A 55-year-old right-handed woman presented with a 3-year history of cognitive changes. Early symptoms included mild forgetfulness—for example, forgetting where she left her purse or failing to remember to retrieve a take-out order her family placed—and word-finding difficulties. Problems with depth perception affected her ability to back her car out of the driveway. When descending stairs, she had to locate her feet visually in order to place them correctly, such that when she carried her dog and her view was obscured, she had difficulty managing this activity. She struggled to execute relatively simple tasks, such as inserting a plug into an outlet. She lost the ability to type on a keyboard, despite being able to move her fingers quickly. Her symptoms worsened progressively for 3 years, over which time she developed a sad mood and anxiety. She was laid off from work as a nurse administrator. Her family members assumed responsibility for paying her bills, and she ceased driving.

Her past medical history included high blood pressure, Hashimoto’s thyroiditis with thyroid peroxidase antibodies, remote history of migraine, and anxiety. Medications included mirtazapine, levothyroxine, calcium, and vitamin D. She had no history of smoking, drinking alcohol, or recreational drug use. There was no known family history of neurologic diseases.

What Are Diagnostic Considerations Based on the History? How Might a Clinical Examination Help to Narrow the Differential Diagnosis?

Insidious onset and gradual progression of cognitive symptoms over the course of several years raise concern for a neurodegenerative disorder. It is helpful to consider whether or not the presentation fits with a recognized neurodegenerative clinical syndrome, a judgment based principally on familiarity with syndromes and pattern recognition. Onset of symptoms before age 65 should prompt consideration of syndromes in the spectrum of frontotemporal dementia (FTD) and atypical (nonamnesic) presentations of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) (

1,

2). This patient’s symptoms reflect relatively prominent early dysfunction in visual-spatial processing and body schema, as might be observed in posterior cortical atrophy (PCA), although the history also includes mention of forgetfulness and word-retrieval difficulties. A chief goal of the cognitive examination would be to survey major domains of cognition—attention, executive functioning, memory, language, visual-spatial functioning, and higher somatosensory and motor functioning—to determine whether any domains stand out as more prominently affected. In addition to screening for evidence of focal signs, a neurological examination in this context should assess for evidence of parkinsonism or motor neuron disease, which can coexist with cognitive changes in neurodegenerative presentations.

The patient’s young age and history of Hashimoto’s thyroiditis might also prompt consideration of Hashimoto’s encephalopathy (HE; also known as steroid-responsive encephalopathy), associated with autoimmune thyroiditis. This syndrome is most likely attributable to an autoimmune or inflammatory process affecting the central nervous system. The time course of HE is usually more subacute and rapidly progressive or relapsing-remitting, as opposed to the gradual progression over months to years observed in the present case (

3).

