Principal Findings

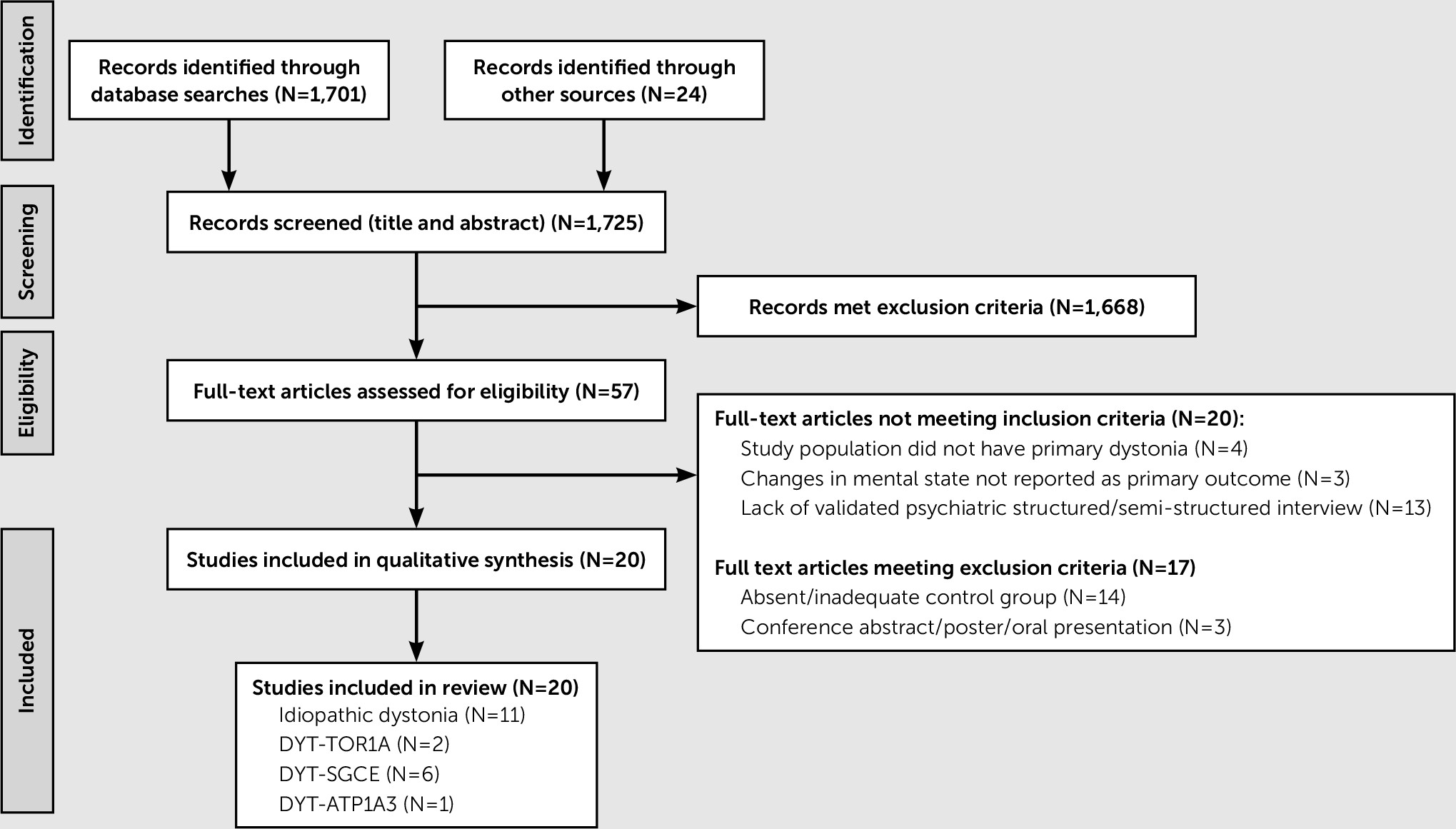

Simple pooling of available data suggests that for those subjects with idiopathic forms of dystonia, risk of psychiatric comorbidity is increased by a factor of seven compared with healthy control subjects (odds ratio=6.74, 95% confidence interval [CI]=5.32–8.52) and a factor of three when compared with control subjects with a medical comorbidity (odds ratio=2.95, 95% CI=1.99–4.37) (

Figure 2).

