While neuropsychiatric symptoms have been well-recognized complications of Alzheimer’s disease in advanced stages of dementia, there is increasing interest in the characterization of these symptoms in early stages, such as mild cognitive impairment (

1,

2). Neuropsychiatric symptoms in mild cognitive impairment not only add to the distress of cognitive deficits but also may delineate subgroups of patients who are at higher risk for conversion to dementia (

3). Numerous studies have shown that in mild cognitive impairment, the predominant neuropsychiatric symptoms can include depression, anxiety, and apathy (

1,

4). Psychotic symptoms (delusions and hallucinations) typically manifest in the dementia stages (

2), with studies suggesting a direct correlation between the severity of the dementia and emergence of psychotic symptoms (

4). Indeed, the incidence rate of psychotic symptoms in mild cognitive impairment is fairly low, estimated to be between 3% and 14% (

5). Similarly, prevalence rates range between 1% and 10% (

6). The most common psychotic symptoms observed are persecutory delusions, delusional misidentifications, and visual hallucinations, although prominent psychosis early in the disease course may in fact be more suggestive of incipient Lewy body disease rather than Alzheimer’s disease (

7).

Koro delusion, which is not explicitly described in DSM-5 but was included in DSM-IV, has been previously defined as having a “sudden and intense anxiety that the penis will recede into the body and possibly cause death” (

8). Phenomenologically, this syndrome was previously described as a culture-bound syndrome, geographically localized to Southeast Asia, Japan, and China, although in the past few decades, the syndrome has been reframed to include both a culture-bound epidemic form and a nonculturally bound isolated form (

9). The isolated form has been described in numerous case reports around the world and generally understood to manifest in the context of broader underlying psychiatric pathologies, including body dysmorphic disorders, anxiety and panic disorders, somatoform disorders, dissociative and depersonalization disorders, and psychotic depression or, in the psychoanalytic arena, as a form of castration anxiety (

10–

13).

There have been few reports of Koro occurring in settings of nonpurely psychiatric conditions, that is, following some form of a direct physiologic insult, such as after a stroke (

14), in the setting of alcoholic hepatitis (

15), after abrupt withdrawal of an antipsychotic medication (

16), in the setting of a tumor of the corpus callosum (

17), in bronchial carcinoma with metastatic spread to the CNS (

18), and in the setting of abnormal epileptic activity (

19). For cases with direct CNS involvement, localization studies are limited but highlight the right temporoparietal lobes (

14), the genu of the corpus callosum (

17), the left frontotemporal lobe (

18), and the bitemporoparietal region (

19). Importantly, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports of this delusion in the setting of age-related neurodegenerative disease. Here, we present the first reported case of Koro syndrome presenting in mild cognitive impairment as a result of Alzheimer’s disease.

Case Report

A 78-year-old man was initially evaluated after being referred by his primary care physician for memory loss spanning more than 1 year. His medical history was notable for a minor stroke many years prior (which resulted in vision loss that was resolved). His evaluation at the memory disorders clinic revealed mild errors in recall, as well as deficits in visuoconstruction, and his score on the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) was 27/30. This corresponded to a Z score of –0.869 (based on sex, age, and 12 years of education) (

20). There were no signs or symptoms of parkinsonism. The patient reported independence in all of his activities of daily living as well as instrumental activities of daily living, which was corroborated by interview with a family member at a later date, and he was living alone. From this initial evaluation, he did not meet criteria for mild cognitive impairment (

21), but an initial workup was recommended. Reversible dementia studies revealed normal B

12 and thyroid-stimulating hormone levels. A brain MRI was ordered but not initially completed. A follow-up clinical evaluation 5 months later revealed mostly stable findings. Three months later, at a routine visit with his primary care physician, the patient complained that he “heard his penis shrink” and that it had “retracted.” This was causing him a great deal of anxiety. Physical examination of the penis revealed no abnormalities. The patient also reported deleting an e-mail that he had written to his primary care physician after hearing a voice emanating from a computer screen, associated with an incessant “banging” noise. Word-finding difficulty was also noted. The patient was once again evaluated at the memory disorders clinic, where he was seen urgently and reiterated that his penis had physically shrunk, despite knowledge of a normal clinical examination, although he was less anxious about the situation. He was apologetic about “bothering” his primary care physician and showed the neurologist letters of apology that he had written to his physician. There was some delusional content surrounding these letters, because he reported that the letters were “speaking” to him. A neurologic examination at this visit to the memory disorders clinic revealed mild deficits in registration, recall, and attention and concentration, but the patient’s visuospatial construction had improved. Now at age 79, his MMSE score was 24/30, which corresponded to a Z score of –3.274 (

