and 5% expressed anger physically (mean S-Ang/P=5.5 [SD=1.9], range 5–17; normative mean=5.27 [SD=1.81]).

Figure 1 presents the profile of anger in the sample.

Patients with anger were younger (U=446.50, p=0.00; χ

2=9.66, p=0.00); had more frequent hypertension (χ

2=4.87, p=0.03), cognitive deficit (χ

2=5.03, p=0.04), anxiety (U=301.50, p=0.00; χ

2=11.89, p=0.00), and depressive (U=606.50, p=0.02; χ

2=7.04, p=0.02) symptoms; had a longer stay at the hospital (U=604.50, p=0.01); and had more complaints about the environment (χ

2=14.75, p=0.00) and higher mRS scores (χ

2=5.01, p=0.04) (

Table 1).

Anger as a personality trait was present in 22 patients (20%) (mean T-Ang=17.9 [SD=6.4], range 10–40; normative mean=18.53 [SD=5.08]), meaning that those patients frequently felt and expressed anger. Twenty-three of the patients (21%) presented an angry temperament (mean T-Ang/T=6.7 [SD=3.0], range 4–16; normative mean=6.59 [SD=2.4]) and 14 (13%) an angry reaction (mean T-Ang/R=8.5 [SD=3.2], range 4–16; normative mean=9.25 [SD=2.94]).

Twenty-two percent of the patients had high values in AX Index (mean index=1.8 [SD=0.8], range 0.4–4.1; normative mean=1.81 [SD=0.78]), showing that those patients experienced intense angry feelings, independent of whether the feelings were expressed or suppressed. If we look for anger expression (mean AX=20.4 [SD=5.5], range 12–41; normative mean=18.75 [SD=4.57]), we found that 24% of the patients had high scores. In the anger control scale (mean AC=54.3 [SD=10.3], range 27–71; normative mean=49.51 [SD=12.15]) that assesses attempts to suppress anger, 29% of the patients controlled the expression of anger. This could mean that those patients suffered from chronic anger and had difficulty dealing with it.

We found a significant relationship between state anger and some of the other scales. Higher scores in S-Ang were associated with higher scores in T-Ang (U=568.00, p=0.01), T-Ang/T (U=612.00, p=0.01), T-Ang/R (U=622.00, p=0.02), AX (U=474.00, p=0.00), and AX-Index (U=566.50, p=0.00).

