Case Presentation

A 58-year-old left-handed woman with 12 years of education was referred for further evaluation and management of progressive cognitive dysfunction. A diagnosis of Alzheimer disease (AD) was suspected by the referring neurologist on the basis of an MRI demonstrating mild temporal atrophy, EEG demonstrating bitemporal slowing, positive cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) AD biomarkers, and apolipoprotein E (APOE) ε4, ε4 genotype. The patient had a 4-year history of progressive cognitive symptoms. Early symptoms included difficulties recalling recent events and information, sustaining attention, and learning new tasks. She was repeatedly disoriented to the time of day; for example, she would get dressed for the day in the middle of the night. She had difficulties finding words and expressing her thoughts, with a decline in the richness of her vocabulary.

An initial clinical interview revealed that the patient had become increasingly withdrawn from family and friends. Over the year prior to evaluation at our center, she developed an array of neuropsychiatric symptoms, including depression, anxiety, and recurrent, well-formed visual hallucinations of unfamiliar people in her house. She did not feel threatened or bothered by these people and retained insight that others could not see them.

The patient had last worked as an administrative assistant approximately 3 years prior to evaluation at our center and was unable to obtain new work because of her cognitive symptoms. More recently, her husband assumed responsibility for overseeing administration of her medications and for shopping and most meal planning and preparation. She continued to drive intermittently and to prepare breakfast independently. She remained independent in basic activities of daily living, including showering, dressing, eating, toileting, and mobility.

The patient’s mother and father lived into their 70s and 80s, respectively, and died from cancer, without any history of progressive cognitive impairment or dementia. A maternal aunt who died in her 70s had progressive cognitive impairment starting in her late 50s.

Questions: What are the diagnostic considerations based on the history? Is this presentation suggestive of AD? Would additional history be helpful?

Insidious onset and gradual progression of cognitive symptoms over the course of 4 years raises concern for a neurodegenerative disorder. In this type of scenario, it is useful to derive a three-tiered diagnostic formulation comprising neurodegenerative clinical syndrome, severity, and suspected underlying neuropathology (

1,

2). Setting aside the reports of the neuroimaging, CSF, and genetic results, aspects of the patient’s history suggesting changes in episodic memory, attention, executive function, and word retrieval could suggest a multidomain, amnesic syndrome as frequently occurs in the context of AD neuropathology. However, recurrent, well-formed visual hallucinations are very uncommon with isolated AD neuropathology and suggestive of contributions from Lewy body disease (LBD) neuropathology, as occurs in association with syndromic dementia with Lewy bodies (DLB), Parkinson disease (PD), or PD with dementia (PDD) (

3). It would be useful to know whether this patient has additional history indicating other core clinical features of a DLB syndrome, including fluctuating cognition with pronounced variations in attention and alertness; REM sleep behavior disorder (RBD), suggested by dream enactment behaviors; and motor symptoms potentially reflecting parkinsonism (

4,

5). Instruments such as the Mayo Fluctuations Scale and the Queen Square Visual Hallucination Inventory provide useful questions for assessing the range of fluctuation phenomena and minor and major visual hallucinations and illusions possible in DLB (