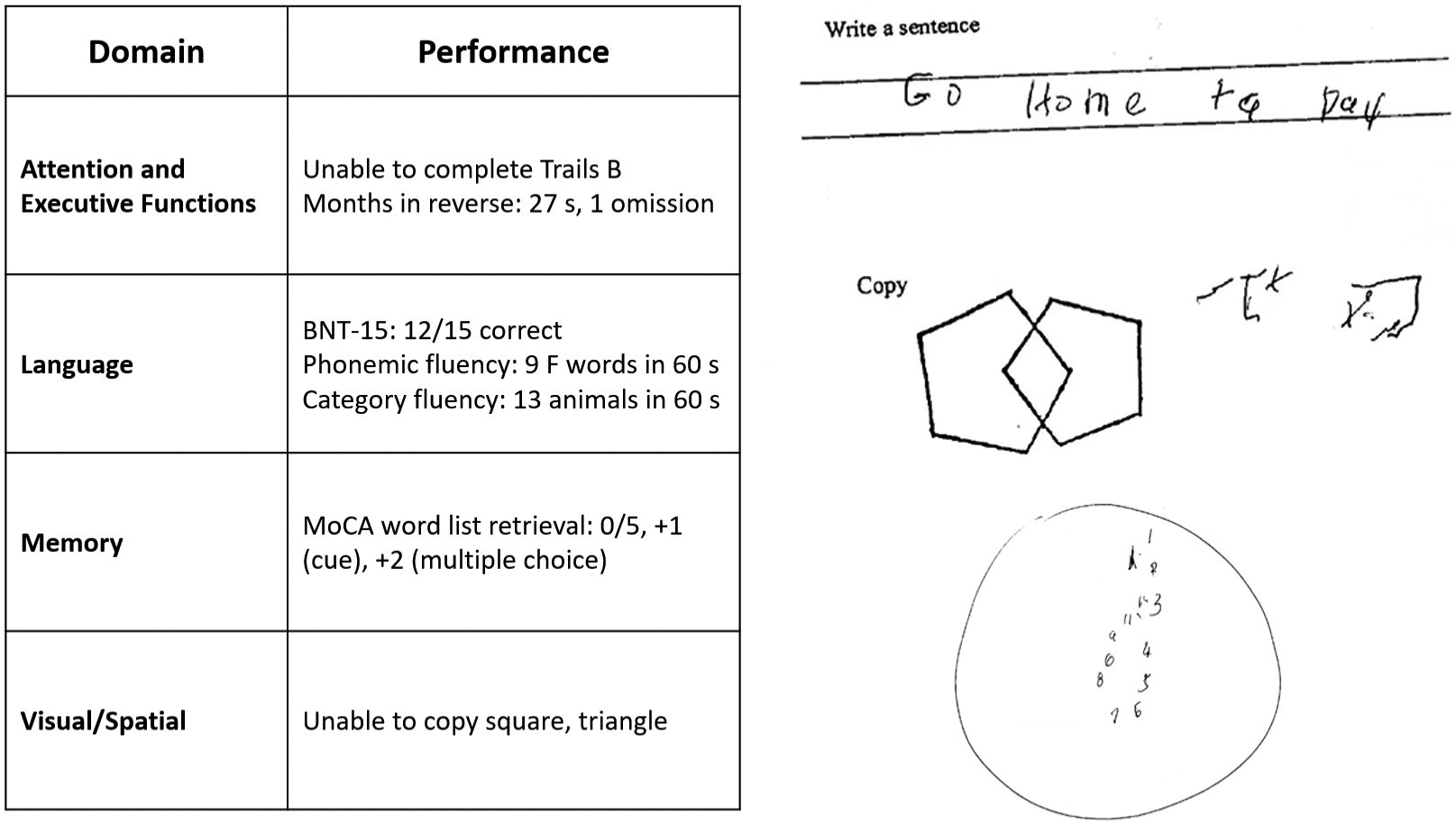

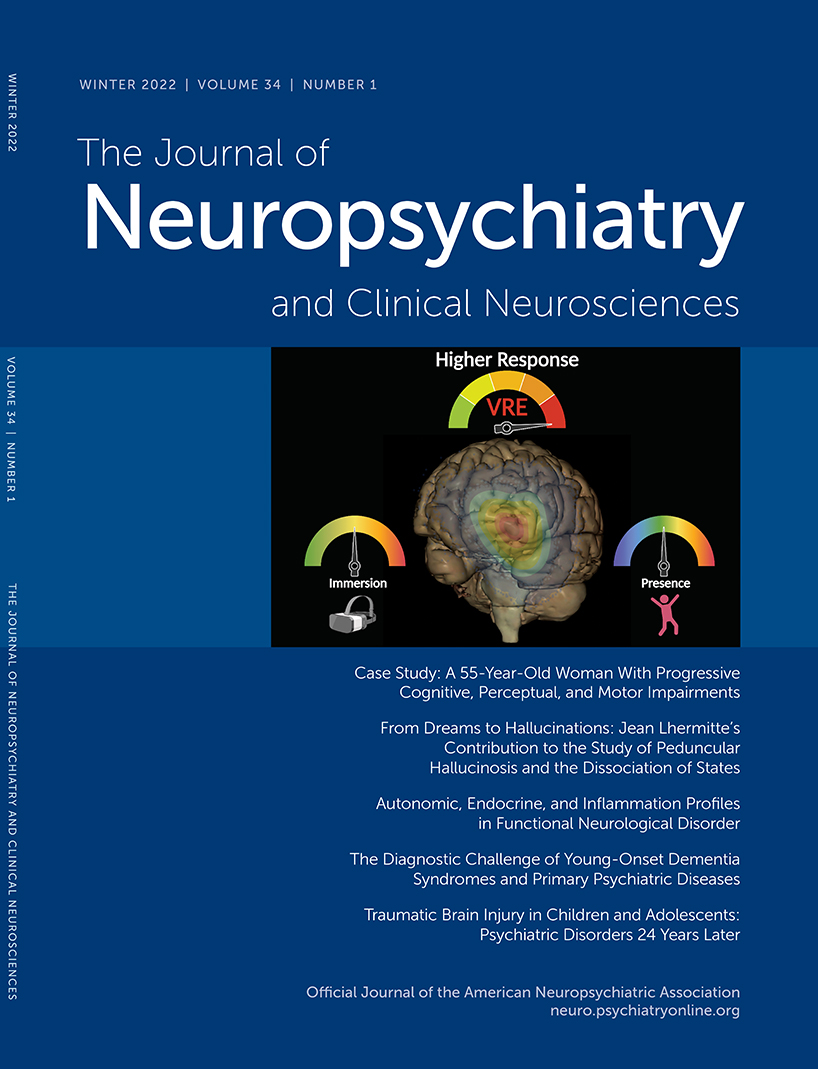

The patient’s mental status examination included the Montreal Cognitive Assessment (MoCA), a brief global screen of cognition (

4), on which she scored 12/30. There was evidence of dysfunction across multiple cognitive domains (

Figure 1). She was fully oriented to location, day, month, year, and exact date. When asked to describe a complex scene from a picture in a magazine, she had great difficulty doing so, focusing on different details but having trouble directing her saccades to pertinent visual information. She likewise had problems directing her gaze to specified objects in the room and problems reaching in front of her to touch target objects in either visual field. In terms of other symptoms of higher order motor and somatosensory functioning, she had difficulty demonstrating previously learned actions—for example, positioning her hand correctly to pantomime holding a brush and combing her hair. She was confused about which side of her body was the left and which was the right. She had difficulty with mental calculations, even relatively simple ones such as “18 minus 12.” In addition, she had problems writing a sentence in terms of both grammar and the appropriate spacing of words and letters on the page.

On elementary neurologic examination she had symmetrically brisk reflexes, with spread. She walked steadily with a narrow base, but when asked to pass through a doorway she had difficulty finding her way through it and bumped into the door jamb. Her elemental neurological examination was otherwise normal, including but not limited to brisk, full-amplitude vertical eye movements, normal visual fields, no evidence of peripheral neuropathy, and no parkinsonian signs such as slowness of movement, tremor, or rigidity.

How Does the Examination Contribute to Our Understanding of Diagnostic Considerations? What Additional Tests or Studies Are Indicated?