MMCs of the DYT-SGCE mutation are also more likely to experience psychiatric comorbidity than both NCs (odds ratio=5.88, 95% CI=3.97–8.69) and NMCs (odds ratio=8.37, 95% CI=3.77–18.57), suggesting that this association may be independent of gene status (

Figure 2).

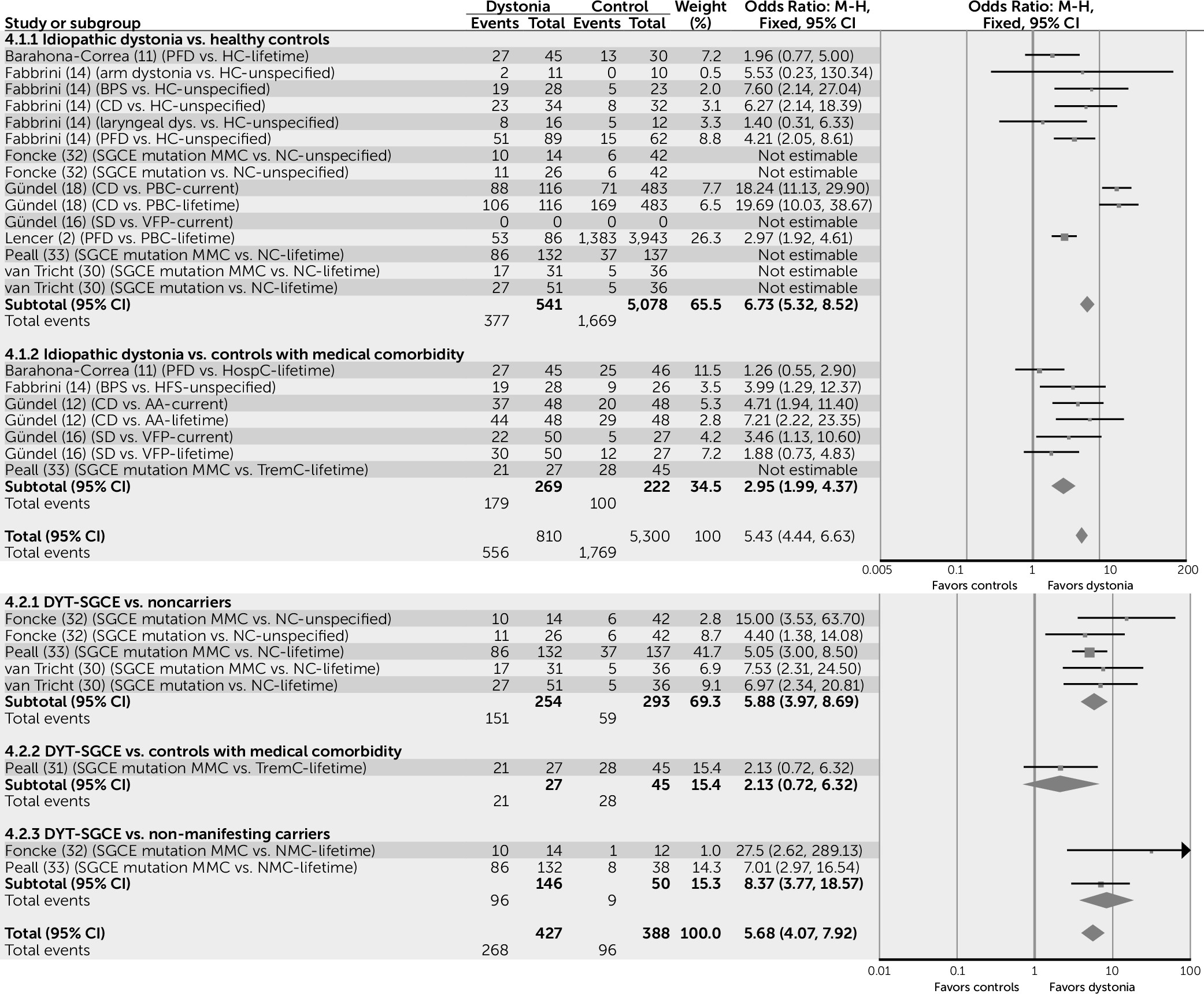

Associations are similar for mood disorders: Subjects with idiopathic forms of dystonia appear to have five times the risk of developing a mood disorder when compared with healthy control subjects (odds ratio=4.86, 95% CI=3.52–6.72) and two times the risk when compared with control subjects with a medical comorbidity (odds ratio=1.93, 95% CI=1.17–3.19) (

Figure 3). Subjects with idiopathic dystonia appear to be more likely to have major depressive disorder than healthy control subjects (odds ratio=4.79, 95% CI=3.64–6.29), though this association is not found when idiopathic dystonia is compared with control subjects with a medical comorbidity (odds ratio=1.19, 95% CI=0.80–1.77), suggesting that in idiopathic dystonia, major depressive disorder may develop as a secondary nonspecific response to illness.