6,

7) (

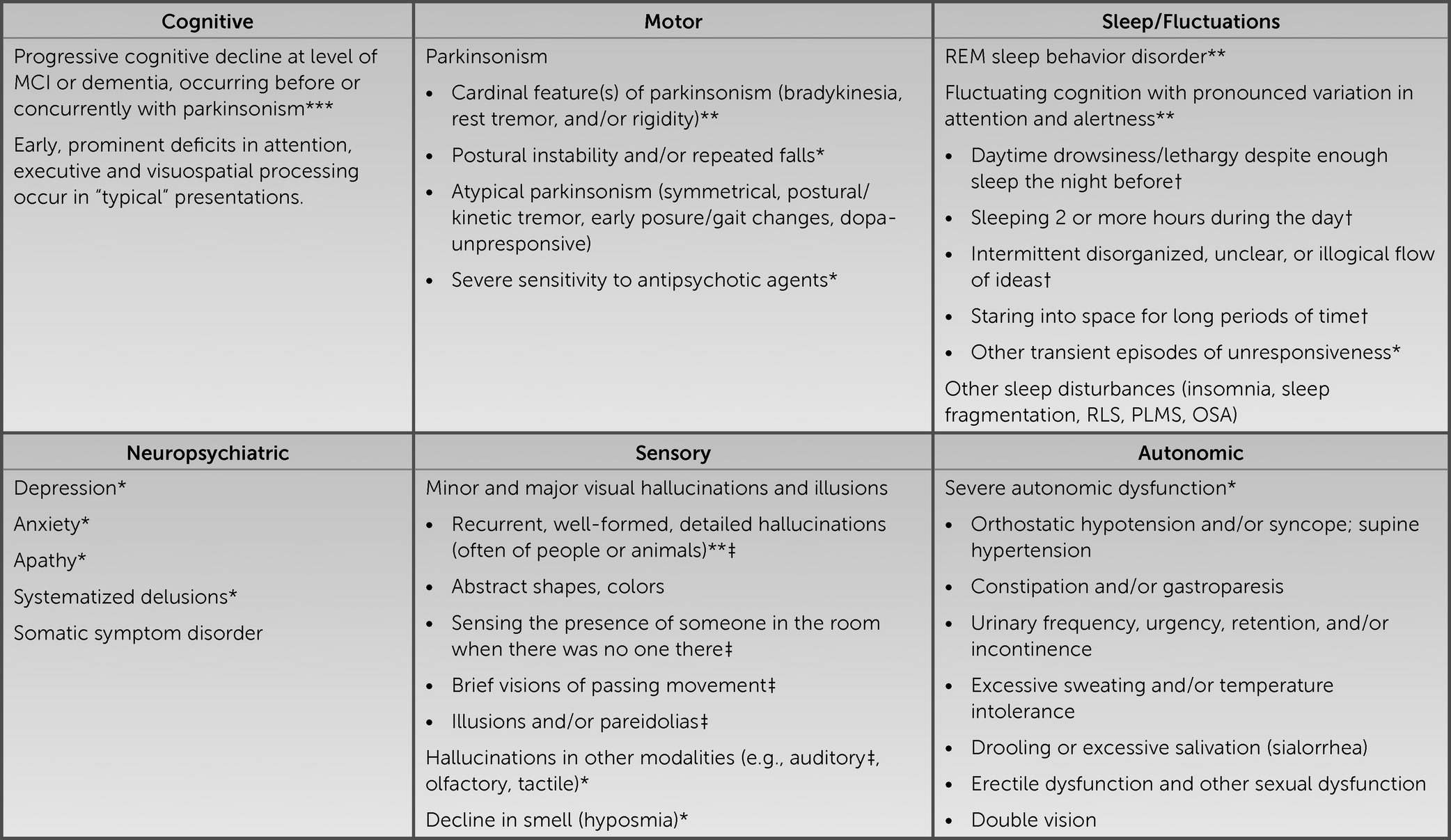

Figure 1). Additional supportive clinical features would include various other symptoms in the domains of motor function, sleep, neuropsychiatric function, sensory processing, and autonomic function (

8–

11).

Additional history revealed that the patient’s husband observed her to have periods of being in a “trance-like” state, as well as drowsiness and an increased tendency to sleep in the daytime. She was noted to have recurrent episodes of “acting out her nightmares,” at times kicking and screaming, dating back to the onset of her cognitive symptoms. Her walking had slowed, and her voice had become softer. She was slower and less coordinated when using her hands, her handwriting became smaller, and she developed intermittent tremors of her hands and arms when using them. She experienced constipation with increasing frequency and severity.

Question: What are the aims of the cognitive and neurological examinations in this context?

