The concept of moral injury has recently emerged in the research literature as a separate aspect of trauma exposure, distinct from posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (

15). Moral injury is not classified as a mental disorder. It is a dimensional problem that can have profound effects on critical domains of emotional, psychological, behavioral, social, and spiritual functioning (

15–

18).

The definitions of moral injury have evolved considerably since its introduction in the 1990s, although a consensus definition has not yet emerged (

11,

16,

18–

22). The original definition, which was based on work with Vietnam era veterans, focused on failures by leaders. This type of moral injury required that three circumstances be present: “a betrayal of what’s right, by someone who holds legitimate authority, in a high-stakes situation” (

20). A later definition of moral injury, which was based on work with Iraq and Afghanistan era veterans, focused on moral failures by the individual (

16). This type of moral injury requires that the individual has experienced a potentially injurious event by “perpetrating, failing to prevent, bearing witness to, or learning about acts that transgress deeply held moral beliefs and expectations” and the moral/ethical violation resulted in “lasting psychological, biological, spiritual, behavioral, and social impact” (

16). As this definition makes clear, it is important to separate experiencing a potentially morally injurious event from developing moral injury. This is similar to PTSD. Experiencing a trauma (criterion A) does not inevitably lead to developing PTSD. Whether a moral injury develops is determined by how the individual interprets the potentially injurious event. The appraisal process determines whether the event generates significant dissonance with the individual’s belief system and worldview (

11,

16,

22–

25).

As noted above, the concept of moral injury was initially developed and studied in the context of combat (

3,

11,

15,

24–

28). There is growing recognition that many of these situations also put civilians (e.g., residents/refugees, journalists, military family members) at risk for moral injury (

11,

29–

31). In addition, occupations other than military (e.g., first responders, police, health care providers) can include equivalent exposures (

11,

29,

30,

32–

34). Although much less studied, there are other types of events that are potentially morally injurious (e.g., military/civilian sexual trauma, betrayal by trusted others, homicide/suicide of a loved one, hearing/reading about traumatic events) (

29,

30,

35).

The core indications for development of moral injury include self-blame, trust issues, and spiritual/existential issues (

11,

21,

36–

39). Due to the broad range of possible morally injurious events, many researchers have separated events based on individual responsibility (e.g., perpetration, failing to prevent harm) or other responsibility (e.g., witnessing disproportionate violence, betrayal by trusted others) to better understand the pathological effects of each type (

28,

35,

40–

42). In general, events involving individual responsibility are more likely to lead to negative internally directed (self-referential) emotions and cognitions (e.g., guilt, shame, lack of self-forgiveness), whereas events involving other responsibility are more likely to lead to negative externally-directed emotions and cognitions (e.g., anger, trust issues, lack of other-forgiveness). Both types of events are associated with spiritual/existential issues (e.g., loss of faith, questioning morality). Until resolved, these internal conflicts can in turn exacerbate social problems (e.g., isolation, aggression, legal issues) and mental health symptoms (e.g., anxiety, depression, PTSD, substance abuse, suicide risk) (

43–

48).

Moral injury often co-occurs with PTSD, which has been conceptualized as a fear-based disorder. However, studies in military personnel and veterans have found that a significant minority of index traumas for PTSD are events that do not primarily evoke fear/threat (

3,

49). A few studies have begun to explore the possibility that the underlying neurobiology of PTSD may be affected by the nature of the index trauma (

50–

52). A meta-analysis (activation likelihood estimation) of functional MRI (fMRI) studies reported both similarities and differences when studies were grouped by PTSD index trauma type (combat-related, sexual/physical abuse, natural disasters) (

1). It is noteworthy that although areas of greater activation were predominately in the right hemisphere for both the combat-related and sexual/physical abuse PTSD groups, there was little or no overlap (

Figure 1). One study has compared resting-state regional cerebral metabolic rate between veterans grouped by PTSD index trauma type (danger- and/or fear-based, nondanger-based) as well as to both trauma and civilian controls (