20). He remained functionally independent, which was corroborated by family members, and thus he met criteria for mild cognitive impairment (

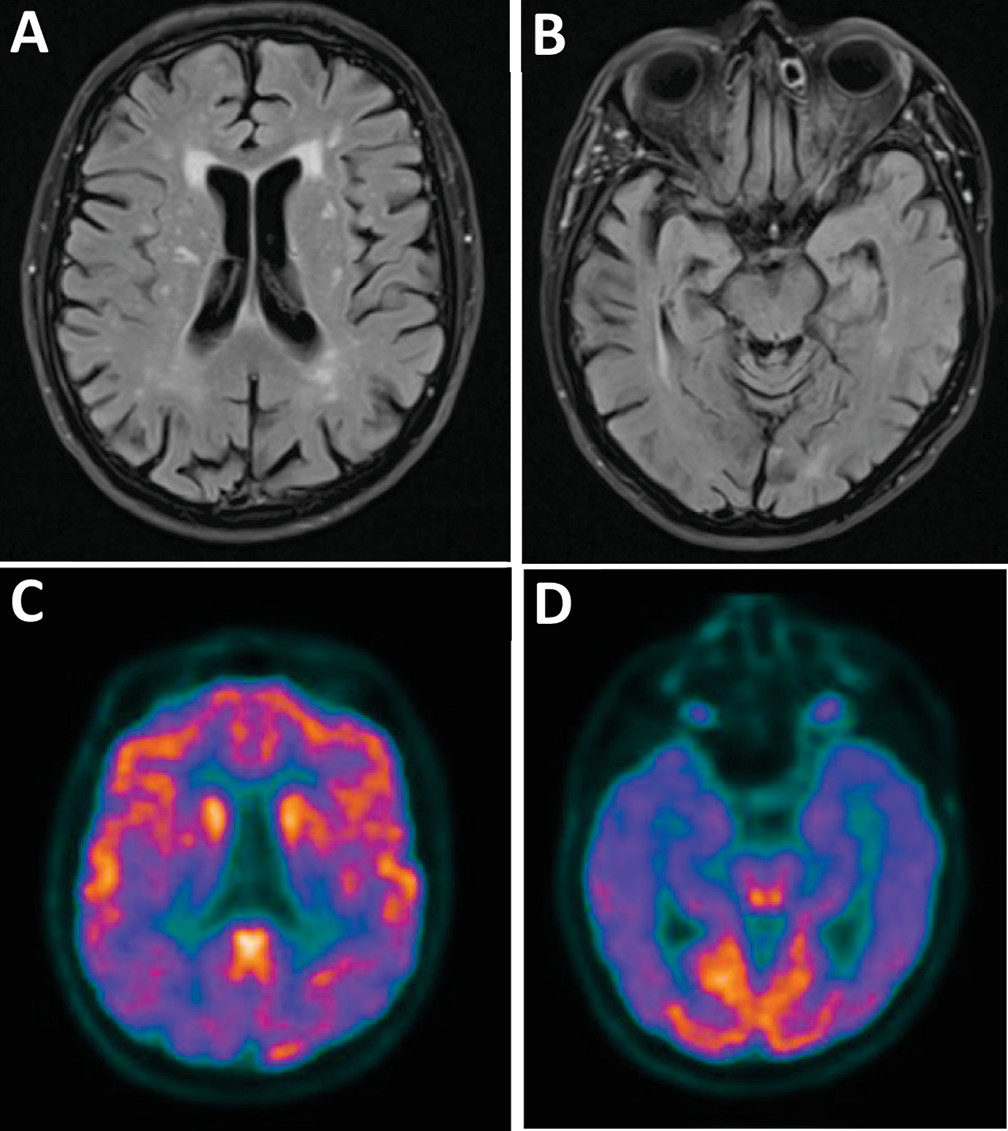

21). Brain MRI was completed and revealed mild supratentorial white matter changes suggestive of microvascular disease and mild bitemporal volume loss suggestive of Alzheimer’s disease (

Figure 1A and B). Fluorodeoxyglucose positron emission tomography (FDG-PET) showed decreased uptake in bilateral parietal and temporal lobes, consistent with Alzheimer’s disease (

Figure 1C and D).