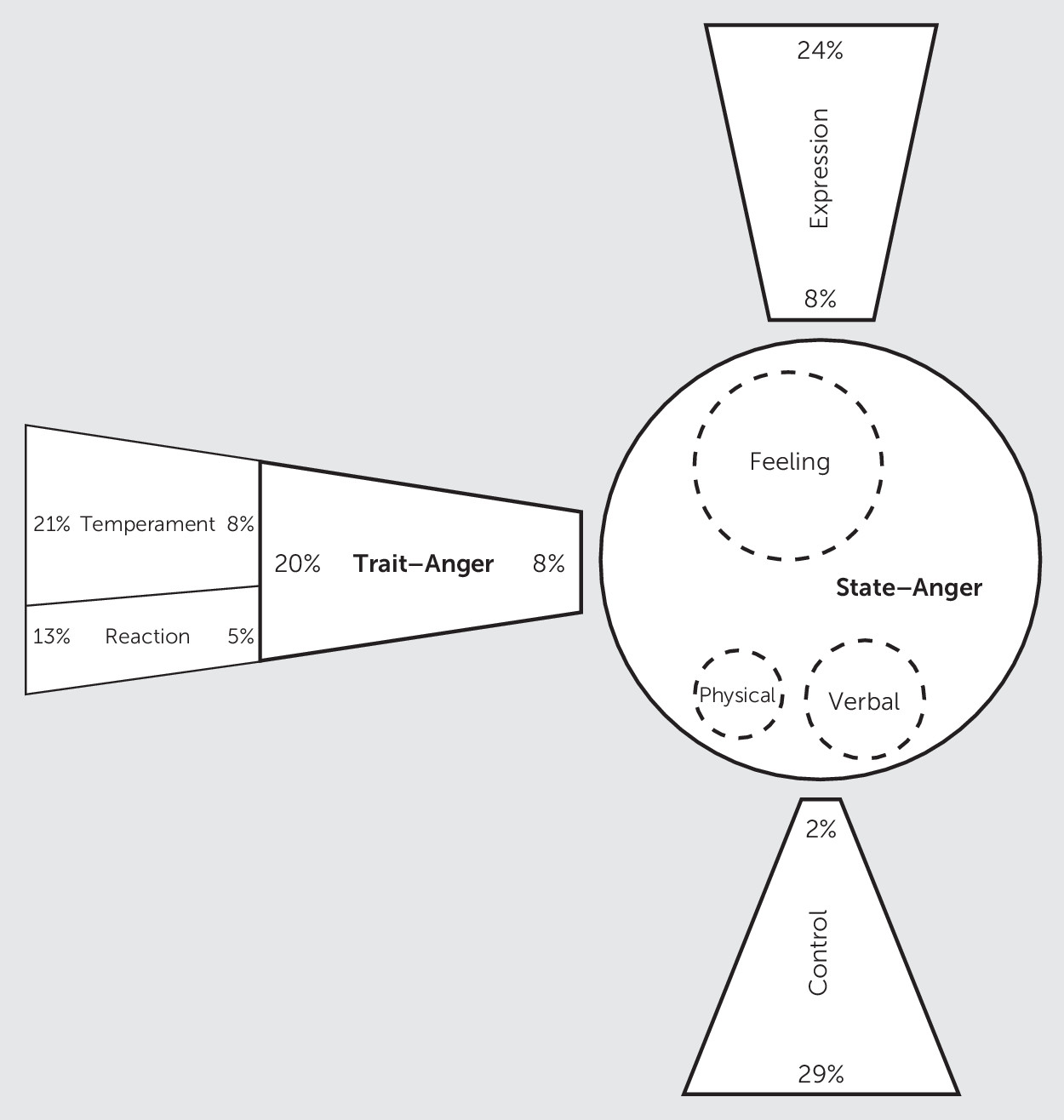

Figure 2 presents the relationship between state anger and the other scales or subscales.

We performed a stepwise multilevel logistic regression by introducing the variables prior to stroke (age, hypertension, and T-Ang) first, then those that are related to stroke (stroke type) second, the situational variables (complaints about the environment, satisfaction with care) third, and finally the variables related to stroke consequences (MMSE, HADS, and mRS). The best model revealed that age (odds ratio=7.2; 95% CI 1.31–39.47), HTA (odds ratio=4.44; 95% CI=1.08–18.32), complaints about environment (odds ratio=6.91; 95% CI=1.70–28.16), anxiety symptoms (odds ratio=5.40; 95% CI=1.12–23.79), and disability (odds ratio=7.97; 95% CI=1.76–36.08) were independent predictive factors for anger (R2=54%). The specificity of this model was 95%, sensitivity was 63%, positive predictive value was 75%, and negative predictive value was 92%. The area under the ROC curve was 90%.

The Perception of Caregivers About the Anger of Patients

We included 76 caregivers of the 114 stroke patients (67%), with a mean age of 54.3 years (SD=15.2, range 18–82 years) and an average of 7.7 years of education (SD=4.5, range 0–21 years). Seventy-one percent of the caregivers were female, 65% were spouses, and 29% were descendants. Seventeen caregivers (22%) evaluated the presence of significant anger in their relatives, while 12 (16%) assessed their stroke relative as having trait anger.

Caregivers rated higher levels of anger, both in general (S-Angcaregivers=19.5 versus S-Angpatients=17.4, Z=−2.8, p=0.01) and anger feelings (S-Angcaregivers=8.2 versus S-Angpatients=6.6, Z=−3.1, p=0.00), than patients. The 38 patients for whom there was no caregiver available had a higher frequency of anger (χ2=4.20, p=0.04).

Discussion

In this study, 18% of patients with acute stroke showed anger as a current state, and 20% showed anger as a personality trait. Our model, which explained 54% of the variance, revealed that angry patients were younger, had hypertension and anxiety symptoms more frequently, complained about the environment, and had more disability. We did not find any significant association between anger and type, location, or severity of stroke. We can summarize the profile of anger in our patients as follows: 1) more patients experienced intense angry feelings, and fewer expressed anger verbally or behaviorally; 2) a significant proportion said that they felt and expressed anger frequently (trait anger) in response to a wide range of stimuli (temperament); and 3) they had a tendency to control versus express their anger, avoiding its open expression.

As in other studies, we found interesting differences between subjective anger expression and anger as perceived by others.

9,13 Caregivers rated higher levels of state anger but similar levels of trait anger. Previously, we found that 41% of 180 patients with acute stroke showed denial, which limited their awareness of symptoms.

8 Anger is a negative symptom that patients may deny, undervalue, or not be fully aware of.

The literature about anger is marked by differences in the proper concept and time of assessment, which could explain the major differences in its prevalence.

7,9,13,26,27 Ramos-Perdigués et al.

