Jean Lhermitte (1877–1959), a renowned neurologist and a psychiatrist from the Paris school, was one of the pioneers of behavioral neurology and of the neuropsychiatric interface (

1,

2). An important part of his work was devoted to hallucinations, about which he published an insightful book in 1951 (

3). Here, the focus is specifically on his works concerning hallucinations in their relation to dreaming and sleep. Lhermitte had been interested in sleep and its disorders, particularly narcolepsy and its accompanying symptoms (

4,

5), since the 1910s. In 1922, he was the first author to describe a syndrome of complex hallucinations following vascular damage to the midbrain (

6), which is still known as peduncular hallucinosis. From this seminal observation, Lhermitte put forward the hypothesis of a dissociation between components of sleep. Subsequently, he published other peduncular hallucinosis cases and remained constant in his interpretation all his life, disputing with some of his contemporaries. In spite of its limitations linked to the knowledge and means of the time, his work remains of great interest for the accuracy of its clinical descriptions and for his pathophysiological hypotheses, which were in many ways innovative. The books written by Lhermitte are well known, but his numerous articles are scattered over many publications. I systematically searched for all articles having Lhermitte as author or coauthor between 1910 and 1955, in

Revue Neurologique (Paris) and other medical French journals available online, mainly on the websites of the Bibliothèque Interuniversitaire Santé de Paris (biusante.parisdescartes.fr/histoire/medica/periodiques.php), the Bibliothèque Nationale de France (data.bnf.fr and gallica.bnf.fr), and the Bibliothèque Henri Ey of the Centre Hospitalier Saint-Anne (ghu-paris.fr/fr/bibliotheque-henri-ey). Other articles written by Lhermitte or contemporary authors that he cited in his work were also collected.

PEDUNCULAR HALLUCINOSIS: THE SEMINAL 1922 ARTICLE AND FOLLOWING OBSERVATIONS

Recent articles have summarized the history of peduncular hallucinosis (

12–

14). My aim is to analyze more precisely the emergence of this concept in the context of Lhermitte’s time, and then, in the next sections, to integrate peduncular hallucinosis into Lhermitte’s more general theory on the relationship between dreams and hallucinations, and to compare it with contemporary data.

The first observation of peduncular hallucinosis was reported by Lhermitte in 1922 to the Neurological Society of Paris under the title “Syndrome de la calotte du pédoncule cerebral. Les troubles psycho-sensoriels dans les lesions du mésencéphale” (“Syndrome of the peduncular cap [tegmentum]). Psycho-sensory disorders following mesencephalic lesions”) (

6). The patient was a 75-year-old woman. She initially had headache and vomiting, and within 2 weeks developed left paralysis of the abducens nerve, then of the oculomotor nerve, and on the right side facial paralysis, a Babinski sign, and kinetic cerebellar syndrome. CSF cell count and albumin concentration were normal. The picture mostly corresponded to Claude’s syndrome (

15) with additional pyramidal signs, and suggested involvement of the midbrain tegmentum. Damage to the left abducens nerve, without lateral gaze palsy, is unusual in this setting and could have been due to compression by a vertebrobasilar dolichoectasia (

16). Two weeks after completion of the somatic neurological disorders, as depicted by Lhermitte, “the patient spontaneously told us that during the day and especially at nightfall, she sees various animals walking around on the floor of the ward. There are cats, and hens slightly strange in appearance, their dilated pupils possessing a strange luster. In order to verify the reality of these perceptions, the patient tried to touch these animals. She told us that her contact with them resembles that of real animals, but as soon as she touched them, they slowly disappeared through the floor.” The patient “does not think that these are true perceptions, since, when questioned, none of the patients in the same hospital room had experienced them.” In addition, “sleep seems to be strongly disturbed and insomnia at night is associated with some sleepiness during the afternoon.” Three weeks after they began, “the visions are no longer of animals, but of human beings decked out in bizarre and tattered outfits, or children playing with dolls. The patient sees them in the beds of her neighbors.” Finally, insight weakens: “These images are so vivid, she tells us, that they can only correspond to reality,” but “no delusional ideas accompany these visual hallucinations.” In his comments Lhermitte, referring again to Camus (

11), stated that “it was not extravagant” to wonder if the mental disorders were related to the peduncular lesion. He insisted on the “striking similarity” between the almost exclusively visual sensory phenomena experienced by the patient and dreams, leading to the statement that hallucinosis was the expression of a dream in a half-asleep subject. Finally, based on his own previous work (

7) and that of other authors, Lhermitte concluded that the visual hallucinosis resulted from a “disturbance of the sleep function,” a condition that was “the equivalent of narcolepsy” and was related to the mesencephalic lesion.