Discussion

The above case is, to our knowledge, the first reported case of Koro syndrome manifesting in a patient with mild cognitive impairment as a result of Alzheimer’s disease. The rarity of this presentation is multifactorial. Patients with mild cognitive impairment have a decreased frequency and severity of neuropsychiatric symptoms as part of their symptom complex compared with patients with major cognitive disorder or dementia (

22). Of the neuropsychiatric symptoms that do manifest in mild cognitive impairment, psychotic symptoms are less frequently observed compared with the more common symptoms of apathy, irritability, depression, and anxiety (

1,

4,

6), and of the psychotic manifestations that are observed in patients with mild cognitive impairment, Koro syndrome is uncommon.

When considering the typical psychotic presentations among patients with mild cognitive impairment or Alzheimer’s disease, delusions of misidentification or persecution (which, it can be argued, are deeply interrelated) are the most commonly seen (

23). Delusional misidentification has been typically localized to the right hemisphere, especially the right frontal lobes (

24). Delusions of body image, under which Koro syndrome has been previously categorized, have also been attributed to right-hemisphere pathology, given the right hemisphere’s “role in the construction of the corporeal and psychological self” (

25). Gurin and Blum (

26) extensively described the relationship of the right hemisphere and delusion formation, essentially assigning four fundamental roles employed by the right hemisphere that afford an individual the “ability to create and maintain accurate appraisals of mental objects holistically and in context—be they simple visuospatial figures, complex narratives, or the self,” the loss of any one of which allows for the eventual formation of delusional content. While no clear area of localization has previously been attributed to the development of Koro syndrome, the few reported cases involving organic CNS lesions appear to suggest temporal lobe involvement, as delineated in the above case.

Why our patient developed this particular delusional syndrome is unclear. His FDG-PET revealed bitemporal hypometabolism, although this is a common finding in patients with Alzheimer’s disease at the mild cognitive impairment stage, most of whom do not have Koro delusion. Psychosis is more apparent in early stages of Lewy body dementia, although our patient’s FDG-PET did not show the occipital involvement that is often associated with this neurodegenerative condition. Furthermore, our patient did not present with other symptoms, such as parkinsonism, fluctuation, or dysautonomia. Delusions can be prominent early in frontotemporal dementia associated with the C9ORF72 mutation, which is thought to localize to frontal disease that was not apparent in our patient (

27). Although isolated Koro has been classically conceptualized as a form of body dysmorphic disorder or depersonalization, perhaps it can be viewed in the context of delusional misidentification, though in this setting it is a misidentification of the self. Such a framework would make Koro delusion in a patient with Alzheimer’s disease with mild cognitive impairment more understandable, if not at least less unusual. Similarly, the associated symptoms of anxiety and panic in this syndrome can be interpreted as a manifestation of underlying paranoid obsession with the loss of the self or, alternatively, with one’s inevitable demise.

Beyond etiopathology or nosology, from a clinical standpoint, it is evident from this case that, as previously suggested by Anderson (

14), Koro delusion itself should be understood as a symptom of a likely larger underlying insult, in our patient occurring as part of the symptom complex of mild cognitive impairment in Alzheimer’s disease. And, as demonstrated in the above case, regardless of the nosology and etiopathology of Koro delusion, the detection of underlying neuropsychiatric symptoms in patients with mild cognitive impairment, including the less common manifestation of delusions and hallucinations, plays an important prognostic role, given the greater risk of progression to dementia (

1).

Acknowledgments

The authors have confirmed that details of the case have been disguised to protect patient privacy.