2). Regions of interest (ROIs) were brain areas previously reported to be activated by fear stimuli (bilateral amygdala, right rostral anterior cingulate cortex) or by traumatic script imagery (right dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, left posterior cingulate cortex, left precuneus). Veterans with PTSD as a result of danger- and/or fear-based traumas (i.e., life threat to self or other) had higher metabolism in the amygdalae (

Figure 1). In contrast, veterans with PTSD due to nondanger-based traumas (i.e., witnessing violence, traumatic loss, moral injury by self or other) had higher metabolism in the precuneus (

Figure 1). As noted by the authors, heightened metabolism in the precuneus for nondanger-based traumas may relate to its role in self-referential processing (

2).

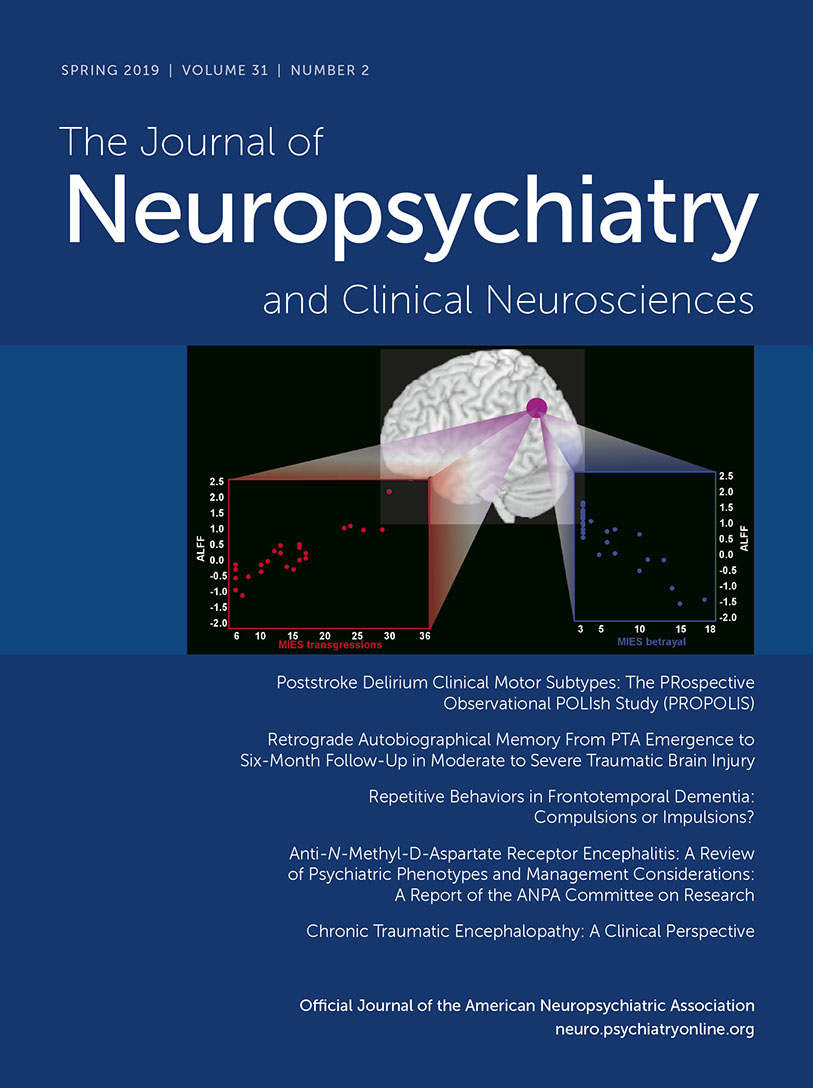

Studies of index events for combat-related PTSD have reported that 25–34% resulted in moral injuries (

3,

49). Moral injuries differed from index traumas related to life threat as they were more strongly associated with emotions that developed after the event rather than emotions experienced during the event (