In the context of a history highly suggestive of DLB, one can increase diagnostic confidence by establishing a suggestive neuropsychological profile or by confirming features of parkinsonism on examination. DLB is frequently associated with early impairments in attention, executive function, and visuospatial processing (

12–

14). To assess parkinsonism, it is useful to gain familiarity with elements of the motor examination section of the Movement Disorders Society–sponsored revision of the Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale, including assessment of speech, facial expression, rigidity, finger tapping, hand movements (opening and closing), hand pronation-supination, toe tapping, leg agility (foot stomping), arising from chair, gait, posture, postural stability, global spontaneity of movement, and presence or absence of postural, kinetic, or rest tremors of the hands (

15). PD syndrome is more likely to be associated with typical parkinsonism, i.e., early asymmetrical “pill-rolling” resting tremor, limb bradykinesia and rigidity that tend to be responsive to levodopa, and minimal to no early postural instability. Although typical parkinsonism can occur in DLB, atypical features occur more frequently, including the absence of resting tremor, the presence of postural-kinetic or mixed tremor, less prominent and more symmetrical early bradykinesia and rigidity, more prominent early postural instability, and reduced responsiveness to levodopa (

16–

18). Despite these distinctions, it is noteworthy that all symptomatic features of DLB can occur in PDD and vice versa, with the arbitrary distinguishing feature between the syndromes being whether cognitive dysfunction develops prior to or concurrently with parkinsonism (as in DLB and as was observed in this patient) or following parkinsonism (as in PDD) (

4). Considering PD, PDD, and DLB as syndromes under the umbrella term “Lewy body disorders” allows for variability in presentations along a spectrum, from individuals with predominantly motor symptoms to those with predominantly cognitive symptoms (

19). These disorders all share a common neuropathological substrate that is indistinguishable at the microscopic level but appears to differ in terms of topographical distribution and spreading patterns (

20).

This patient’s mental status examination revealed grossly apparent psychomotor slowing. She scored a 24/30 on the Mini-Mental State Examination, missing 2 points on orientation to year and day of the week, 2 points on the three-item delayed word recall test (obtaining both with a category cue), and 1 point for poor pentagon copy (

21). She was given a subset of the Hooper Visual Organization Test, on which she correctly identified seven of 13 objects represented in line drawings as puzzle pieces (suggesting a moderate level of visuospatial impairment) (

22).

On elemental neurological examination, the patient had hypomimia, saccadic intrusions during smooth-pursuit eye movements, and slow, hypophonic speech. Strength was full in the proximal and distal muscles of the arms and legs. There was a postural-kinetic tremor of both hands, mild left-greater-than-right bradykinesia apparent on finger tapping and hand movements, and mild left-greater-than-right cogwheel rigidity in the arms. She rose from a chair easily, without the use of her arms. Her gait was mildly slow, with a narrow base and left-greater-than-right reduced arm swing. There was no retropulsion on pull testing.

Taken together, these examination results provided additional support for a DLB syndrome. The cognitive examination, though limited and nonspecific, provided some evidence of slow processing speed, impaired memory (at least at the level of retrieval), and visuospatial dysfunction. The motor examination provided unequivocal evidence of parkinsonism, some features that were typical, such as asymmetrical limb bradykinesia and cogwheel rigidity, and other features that were atypical, such as postural-kinetic tremor of the hands.

Question: What initial tests and studies are indicated?

Structural neuroimaging of the brain, preferably with MRI, is a recommended component in the initial evaluation of suspected dementia (

23,

24). When specific neurodegenerative causes of dementia are under consideration, imaging serves at least two purposes. First, it helps to assess for evidence of alternative (nondegenerative) conditions that might account for or contribute to symptoms. Second, it helps to assess for atrophy in a topographical distribution suggestive of a neurodegenerative syndrome and/or neuropathology, which can be useful in cases with possible underlying AD or frontotemporal lobar degeneration (FTLD) neuropathological changes (

25). In a case such as this one, with features suggesting a DLB syndrome, imaging can be useful to assess for alternative causes of parkinsonism, such as vascular disease. While relative preservation of medial temporal lobe (MTL) regions on structural neuroimaging represents a supportive biomarker for DLB, evidence of MTL atrophy does not preclude a diagnosis of DLB, particularly considering that a DLB clinical syndrome may be associated with mixed LBD and AD neuropathological changes (

4,

26).