In 1924, Ludo van Bogaert (1897–1989), the renowned neurologist and pathologist from Antwerp, Belgium, made the first clinico-anatomical observation of what he was the first to call “hallucinose pédonculaire” (peduncular hallucinosis) (

17). The patient, a woman aged 59, had a neurological picture close to Claude’s syndrome, with visual hallucinations, mainly zooptic: “From the very first evening, she saw a dog’s head on her pillow, and the opposite wall frequently bore a picture of a horse on a pink background. . . . On one occasion, she reported the presence of green snakes in her bed for a whole day. She touched them, pushing them away from the bed. They were rough against her hand. . . . None of these hallucinations provoked an emotional reaction in the patient; she shows no surprise . . . and is absolutely convinced of the reality of the animals she sees.” There were also dyschromatopsia and episodes of psychomotor agitation, independent of the hallucinations. A few years later, van Bogaert published additional clinical and autopsy data (

18). During the 14 months of follow-up, the patient still experienced “hallucinatory outbursts.” The lesion was “a focal peduncular softening by a syphilitic arteritis of the retromamillary pedicle,” extending to the superior colliculus and the pulvinar. This patient, unlike Lhermitte’s, did not have sleep disorders, leading van Bogaert to argue that “the release of the imaginative automatism can be dissociated from the hypnic state.” He thus diverged from Lhermitte’s interpretation and, referring to the conceptions of the psychiatrist and philosopher Pierre Quercy (

19), he stated that “the essential disorder is a momentary weakening of the self which disrupts the function of reality.”

However, for his entire life, Lhermitte remained convinced that peduncular hallucinosis made it possible to approach “the physiological basis of the dream” (

20). Following his 1922 article, he published nine other cases of peduncular hallucinosis or similar syndromes that strengthened his conviction. They are summarized in

Table 1, together with the first observation and two other historical cases. The next observation (

21) was that of a 70-year-old woman who suddenly fell into a “deep sleep,” with bilateral ophthalmoplegia suggestive of bilateral damage to the oculomotor nerves, bilateral pyramidal syndrome, and cerebellar syndrome. When the patient came out of her “lethargy,” she had in the evening “multiple, colorful visions” of animals or people “moving silently.” Sometimes “she thinks she is at the theatre, attending a variety of performances.” These phenomena did not evoke an emotional response. They were associated with memory impairment for recent events and confabulations. The picture retrospectively suggests a bilateral paramedian mesencephalic and thalamic infarction (

22).

A new observation, published with Gabrielle Lévy (1886–1935), differed from the others (

23). A 60-year-old man, suffering from long-standing tabes dorsalis, went into a coma after a suicide attempt with hypnotics. On waking, he had a crossed syndrome suggestive of mesencephalic damage (

Table 1). For a month, at nightfall, the subject experienced visual hallucinations, which were at first dreamlike: “He thought his room had been transformed into a railway or subway carriage.” Soon after, “since this carriage was in more or less close connection with an aeroplane service . . . he arrived on a platform overlooking a marvelous landscape resembling that of Arabia. A plane descended from the sky and landed on the platform. He climbed aboard. . . . Then he flew over wonderful landscapes for a few moments.” After a few days, the hallucinatory phenomena changed in nature. In the evening, “the walls of the room, the various objects that furnished it, come to life under the astonished gaze of the patient. Two pairs of trousers hung in front of him and a coat rack in the room become two bustling women.” Even the bare wall of his room became animated and lively: “Workers come to nail down tapestries, a modern kind of tapestry, but this tapestry becomes animated in its turn. Characters move around, curtsy to each other, make themselves understood.” The images are colorful and silent, they “are not unpleasant,” and the subject “realizes that he is the plaything of an illusion.” About 3 weeks after its onset, the hallucinosis decreased, with a few visions remaining before sleep: “heads that look at him strangely” on a wall outside. After 1 month, the hallucinatory phenomena subsided. The patient died of a pneumopathy, and a new article provided anatomical findings (