The most prominent early symptoms and signs localize predominantly to the parietal association cortex: The patient has impairments in visual construction, ability to judge spatial relationships, ability to synthesize component parts of a visual scene into a coherent whole (simultanagnosia or asimultagnosia), impaired visually guided reaching for objects (optic ataxia), and most likely impaired ability to shift her visual attention so as to direct saccades to targets in her field of view (oculomotor apraxia or ocular apraxia). The last three signs constitute Bálint syndrome, which localizes to disruption of dorsal visual networks (i.e., dorsal stream) with key nodes in the posterior parietal and prefrontal cortices bilaterally (

5). She has additional salient symptoms and signs suggesting left inferior parietal dysfunction, including ideomotor limb apraxia and elements of Gerstmann syndrome, which comprises dysgraphia, acalculia, left-right confusion, and finger agnosia (

6). Information was not included about whether she was explicitly examined for finger agnosia, but elements of her presentation suggested a more generalized disruption of body schema (i.e., her representation of the position and configuration of her body in space). Her less prominent impairment in lexical-semantic retrieval evidenced by impaired confrontation naming and category fluency likely localizes to the language network in the left hemisphere. Her impairments in attention and executive functions have less localizing value but would plausibly arise in the context of frontoparietal network dysfunction. At this point, it is unclear whether her impairment in episodic memory mostly reflects encoding and activation versus a rapid rate of forgetting (storage), as occurs in temporolimbic amnesia. Regardless, it does not appear to be the most salient feature of her presentation.