In cases of suspected DLB with profound fluctuations in attention, focal dyscognitive seizures are included in the differential diagnosis. Here, an EEG can be useful to distinguish between epileptiform activity (which is consistent with seizures) and prominent posterior slow-wave activity with periodic fluctuations in the pre-alpha/theta range (which is another supportive biomarker for DLB) (

4).

Otherwise, a standard laboratory evaluation including comprehensive metabolic profile (CMP), vitamin B12 level, TSH, and complete blood counts (CBC) would add value in screening for potential contributing factors.

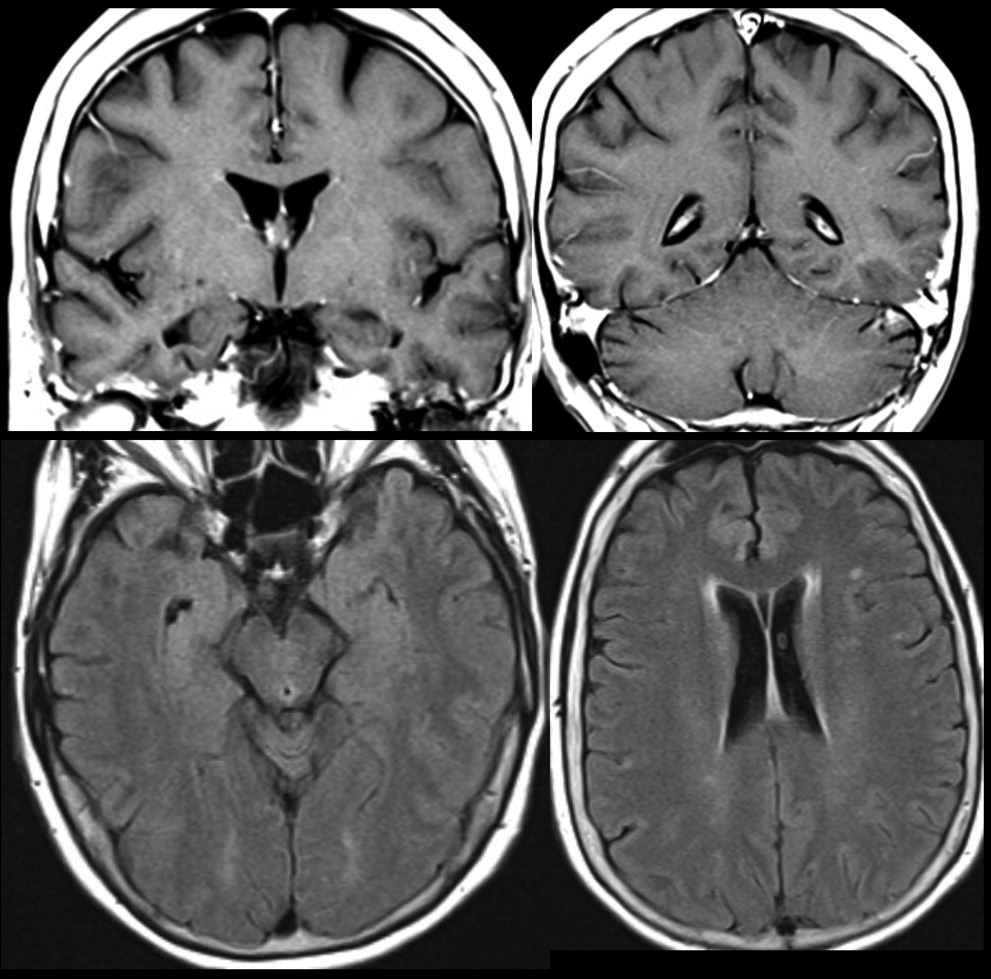

This patient’s MRI, completed approximately 9 months prior to referral, demonstrated a mild degree of T2 hyperintense signal changes in the periventricular, subcortical and juxtacortical white matter. There was no diffusion restriction, evidence of atrophy, or abnormal enhancement (

Figure 2). A routine EEG demonstrated “mild intermittent bitemporal irregular slowing with no focal or generalized epileptiform features.” There were no pertinent lab result abnormalities.