3). An fMRI study of military veterans has explored relationships between resting-state activity (amplitude of low frequency fluctuation) and symptoms of PTSD (Clinician Administered PTSD Scale [CAPS]) and moral injury (Moral Injury Events Scale [MIES]) (

4). Total symptom scores on the CAPS and MIES were not significantly correlated with average amplitude of low frequency fluctuation in any ROI (bilateral amygdale, medial prefrontal cortex, dorsal anterior cingulate cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, inferior parietal lobule). Both subscales of the MIES (transgressions, betrayals) correlated with inferior parietal lobule ROI activity (

Figure 1), but in opposite directions (Cover). This was also found in the whole-brain voxel-based analyses. MIES-transgressions was also positively correlated with amplitude of low frequency fluctuation in the fusiform gyrus and posterior insula. In contrast, MIES-betrayals was positively correlated with amplitude of low frequency fluctuation in the precuneus. As discussed by the authors, these results indicate that the neural correlates of PTSD and moral injury differ at least in part (

4).

The best treatment for moral injury remains unclear, as most research has focused on alleviating PTSD symptoms. Clinical studies indicate that evidence-based treatments for PTSD (prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy) provide some reductions in symptoms (e.g., guilt, shame) arising from coexisting moral injury (

10,

11). As noted in both reviews, the focus on identifying trauma-related beliefs and cognitions that are at least partially inaccurate (e.g., exaggerated, distorted, erroneous) as targets for interventions is the likely mechanism. Consistent with this interpretation, a study in veterans reported that the ability to make meaning of a possible trauma by reconciling the discrepancies between one’s belief system and situational appraisal of the event appears to be vital in decreasing the risk for mental health symptoms (

43). Similarly, a study of cognitive processing therapy for PTSD due to military sexual trauma reported that reductions in self-blame (but not negative cognitions about self or world) preceded and predicted reductions in PTSD symptoms (

53). A recent set of case examples supports efficacy of prolonged exposure therapy and cognitive processing therapy for treating PTSD due to moral injury, provided the index trauma is correctly identified (

54).

Others have modified existing treatments to better address the combination of PTSD and moral injury (

55–

58). A group treating traumatized refugees combined loving kindness mediation with cognitive processing therapy to promote development of positive emotional states (

56). A group treating veterans incorporated a spiritual component into cognitive processing therapy to address aspects of moral healing (e.g., spiritual struggles, repentance, forgiveness) (

57,

58). Both approaches look promising based on the example cases provided. Adaptive disclosure, which was developed for treating active duty military, combines techniques from cognitive processing therapy with relatively brief exposure therapy (emotion-focused imaginal exposure coupled with meaning making and cognitive restructuring) to address events involving life-threat, traumatic loss or moral injury (

55). A randomized clinical trial of adaptive disclosure combined with loving kindness mediation is presently being conducted in veterans (

59). Pilot studies also support the usefulness of mindfulness-based therapies (i.e., mindfulness-based stress reduction, loving kindness mediation, mantram repetition) as adjuncts to usual care in veterans and civilians with PTSD (

56,

60–

64). Beneficial effects included increasing positive emotions, self-acceptance, emotional flexibility, and emotional regulation skills.

Several treatment approaches designed specifically to promote healing from moral injury have been developed, and preliminary studies suggest value (

11,

65). One challenge is recognition that in some cases the patient’s beliefs and judgements about their experiences are factually correct (

9,

10,

66). Thus, acknowledgment of the past moral/ethical violations (i.e., opening up) may be essential to begin the healing process (

9–

11). A small study of veterans in a residential PTSD treatment program supports the potential of addressing moral injury in a group setting using acceptance and commitment therapy (

67). A pilot study of a cognitive-behavioral therapy module addressing the moral and spiritual impacts of killing reported both acceptability and positive treatment effects (

68). It is noteworthy that all veterans had previously completed prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Self-forgiveness and making amends are key intervention targets to restore spiritual well-being (