24). There were no macroscopic lesions, while histological examination showed “alterations of the peduncular cap (midbrain tegmentum) with metachromatic degeneration associated with an alteration of the ventral nucleus of the third nerve and of the median and intermediate nuclei.” Without excessive conviction, the authors linked these lesions with the drug intoxication. For Professor Françoise Gray (personal communication), the description is compatible with an ischemic lesion dating back several weeks, and leads to the hypothesis of low cerebral blood flow at the time of the intoxication with hypnotics, possibly in arteries with stenotic lesions (atheroma? syphilitic arteritis?).

In 1931, Lhermitte and Gabrielle Lévy (

25) published the observation of an elderly patient who 5 years earlier (

26) had suffered a “slight stroke” followed by a “pronation spasm of the right arm” (probably dystonia) and sensory disturbances in this limb. Since this accident, the patient “very frequently [saw], at night, a man’s head appear on the wall facing her bed.” The head was “black and grey on a white background . . . the figure [was] very recognizable.” To make it disappear, the patient focused on another object. The vision was rather pleasant, and insight was retained. The patient also suffered from nightmares with screaming. Lhermitte believed that the lesion was located in the subthalamic area and related this observation to those previously published of peduncular hallucinosis. The lesion more likely involved the posterolateral region of the thalamus (

27,

28). The same authors published a similar case soon after (

29).

An observation by Georges de Morsier (1894–1982), a Swiss neuropsychiatrist, generated new discussions (

30). A 54-year-old woman suddenly developed Claude’s syndrome; 18 months later, she reported predominantly evening visions of colorful figures or animals, appearing for a few seconds. The images unfold “like in the cinema.” They “always come from the left and move from left to right until they reach the median line where they disappear.” The visions did not give an impression of reality and did not cause anxiety. They occurred irregularly and could stop for several weeks. Sleep was mostly undisturbed. Although visual fields and visual acuity were normal, de Morsier postulated the existence of a unilateral, retrochiasmatic lesion of the visual pathways. He did not propose any mechanism to explain these hallucinations limited to a visual hemifield, in the absence of detectable damage to the visual field, unlike the hallucinations in a hemianopic field after an ischemic stroke first described in the United States by Seguin in 1886 (

31) and in France by Lamy in 1895 (

32). No anatomical study was available in this case. Lhermitte stated, at the end of this presentation, that lesions of the optic tract or lateral geniculate bodies never cause hallucinations, which is not certain, even if observations are rare (

33). More generally, Lhermitte constantly rejected the hypothesis that an alteration of the visual pathways could contribute to peduncular hallucinosis.

Subsequently, Lhermitte and his collaborators published four more cases of peduncular hallucinosis (

34–

36), one of them secondary to a peduncular hemorrhage (

36), and one observation of hallucinations following a vascular lesion situated in the pons and medulla (

37) (

Table 1). In addition, five cases presumed to be due to hemorrhage of the peduncular tegmentum were summarized in a review article (

38).

PEDUNCULAR HALLUCINOSIS AS A “DISSOCIATION OF THE HYPNIC STATE”

In 1932, Lhermitte summarized his conceptions of peduncular hallucinosis in an article published in