Question: Are additional tests and studies indicated?

Given the presence of all four core clinical features, multiple supportive clinical features (constipation, anxiety, and depression), and a supportive biomarker (relative preservation of MTL structures on MRI) for DLB in this case, there was no strong rationale to obtain additional data to confirm the diagnosis. In cases in which a diagnosis of DLB is less clear, consideration may be given to obtaining what have been designated indicative biomarkers, including dopamine transporter SPECT or PET imaging for evidence of reduced uptake in the basal ganglia,

123iodine-metaiodobenzylguanidine (MIBG) myocardial scintigraphy for evidence of low uptake, or polysomnography for confirmation of REM sleep without atonia (

4).

At the time of the patient’s initial presentation, when Lewy body features were less apparent, the referring neurologist had a higher level of suspicion for an amnesic syndrome with underlying AD neuropathology than for a DLB syndrome with underlying LBD or mixed LBD-AD neuropathology. Concern for AD in a patient with mild cognitive impairment or dementia at a young age at onset (<65 years) represents an appropriate indication for obtaining CSF beta-amyloid-42 (Aβ42), total tau, and phosphorylated tau levels, as occurred in this case (

27). Molecular biomarkers of AD neuropathology can also provide value in etiologically mixed presentations in which AD might contribute to an illness in which other factors are also suspected, e.g., LBD, vascular neuropathology, or both (

28). Indeed, CSF evidence of underlying AD in patients with DLB has been associated with more rapid cognitive decline (

29).

CSF results were suggestive of AD, because Aβ42 was low at 437.2 pg/ml, total tau was elevated at 639.7 pg/ml, the Aβ42-to-total tau index was low at 0.44, and phosphorylated tau was elevated at 83 pg/ml.

Question: Is genetic testing indicated?

Experts do not recommend routine clinical genetic testing for patients with DLB or patients with AD who lack a family history suggesting autosomal-dominant inheritance (

4,

30). In cases in which a familial autosomal-dominant neurodegenerative disorder is suggested by the clinical presentation and family history, consideration may be given for referral to a genetics counselor and potential testing for mutations in selected genes. Families with an autosomal-dominant disorder typically contain at least three affected individuals in two or more generations, with two of the individuals being first-degree relatives of the third individual, and the disorder usually involves an early age at onset. Although the presence of the

APOE ε4 allele is a risk factor for both AD and DLB, its presence is neither sensitive to nor specific for either condition, and

APOE genotyping is not recommended as part of a diagnostic evaluation (

30,

31). Although the utility of

APOE genotyping for purposes other than diagnosis, such as clinical prognostication, has not been studied as extensively, the presence of an

APOE ε4 allele in patients with DLB has been associated with greater severity of LBD neuropathology, independent of AD neuropathology, and shorter mean time between onset of cognitive symptoms and death (

32,

33).

Prior to referral, this patient tested negative for mutations in

PSEN1, PSEN2, and

APP. She was found to be a homozygous carrier of the

APOE ε4 allele.

Question: What would be an appropriate diagnostic formulation?