In contrast to idiopathic dystonia, subjects with DYT-TOR1A appear to have a similar risk to control subjects (NC and NMC) of developing a mood disorder (odds ratio=1.19, 95% CI=0.79–1.80). Specifically, findings in the DYT-TOR1A population for major depressive disorder suggest that the risk is only marginally increased when MMCs are compared with NCs (odds ratio=1.85, 95% CI=1.08–3.17), but that this association is not found when MMCs are compared with NMCs (odds ratio=0.94, 95% CI=0.46–1.93). Overall, subjects with DYT-SGCE are more likely to have major depressive disorder when compared with both NCs (odds ratio=2.92, 95% CI=1.74–4.90) and NMCs (odds ratio=2.51, 95% CI=1.02–6.20), though not when compared with tremor control subjects (odds ratio=1, 95% CI=0.38–2.61).

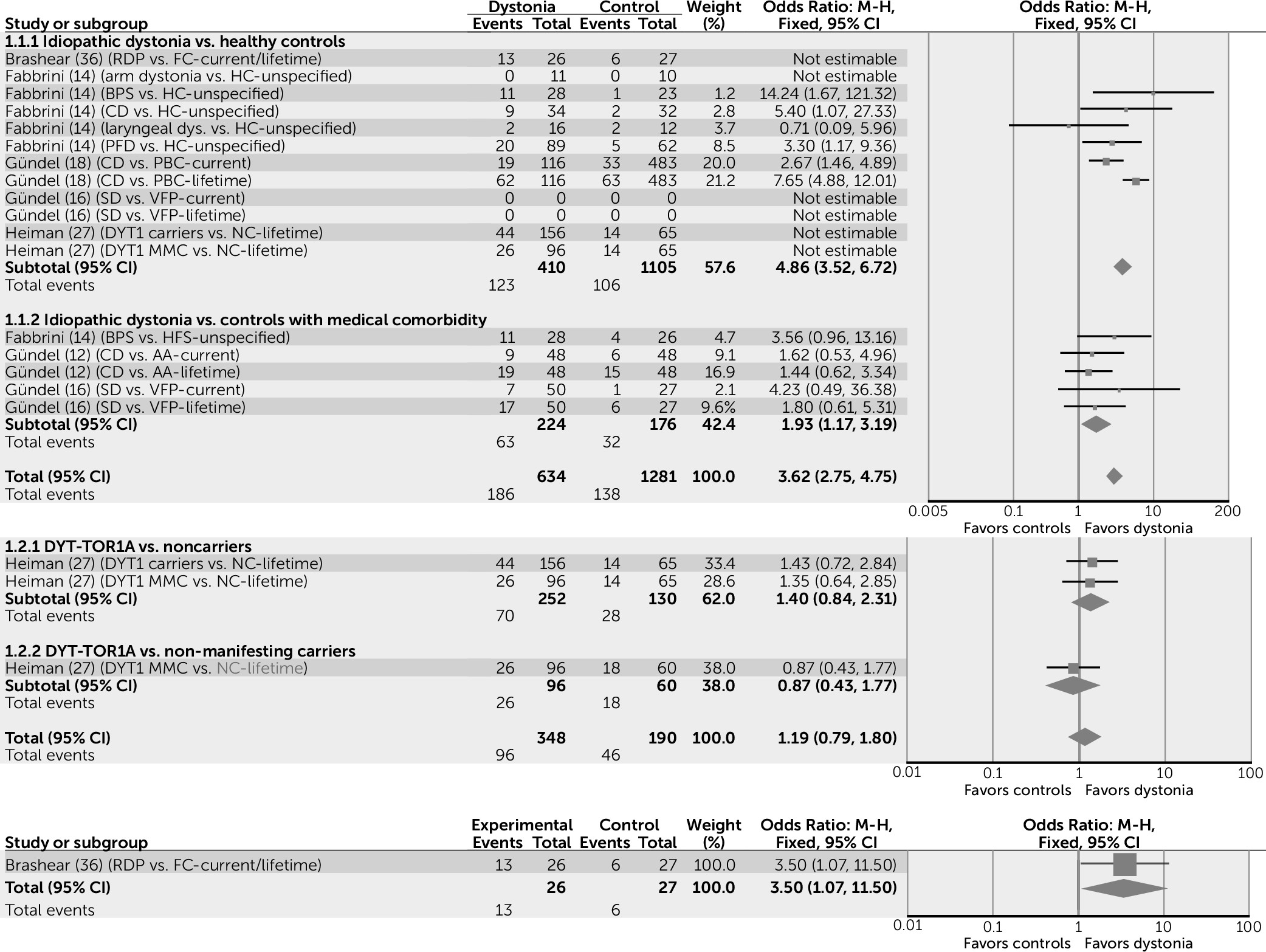

Anxiety conditions also appear to be increased in subjects with idiopathic dystonia, compared with both healthy control subjects and control groups with a medical comorbidity (odds ratio=5.77, 95% CI=4.63–7.19) (

Figure 4). The reasons for this observation are unknown; it may be that there is something specific to the experience of having an idiopathic form of dystonia that increases the risk of anxiety conditions in a way that other physical illnesses do not. The complex and ambiguous association between the human experience of neurotic symptoms and changes in muscle tone is well documented (

33). This effect may be bidirectional, with the perceived increase in muscle tone experienced in dystonia compounding the subjective experience of mental tension and leading to the subsequent development of anxiety. Specifically, the risk of OCD appears to be higher when subjects are compared with healthy control subjects (odds ratio=3.46, 95% CI=1.49–8.00), but not when compared with control subjects with a medical comorbidity (odds ratio=2.14, 95% CI=0.78–5.85).

Data are lacking for the association between overall anxiety conditions and inherited forms of dystonia. However, with regard to OCD, subjects with DYT-SGCE appear to be at higher risk than all forms of control (NC, medical comorbidity and NMC; odds ratio=6.47, 95% CI=4.09–10.25). Although this suggests that the presence of motor signs rather than the SGCE gene is important in the development of OCD, this observation should be treated with caution, as it is based on only four out of a possible 131 NMC subjects who reported a diagnosis of OCD. No differences were noted in the prevalence of OCD in subjects with both DYT-TOR1A and DYT-ATP1A3, when compared with control populations.