L’Encéphale (

39). He gave a definition of hallucinosis, in line with that proposed by his contemporaries: “hallucinatory states which do not lead to true delusions”; and of peduncular hallucinosis: “hallucinatory manifestations which appear and develop in patients suffering from lesions limited to the mesodiencephalon, i.e., to the ventral region of the third ventricle and the peduncular cap [tegmentum].” Lhermitte underlined the common features of his cases: “visions of mobile, colorful, and silent animals or animated characters,” occurring in the evening, in the absence of surprise and anxiety, without delusions. Insight, on the other hand, differed from one patient to another; patients might “become caught up in the hallucination when it occurs with crudeness, vividity and naturalness.” Hallucinosis was associated with sleep disturbances. Lhermitte’s views on pathogenesis can be summarized as follows: There is a regulating center for wakefulness and sleep in the mesodiencephalon; sleep has a negative feature, the “suspension of consciousness,” and a positive feature, dreaming; lesions causing sleep alteration can also modify dream activity; and in peduncular hallucinosis observations, there are sleep disorders and visions with “the same attributes as those of dreaming” and “obvious similarities with hypnagogic images.” Lhermitte concluded that a patient with peduncular hallucinosis “is therefore a dreamer awake or insufficiently asleep, a subject whose profoundly disturbed hypnic function has been dissociated by the whim of an anatomical disorganization.” A dissociation of dream mechanisms, however, was not sufficient to explain peduncular hallucinosis. Lhermitte attempted to reconcile his conception with that of van Bogaert, according to whom hallucination was due to “a weakening of the sense of reality . . . causing images and representations to take on an abnormal brilliance.” For Lhermitte, “to sleep and to dream is to slacken one’s attention to reality . . . and to scatter before a drowsy consciousness the images and representations that constitute the capricious and incessantly moving weft of the dream” (

23).

In a 1934 review (

40), Lhermitte added a few recent cases, including that of Garcin and Renard (

41) associating multiple cranial nerve damage, sleep disorders, and visual hallucinations, all transient phenomena attributed to a viral infection affecting the brainstem. The message was that, whatever the cause (vascular, toxic, infectious), the mesodiencephalic region was altered and responsible for the hallucinosis. However, one observation contradicted this assertion (

37): A 33-year-old man was suddenly affected by a crossed syndrome (

Table 1) presumed to be hemorrhagic and suggestive of a lesion located in the medulla and the pons. Besides somatic neurological symptoms, the patient had, on the one hand, the impression that his legs occupied a position far above the bed plane, and, on the other, visual evening and night hallucinations, in the form of characters moving silently. The first symptom was a postural illusion, similar to phantom limbs, probably related to sensory deafferentation, a symptom rarely reported following brainstem lesions (

42). Besides, the hallucinosis suggested that a lesion of the medulla or the pons could generate a syndrome similar to peduncular hallucinosis, as already reported by Stenvers (

43) in a patient with a pons tuberculoma who had, in addition to focal signs, visual and auditory hallucinations. Lhermitte, reluctant to admit that a pontine lesion could induce a peduncular hallucinosis, evoked a “disruption in the equilibrium of the organo-vegetative system,” referring to Raoul Mourgue, author of an “organo-vegetative” theory of hallucinations that hardly survived its author (

44). In a new review, Lhermitte (

45) commented on the dreamlike and hypnagogic phenomena of narcolepsy and the hallucinations associated with sleep paralysis. All these phenomena had in common that they were the positive side of a hypnic function disorder. In his 1951 book (

3), Lhermitte devoted 20 pages to “hallucinosis of peduncular origin.” He added some new brief observations, which widened the phenomenological picture: ocular paralysis could be missing; auditory hallucinations, including verbal ones, could occur; and lesions could involve the floor of the third ventricle or the pons. Lhermitte remained true to the concept of a dissociation of the hypnic state and specified that the causal focal lesion only generated hallucinations because it “activated extremely complicated mechanisms, which took place throughout the entire extent of the brain, and especially in the cerebral cortex.” Lhermitte thus refuted the objections of Mourgue, who reproached him for confusing “the anatomical localization with that of the functional syndrome” (

44).