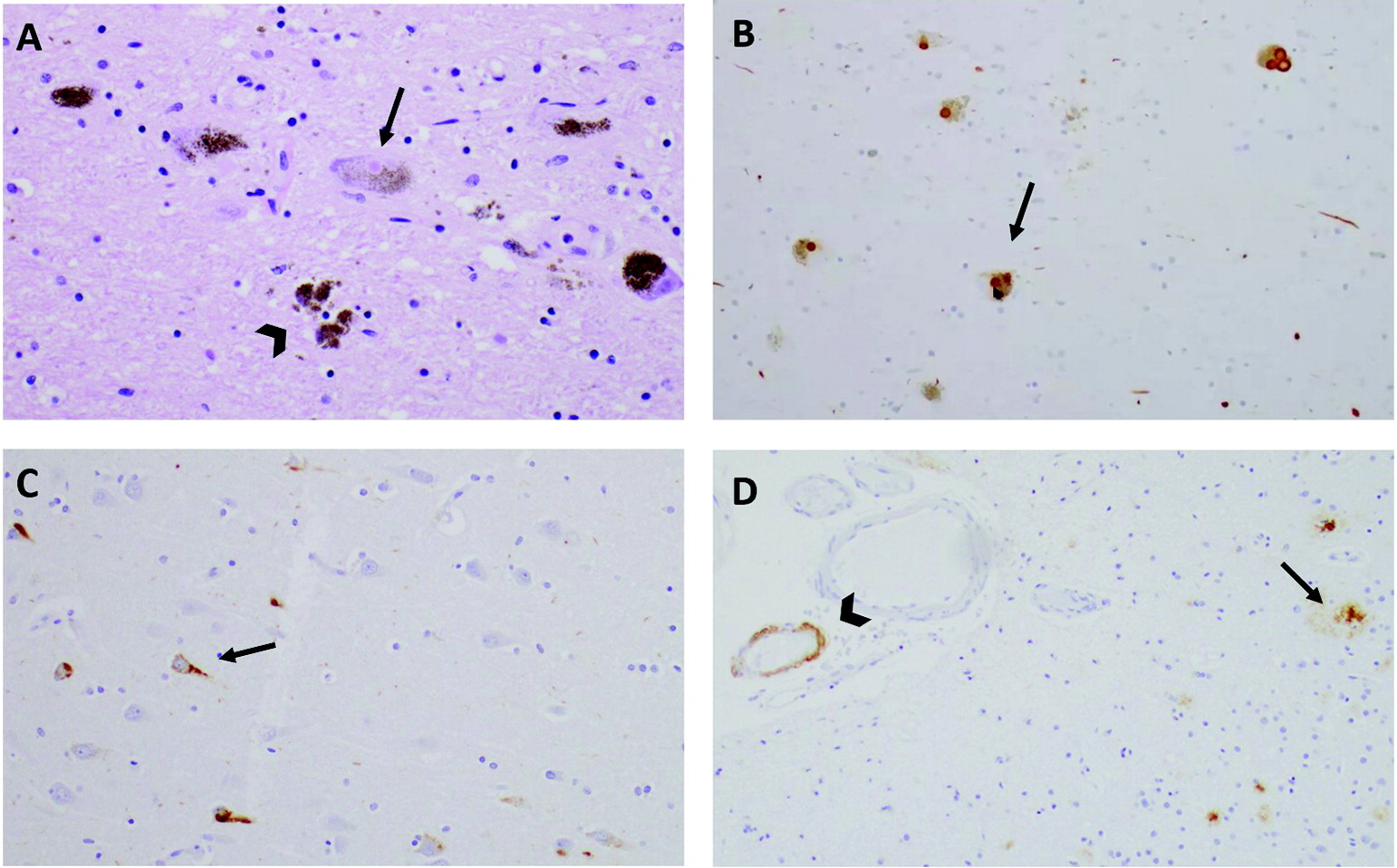

As reviewed above, ample evidence supported a syndromic diagnosis of DLB. The patient’s loss of independence in selected instrumental activities of daily living supported staging at a level of mild dementia. Regarding suspected neuropathology, several factors supported a prediction of mixed LBD and AD neuropathology. A clinical diagnosis of DLB has greater than 95% specificity for pathological confirmation of diffuse neocortical Lewy bodies (

34). Clinical and neuropathological correlation studies likewise suggest that 60%–70% of cases with a clinical diagnosis of DLB have intermediate- or high-level AD copathology (

26).

Question: What are reasonable therapeutic considerations?