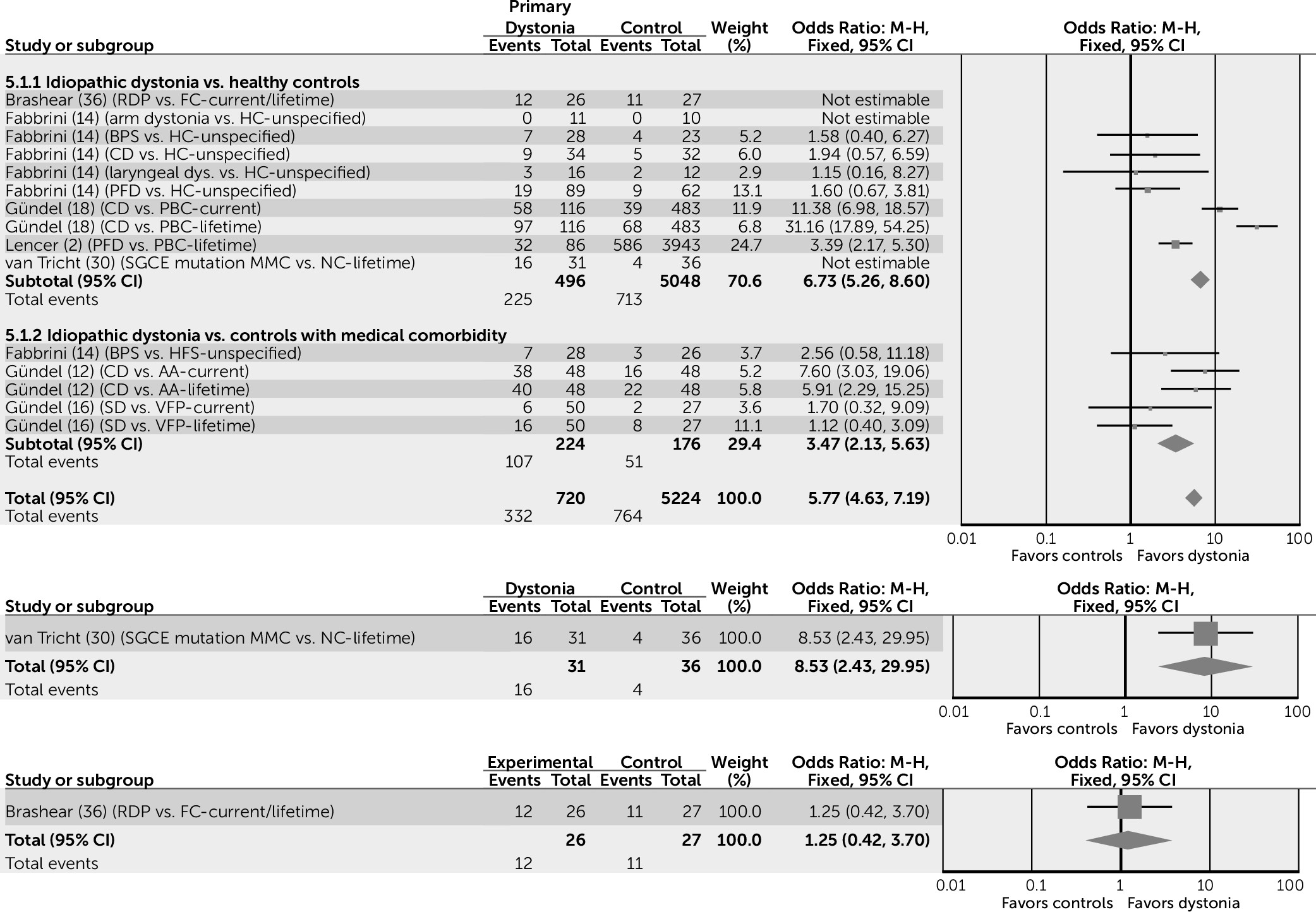

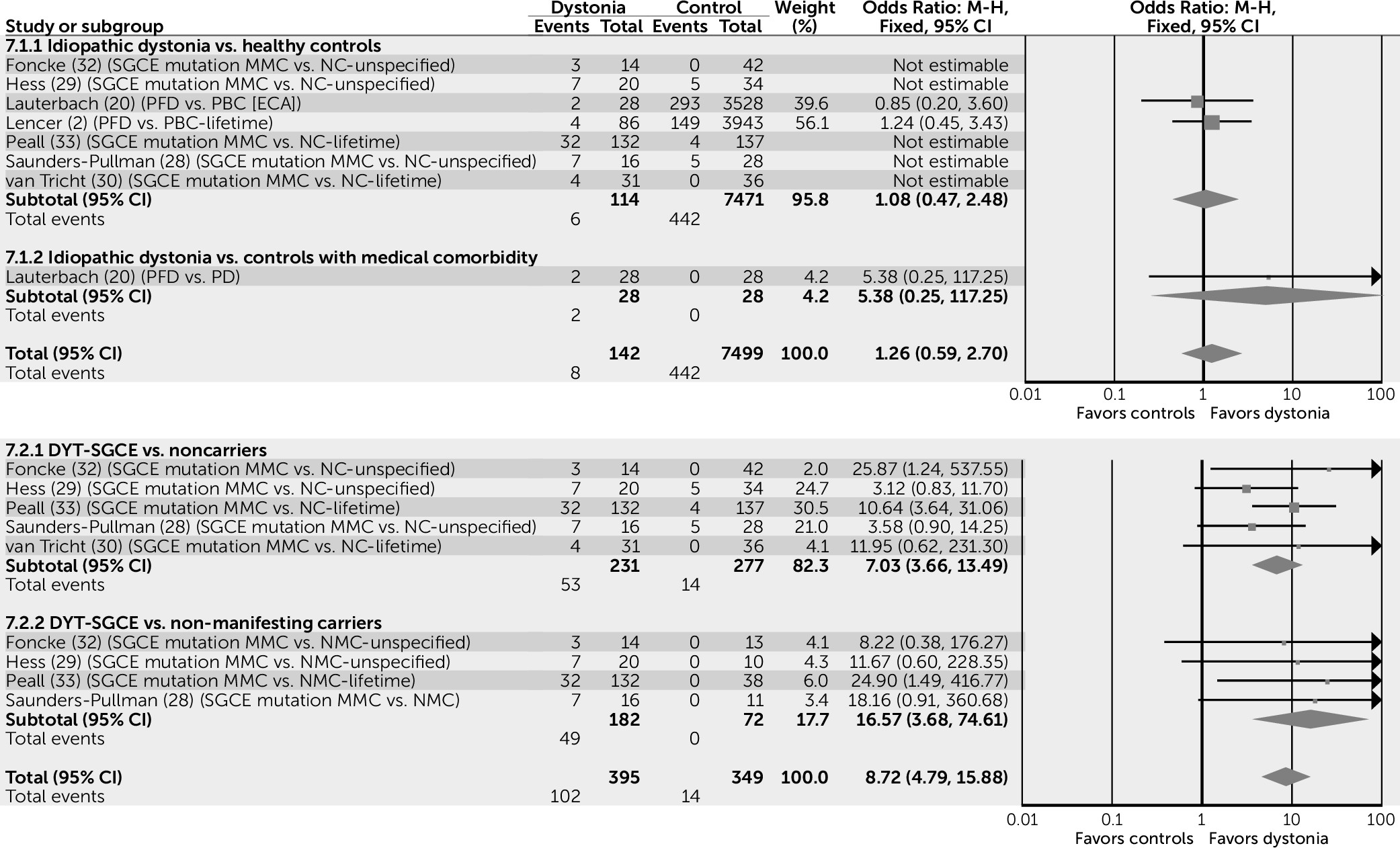

No differences were noted in the risk of alcohol dependence between subjects with idiopathic dystonia and control subjects (odds ratio=1.2, 95% CI=0.59–2.70). Conversely, data pertaining to DYT-SGCE suggest that MMCs have nine times the risk of developing alcohol dependence compared with both NC and NMC control subjects (odds ratio=8.72, 95% CI=4.79–15.88) (

Figure 5), suggesting that this association is likely to be due to the palliative effects of alcohol on motor symptoms rather than a direct effect of the SGCE gene.

Assessment of Quality and Limitations

These findings should be considered in conjunction with a number of limitations relating to the evidence from which they are drawn. As idiopathic and inherited forms of dystonia are rare, many of the studies not only reported on small numbers of sequentially sampled cases but also analyzed multiple types of primary dystonia in the same patient cohort. This has limited the ability of this review to examine the psychiatric associations of each individual condition and has led to subsequent subgroup analysis of results.