This localization, presenting with insidious onset and gradual progression, is characteristic of a PCA syndrome. If we apply consensus clinical diagnostic criteria proposed by a working group of experts, we find that our patient has many of the representative features of early disturbance of visual functions plus or minus other cognitive functions mediated by the posterior cerebral cortex (

Table 1) (

7). Some functions such as limb apraxia also occur in corticobasal syndrome (CBS), a clinical syndrome defined initially in association with corticobasal degeneration (CBD) neuropathology, a 4-repeat tauopathy characterized by achromatic ballooned neurons, neuropil threads, and astrocytic plaques. However, our patient lacks other suggestive features of CBS, including extrapyramidal motor dysfunction (e.g., limb rigidity, bradykinesia, dystonia), myoclonus, and alien limb phenomenon (

Table 1) (

8).

In addition to a standard laboratory work-up for cognitive impairment, it is important to determine whether imaging of the brain provides evidence of neurodegeneration in a topographical distribution consistent with the clinical presentation. A first step in most cases would be to obtain an MRI of the brain that includes a high-resolution T1-weighted MRI sequence to assess potential atrophy, a T2/fluid-attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) sequence to assess the burden of vascular disease and rule out less likely etiological considerations (e.g., infection, autoimmune-inflammatory, neoplasm), a diffusion-weighted sequence to rule out subacute infarcts and prion disease (more pertinent to subacute or rapidly progressive cases), and a T2*-gradient echo or susceptibility weighted sequence to examine for microhemorrhages and superficial siderosis.

A lumbar puncture would serve two purposes. First, it would allow for the assessment of inflammation that might occur in HE, as approximately 80% of cases have some abnormality of CSF (i.e., elevated protein, lymphocytic pleiocytosis, or oligoclonal bands) (

9). Second, in selected circumstances—particularly in cases with atypical nonamnesic clinical presentations or early-onset dementia in which AD is in the neuropathological differential diagnosis—we frequently pursue AD biomarkers of molecular neuropathology (

10,

11). This is most frequently accomplished with CSF analysis of amyloid-β-42, total tau, and phosphorylated tau levels. Amyloid positron emission tomography (PET) imaging, and most recently tau PET imaging, represent additional options that are approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration for clinical use. However, insurance often does not cover amyloid PET and currently does not reimburse tau PET imaging. [