Because many different types of symptoms can arise in the context of DLB, it is helpful to take a systematic approach to therapeutic planning by reviewing the nature and severity of disease impact on cognition, neuropsychiatric health (e.g., mood, anxiety, and psychosis), sleep, motor function, and autonomic function. Considering the impact of symptoms within each of these domains on the patient’s quality of life and ability to carry out intended activities helps to identify and prioritize targets for pharmacological intervention (

35–

50) (

Table 1). Additional research is needed to establish stronger evidence for many symptomatic treatments (

35,

45,

51). Importantly, nontrivial symptomatic benefits can frequently be obtained from discontinuing and avoiding nonessential medications with anticholinergic or dopamine receptor–blocking properties. Neuroleptic medications in particular should be avoided, given their propensity to precipitate severe, potentially life-threatening reactions (

52).

At the time of referral, the symptoms with the greatest impact on this patient’s level of function and quality of life were those involving her cognitive function, mood, anxiety, and sleep. Although meaningful in terms of diagnosis, the patient’s formed visual hallucinations and motor symptoms were not causing significant distress at presentation and therefore did not warrant pharmacological treatment. Evidence from randomized controlled trials and meta-analyses supports the efficacy of cholinesterase inhibitors for cognitive and potentially for neuropsychiatric symptoms (including anxiety, delusions, and hallucinations) in DLB patients (

53,

54). Rivastigmine and donepezil have been studied more extensively than galantamine, and the results with rivastigmine and donepezil have been comparable (

35,

36). Either would be a reasonable choice for this patient, with monitoring for sleep-related and gastrointestinal side effects (

Table 1).

No systematic studies of antidepressants or anxiolytics have been conducted for treatment of depression or anxiety among patients with DLB (

55). Selected selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and serotonin-norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors, such as sertraline, escitalopram, and venlafaxine, may provide benefit, although they should be used carefully (i.e., “start low and go slow”) given their potential to cause or exacerbate gastrointestinal and sleep-related problems in this population. Patients with treatment-refractory depression may benefit from repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation or electroconvulsive therapy (

56,

57).

In cases of RBD involving frequent, disruptive, or injurious behaviors, melatonin is often well tolerated and effective in reducing dream enactment behaviors (

58). Standard practice is to start at 3 mg or 5 mg and to titrate weekly in increments of 3 mg or 5 mg as needed, up to 15 mg to 18 mg nightly (

59). Clonazepam may be used as a second-line treatment in severe cases; however, the potential to exacerbate cognitive dysfunction and obstructive sleep apnea should be noted.

This patient was started on transdermal rivastigmine, titrated from 4.6 mg daily to 9.5 mg daily after 1 month, and there were notable reductions in her visual hallucinations and fluctuations in attention and alertness. She did not tolerate a further increase in dose to 13.3 mg daily on account of insomnia. She derived a moderate benefit from melatonin 6 mg nightly, with respect to reducing dream enactment behaviors. Sertraline, started approximately 6 months later, was effective in reducing her anxiety at a dose of 50 mg daily. Insomnia, initially nonresponsive to medications, including trazodone and mirtazapine, improved later with an increase in the dose of melatonin to 15 mg nightly.

The patient’s clinical status deteriorated steadily despite these early symptomatic improvements. Two years after her initial behavioral neurology evaluation and 6 years after onset of symptoms, she required full-time supervision and assistance to pick out clothes and dress, and she appeared frequently frustrated and agitated. Her husband derived benefit from visits with a social worker in the behavioral neurology and neuropsychiatry unit, who provided disease-specific counseling and education, assistance with completion of medical and financial legal documents, and recommendations on care arrangements and reviewed behavioral and environment-based strategies for managing neuropsychiatric symptoms. In-home services and support from additional family members allowed her husband to continue to work on a part-time basis.

In subsequent months, the patient’s course was complicated by intermittent problems, such as dehydration, constipation, and emotional lability, and by chronic problems, including the loss of communicative abilities and mobility. She was transitioned to a memory care unit and later to skilled nursing. She died at age 63, 5 years after the initial behavioral neurology presentation and 9 years after the onset of symptoms.