Because this study is a systematic review, the limitations pertaining to the overall effect estimates calculated and displayed in the forest plots need to be considered. These results were obtained using simple pooling of available data to provide an overall visual summary of results (

Figures 2–

5). This form of analysis can yield spurious findings, as data are combined irrespective of weighting for differences in study design, statistical models, and heterogeneity of study populations. Findings are limited by both small sample sizes and the limitations of publication bias, as smaller studies with negative findings are generally less likely to have been published and included in this review.

As only one study included analysis of subjects aged below 18 years of age, results cannot be generalized to pediatric populations (

31). Furthermore, developed countries are overrepresented; only one study was completed on a population sampled from an upper-middle income country, Brazil (

15). This is relevant, as the wealth of a nation has implications for the provision of mental health services and therefore the recognition and treatment of psychiatric illness (

37).

Generally, study subjects were sampled from single locations; only two studies recruited from multiple centers (

31,

33). This approach increased the risk of sampling bias by reducing the likelihood that cases were representative of their cohort population. For example, nine studies recruited from subpopulations in tertiary centers, which may have introduced selection bias (specifically, Berkson’s bias). However, the direction of this bias on the characteristics of the case population is unclear. It could be argued that tertiary patients are more likely to experience severe and disabling dystonia necessitating specialist intervention. Conversely, those with severe signs might be less able to travel to distant centers and therefore may have been underrepresented. The restrictions of each type of recruitment site (care registers, support groups, movement disorder outpatient clinics, botulinum toxin clinics, and inpatient units) should also be considered when interpreting results. For example, sampling dystonia support groups may have introduced membership bias, as subjects with higher levels of subjective distress and psychopathology might be more likely to seek support through membership. On the other hand, using botulinum toxin clinics as a site for recruitment may have falsely lowered the point prevalence of psychiatric illness; this treatment not only temporarily reduces associated pain and disfigurement but may also have additional effects on motor and psychiatric signs through a reduction in cortical somatosensory activity (

12,

15).