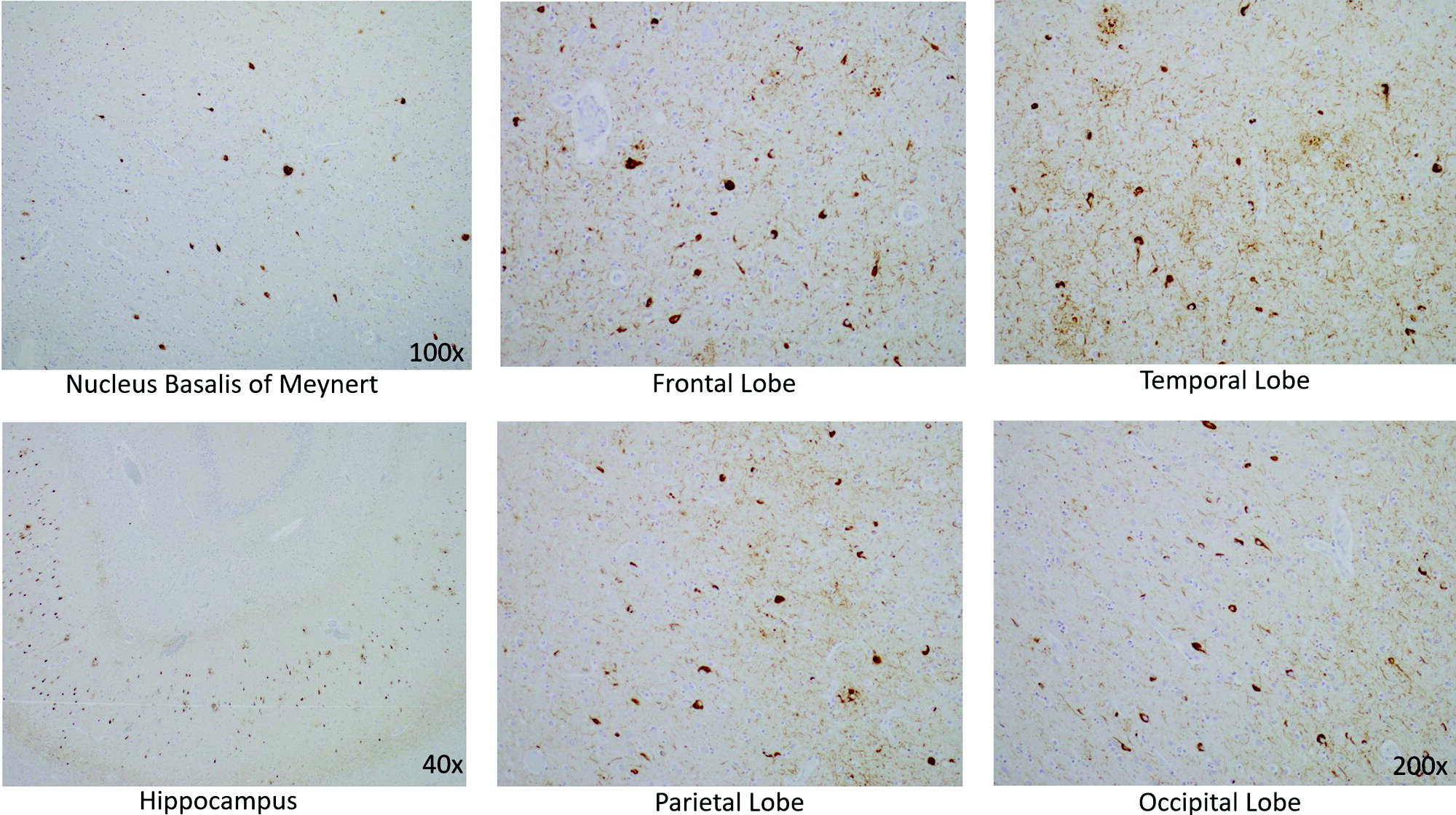

18]-F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) PET and perfusion single-photon emission computed tomography imaging may provide indirect evidence for AD neuropathology via a pattern of hypometabolism or hypoperfusion involving the temporoparietal and posterior cingulate regions, though without molecular specificity. Pertinent to this case, a syndromic diagnosis of PCA is most commonly associated with underlying AD neuropathology—that is, plaques containing amyloid-β and neurofibrillary tangles containing tau (

12–

15).