9,

68). This is also the goal of Building Spiritual Strength, a group intervention for PTSD designed to be facilitated by either mental health providers or chaplains experienced in mental health counseling (

69). Historically, chaplains have been major providers of care for military experience-related problems, including moral injury (

70). Pastoral narrative disclosure is an intervention-based on a confessional model, developed specifically for use by chaplains (

71). The focus of pastoral narrative disclosure is to have individuals reflect on the morally injurious experience, consider the guilt and shame, seek forgiveness, and reconnect with themselves and others. Direct participation from chaplains, clergy, and religious communities in the treatment process provides insight and support to help address the spiritual issues that arise from moral injury (

18,

21). The value of incorporating chaplains into health care has been emphasized by both Departments of Defense and Veterans Health Administration (

22,

72,

73).

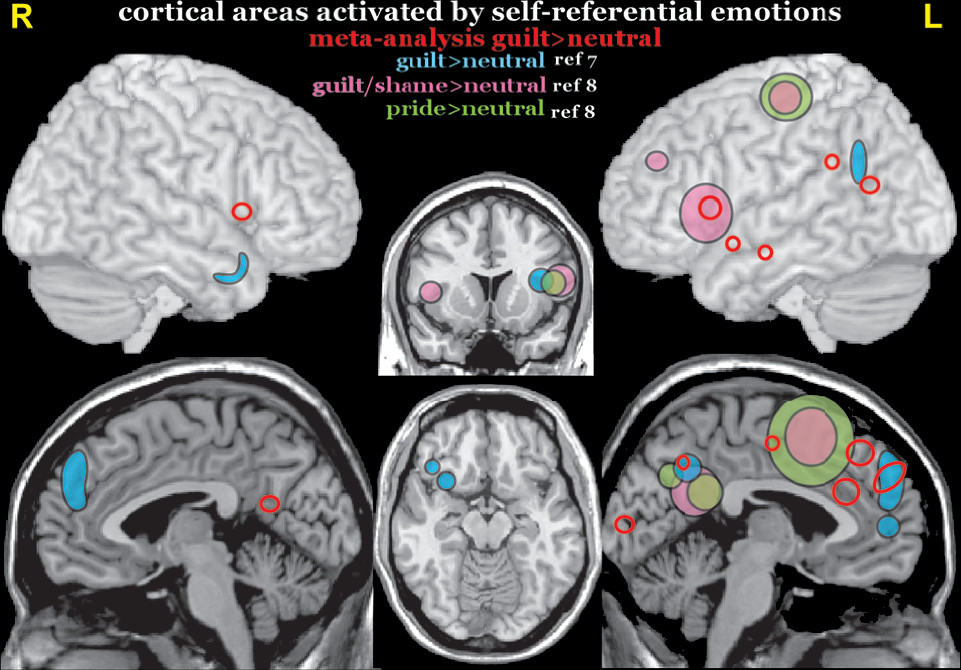

As noted above, negative self-referential emotions such as guilt and shame are core symptoms of moral injury. Functional imaging studies in healthy individuals have begun to identify the areas activated by different self-referential emotions (

5,

6). A systematic review summarized the neural correlates of guilt, embarrassment, and shame (

5). Guilt was more likely associated with activity in the ventral anterior cingulate cortex, posterior temporal regions and the precuneus. Embarrassment was more likely to be associated with activity in the ventrolateral prefrontal cortex and amygdala. Shame was more likely to be associated with activity in the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, posterior cingulate cortex, and sensorimotor cortex. Although guilt- and shame-activated distinct areas of the brain, there were also shared networks that involve emotional processing, self-referential processing, and social cognition (

5). Although methodological approaches to guilt induction varied considerably, a recent meta-analysis of the neural correlates of guilt identified multiple areas, primarily in the left hemisphere (

Figure 2) (

6). Most relevant to understanding the neural correlates of emotional changes associated with development of moral injury (e.g., guilt, shame) are studies that utilized autobiographical scenarios to induce reexperiencing an emotional state (

7,

8). Both studies reported activations in left precuneus/retrosplenial cortex and left inferior frontal gyrus/anterior insular cortex associated with negative (compared with neutral) self-referential scenarios (guilt, shame) (

Figure 2) These areas were also activated by positive self-referential scenarios (pride) (

7).