To control for these confounding factors, matching between groups is essential. Despite this, only 17 of the studies provided data on the most basic variables of age (adequately matched, N=11) and gender (adequately matched, N=3). Unfortunately, as most studies made no attempt to match groups for disability or disfigurement, the effect size contributed by the secondary nonspecific effects of having a chronic illness on the prevalence rates of mental illness are less clear.

Unfortunately, there are no validated psychiatric assessment tools for use in subjects with dystonia. To ensure the objective and standardized assessment of psychopathology, studies were required to use a structured psychiatric interview technique based on DSM or the International Classification of Diseases classification systems (

38). The most commonly used diagnostic assessments were the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM (SCID), used in 12 studies (

2,

12–

14,

16–

19,

30,

32,

33,

36,); the CIDI, used in eight studies (

2,

12,

26–

29,

33,

36); Mini International Neuropsychiatric Interview–Plus, used in five studies (

11,

15,

30,

31,

33); and the Diagnostic Interview Schedule, used in two studies (

18,

20). A number of studies also used a combination of assessor and self-rated psychiatric scales, including the brief self-reported Symptom Checklist–90–R, designed to broadly assess psychopathology (

11–

13,

18,

19,

39); the Beck Depression Inventory (

14,

15,

20,

32,

40) and Montgomery Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (

30–

32,

41) to assess depression; and the Beck Anxiety Inventory (

30,

32,

42), the Social Phobia Scale (

12,

18,

43), and the Yale-Brown Obsessive Compulsive Scale (

11,

13–

15,

30–

32,

36,

44) to assess anxiety and OCD. Significantly higher scores were noted among dystonia cases compared with control subjects for scales measuring depression (

14,

30–

32,

36), anxiety (

30,

32), social phobia (

12) and OCD (

11,

19,

31) (specifically relating to increased compulsions involving control, cleaning, and ordering [

19]).

Standardized assessments are advocated as the gold standard for psychiatric diagnostic interviewing (

45) and have previously been described as the cornerstone of evidence-based assessment (

46). These assessments have been reviewed extensively with regard to their degree of efficacy and reliability in obtaining psycho-diagnostic information and can be easily deployed by clinically inexperienced assessors (

45).

Although there are many benefits to their use, the potential biases introduced through the use of these categorical systems are worthy of mention. The goal of psychiatric interviewing is to translate an individual’s subjective lived experience and objective observable appearance into an insightful, actionable format that informs diagnostic classification and guides treatment decisions. The structured interview predefines what counts as important information by employing a format that involves asking the individual a series of set questions in sequence and rating their response, in order to determine the diagnosis. The lack of conversational flow and contextual flexibility may mean that important subtleties in an individual’s presentation are missed or misinterpreted. Building on the notion of Gestalt, oversimplification of psychopathology can lead to diagnostic inaccuracy, as the whole is often so much more than the sum of its parts (

45). More specifically, the structured interviews discussed in this article are not specific to dystonia and therefore may have missed important subtleties and subthreshold phenomena in the complex psychopathology of subjects, which may be key to understanding the differences in presentation between cases and control subjects. There may also be a degree of selection bias, particularly in relation to control subjects; for example, the small numbers of NMCs may not be representative of the group as a whole. The effects of these biases may be further compounded by the decision of some studies to use potentially clinically inexperienced assessors, including trained interviewers (

12,

18,

28,

36), telephone interviewers (

26,

27), and research assistants (

32).

Although this article is able to offer information on the prevalence of current and lifetime psychiatric diagnoses in patients of any age with idiopathic and inherited (monogenic) isolated or combined forms of dystonia, the methods employed in the research to date do not yield the information required to describe differences in the characteristics of psychiatric presentation between case and control populations. This would be an interesting and valuable area to explore in future research, perhaps through the use of more detailed psychiatric assessments involving a phenomenologically oriented, semi-structured interview with a conversational flow completed by a reliability-trained psychiatrist with a broad base of clinical experience (

45). As data collected on lifetime psychiatric symptomatology are prone to recall bias, this approach could be combined with a review of medical records to substantiate and support patient interviews.