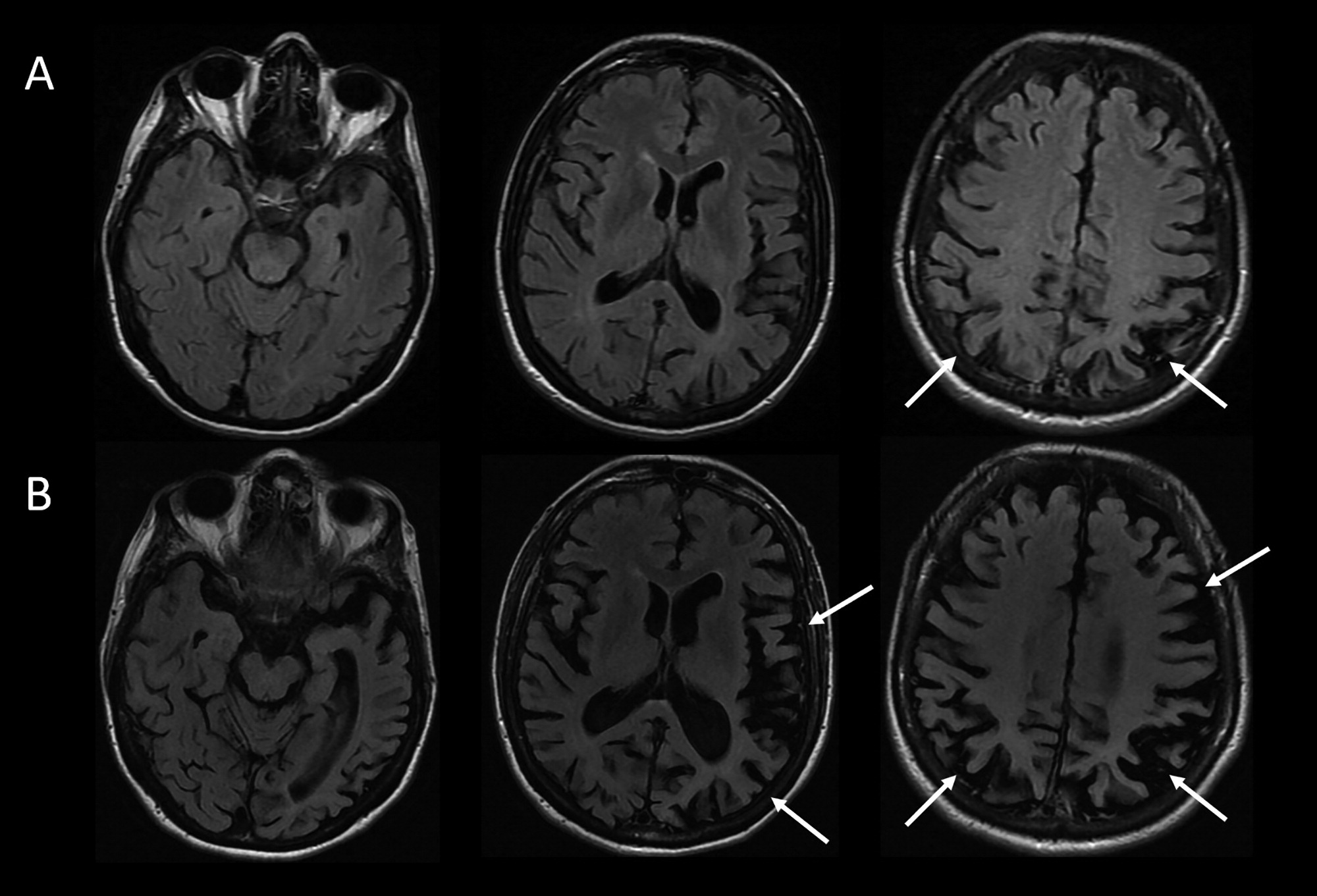

The patient underwent MRI, demonstrating a minimal burden of T

2/FLAIR hyperintensities and some degree of bilateral parietal volume loss with a left greater than right predominance (

Figure 2A). There was relatively minimal medial temporal volume loss. Her basic laboratory work-up, including thyroid function, vitamin B

12 level, and treponemal antibody, was normal. She underwent a lumbar puncture; CSF studies revealed normal cell counts, protein, and glucose levels and low amyloid-β-42 levels at 165.9 pg/ml [>500 pg/ml] and elevated total and phosphorylated tau levels at 1,553 pg/ml [<350 pg/ml] and 200.4 pg/ml [<61 pg/ml], respectively.

Considering This Additional Data, What Would Be an Appropriate Diagnostic Formulation?

For optimal clarity, we aim to provide a three-tiered approach to diagnosis comprising neurodegenerative clinical syndrome (e.g., primary amnesic, mixed amnesic and dysexecutive, primary progressive aphasia), level of severity (i.e., mild cognitive impairment; mild, moderate or severe dementia), and predicted underlying neuropathology (e.g., AD, Lewy body disease [LBD], frontotemporal lobar degeneration) (

16). This approach avoids problematic conflations that cause confusion, for example when people equate AD with memory loss or dementia, whereas AD most strictly describes the neuropathology of plaques and tangles, regardless of the patient’s clinical symptoms and severity. This framework is important because there is never an exclusive, one-to-one correspondence between syndromic and neuropathological diagnosis. Syndromes arise from neurodegeneration that starts focally and progresses along the anatomical lines of large-scale brain networks that can be defined on the basis of both structural and functional connectivity, a concept detailed in the network degeneration hypothesis (

17). It is important to note that neuropathologies defined on the basis of specific misfolded protein inclusions can target more than one large-scale network, and any given large-scale network can degenerate in association with more than one neuropathology.