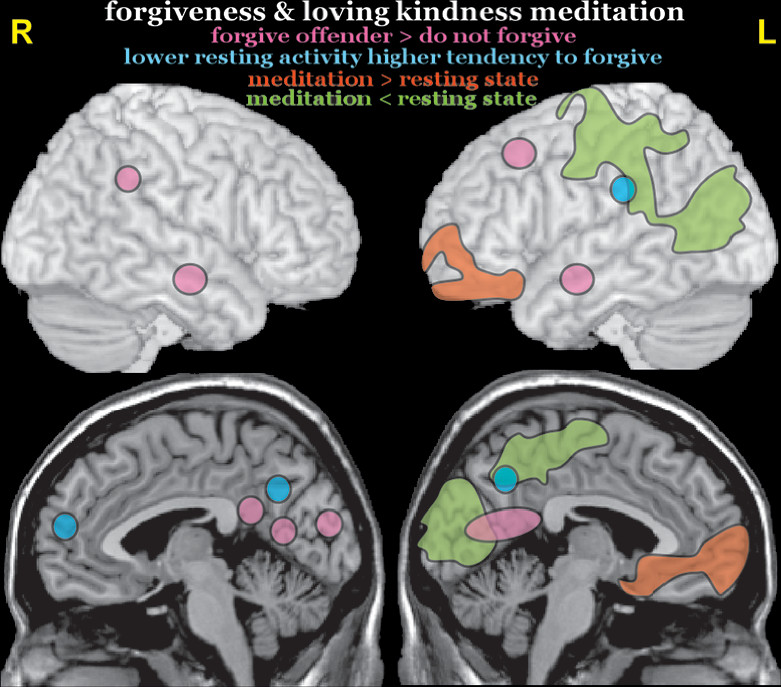

Although interventions designed to facilitate healing from moral injury are still in the early stages of development and testing, learning to forgive moral/ethical transgressions by self and others is a common theme (

9–

11). Studies have not yet addressed the neurobiology of forgiving serious transgressions by self or known others (

74). Two studies of healthy individuals have identified neural correlates related to forgiving others for transgressions (

Figure 3). A task-activated fMRI study reported higher activity in multiple areas (left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex, right inferior parietal lobule, bilateral middle temporal gyrus, posterior cingulate cortex, and occipital cortex) when participants were instructed to forgive compared with when they were instructed to not forgive offenders (

12). A resting-state fMRI study reported that spontaneous activity (amplitude of low frequency fluctuation) in regions associated with mentalizing and self-referential processing (right dorsomedial prefrontal cortex, bilateral precuneus, left inferior parietal lobule) was negatively correlated with scores on the tendency to forgive scale (i.e., higher resting-state activity was associated with lower tendency to forgive transgressions by others) (

13). In the absence of functional imaging studies on self-forgiveness, the neural correlates of loving kindness meditation may be informative. An fMRI study of experienced meditators reported that loving kindness meditation (compared with resting-state) resulted in both increases (left medial and anterior prefrontal cortices) and decreases (left parieto-occipital cortex) in activity (

14). It is noteworthy that the areas of decreased activity partially overlap with areas in which lower resting-state activity correlated with higher forgiveness (

13,

14).

In summary, although the research is early stage, there is growing evidence that the neurobiology underlying PTSD may differ by index trauma type. Moral injury, while often coexistent with PTSD, is not fear-based. Elucidating the neural correlates of moral injury, while extremely difficult in laboratory settings, would be valuable in guiding development of successful therapies. Challenges include the need to induce strong, predictable, and reproducible emotional states, incorporation of individually specific factors such as spiritual background, culture, community, and the nature of the trauma.