CONCLUSIONS

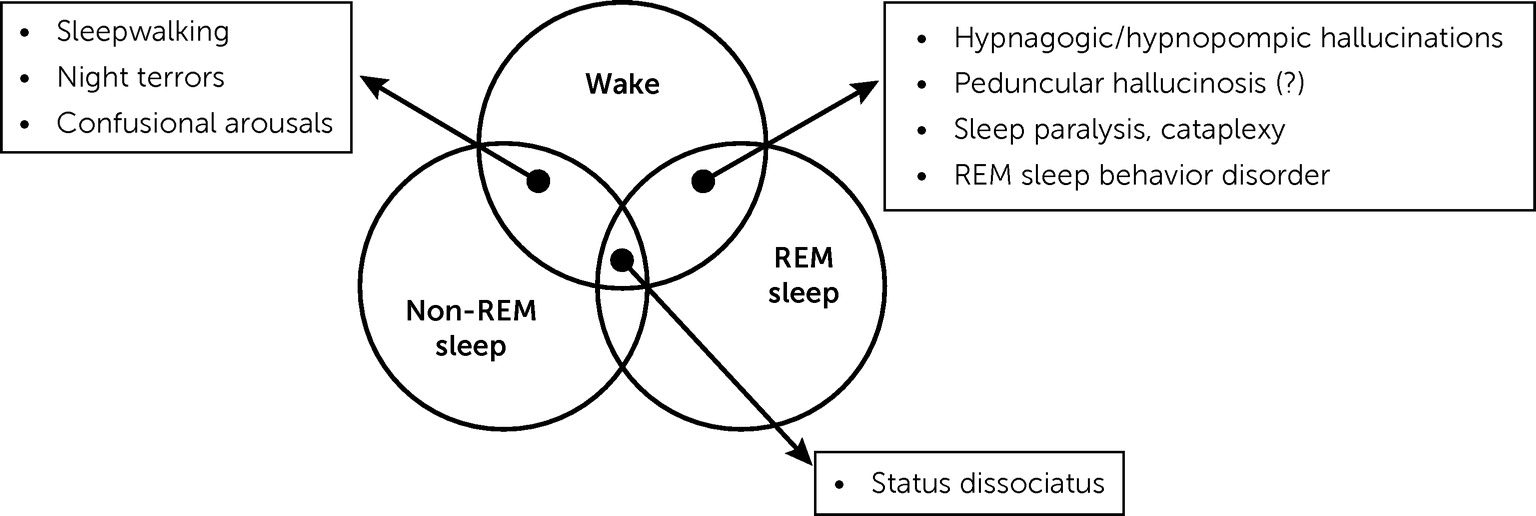

Jean Lhermitte, in his 1922 article and following works, proposed or anticipated three innovative concepts that still have implications for contemporary clinicians and researchers. The first issue is that a focal lesion, located in the upper part of the brainstem, may cause hallucinations in the visual modality and possibly in others. At a time when psychic phenomena and higher cognitive functions were primarily ascribed to the cortex, Lhermitte claimed that “thought requires, for its normal functioning, the integrity not only of the cortex but of the underlying centers” (

6). His model of a limited lesion acting through complex mechanisms and ultimately involving the cortex, possibly inspired by John Hughlings Jackson (1835–1911) (

89), remains valid (

75). This view also prefigures contemporary advances taking into account the lesion-induced functional alterations in anatomically intact, connected regions, including in the field of hallucinations (

47). Secondly, Lhermitte postulated that peduncular hallucinosis was the result of a dissociation of the mechanisms of dream and waking states, the lesion disrupting the anatomy and connections of a center regulating wakefulness and sleep. The definition of peduncular hallucinosis has since been extended to cases involving a thalamic lesion, but the syndrome described by Lhermitte, although rare, remains accepted. His pathophysiological assumptions were limited by a lack of knowledge, at his time, of the complex and still partially obscure mechanisms regulating wakefulness, the different stages of sleep, and dreaming. The attractive but overly simplistic idea that peduncular hallucinosis is due to a mere intrusion of dreaming in a waking subject has not been confirmed, and the precise mechanisms involved in peduncular hallucinosis remain mysterious. However, discussions on the relationship between dreams and hallucinations are still going on (

70,

90). Thirdly, Lhermitte identified that a dissociation of states, as conceptualized nowadays, underpinned several phenomena related to sleep, such as hypnagogic hallucinations, cataplexy, sleep paralysis, confusional arousals, and somnambulism.

According to MacDonald Critchley, Jean Lhermitte “was the

beau idéal of a neuropsychiatrist” (

91). With the description of the peduncular hallucinosis and the discussion of its mechanisms, Lhermitte initiated a broader reflection on hallucinations, which, almost a century later, perfectly illustrates the close relationship and the necessary dialogue between neurology and psychiatry.

Recent studies have examined the relationship between hallucinations and dreams (

92,

93), as well as hallucinations in narcolepsy (

94–

96), building on Jean Lhermitte’s model.