The MRI results in this case support a syndromic diagnosis of PCA, with a posteriorly predominant pattern of atrophy. Given the patient’s loss of independent functioning in instrumental activities of daily living (ADLs), including driving and managing her finances, the patient would be characterized as having a dementia (also known as major neurocognitive disorder). The preservation of basic ADLs would suggest that the dementia was of mild severity. The CSF results provide supportive evidence for AD amyloid plaque and tau neurofibrillary tangle (NFT) neuropathology over other pathologies potentially associated with PCA syndrome (i.e., CBD, LBD, TDP-43 proteinopathy, and Jakob-Creutzfeldt disease) (

13,

14). The patient’s formulation would thus be best summarized as PCA at a level of mild dementia, likely associated with underlying AD neuropathology.

The patient’s symptoms progressed. One year after initial presentation, she had difficulty locating the buttons on her clothing or the food on her plate. Her word-finding difficulties worsened. Others observed stiffness of her right arm, a new symptom that was not present initially. She also had decreased ability using her right hand to hold everyday objects such as a comb, a brush, or a pen. On exam, she was noted to have rigidity of her right arm, impaired dexterity with her right hand for fine motor tasks, and a symmetrical tremor of the arms, apparent when holding objects or reaching. Her right hand would also intermittently assume a flexed, dystonic posture and would sometime move in complex ways without her having a sense of volitional control.