5 recently summarized the evidence of anger in stroke independently of whether anger was the main outcome. The authors indicated methodological problems for the scarcity of studies and the difficulties in comparing them: lack of consistency in terminology, different times of assessment, use of global psychiatric measures, exclusion of patients with aphasia and cognitive deficits, and difficulty controlling potentially relevant variables. They included 18 studies with prevalence between 12% and 57% and conflicting results related to variables associated with anger. Of the five studies conducted in the acute phase, only one used a standardized scale to measure trait anger. Our present study is innovative because for the first time a specific scale to assess anger and its different dimensions was used in the acute phase of stroke.

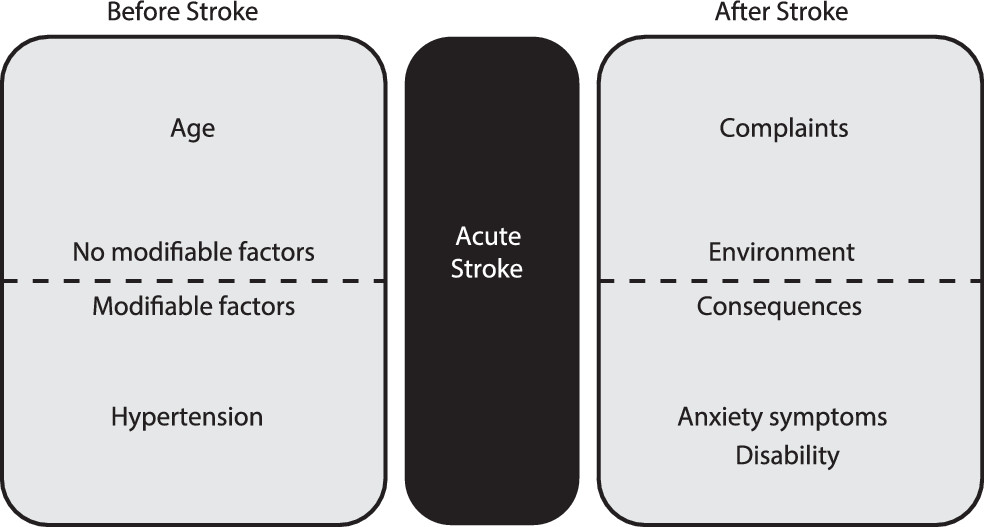

In a previous study, we suggested that anger in acute stroke can emerge due to the contribution of four factors: 1) brain lesion, 2) stroke as a nonnormative event, 3) anger as a personality trait, and 4) hospital environment.

13 We are now able to improve the model by grouping predictive variables as they are present before, during, and after stroke (

Figure 3). First, prestroke variables include age, the profile of anger based on past experiences and trait anger, and hypertension. Second, stroke itself is a sudden and potentially disabling condition. Finally, after stroke, there are its psychological and functional consequences and the influence of the environment. In fact, patients have to cope with and accept the acuteness and unexpectedness of stroke and its symptoms and simultaneously deal with new requirements and expectations. Sudden hospitalization can be a threat stimulus if the patients perceived something wrong, menacing, disturbing, or boring in the stroke unit. The patients could react with fear, symptoms of depression or anxiety, denial, catastrophic reaction, and also anger.

8,28,29 The role of a psychosocial dimension in the emergence of anger was highlighted in our previous study, which showed a similar frequency of anger between patients with acute stroke and coronary artery disease.

13 In fact, both are acute, sudden, and life-threatening conditions requiring hospitalization, with a similar potential to trigger anger. The major difference is the presence of brain injury in stroke, which we believe is a relevant factor, but the lack of systematic imaging data from diffusion and FLAIR-MR sequences precluded a detailed analysis of the localization of lesions.

The strengths of our study are the use of a well-studied anger scale that allowed us to describe not only state anger after stroke but also a premorbid trait as a tendency to express anger. We could also distinguish between different ways of expressing and controlling anger. We collected information of different dimensions about the patient, disease, and environment, which helped us to better understand the emergence of or the increase in the tendency to express anger. A major limitation of our study is the possibility of selection bias, resulting from the relatively young age of the sample, limiting its external validity. Our study is cross-sectional, while emotions, cognitions, and behaviors are variable over time and could be influenced by different factors and temporarily contextualized situations.

In summary, anger in acute stroke seems to be a complex symptom of a disturbance of emotional control, related to the severity and the physical and psychological consequences of stroke. Anger should be screened for and characterized during the acute phase because its early detection, combined with the comprehension of the personal, clinical, and environment context, may prevent its negative impact on care and rehabilitation.