When the pioneering neurosurgeon Wilder Penfield moved from New York to Montreal in 1928, he arrived with a passion to “find a way of understanding what the brain did and

how it did it” (

2, p. 133). To this end, Penfield envisioned a multidisciplinary team that would work in a neurological institute where patient care and research had equal priority.

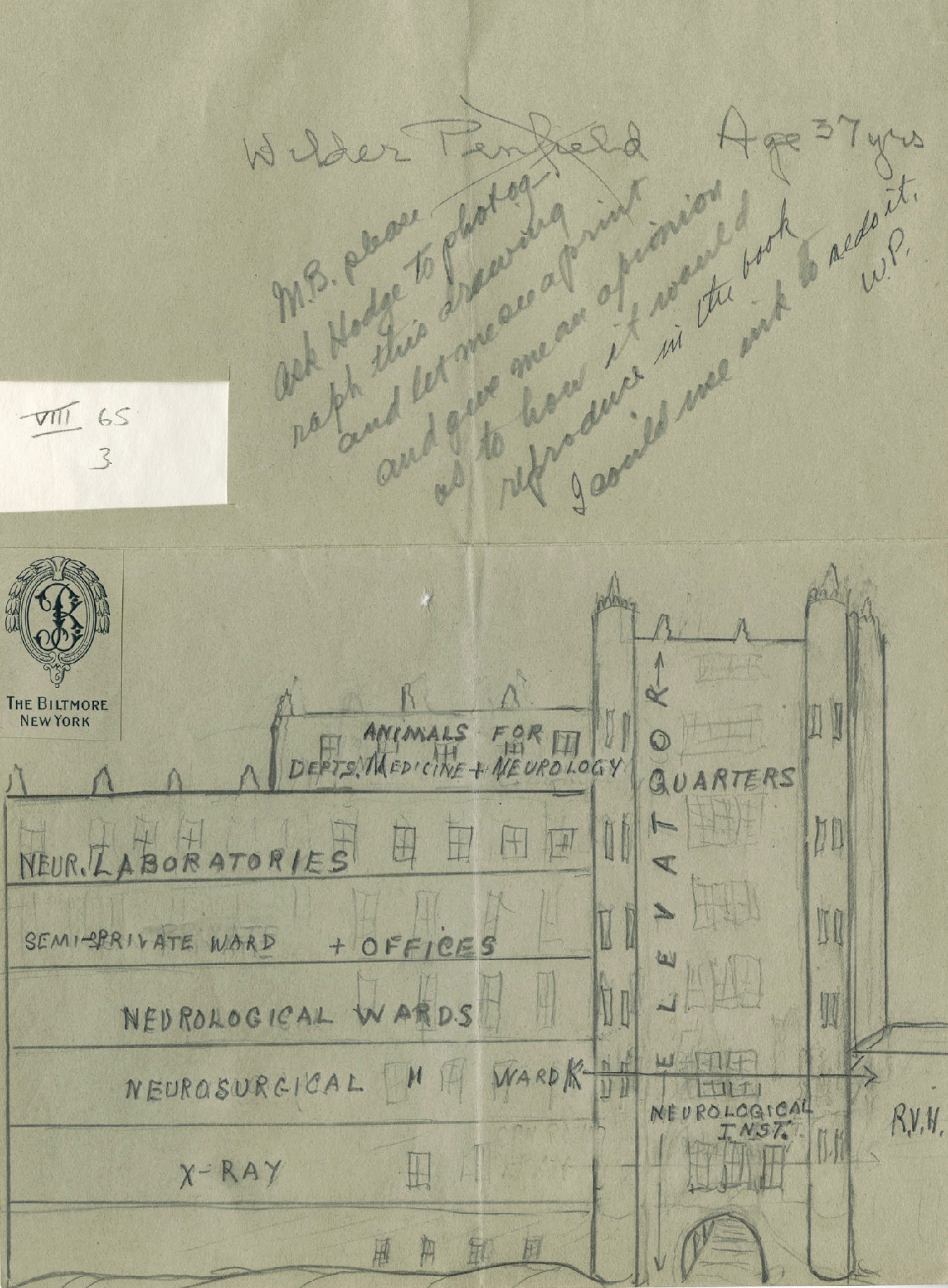

In 1929, Penfield outlined his plan in a letter to Edward William Archibald, Department of Surgery Chair at RVH, enclosing a sketch on hotel stationery (

Figure 1). This paradigmatic, “back of the envelope” drawing captured what Penfield had in mind. Penfield’s future institute would connect with RVH—an embodiment of facilitated collaboration between clinicians and basic science researchers.

Many factors influenced Penfield’s vision. After beginning to write a book on the fundamental principles of neuropathology, he had realized that “far too often…someone else, somewhere in the world…could write a better chapter” (

2, p. 129). Seeing the value of a selected team, he shifted his role from sole author to editor.

Penfield also valued research with clinical applications, having observed that breakthroughs in basic science research were unpredictable, while the needs of patients were ever-present. Indeed, Penfield’s letter to Archibald (

3) was written only 6 weeks after Penfield had operated on his own sister’s brain tumor: “The resentment I felt because of my inability to save my sister spurred me on to make my first bid for an endowed neurological institute” (

2, p. 221).

Although psychiatry was not a core discipline at the inaugural institute, Penfield always envisioned a role for psychiatry. In original discussions with Rockefeller Foundation physician-philanthropist Alan Gregg, Penfield noted, “[N]eurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry eventually should be joined together somehow in thought and plan, in the laboratory for scientific study, and in teaching” (

2, p. 296).

Penfield’s vision came to fruition in 1934 as the MNI, funded by the Rockefeller Foundation and private donors. Penfield was involved in planning virtually every detail of the building, including innovations to facilitate the mission; for example, buzzers in operating rooms could call fellows from their laboratories once a patient’s brain had been exposed (

4, p. 149). The MNI’s first annual report cited 939 patients cared for and an output of 39 scientific publications (

5).

As fundamental as the architecture was, Penfield asserted that the enterprise of scientific discovery was the crucial factor in binding a team together: “It is not the building…It is something beyond all that, something that may be compared to the spirit of a group of explorers” (

6, p. 6). Penfield led his expeditionary team to investigate what he called “the most promising unexplored body of knowledge in the whole field of medicine” (

2, p. 296).

Since Penfield’s time, “architecture” that supports collaboration has expanded with the development of the Internet. Multidisciplinary teams now frequently number in the hundreds, span the globe, and include not only specialists from medicine, surgery, and psychology but also neuroscientists, data scientists, physicists, biomedical engineers, and geneticists.