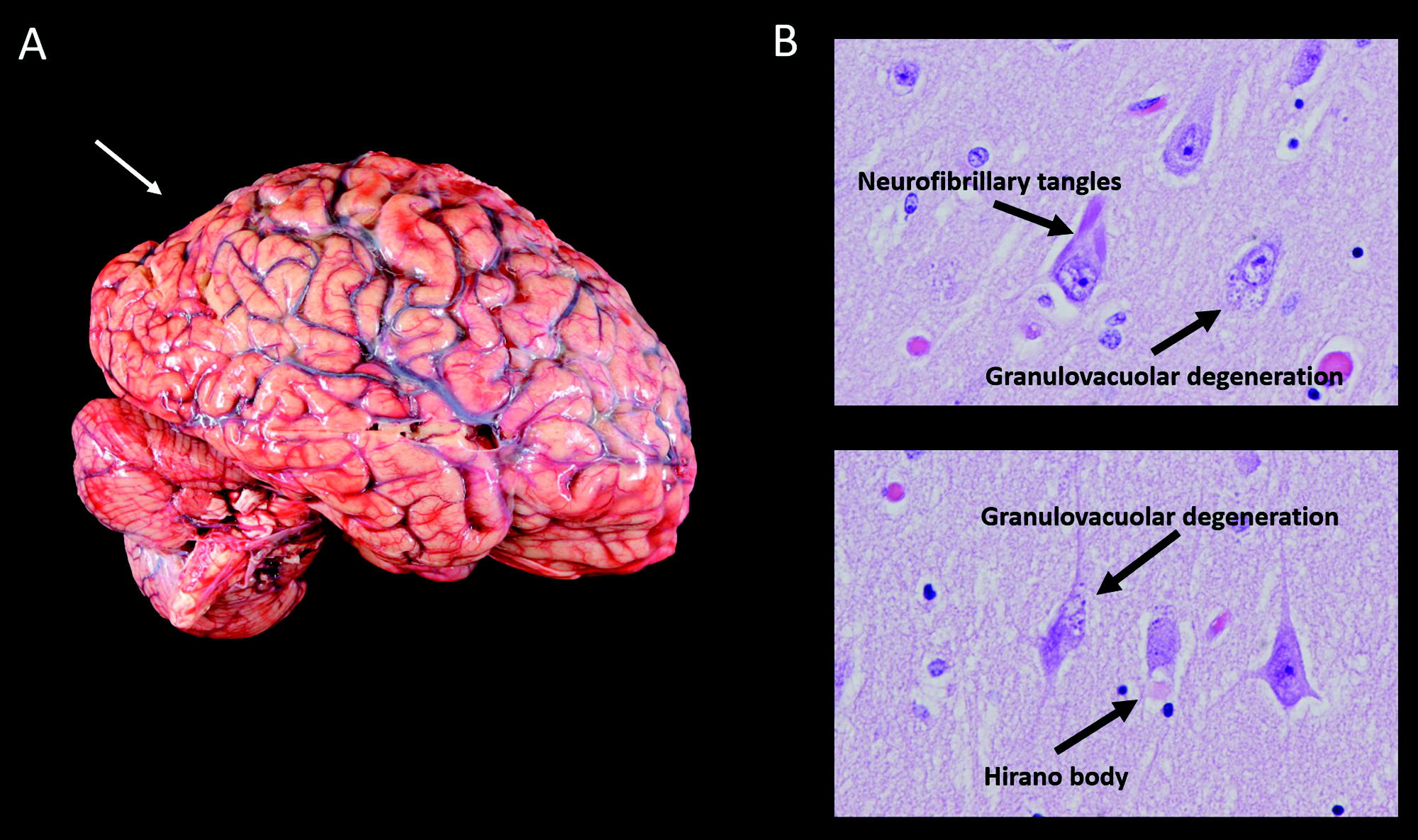

Four to 5 years after initial presentation, her functional status declined to the point where she was unable to feed, bathe, or dress herself. She was unable to follow simple instructions. She developed neuropsychiatric symptoms, including compulsive behaviors, anxiety, and apathy. Her right-sided motor symptoms progressed; she spent much of the time with her right arm flexed in abnormal postures or moving abnormally. She developed myoclonus of both arms. Her speech became slurred and monosyllabic. Her gait became less steady. She underwent a second MRI of the brain, demonstrating progressive bilateral atrophy involving the frontal and occipital lobes in addition to the parietal lobes and with more left > right asymmetry than was previously apparent (

Figure 2B). Over time, she exhibited increasing weight loss. She was enrolled in hospice and ultimately passed away 8 years from the onset of symptoms.

Does Information About the Longitudinal Course of Her Illness Alter the Formulation About the Most Likely Underlying Neuropathological Process?

This patient developed clinical features characteristic of corticobasal syndrome over the longitudinal course of her disease. With time, it became apparent that she had lost volitional control over her right arm (characteristic of an alien limb phenomenon), and she developed signs more suggestive of basal ganglionic involvement (i.e., limb rigidity and possible dystonia). This presentation highlights the frequent overlap between neurodegenerative clinical syndromes; any given person may have elements of more than one syndrome, especially later in the course of a disease. In many instances, symptomatic features that are less prominent at presentation but evolve and progress can provide clues regarding the underlying neuropathological diagnosis. For example, a patient with primary progressive apraxia of speech or nonfluent-agrammatic primary progressive aphasia could develop the motor features of a progressive supranuclear palsy (PSP) clinical syndrome (e.g., supranuclear gaze impairment, axial rigidity, postural instability), which would suggest underlying PSP neuropathology (4-repeat tauopathy characterized by globose neurofibrillary tangles, tufted astrocytes, and oligodendroglial coiled bodies).

If CSF biomarker data were not suggestive of AD, the secondary elements of CBS would substantially increase the likelihood of underlying CBD neuropathology presenting with a PCA syndrome and evolving to a mixed PCA-CBS. But the CSF amyloid and tau levels are unambiguously suggestive of AD (i.e., very low amyloid-β-42 and very high p-tau levels), the neuropathology of which accounts for not only a vast majority of PCA presentations but also roughly a quarter of cases presenting with CBS (

18,

19). Thus, underlying AD appears most likely.